Last month’s exploration of the history of enchantment began with a look at the other side of the equation—the disenchantment of the world mapped out by Max Weber—and then a survey of the ways that enchantment and disenchantment were understood by Ken Wilber, one of the modern thinkers who’s built a theory of history on Weber’s thesis. Wilber’s insistence that myth and magic belong to an outmoded stage of human development is far from unique to him, of course; it’s an attempt to give intellectual respectability to one of the widely held beliefs of our time.

Plenty of other serious thinkers have made the same sort of effort. The one I want to discuss this week was less interested in publicity than Ken Wilber, or possibly less adept at it. Despite his connections with one of the twentieth century’s most famous literary circles, he remains little known outside certain modern intellectual subcultures. That’s unfortunate, because Owen Barfield—close friend of C.S. Lewis and member of the Inklings, the group that counted Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Charles Williams as its leading luminaries—is a writer and thinker worth reading, reflecting on, and contending with.

While his writings are nothing like as voluminous as Wilber’s, they cover a comparable range of ideas, and I have no intention of trying to summarize his whole philosophy here. As I did with Wilber, I simply intend to discuss his understanding of the evolution of consciousness, the part of his philosophy that bears most directly on our theme. This is easier than it was with Wilber, because Barfield summed up his view of the subject crisply in a single, relatively short book, Saving The Appearances. It’s an impressive piece of work, not least because of its brevity; the average reader can finish it in an evening, but its ideas deserve the kind of attention and reflection that can occupy years of thought.

Like Wilber, Barfield argues that among modern Western people, at least, what I am calling enchantment is an outworn condition of consciousness that cannot and should not be brought back to life. Like Wilber, furthermore, he argues that our current state of consciousness, with its materialistic fixations, is a temporary phase that will be replaced, not by the previous state of enchantment, but by a higher state which will make room for a great many of the spiritual impulses that modern materialist thought brushed aside.

His map of this journey of consciousness is rather simpler than Wilber’s, however. The journey starts in a condition Barfield calls “original participation,” in which the human mind does not distinguish its own contents from its surroundings. In the state of original participation, there is no boundary between thoughts and things, mind and matter, and everything that is perceived by the senses is understood as having the same kind of inner life of experience and feeling that human beings have. Barfield’s summary is typically neat: “The essence of original participation is that there stands behind the phenomena, and on the other side of them from me, a represented which is of the same nature as me.”

If this sounds like the definition of enchantment I offered a month ago, there’s good reason for that; I modeled my definition on Barfield’s. He was talking about enchantment in the same terms I am, and he was alive to its spiritual dimensions in a way I’m not at all sure Wilber has ever been. The final sentence in his book, along these lines, offers another, even more precise definition: “the other name for original participation, in all its long-hidden, in all its diluted forms, in science, in art, and in religion, is after all—paganism.”

That last word all but gives away the show, of course. Barfield was a Christian—an exotic type of Christian, as he was an adherent of Rudolf Steiner’s quirky system of Christian occultism, but a Christian nonetheless. To him paganism could never be anything but an error of the past that the good people have now outgrown. The process by which it was outgrown, and the direction he thought that this process was destined to take in the future, was the entire subject of Saving the Appearances. Put another way, Barfield set out to take the classic Christian narrative of history from Eden to the New Jerusalem and make sense of it in philosophical terms.

That’s been tried many times, of course, but the way that he does this deserves respect. He starts by pointing out that modern science has utterly disproved the naive notion that what we perceive with our senses is what’s actually in front of us. Consider a rubber ball. Our senses tell us that it’s red, that it makes a squeaky noise when squeezed, and so on. What modern science has demonstrated is that these qualities—the red color, the squeaky noise, and the rest of it—are not part of the lattice of field-effects in raw spacetime that make up the ball in reality.

Instead, they are the result of two complicated processes. First, your senses interact with various things—photons, vibrations, and so on—that are deflected from their normal course by the lattice of field-effects in raw spacetime. This produces a set of perceptions: color, sound, and the like. Second, your brain assembles those perceptions into objects. It can assemble them inaccurately—that’s what happens when you look at an optical illusion, or when you mistake one thing for another thing. What this shows, in turn, is that the process by which we experience things in the world is a kind of thinking. Barfield gives a name to that kind of thinking: figuration.

Alongside figuration, Barfield notes two other mental activities. The first is the activity of treating figurations as things outside ourselves, and thinking about their relations with each other; this he calls alpha-thinking. The second is the activity of thinking about the results of alpha-thinking, thinking about thoughts; this he calls beta-thinking. There are no hard barriers between these three kinds of thinking, and alpha-thinking in particular tends to slide across the line into figuration: if you’re used to thinking about a particular set of objects in a particular way, that habit will shape the way you figurate the perceptions that give rise to those objects.

In this way our ideas shape our reality. This is why, for example, people who speak European languages see orange as a distinct color between red and yellow, while people who speak some other languages do not—for them, red and yellow run right up against each other, and what we call “orange” is for them either a shade of red or a shade of yellow. In both cases, the figuration of color has been shaped by the product of alpha-thinking we call “language,” and the result is that speakers of these two groups of languages literally perceive the world differently.

To Barfield, this is the key to the evolution of consciousness. Throughout human history until the rise of the modern Western world, with one significant exception, people lived in a state of original participation: that is to say, they did not differentiate their thoughts about things from the things themselves, and therefore the world they experienced included their thoughts. When some ancient person experienced a tree or a mountain or a star as a conscious being gazing back at them, that was an actual experience, as real as the typical modern experience of tree, mountain, or star as dead matter with no life, consciousness, or meaning of its own. The ancients weren’t simply making up stories; they were describing the world as they experienced it.

The entire dynamic of history since ancient times, accordingly, was for Barfield the process by which this state of original participation broke down. The leading role in that dynamic, he says, was played by the Jewish people, whose traditional prohibition against image-worship Barfield sees as the decisive turn against original participation. He saw Christianity as picking up the same task and taking it further. As Christianity spread and ousted the older Pagan worship of the gods of nature, it forced people to let go of the habit of original participation and enter into what the disenchanted state we have been discussing, in which the natural world is experienced as a jumble of dead matter, and the difference between inner experience and the outer world became increasingly sharply drawn.

The dissolution of original participation and the coming of Max Weber’s “disenchantment of the world” is not the end of Barfield’s story, however. People in European societies achieved the complete abandonment of original participation in the nineteenth century, a milestone marked by the triumphs of modern science, which made it impossible to avoid noticing the participation of the human mind in the creation of its own experiences. Barfield believed that humanity, with European humanity squarely in the lead, was moving beyond disenchantment toward a new state, that of final participation, in which human beings consciously put meaning and value into nature by means of creative imagination.

In Barfield’s view, this is the God-given goal of the entire process. While the state of original participation involved sensing the divine in nature, and the disenchanted state is that of not being able to sense the divine at all, people in the state of final participation will experience the divine presence exclusively in their own souls. Thus human beings will become co-creators with God. This is an immense challenge, Barfield freely admits, since the human imagination can be turned as easily to evil as to good, but his Christian faith convinces him that ultimately, in the words of Julian of Norwich, “all manner of thing will be well.”

I’m not sure how many of Barfield’s modern readers grasp just how daring this vision of the future of human consciousness actually is. To see that, you have to know your way around the work of the bad boy of late nineteenth century philosophy, Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche’s conception of the human future, as most people know vaguely these days, was the Overman. Despite the vacuous babblings of his tenth-rate imitators in the Nazi Party, Nietzsche was not talking about a racial type. The Overman was always and irreducibly an individual who came to terms with the hard fact that life has no meaning of its own, and proceeds to give it a meaning of his choosing through a perpetually renewed process of self-overcoming.

This is more or less what Barfield was talking about, too, but he set out to make the Overman a Christian, and succeeded in that improbable feat about as well as anyone could have done. It’s an impressive performance, and demonstrates Barfield’s grasp of German philosophy and also his recognition of the serious problems in Nietzsche’s always-uneven oeuvre. He also drew from Nietzsche important elements of the German philosopher’s acerbic history of the decline and fall of morality, and redefined it into a trajectory through which human consciousness moves on its way from the Eden of original participation to the New Jerusalem of final participation.

This same trajectory runs all through Barfield’s work. In explicating the way this process has unfolded in British cultural history, Barfield was at his best, and some of his finest books—notably History in English Words—do a brilliant job of showing how the English language shifted over time from concrete to abstract concepts and from the enchanted to the disenchanted state. It’s when he moves out of this familiar ground that the trouble begins, because Barfield was one of those unfortunate thinkers who cannot find it in themselves to be fair to ideas they dislike.

That stands out most glaringly, perhaps, in his treatment of Darwinian evolution. He insisted that Darwin’s theory was nothing more than the claim that species arose through chance variation. This isn’t even a straw man; it raises serious doubts as to whether Barfield ever actually read The Origin of Species, or even a decent article on the subject in a popular magazine. To insist that Darwinian natural selection is nothing but chance variation is much the same as insisting that an automobile is nothing but the gasoline that makes it go, and then heaping scorn on the notion that anyone can drive around town in a puddle of gasoline.

It would be bad enough if this was the only example of the kind. It is not. His treatment of what he calls “primitive man” is riddled with dismissive oversimplifications of the same kind. Now it is only fair to note that he had the enthusiastic help of a great many late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century ethnographers in taking up that bad habit. Lofty speculations on the allegedly crude and superstitious minds of primitive man—always in the singular, as though there’s only one of him, sitting there on his lionskin, wearing a feathered war bonnet and playing the didgeridoo—run all through the European ethnographic literature of the time. With monotonous regularity, for that matter, those speculations fixated on exactly the sort of linear evolution toward European humanity that Barfield presents.

In the world we actually inhabit, by contrast, the tribal cultures labeled “primitive” by the ethnologists of Barfield’s time differ from each other just as significantly as they differ from European cultures. There is no nice neat ladder of cultures leading from tribal hunter-gatherers up step by step, with Oxford-educated Englishmen poised on the last rung below the still unreached summit. Instead, the world of human culture presents us with an extraordinary gallimaufry of different ways of being human, which vary in the complexity of their technological systems but not in the richness and sophistication of their cultural resources. It is certainly true that the English are by and large better at being English than anyone else, but this doesn’t justify the claim that all other cultures are inadequate attempts to reach that goal!

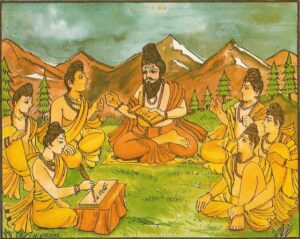

The most important lack of fairness in Barfield’s account, however, is his breezy dismissal of Indian thought, which he lumps in together with the notions of “primitive man” as one more example of original participation. Here he is quite simply wrong, and wrong in a way that inflicts fatal damage on his entire scheme. Indian philosophers were writing about figuration and participation in great detail in the Upanishads, the oldest of which were written well over two thousand years ago. The classic example, repeated and discussed endlessly in Indian philosophical literature, pictures a man who thinks he sees a poisonous snake in the grass. What is actually there in the grass, as it happens, is a piece of cast-off rope—but this is not what the man sees. He sees a snake, because his mind figurates the sensory cues his eyes receive, and then participates in that figuration, giving the rope all the attributes of a snake.

This is as good an example of figuration as anything Barfield discusses. In the vast literature of Indian philosophy, it became a key starting point for centuries of earnest and thoughtful debate concerning epistemology—for those who aren’t fluent in philosophical jargon, this is the branch of philosophy that deals with how human beings know anything at all about the world, and it’s one of the fields that Indian philosophy has explored most deeply. Get past simplistic Western summaries of Indian philosophies, for example, and the concept of the world as maya (“illusion” in too many Western translations) is in fact identical in meaning with Schopenhauer’s account of the world as representation and Kant’s distinction between appearance and the thing-in-itself.

The difficulty is that this is lethal to Barfield’s historical scheme. If Indian philosophers more than two millennia ago were already discussing the insights that Barfield credits to Western science, then it won’t work to claim that the presence of those insights in our time show that modern Western humanity is at the cutting edge of some grand teleological process. If anything, it makes Western humanity a collection of Johnny-come-latelies, finally getting around to insights other peoples reached a long time before.

It also poses a question of no small importance—what happened in the Indian subcontinent in the centuries and millennia after that insight was achieved? The answer offered by history undercuts any attempt along Barfield’s lines to portray the current state of Western humanity as a springboard to bigger and better things. What happened in the Indian subcontinent after the writing of the Upanishads, of course, was a couple of millennia of history as usual. That doesn’t offer much support for Barfield’s insistence that what will follow the modern European discovery of the same thing will be the grand ascent toward final participation he predicts.

None of this makes Barfield unimportant to our future discussion—quite the contrary. His insights simply have to be lifted out of the unworkable historic framework in which he put them. His discussion of the transition from enchantment to disenchantment remains among the best that I know of; it’s simply that his take on what happened before the European Dark Ages and what can be expected to happen after the modern era can’t be justified. It’s entirely possible, as we’ll see, that his ultimate predictions about final participation may yet turn out to be correct in some sense. It’s just that the route there is going to be more complicated than he thought, just as the route to our current state of consciousness involved a great many more twists and turns than Barfield took into account.

In an upcoming post, we’ll talk about those twists and turns, with the evidence of history as our guide. Before we get there, however, we’ve got another couple of important thinkers to contend with—the visionary historian Jean Gebser, who pioneered many of the ideas that Ken Wilber used, and the exasperating but brilliant Traditionalist philosopher René Guénon, who disagreed savagely with everything our first three writers have proposed, but ironically made many of the same mistakes as they did. We’ll proceed to those figures in the next two posts in this sequence.

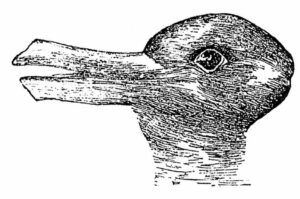

Duck, rabbit, duck!

Sorry. I tried to resist, but, while the spirit is willing, the fingers insist on typing Godawful jokes.

—Princess Cutekitten

Thanks for this great essay! I read Saving the Appearances a long time ago – I must have been around twenty years old. I found it immensely interesting, especially the discussion of epistemology, which was new to me, and at the same time felt a great deal was quite off in his arguments. But I didn’t dedicate enough attention to it to come to some conclusion why things were off, and while my conclusions would probably have been a bit different from yours, your essay does a brilliant job of separating the wheat from the chaff.

Charles Taylor, in A Secular Age discusses similar processes. However, Taylor’s temperament is such that he makes an enormous effort to do justice to each world view on its own terms, including those that are bundled as paganism, materialism and the systems of avowedly anti-Christian thinkers such as Nietzsche (Taylor is a Christian, and a less kinky one than Barfield was).

“Despite his connections with one of the twentieth century’s most famous literary circles, he remains little known outside certain modern intellectual subcultures. That’s unfortunate”

I didn’t know who was Owen Barfield until today. thank you, JMG. I’ve checked there’s a first edition in Spanish, by Atalanta publisher, since a few years ago. I would like to read it soon.

“The most important lack of fairness in Barfield’s account, however, is his breezy dismissal of Indian thought”

Oh my…This is unforgivable in a serious thinker! What a Western hybris…

“the exasperating but brilliant Traditionalist philosopher René Guénon”

Yeah, it’s a little exasperating to read Monsieur Guénon; I’ve read some of his books and I find him sometimes very abstruse and a man with a big Ego, for his disgrace, because he is quiete correct in his criticism against the “modern world” dogma (but he’s himself too dogmatic too in his Traditionalist point of view!).

Great piece and a good explanation of Barfield’s work..

The notion of co-creation itself is arguably very old. “In Platonic terms this meant taking an active part in the demiurgy of the cosmos and becoming a co-creator with the god of creation. The power and authority of Egyptian rites derived from the cooperative mimesis: according to Iamblichus they embodied the eternal ratios … which were the guiding powers of the cosmos.” Gregory Shaw, Theurgy and the Soul. The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus, p. 32, cited in Algis Uždavinys, Philosophy and Theurgy in Late Antiquity, p. 140.

I’m really liking this series. You really bring it into focus what we are talking about. In particular the idea that modern “science” ignores or actively suppresses many things which exist, even when unknown or unseen, in it’s attempt to explain reality. Kind of like how, recently, as a result of the new telescope, “science” has quietly adjusted the age of the universe from something like 12-14 billion years to something like 16-20 billion…. Also, they can’t explain 96 percent of matter in the universe!

I’ve been reading William James recently, in particular, “The Varieties of Religious Experience”. I find it very enlightening in regards to this discussion. Have you read it? Have you written about it?

Lot’s of connections with all of what you are talking about, and, in particular, James’ contention, back in 1902, that science is ignorant of what is really happening inside (and outside) of human beings, and, even more important to him, that they weren’t even attempting to look, empirically, at any of this.

Also, James posits a theory that, whole with some vestiges of “progress”, at the core is of an eternal, infinite “god”, which he attempts to translate into scientific language by calling it the “unconscious” or “subconscious”. Certainly a different “subconscious” than Nietzsche was talking about…

Orion

‘CS Lewis’ ‘Great War’ with Owen Barfield’, a collection of letters they exchanged on Barfield’s theories, contains some evocative diagrams on this subject.

>What modern science has demonstrated is that these qualities—the red color, the squeaky noise, and the rest of it—are not part of the lattice of field-effects in raw spacetime that make up the ball in reality.

Is this what Barfield argues? I take him to be claiming that modern physics itself is an elaboration of collective representations. In other words what “make(s) up the ball in reality” is no more revealed by physics than by any other system of representation.

Alongside your criticism of his dismissal of Indian thought, I’ll note that Barfield is also apparently unaware that the same debates occur in the history of western thought as well, and that Late Antique/medieval Christian thinkers (and Indian for all I know, I’m simply not familiar) not only anticipated his idea of final participation but *actively tried to bring it about* through monastic discipline and contemplative prayer, cf. Eriugena’s notion of man as the workshop of creation, Maximus Confessor’s liturgical cosmos, examples multiply if you know where to look (I’d go so far as to argue it’s pervasive, the default understanding, for centuries).

How does Barfield account for this? I’m not sure, but it does, I think, demonstrate the need to do exactly what you suggest and remove his insights from the historical framework he erects around them.

Hi John. Another great article in this line of inquiry.

I see that the subtitle of Saving the Apperances is: A Study in Idolatry. I may very well have to give this a read. It also reminded me of an essay by Traditional Witchcraft dude, Daniel Schulke, that I’ve wanted to read for awhile: Idolatry Restor’d.

Here is the blurb for that one, for anyone else who is interested:

“The translation of magical power to image is a matter well understood in so-called ‘primitive’ sorcery, in which occurs a mutual embodiment of re-presentation and the Represented. The Fetish, for example, apprehends a reciprocal process between Object and Creator that often begins long before chisels and adzes are set to wood, participating in its own reification. Many of these eldritch forms of image-making were concerned with accessing power, and it was only later, in the context of religious devotion, that their forms densified into ‘mere’ idols. With increasing levels of religious control over art, a Moiré pattern arises between the Artist and the forces of the Divine, which may either suppress individual visionary power in favor of canonized icons, or, when correctly accessed, give rise to an ‘heretical creativity’.”

This has me thinking along lines, that part of going forth into greater participation might have to do with the human capacity for image making -imagination and creativity in other words. It’s a shame I didn’t get in on the Cosmic Doctrine book club, because it seems some of that lingo would also be helpful here, but I’ll take a stab anyway: if the swarm of humanity is learning to develop a mental body, as that mental body gets developed by individuals, and groups or swarms in the collective soul, then perhaps we’ll get to that point of being more participatory again, co-creators.

With regards to the transition to our own Dark Age America, that sense of reenchantment could begin to occur with people as the blinders of “the science -TM” fall away, and a great recognition that we aren’t separate from the rest of the planet, or cosmos for that matter. We might not be that significant compared to some distant sun, and whatever else is in its orbit, but we have things in our own orbits, and do participate. When we can bring more conscious awareness to the participation is when the fun begins.

I’m groping here a bit, but I think towards something useful. Looking forward to the next entries, as always.

& a blessed Imbolc for those of you who celebrate the return of lactation to the ewes!

.

To those who are interested, here are all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared across the Ecosophia community. Please feel free to add any or all of them to your prayers.

If I missed anybody on the full list, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom you hold power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or at the prayer list page.

Finally, if there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

That’s a pretty good drawing of a ruck-dabbit. 😛 Ha!

JMG, do you think the end of original participation is connected to the crossing of the nadir collectively as a species? I think at one point you dated the latter in the late 19th century (1876?) which matches with the time frame given for the former.

(formerly youngelephant, using Z as a random identifier since there’s several with this first name that post)

Watching Ukrainians serve themselves up as cannon fodder, the Overman remains more Nietzschean than Barfieldian.

Fascinating post! I am wondering if perhaps Martin Buber’s, ‘I and Thou’ is largely a lament for the losses inherent in the dis-enchantment of the world?

@ Princess Cutekitten,

That’s probably why Elmer Fudd had such a hard time deciding if it was duck or rabbit hunting season.

Most people commenting on this blog are no doubt aware of the “Weird of Hali” series of novels and related novels by our host, now in the process of being reissued. They are relevant to this theme (disenchantment/re-enchantment) because many of the major philosophical points made at length in these posts are embedded in the novels in less argumentative, more conclusory forms. All very consistently done, I must say.

I learn more about all these topics when re-reading the series in conjunction with following this blog. Each expands on the others and I discover new things each time. Plus, the storytelling is first-rate! I’ve been reading fantasy/sci-fi since the glory days of the 1950’s, and JMG’s writing holds up nicely, in my view.

Plus, one doesn’t have to wonder what his actual views are and are based on, and whether they might have some strange and unsavory philosophical/magical associations, as one does with (as an example, not meaning to pick on him particularly) Heinlein and his buddies.

If you haven’t delved into the stories, they fit together into a unified story but can each be comfortably read as stand-alone novels, and I heartily recommend them.

How much of Barfield’s philosophy is influenced by the religion of progress? That religion took a mortal blow from WW1, but is slow to die, and is still among us today. Much of the work of the other Inkling circle seems to be, in part, a reaction to the dying of Progress as a moral force. However, Barfield, as you describe him, seems to cling the idea that we are progressing to some glorious future.

I won’t comment any more on Barfield until I read more of his work.

Thanks, John

Dear JMG, somehow this brings to mind the contrast between, on the one side, progress and infinite growth (both outward oriented) where the only idea is to keep expanding even into outer space and, on the other side, art or craft which are maybe more internal to the practitioner, and where they can only be practiced and considered by the presence of boundaries. Creative elaboration within boundaries instead of just more and more. In short, an impossible out of body experience vs. birthing something small, but of one’s’ self. Thanks.

I have never heard of the man before, anf probably won’t get deeper into this, but I would still like to point out that the process he describes here which you so elegantly refute by bringing up the upanishad is also very much present in the western tradition.

It’s after all the entire point of Plato’s Republic. So this very modern englishman hasn’t contributed anything new for the western understanding either, something which the aristotelian Nietsche was very well aware off as well.

So paganism 1, barfield nil?

Try as I might, I can’t see any great philosophical conundrum or revelation in someone mistaking a piece of rope for a snake. Unless, says my cynical side, the someone in question is in a social position protected against being contradicted or perceived as mistaken by anyone else present, in which case the rest of them must politely ponder the mystery of a piece of rope taking on all the attributes of an actual snake, why what the honored sir thought he saw must be more real than what was actually there, and how “actually there” is an invalid concept anyhow.

Your Kittenship, you’ll notice that I put ’em through. 😉

Aldarion, Taylor’s on my get-to list, and you’ve moved him up a notch. Thank you.

Chuaquin, I wish the dismissal of Indian thought wasn’t pervasive in Western philosophy, but it’s one of the most embarrassing features of that tradition. It’s not universal — one of the reasons I like Schopenhauer is that he paid close attention to what was known in his time of Indian philosophy, and you can see the influence of the Upanishads on his thinking — but too many Western intellectuals still think, and write, as though nobody east of the Jordan River ever had an interesting thought. As for Guénon, he’s definitely a character; you’re right that his ego is one of the big reasons so few people take his ideas as seriously as they deserve.

Janet, thank you.

Asdf, of course. What makes Barfield’s view Nietzschean is that he seems to think that in the state of final participation the Divine will only be experienced within, and express its creative power through, the human soul. That claim would have horrified Iamblichus, for whom all things participate the One according to their stature, and human beings are only one among countless hosts of entities who have a role to play in the cosmos.

Orion, I haven’t written about James yet, but yes, I’ve read him — The Varieties of Religious Experience was the main textbook for training for the priesthood in the Universal Gnostic Church, so I studied it quite closely. It’s a fine book, and I should probably devote some essays to it one of these days.

Engleberg, thanks for this! I’ll check it out.

Dan, that’s certainly how I read Barfield’s discussion in the first few chapters of Saving the Appearances, though I’m open to the possibility that I misread him. As for Eriugena, Maximus, et al., many thanks for this! I wasn’t aware of these, not being as familiar with late antique and early medieval Christian thought as I probably should be. In the books of Barfield’s I’ve read, certainly, he never mentions these two writers, and in general — as I’ll be discussing in a later post — the late Roman and early medieval worlds are erased by his view of things. (As they have to be to preserve the illusion of linear teleology.)

Justin, good heavens. I gather Schulke has taken up Barfield’s challenge and responded to it with a right good will! That’s good to see, since Barfield’s ideas are — as I hope to show — very much amenable to a radically different take on the nature of enchantment. (I gather that Schulke’s book is sold out and once again out of print, which is annoying; I hope it gets rereleased in a trade format.)

Quin, thank you as always for this.

Robert, is that any relation to a dag-nabbit? 😉

Luke Z, that’s an interesting question. What makes it complex is that the same line has been crossed before by other societies…

Wqjcv, not at all. That whole sorry business is one more dreary display of the mass-mindedness that Nietzsche tried to challenge.

Ken, that’s a fascinating point and one I’ll consider discussing at length. When Barfield talks about original participation as the sense “that there stands behind the phenomena, and on the other side of them from me, a represented which is of the same nature as me”, he doesn’t discuss a critical point — what if the phenomena we’re discussing are, say, human beings? What if they are of the same nature as Owen Barfield? In that case, certainly, original participation is more accurate than the disenchanted mindset that assumes that phenomena are all empty of consciousness, and that, in turn, opens a very big can of worms: are we so certain that other phenomena are equally empty of consciousness — or is that as much an artifact of our condition of consciousness as, say, the duck or the rabbit in the illusion?

Clarke, thank you for this. I’m pleased to report, btw, that the seven volumes of the Weird are currently slated for re-release on October 31 of this year.

Raymond, I think that’s an important factor, both directly — the religion of progress was a massive cultural fact in Barfield’s early life, of course — and indirectly, by way of Barfield’s commitment to the thought of Rudolf Steiner, who was strongly influenced by the general worship of progress in European philosophy in his time. It’s not the only ingredient, though, since the main currents of Christian theology are also very linear in their structure, and one of the two major schools of Christian eschatology — the one currently represented by premillennialism — has a strong commitment to onward-and-upward notions of history and an equally strong similarity to Barfield’s ideas.

Daniel, that strikes me as a very helpful contrast.

Quift, good! The fascinating thing is that Barfield ought to have known all about the way the Greek philosophers explored the distinction between appearance and reality.

Walt, then you’re missing the point. Have you never mistaken thing A for thing B, to the extent that you could swear you saw features that are only present in thing B in what you saw?

About Nietzsche:

“CERTAINLY, Nietzsche was not a philosopher in the strict sense of the word. He is essentially a poet and sociologist, and above all, a mystic. He stands in the direct line of European mysticism, and though less profound, speaks with the same voice as Blake and Whitman. These three might, indeed, be said to voice the religion of modern Europe — the religion of Idealistic Individualism. If it were realised that his originality does not consist in an incomprehensible and unnatural novelty, but in a poetic restatement of a very old position, it might be less needful to waste our breath in the refutation of theses he never upheld.

It is true that we find in his work a certain violence and exaggeration: but its very nature is that of passionate protest against unworthy values, Pharisaic virtue, and snobisme, and the fact that this protest was received with so much execration suggests that he may be a true prophet. The stone which the builders rejected: Blessed are ye when men shall revile you. Of special significance is the beautiful doctrine of the Superman — so like the Chinese concept, of the Superior Man, and the Indian Maha Purusha, Bodhisattva and Jivan-mukta.

Amongst the chief marks of the mystic are a constant sense of the unity and interdependence of all life, and of the interpenetration of the spiritual and material — opposed to Puritanism, which distinguishes the sacred from the secular. So too is the sense of being everywhere at home — unlike the religions of reward and punishment, which speak of a future paradise and hell, and attach an absolute and eternal value to good and evil. ”

https://www.anthologiablog.com/post/cosmopolitan-view-of-nietzsche-by-ananda-coomaraswamy

JMG – yeah, its sold out, and probably quite expensive on the second hand occult market, Weiser Antiquarian, JD Holmes and such. Though I really appreciate all the care people like Schulke put into their fine publishing, it’d be nice to see some trade editions of some of their titles, like they do at Scarlet Imprint. Have the really nice version for those who want that, but put out a copy that those of less means might pick up. That’s one of the reasons I haven’t read it!

I did put Barfield’s book on hold to add to the stack at home.

On another note its quite funny to me having read this today as I had just gotten into a debate defending Steiner to two of my aunts who sent me the following article where he was described as a Satanist.

https://harbingersdaily.com/worldwide-phenomenon-of-sudden-deaths-the-level-of-denial-and-deception-is-mindboggling/

I sent them to several sources, showing that he was not a Satanist, and also that many people involved in Anthroposophy have been very skeptical, at least historically, of vaccines (I’m not sure how those people fared during these last few years.)

Anyways, I would say “onwards and upwards” at this point, but I ain’t feeling it 😉

Great essay as usual! You’ve mentioned Nietzsche here — I seem to remember you discussed him before in your breakdown of Hermann Hesse’s novels, but I cannot remember if Nietzsche got his own essay. If Nietzsche has not yet gotten his own essay, will you please consider it? I find your explanations of philosophers to be the most down to Earth that I have ever encountered, and of course I am willing to take them with many grains of salt. One thing that frustrates me is the modern tendency to rush to fiery condemnation or abject worship of any given commentator based on a single essay, review, or opinion.

Hey John! Since you appear to have referenced it a bit in this post, what do you think about nondualism/idealism? Do you think that the fundamental nature of reality is mental?

I think that we humans (and plants, animals, spirits, demons, and gods/goddesses) are finite minds inside an infinite mind (which has many names like The All, Brahman, the Dao, etc.)

The reason magic works is because we are using our minds to reach out to and influence great minds like spirits, demons, and gods/goddesses, or to the infinite mind. What do you think? Is this view of reality and magic full of baloney, or do you think it might be legit?

Hi JMG,

I have had the experience of misreading a letter, and then catching the mistake, and it was quite alarming. I watched it transform from one to the other quite clearly. So I took from that that if my brain says a thing I’m seeing is something, it can fill in all the necessary gaps to produce something that reliably looks like that thing, adding details that just are not there.

Also I’m really enjoying this series!

Thanks,

Johnny

The classic duck-rabbit image is brought to another level of poignancy here, emphasizing that our differing perceptions can lead to tragic conflict:

https://condenaststore.com/featured/an-army-lines-up-for-battle-paul-noth.html

JMG, I’m starting to get unscientific thoughts on the view you summarize thus:

“Consider a rubber ball. Our senses tell us that it’s red, that it makes a squeaky noise when squeezed, and so on. What modern science has demonstrated is that these qualities—the red color, the squeaky noise, and the rest of it—are not part of the lattice of field-effects in raw spacetime that make up the ball in reality. Instead, they are the result of two complicated processes. First, your senses interact with various things—photons, vibrations, and so on—that are deflected from their normal course by the lattice of field-effects in raw spacetime. This produces a set of perceptions: color, sound, and the like. Second, your brain assembles those perceptions into objects. It can assemble them inaccurately—that’s what happens when you look at an optical illusion, or when you mistake one thing for another thing. What this shows, in turn, is that the process by which we experience things in the world is a kind of thinking…”

Granted that the redness etc is in our thoughts, and moreover an alien from some far planet might have eyes that perceive the ball as jale- or ulfire-coloured or whatever, nevertheless:

Assuming space and time to be finite, i.e. the cosmos to have a beginning and end, it ought in principle to be possible to arrive at a summation or indefinite integral for all the perceived qualities of that red ball, and although the adjective to describe this might be several trillion syllables long, so what – it still means that the ball really is that, and can be accorded the status of objectively possessing that quality. Moreover, our perception of the redness of the ball turns out to be a component, albeit doubtless a tiny component, of that truth. All this is another way of saying that when all the totting up has been done at the end of time, the ball will be judged to have had its own propensity (or destiny if one wishes to be teleological about it) to inspire the sensations it has inspired. Including redness.

Zarbarzun, that’s a fascinating take on Nietzsche, though I’m not at all sure it’s one I would agree with.

Justin, agreed — that’s one of the reasons I’m glad that the publisher that does my high-end projects also issues them as trade paperback. As for the Daily Harbinger, what is it with some Christians, who love to fling around labels like “Satanist” without bothering about little things like truth? I gather that “thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor” got left out of a lot of Bibles.

Ilovemusictheory, I discussed some aspects of Nietzsche’s thought in the sequence of Archdruid Report books that ended up becoming my book After Progress, but that was focused on specific elements in his philosophy — especially his concepts of the Overman and the Eternal Return. I’ll consider someday taking on the daunting task of discussing him more generally.

Enjoyer, the nondualist viewpoint is an interesting account of reality but it’s not really the one I favor. That said, your mileage may vary, and certainly there have been plenty of practicing mages who’ve understood their art in a way not too far from the one you’ve suggested here.

Johnny, exactly. It’s really weird — and weirder still that this goes on all the time and we usually don’t notice it.

Isaac, funny. Bleak, but funny.

Robert, if you want to say that one of the properties of the ball is that under certain circumstances, it produces the kind of sensation in the eyes and minds of primates that we call “red,” I won’t argue. That still makes ample room for Barfield’s point, which is that the color “red” is not a property of the ball alone — it only comes into being when you combine the ball with several other things, such as light from our sun and a human observer. Put it together with light from Alppain and a Tormantian observer, as you’ve suggested, and you get jale instead!

File this under the category of not all minds and brains work the same, but no matter how many times I see the duck-rabbit, I can only see a duck. It never resolves itself into the form of a rabbit for me, no matter how many times I look, or how hard I try. I have to take everyone else at their word when they say it’s both, but my mind simply cannot see it.

Interesting. I am not familiar with Barfield, so all I can do is to throw in a few rash ramblings… I wonder how people like Barfield get the idea that (human) perception is subject to progress. In the way that “I see that the ancient (primitive) people experienced an enchanted world and we don’t. We can’t possibly be worse off than they were (but we seem to be), so there has to be another stage in the future, which will make up for this temporary window of relative misery. Does Barfield write something about how this progress to final perception is supposed to happen? Is it an individual process (like you meditate for a while and so on…) or is it some collective function of a society as a whole?

All in all it sounds a little bit like the dismissal of perception and – as a consequence – the externalization of meaning. Humans can’t really trust their senses, so they can’t (or shouldn’t) derive meaning from what they perceive. Therefore you can’t find meaning in subjective perception but you need social consensus, which also depends on perception, but of a more intellectual type – you can’t easily share feelings, but sharing thoughts is somewhat easier and has the aura of objectivity, because language means abstraction. What’s interesting – especially in the context of the rejection of Indian philosophy – there are ways to root perception in the world, right? Maybe the primitives that experienced consciousness in trees and mountains were just better at it than those who believe in the progress of perception?

Greetings,

Nachtgurke

@ Walt F. re # 21

Many eons ago when I was a kid, I left one of my plastic dinosaurs that I had been playing with, a brontosaurus, half submerged in a pile of sand which was in the garage. (The sand was used during the winter on driveway ice). My older brother, then in his teens, spotted the head and neck sticking up and promptly bolted out of the garage because he has a strong fear of snakes and refused to go back in. I had to actually pull the toy out of the sand and show it to him before he would finally accept it was just a plastic toy. His fear was so intense, his mind could not accept it as anything but a snake. I had to ‘enlighten’ him. Much to his embarrassment. Powerful emotions can skew your perceptions and of course your assumptions. In this case it was just a silly plastic toy. But what if it had been something more significant?

John,

Perhaps because I am reading about Ayurveda, within a few paragraphs I was already asking, “What about Vedic teachings?”; very pleasing to read your discussion.

Related to philosophy and obcession with progress, the following are two concluding paragraphs from Simone Weil’s article “Scientism — A Review” as it appears in *The Simone Weil Reader*.

“””This complementarity is nothing other than the old correlation of contraries which is basic in the thought of Heraclitus and Plato. From the philosophical point of view it has no novelty, but that does not make it the less interesting, because nothing is so interesting in philosopy as a recent discovery of an eternal idea. From the scientific point of view, however, it has great novelty, because from the Renaissance onwards an attempt has been made to impose unity upon the whole of science. This was a mad ambition, and today it has become necessary to introduce the correlation of contraries. A fortunate necessity, because no human thought is valid unless it recognizes this relation. But it is a difficult relation to handle properly, and if scientists want to begin to make use of it they will need a serious philosoophical grounding. Heraclitus, Plato, and Kant could instruct them, but not any contemporary authors.

The progress of science, on the other hand, can bring nothing new to philosophy; and this for two reasons. First, science cannot be anything for the philosopher except matter for reflection. The philosopher can find something to learn from scientists, as he can from blacksmiths, painters, or poets; but not more, and above all not in a differnt way. But the main reason is that there is not, strictly speaking, the possibility of anything new in philosophy. When a man introduces a new thought into philosophy it can hardly be anything except a new accent upon some thought which is not only eternal by right but ancient in fact. Novelties of this kind, which are infinitely valuable, are the result only of long meditation by a great mind. But, as for novelties in the ordinary sense of the word, there are none. Philosophy does not progress nor evolve; and philosophers are uncomfortable today, for they must either betray their vocation or be out of fashion. The fashion today is to progress, to evolve. It is indeed something even more compulsive than a fashion. If the great public were aware that philosophy is not susceptible to progress, there would no doubt be resentment at it getting any public funds. To find a place in the budget for the eternal is not in the spirit of our age. …”””

By the way, apparently related to figuration, there is a model (PP – predictive processing) in cognitive science, as explained in *Surfing Uncertainty* by Andy Clark, in which predictions nominally flow outward while perceptions conterflow inward, these meeting over multiple layers. Nominally, predictions break into subpredictions and perceptions merge into nominally more-whole-than-part perceptions. Clark suggests that at the various meeting points within the various nominal layers, the same mechanisms which transmit both ways also detect in some way the amount of error(s) between prediction flowing one way and perception the other. He suggest that “attention” is related to *how* we are weighting among these errors at any given time. (To me, this fits the notion that command of attention is very closely related to being able to improve in a skill.)

I always liked this example of how our brain works, or doesn’t!

How many F’s do you see in the following sentence?

“Finished files are the result of years of scientific study combined with the experience of years.”

Not 3!

Lol

Orion

JMG,

Looking forward to the posts on Gebser and Guenon, since I’ve read and enjoyed both of them.

This post reminded of an issue that occurred to me reading both Spengler and Toynbee: what is it that differentiates civilisation from non-civilisation.

Toynbee seemed to equate civilisation with control of the environment and the other societies in the neighbourhood. Spengler is more interesting as he suggests its the unity of a set of core ideas. That unity sounds to me like the beta-thinking that influences alpha-thinking and figuration.

Translated into Barfield’s terminology, it sounds like civilisation could be defined as any society that has achieved the breakdown of original participation and has developed beta-thinking.

Does that sound right?

I think that I’m picking up a theme here. Wilber and Barfield are equating modes of perception, thought, and outlook to rungs on a ladder that inexorably climbs from primative to superlative. Curiously, the modes are explained as fundamentally different from each other, but then organized as if one were a building block to reach the next, higher level.

Is it just the Faustian worldview that prevents these guys from seeing each mode as a tool that is suitable in some situations and not others, a tool with various strengths and weaknesses? Or is there something else that prevents the clever, learned men from advancing a notion of a well rounded person* employing different tools in different spheres of their live. Is this a common failing of civilizations in their autumn period of is this unique to our Faustian one?

*I’m aware of the neoplatonic metaphor of man as a chariot with the mind driving and the body and the emotions pulling, this metaphor is used to explain the need for getting all three to coordinate. And I’m aware that the Egyptians had their lives judged in the afterlife to see if they had been good (there is a long list of questions that must be answered in the negative. All of the 10 commandments are in there.) But more importantly to determine if the person had lived, really lived, carped the diem good and propper. But two data points isn’t enough for me to extrapolate.

Thanks for this post, JMG! It’s great to have thoughts like this to think over during the week, even if I only have one RL person I can talk to about this sort of thing!

I couldn’t help but notice the overweening Faustian myth on Barfield’s analysis. I’m not as familiar with vedic philosophy and culture – do you (or anyone else here) know the ways that their civilizational myth-narrative influenced their take on epistemology?

Re: JMG

I am really curious about your metaphysical outlook. I’m more of an idealist, as I stated before. I think that the universe is fundamentally mental, and what we call matter can be reduced to mentality, specifically the mentality of a universal mind, which we are finite sections of.

I know you’re not a materialist, so you don’t think mind is reducible to matter, and I agree with you. So are you a dualist, and you think that mind and matter are both irreducible? Or do you have another position?

Either way I respect your worldview, because I think the only untenable one is materialism.

Good Lord, that poor man had a very limited appreciation for the incredible potency of creative imagination! It is much more than just a deus ex machina for lazy philosophers to bail themselves out with. Barfield’s “original participation” would require a very healthy creative imagination to even be able to sense the divine around us. The “disenchanted state” that Barfield envisioned overtaking the modern world (Yes, his creative imagination was definitely working overtime!) would require a unhealthy creative imagination — potent, but unhealthy. His “final participation” would also require creative imagination, but why would anyone want to waste it by smearing all their inventive delusions over nature, under the noble guise of adding meaning and value to it? That sounds an awful lot like scientism to me… or certain repressive branches of Christianity… or even the warped vision of heaven that Barfield’s chum C. S. Lewis spewed up in his final Narnia novel.

By opening a gateway in our perception, creative imagination can act as a potent sensory tool, used by mages, psychotherapists, priests, dream interpreters, etc. to gain awareness of the unseen dimensions and patterns all around us. That particular potency Barfield prefers to relegate to some mere “primitives” in his strained hierarchy of intellectual/ontological accomplishment. That wouldn’t seem quite so smugly insulting were his hierarchy not then to trot out Barfield’s own style of blinkered perception as the apotheosis of all human existence. Really, Owen? If we could all just do a better job of mimicking European Christian armchair intellectuals, God’s kingdom would finally descend here on earth, as it is in heaven?

Do these philosopher-kings ever think to have someone outside their rarified class go over their theories before publishing them, just to make sure they don’t read like unintentional parodies of too much self-applauding navel-gazing? OK, so that is overly harsh, but, after being subjected to Wilber’s self-proclaimed genius, it is getting hard not to laugh at all their dated profundities. I will certainly read Saving the Appearances to learn where Barfield might not have so blatantly missed the mark.

Misconstruing creative imagination as nothing but a magical hall pass that might allow humans stealth entry into the realms of the gods, where we could then take over and prop ourselves up as false gods, is truly a failure of human imagination. Were humans, in our considerable neurosis, to begin to “experience the divine presence exclusively in [our] own souls,” why on earth would we feel any need to look to the gods again, let alone share co-creation with them? Once we’ve conceitedly placed ourselves on the same footing as the gods, we’re in the perfect position to haul them off their thrones and bludgeon them to death in a bloody palace coup. If that were actually any sort of God-given goal in our being here, it would certainly make for quite the self-goal!

How did Barfield come up the peculiar notion that disenchanting everything outside himself would somehow make him a co-creator with God? A partner of the devil potentially, but definitely not with God. He would have had to start from the amazingly dubious, as well as heretical presumption that God is not one of the many things outside himself that he was so ruthlessly disenchanting. His eccentric belief that divine presence could somehow exist exclusively inside of us sounds more like a euphemistic, Humanist cover for declaring man to be God. Ever since the Age of Humanism began, so many Western philosophers keep trying, with such dreary regularity, to shoehorn all of their mental calisthenics into the same predictable dead-end of man (ever so humbly, I’m sure) replacing God.

The Western mind seems to be unable to escape its enduring fantasy of eventually getting to roleplay Jupiter deposing Saturn for all of eternity — a rudimentary fantasy of “final participation” too good and pure to be marred by the unwelcome realization that Saturn had similar over-optimistic goals in deposing Uranus before him. Is it just deranged patricidal turtles all the way down? How these Progressive rationalist fanboys can justify calling themselves Christians is truly a divine mystery.

I continue to enjoy this series immensely. I’ll have to revisit Saving the Appearances, which I read years ago, and likely mostly went over my head.

An observation and a question, if I might:

The observation: it strikes me that all three of the Inklings I’m familiar with (Tolkien, Lewis, Barfield) got rather a lot of, and rather good, creative output from the tension of trying to reconcile their obvious love of at least some “pagan” things with their non-negotiable Christianity. While I may not agree with the conclusions they reached, the process sure gave us some interesting outputs!

The question: in an interview I listened to today, the guest spoke about a Greek-French philosopher named Cornelius Castoriadis – are you at all familiar with him, and if so, any thoughts?

If not, he argued (as I understand it) that cultures are built on irreducible, mythic “images” that are so fundamental to how they view the world, they can’t be broken down further – to understand the culture, you have to accept them as premises. The main contrast the interviewee drew was between the Hebrews, who believed a rational, benevolent entity created all of Being, versus the Greeks, who believed Being arose out of Chaos in a fundamentally violent/transgressive act (or series of acts). It seemed interestingly relevant to both the discussion of figuration in today’s post and Spengler’s views on the birth and development of cultures, but so far all I’ve looked into him is to skim his wikipedia page.

Thanks again,

Jeff

Bravo! You’re fair to Barfield, one of my favorite thinkers. Quite fair. To be honest, I think the world looked so astonishingly different in 1930 he can to some extent be forgiven… although it’s a serious lapse for a serious thinker which he is. What interests me more is your proposal to disentangle his insights from the standard World Exgibition worldview and develop them more adequately. Final participation is the end goal for every creature, but…you’re so right. Lots of twists and turns before you get there. No straight upward line. And the beatific vision wont be purely solar…or else, why creatures at all? No theres more work to do. That’s in a way all final participation can insist on. Earth forces, got left out for starters. Jung is a good counter weight to Dante. Just clues here for now…thank you generous host.

Dan is so right about erigena the Celt and maximus whom erigena adored. Karl Lowith btw has an interesting book that works backwards in time through theology and their view of history. The farther back you get the less notion of material progress. Orosius for instance.

Thank you for exploring this theme. As a Waldorf educator one works actively with this concept of the evolution of consciousness and the transition from participatory consciousness to conceptual consciousness; however, I have always struggled with taking these very real changes and applying them to some grand historical motif as Steiner did. Needless to say I’ll be patiently waiting to see where the next several posts take us. I’m truly intrigued.

I see a slug and its reflection on water.

Anonymous, interesting. It’s true — not all people see both sides of those ambiguous drawings. I don’t know of any research into why that is, though.

Nachtgurke, the grand delusion of 19th and 20th century European thought is the insistence that European intellectuals are at the cutting edge of human evolution and every other culture throughout time is simply part of a process that leads to them, and beyond them to some glorious future or other. Delusions of grandeur on an epic scale? Sure, but that’s the way these people thought. A very few European thinkers managed to break free of that; Spengler was one of them, and Josephin Péladan another (and a far more eccentric) example; but most couldn’t see past that fantasy at all.

JVP, hmm! Thanks for this; I haven’t read Weil yet, and clearly there’s a lot to consider in her work.

Orion, I spotted five, for whatever that’s worth.

Simon, hmm! I’d have to think about that, but it’s at least a plausible hypothesis.

Team10tim, good! Yes, that’s part of what I want to explore. The rest will have to wait until we’ve reviewed a few more thinkers and then taken a very hard look at history.

Sirustalcelion, my background in Indian thought isn’t sound enough to allow me to answer your question about that, but you’re right about the Faustian character of Barfield’s thought.

Enjoyer, are you at all familiar with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer? His ontology and epistemology without his pessimism — that is to say, something like the synthesis Eliphas Lévi proposed — is the basis for my thought. I don’t believe that all things are mental because I see “mind” and “matter” as two of several grades, to use Schopenhauer’s term, of an underlying reality that cannot be described as either. (Schopenhauer, with many caveats, used the term “Will” for it, but acknowledged the inadequacy of the term.)

Christophe, where do you think Lewis got the idea? He was very strongly influenced by Barfield, among others. As for the rest — well, you might consider reading some of Barfield’s work and sitting with it. It’s got its problems, but it also raises some fascinating issues.

Jeff, (1) yes, very much so; have you read Tolkien’s essay “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”? He talks at some length there about the use of Pagan imagery by a Christian writer — he’s nominally talking about the author of Beowulf, but it’s clear that he’s also discussing himself. (2) No, I haven’t encountered Castoriadis. That’s an interesting proposal.

Celadon, you’re welcome and thank you. Jung is one of the core figures I’ll be evoking as we proceed, and also Yeats — there’s much more to be said about enchantment than Barfield got around to saying, but his basic analysis will help us get there. What’s the title of the Lowith book? That might be worth a read.

Zosmia, you’re most welcome, and thank you for the feedback! It’s precisely the grand historical narrative I want to undercut here. Steiner was a pioneer, and like most pioneers he combined extraordinary insights with outworn ideas whose irrelevance hadn’t yet become clear; his ideas of evolution in history were too heavily freighted with early 19th century schemes of teleology and progress, and his genuine achievements need to be extracted from the less helpful framing. It’ll be a while before we return to the movement from participatory to conceptual consciousness, as I want to touch base with several other thinkers first, but we’ll get there.

Lunchbox, ha! I like it.

(BTW, I’ve deleted more comments than usual today. I’m not sure why, but Barfield seems to attract some very odd word salad, and also some rant-a-matic output. If your post didn’t get through, please review the text above the comment box, and remember that I do indeed delete things that don’t follow those rules.)

Meaning in History. He was a Lutheran theologian. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_L%C3%B6with. It’s pretty damning, for those with any theological loyalties, for the religion of progress and Christianitys ill fated alliance with such ilk. He argues that hope has to be as naked a virtue as faith, which I take to mean, dont expect to reap its fruit in history. Theres a great quote about moderns being blind compared to ancient or medieval, in the Wiki article, because they try to see with one eye of faith and one of reason and therefore cannot see a whole. They see dimly. Modernity cant decide if its greek or biblical. They try and have both. I’ve wrestled with that quote a lot. It seems to bear on Barfield and his attempt to have both, but see clearly. Perhaps can be done but not that way.

What if I am staring at my phone figurating the words while I am walking, and the I run into a tree I did not see, and then look up and see the tree laughing at me?

Does the tree exist?

Re Re: JMG

I’ll look into Elipha’s metaphysics and tell you what I think of it!

It is well known that all Druids take a (sort of) secret vow to sneak as many really bad jokes as possible onto the Internet. That’s where they all come from. (The jokes, not the Druids.)

Fnord.

Are there any of these “ladder of progress” ideas that have a Congolese pygmy woman on the top rung?

Nah, thought not. As soon as you break from the original path of life, you start concoting excuses for why you are so miserable, alone, and out of breath all the time and call it philosophy. You then put yourself on the top to make yourself feel better, and ignore everything that doesn’t fit in your ivory tower, like how the only reason you can sit around doing thinky thoughts is because someone else is ironing your robes.

“The world is alive, kill the world, make it live again just how we like it” is this guy’s dull response to being bullied at prep school or something.

@JMG, (sorry for the long comment)

In media ecology, Marshall McLuhan made similar points about the changes in consciousness and perception after the introduction of printing press.

He also claimed that electrical media would undo the process, so he was probably closer to your “cyclical” vision of history than to the idea of linear progress. Looking at the irrationalism of the media, he was probably right.

But do I understand it correctly that you think that disenchantment never really happened and was only Weber’s construct?

To me, that seems doubtful at best. I lived close enough in time and place to the left-overs of “enchanted” cultures to at least suspect a deep difference in consciousness. The fact that a number of people in Weber’s circle dabbled in magic does not mean much: it can be explained away with quixotic nostalgia and reconstructionism, or status-signalling by an intellectual elite. Weber’s intellectual friends would have fled in horror from a real enchanted culture.

The communal experience of “original participation”, popular ritual magic and superstition were put on a leash by Christianization and basically ended with the Reformation in Protestant countries. They survived in Catholic countries until nationalism and industrialization took hold.

Enlightning to me is a 1945 anthropological novel by Carlo Levi, Christ stopped at Eboli, about surviving pre-Christian, pagan communities in remote villages in Southern Italy.

I do agree with McLuhan that oral cultures are coming back thanks to digital, mass-media “enchantment”.

Hi John Michael,

“grand ascent toward final participation he predicts”

Mate, we’ll be very lucky indeed to avoid a grand descent! 🙂 These thinkers need to get a day job…

It’s funny but I’m surrounded by sort of old forest. One or two trees predate European settlement. All the same, the footprints of humanity have walked these forests for tens of millennia doing what needed to be done. Being here has had an impact upon me that is hard to describe, but when I look at a tree I think to myself: Is it getting enough light; Is the tree too crowded; How’s the canopy; What’s eating the tree; How’s it growing; Is it in danger of falling on my head etc…

Most people see only ‘tree’, which is a very disturbing way of thinking, but you hear that mode of thinking talked about and reported on all the time. Tree… Sure…

The thing is, with that way of thinking the bloke was pushing for, turning something into an object, or an abstraction, means that you can abuse it. Ascent sadly looks to me like a form of power and control. However, take that thought and run to the logical end point, and it’s not good. And here we are today.

That way of thinking about the world is a tool, it shouldn’t be a blindfold. Sheez, I thought we were smarter than that. Guess not. 😉 But you already knew that.

Cheers

Chris

Hi John Michael,

Oops, almost forgot to ask. So did the good professor Tolkien ascribe the enchantment to the Elves and the diminished race of Numenor soon to be a product of the past?

Cheers

Chris

The ball is actually objectively red as per the modern definition in physics.

It is not matter of perception. In normal conditions (which covers the material realm where humans live), an object is red if it reflects radiation in the 620-750 nanometer range of light. This is a property inherent to the object not the observer.

In Science, the problem with figuration/perception in general is a problem of point of view, experience and definition. Like mentioned above in several comments, the problem with scientific/materialistic characterizations is that the description of a simple object like a red ball would take a several 1000 pages tome of physical properties listing. Perception shortcuts that intellectually exhausting pattern to move on…

There are 6 F’s….

On paper I think it works better. Our minds ignore the F’s in “of” for some reason. Maybe because it is a v sound instead of f? Usually people only see 3.

Orion

@JMG #46 re: Tolkien and Castoriadis

1) Only excerpts, though I got the collection of essays that includes it last year and it’s been on the “to read” pile for a long time. I suspect I’m going to need to give Beowulf some serious attention as a source for meditation themes sometime after I finish working through Dolmen Arch, and that essay is on my list of commentary to accompany such an effort. I have found the distinction Tolkien made, I believe in that essay, between “allegory” and “applicability” a very helpful one (I encountered that in, I think, Shippey’s Tolkien: Author of the Century, or perhaps The Road to Middle Earth).

2) Reading a bit more about Castoriadis, I’m getting a thorough mix of “this could be interesting” and “pretentious horse manure” signals about his work – as a kid, he was a doctrinaire Maxist, but somehow got on the wrong side of the post-war regime in Greece and so fled to France, where he grew up in the same intellectual environment as French post-Freudians, post-modernists, and post-whatever-else, and in many ways, seems to be of that same oeuvre. On the other hand, it seems like he believed different cultures were genuinely different, that myth and imagination tell us important things about them, and managed to work out the common worldview of Marxism and Capitalism, and had scathing critiques for both. Altogether, I get the impression there might be a lot to wade through that I find less helpful/disagree with, but that he might have some worthwhile insights and a helpfully different viewpoint from most of the thinkers I draw from. One more thing to add to the ever-more-precarious “to read” pile!

Cheers,

Jeff

thanks for the reminder of OB, I’m always puzzled by claims of disenchantment in these post WW2 days, while Europeans got less involved with their churches religious politicians and religious movements have remained as dominant players in most of world affairs especially here in the US which of course as the global hegemon infects everything.

Barfield’s prediction of a new spirituality springing from the creativity of the human mind and not humans relation with nature or physical objects is happening in a twisted way in the progressive elite in the Western World. Without a doubt “Wokeism” is driven by the failure of the religion of progress, as has been described on this blog. But in this effort to redefine “Progress” as moving toward some glorious future of social justice for all, they have begun creating a weird spirituality that is a product of their fevered minds. Yes, it bears as much resemblance to well developed spiritual construct as The Spice Girls do to the Miles Davis Quintet. But it does seem those driving the woke agenda would like to be the high priests of a new religion that springs from their minds and bears no resemblance to concrete objects or experience with nature. Moving the deplorables away from their grubby existence trying to pay the bills, or worshipping old ( anti-LGBTQ religions) seems to be taking on the trappings of a religious crusade to which only the anointed ones hold the keys. This was driven home by the recent survey done among leaders in Journalism’s Academia showing support for the removal of the idea of objectivity in journalism, to be replaced with the advocacy of social justice. It is on purpose that the notion of Social Justice has been massaged in to a very abstract concept that the “unwashed” can no longer understand, or make sense of. This means they must be told what it means by the high priests of this new religion.

@ Anonymous re #31

It’s because of the ambiguity of the image. Such images are almost always drawings rather than photos because a drawing can be deliberately made confusing by the artist, by muddying or leaving out just enough detail to make it unclear what it actually is. There’s the drawing that looks by turns like a vase or like two faces staring at each other. Or the one that can either be a young lady staring off to one side or an old crone glowering at you.

In my above comment, it wasn’t until I brought the plastic toy out of the dim light of the garage which gave it a sort of ambiguity and out into bright daylight that my brother could finally see it for what it really was. Once your brain gloms onto an interpretation of what it sees, it can be pretty hard to convince it to see it differently unless more detail is provided.

I created an image taking the duck/rabbit and drew in the body which would probably make the rabbit clearer to you and rob it of its ambiguity, unfortunately I don’t know how to post an image here.

I think the major work of Castoriadis is The Imaginary Institution of Society, MIT Press, 1987, Kathleen Blamey, English translator. I can’t remember what led me to it, or what Castoriadis is best known for, but the following passage from the Preface is, I think, germane to this discussion.

There exists no place, no point of view outside of history and society, or ‘logically prior’ to them, where one could be placed in order to construct the theory of them–a place from which to inspect them, contemplate them, affirm the determined necessity of their being-thus, reflect upon them or reflect them in their totality. Every thought of society and of history itself belongs to society and history. Every thought, whatever it may be and whatever may be its ‘object’, is but a mode and a form of social-historical doing. It may be unaware of itself as such–and this is most often the case, by a necessity which is, so to speak, internal to it. And the fact that it knows itself as such does not take it out of its mode of being as a dimension of social-historical doing. But this can enable it to be lucid about itself. (p. 3; emphasis original)

Rashakor brings up a point long known to chemists (my other degree).

“Like mentioned above in several comments, the problem with scientific/materialistic characterizations is that the description of a simple object like a red ball would take a several 1000 pages tome of physical properties listing. Perception shortcuts that intellectually exhausting pattern to move on…”

Case in point, Xanax, AKA Alprazolam, made by, Synthesis of 1-methyltriazolobenzodiazepines (alprazolam type) is possible by heating 1,4-benzodiazepin-2-thiones with hydrazine and acetic acid in n-butanol under reflux.

Chemists draw a lot of pictures. You can see why.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alprazolam

If in a state of original participation you consider a tree as made of the same sort of stuff as you or your neighbor, then cutting down your neighbor is no more or less morally wrong than cutting down a tree.

Have I got it right?

Even before I read the second half of the essay, I was thinking: This guy clearly has no idea that Indian philosophy went through the same ideas long before him.