The Holy Grail! Most people think they know a certain amount about it, even if their only exposure to the legends of the Grail come from watching Monty Python and the Holy Grail and some forgettable film or other starring Harrison Ford. You can check this by asking a dozen of your friends to tell you everything they remember about the Holy Grail. Unless they’re serious geeks, or simply know nothing at all about the subject, most of them will tell you that it was supposed to be the cup that Jesus of Nazareth used at the Last Supper, that King Arthur’s knights went looking for it, and wasn’t there something about a rabbit with nasty vicious teeth? One or two of them might recall that Sir Galahad had something to do with the Grail, and so did the castle of Caer Bannog—or was that the rabbit again?

If this is what comes to your mind when you think of the Grail—well, setting aside the dreaded Rabbit of Caer Bannog—you’ve just demonstrated the enduring effect of medieval spin doctors. Yes, spin doctoring goes back to the Middle Ages, and quite a bit further still, in fact. The version of the Grail legend whose last dim echoes cling to most minds these days is the result of the work of some capable medieval practitioners of that dubious art. It has almost nothing in common with the oldest surviving forms of the legend. There were solid reasons for that, which we’ll discover as we proceed with a quest of our own.

That quest begins with Chrétien de Troyes, a French poet of the twelfth century. He’s the author of the first surviving Grail story, Perceval, ou la Conte du Graal, which was written sometime around 1190. Chrétien had already written four other Arthurian stories, all of them bestsellers by the standards of the time, and helped kickstart the fad for Arthurian romances that played so huge a role in shaping the imagination of the Middle Ages. He claimed that he got the story of Perceval from a book lent to him by one of his noble patrons—a claim which, weirdly, most modern scholars dismiss out of hand.

The story Chrétien told is a very strange one. It begins with a young man raised in the forest by his widowed mother, in complete ignorance of his heritage. He meets a group of knights riding by, and mistakes them for angels; once this is cleared up, he decides that he wants to become a knight, and goes off to have adventures, abandoning his mother, who dies of grief. After a visit to King Arthur’s court and an assortment of other adventures, he comes to the castle of the enigmatic Fisher King, who is wounded and cannot heal. There he sees a curious spectacle: a procession in which, flanked by candles, a bloody spear and a grail are carried past. Having been told that it’s rude to ask too many questions, he doesn’t ask the Fisher King about this.

He spends the night in the castle, and wakes the next morning to find it empty. Later, a strange and supremely ugly maiden tells him that if he had asked about the grail, the Fisher King would have been healed of his wound. She also tells the young man his own name, Perceval, which she knows but he does not. Perceval then vows to find the castle of the Fisher King again and ask the question, and rides off to another set of adventures…

…and it was at this point that Chrétien de Troyes died, leaving the story unfinished. Nobody knows how he meant to end it.

Let’s note something before going on. The word “grail,” graal in the original, was a provincial French word for the kind of broad flat dish that was used to serve a large fish at a medieval banquet. The grail, in other words, wasn’t originally a cup at all: it was a platter. Nor did Chrétien call it the Holy Grail; he refers to it, rather, as the rich grail.

Chrétien’s story was wildly popular. Three other writers of the time wrote their versions of what came next in the story; their three Continuations, as these are called, soon got mixed up with the original. Another author, Robert de Boron, wrote his own version of the whole legend, which brought in the Christian element; in his three books, Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, and Perceval, the grail became the platter (not the cup) that Jesus used at the Last Supper, and a great deal of theology found its way into the story.

Then there was the version that bears most directly on our quest, Parzival, which was written around 1210 by Wolfram von Eschenbach and ranks as one of the supreme masterpieces of medieval German literature. Wolfram also claimed to have gotten the story from a book—once again, weirdly, modern scholars dismiss this claim out of hand—but it’s a different story from Chrétien’s, in crucial ways. Wolfram’s Grail is a stone, not a platter; he describes it as “the longing for paradise,” and explains that it has a name: lapsit exillas. We’ll get to that shortly.

Between them, Robert de Boron and Wolfram von Eschenbach threw open the floodgates. Grail legends accordingly surged across the European landscape during the half century that followed. The earlier ones, published before 1225 or so, had certain things in common. They had Perceval (or Parzival, or Percival, or Perlesvaus, or some other version of the same name) for their hero; they included some version of the strange ceremony at the Fisher King’s castle; and in nearly all of them, the Grail is associated with secrets of a religious nature. Those secrets may be holy names or mysterious prayers or simply “the mystery of the Grail,” but it’s stressed over and over again that these are profound and frightening secrets of deep importance, and they have to do with the essential themes of Christian faith.

To anybody in the medieval Western world, those hints and warnings could have only one meaning: heresy. Which heresy is no secret, either, because Wolfram gives the game away. The only reason that this isn’t recognized is that modern scholars have engaged in the most spectacular contortions to avoid talking about the obvious meaning of that phrase lapsit exillas. I’ve seen it interpreted as lapis exilis, “stone of exile;” as lapis ex caelis, “stone from heaven;” as lapis elixir, “elixir stone;” and any number of other equally improbable ways. (I don’t know of anyone who’s interpreted it as Lapsang Souchong and announced that the Grail was really a teapot, but equally absurd arguments have been made.)

What makes this fascinating is that lapsit exillas has a straightforward Latin meaning. Lapsit is a standard poetic contraction of lapsavit, “he, she, or it fell.” Exillas is two words, ex illas, “from among them,” and as anybody with even a basic familiarity with Latin knows, ille and its derivatives have an honorific force. “From among Them” catches some of the flavor.

The name of the Grail, then, is “She fell from among Them.” We’re talking about Gnosticism, of course. The central Gnostic myth tells of how Sophia, Wisdom, the last emanated of the divine Aeons, fell from the world of light through her desire for independent creation, and by that act brought into being the fallen world we live in. Her fall, her repentance, and the redemption through wisdom she offers to the sparks of divine light that fell with her into material existence: these sum up the narrative structure of Gnosticism.

Nor was Gnosticism anything like an unfamiliar concept at the time. The years between 1190 and 1250, when the first great wave of Grail legends were written, were also the heyday of the Cathar heresy, a rival to established Christianity that came within an ace or two of displacing the official church in much of France and significant parts of Spain and Italy as well. The Cathars, called Albigensians (“those people from Albi”) by the church, were Gnostics, and their apogee marked the last great flowering of the Gnostic faith before modern times. It’s a matter of historical record that the Inquisition was created to exterminate the Cathars, and only turned to other victims once the Cathars (and half the population of southern France with them) had been wiped off the face of the earth.

It’s at this point that the spin doctors become relevant. They were monks, most of them, writing in a handful of monasteries in France and England, and their creation was the version of the Grail legend that most people in the English-speaking world remember today. They got rid of Perceval as quickly as they could—he was married when he found the Grail, after all, and we can’t have that!—and replaced him with a newly invented knight, Galahad.

Some of my readers may be familiar with the term “Mary Sue.” For those who aren’t, this is the standard term among writers for a fictional character who exists solely to act out the author’s wish-fulfillment fantasies. (I’ve heard the term “Marty Stu” used sometimes for the masculine equivalent, which is just as common, but I prefer to avoid assuming Mary Sue’s gender and use the original for both sexes.) Mary Sues as main characters make for a very specific kind of fiction, utterly compelling to readers who share the authors’ insecurities and fantasies, utterly unbearable to those who don’t. This makes them tolerably useful, in that you can very often use the response to a given Mary Sue to tell quite a bit about the person who responds.

Galahad’s a great example of this. He’s the supreme Mary Sue of the Christian mystic. All the Christian mystics I’ve ever met think he’s wonderful, and wish they were more like him. Everyone else thinks he’s an insufferable prig. He drips purity out of every pore, and this makes him invincible in combat. He shows up at King Arthur’s court, proves that he’s destined to find the Grail by sitting in the Perilous Seat that’s swallowed up every other claimant, gallops off at top speed to find the Grail, promptly finds it, drops dead on the spot in an odor of sanctity so strong it’s practically a stench, and is wafted straight to Heaven by a gaggle of angels.

Then the Grail, which in these stories is of course the cup of the Last Supper and the chalice of the Mass, is hauled away to heaven as well, so don’t you even think of looking for it, you naughty heretics! The mysterious ceremony at the Fisher King’s castle vanishes without a trace, too, replaced by the standard Catholic Mass. It’s a very efficient transformation of a once-threatening narrative, and it makes for a good lively story, at least if you can stand Galahad. Interestingly, the spin doctoring continues in certain circles; you can find any number of recent Christian mystics who insist that the Galahad version of the story is the only one that matters.

Richard Wagner, to circle back to our theme, was not a Christian mystic. His attitude toward Christian mysticism can be gauged quite precisely from the fact that Galahad appears nowhere in his version of the Grail story, which he duly named Parsifal after its main character. Wolfram von Eschenbach was his main source, but he was clearly aware of the whole trajectory of the Grail story, and drew on multiple versions for his own purposes. In a certain sense, Wagner’s Parsifal was also a Mary Sue, but his Mary Sueness was handled much more deftly than Galahad’s, and it also applies to dimensions of human experience much more commonly encountered than the travails of the devout Christian mystic. We’ll get to that as we proceed.

Yet the Grail also has a distinctive role in Wagner’s artistic cosmos, and it’s one that builds on the themes we’ve been discussing all through this sequence of posts. Two weeks ago we talked about the way that in Wagner’s view, the archaic mythic image of the sun-treasure got split apart in recent centuries, divided like so much else in our sundered world into sacred and secular halves. The secular half of the sun-treasure archetype ended up attached to money, that system of arbitrary tokens we use to manage the exchange of goods and services in modern societies. That archetypal force, Wagner held, goes a long way to explain the immense and irrational magnetism that money exerts on the modern psyche.

There’s also the sacred side of the division, however. Here Wagner was just as explicit: he argued that the sacred dimensions of the archaic sun-treasure ended up concentrated, in the imagination of the Western world, in the legends of the Holy Grail. It’s an intriguing suggestion, but to make sense of it we’ll have to take a closer look at the division itself.

Most societies around the world and throughout history haven’t drawn a hard and fast line between the sacred and the secular. The two interpenetrate so completely that many of the world’s languages have no word for “religion.” This isn’t because there’s a shortage of activities of the kind we call “religious.” It’s because the people who speak these languages had no need to separate them out from all other human activities.

In English, to point up a comparable situation, we have no general word for “activities done in response to the weather.” We open umbrellas, put on or take off sweaters, dive into swimming pools, turn up the heat or the air conditioning, and do quite a few other things to respond to the weather, but we don’t set them apart from all our other activities and assign a special word to them. In the same way, people who speak the languages we’re discussing say prayers, make offerings, learn and repeat sacred stories, and do most or all of the other things that we call “religious,” but they don’t set them apart from their other activities and have a general word for “activities done in response to the gods.”

There’s actually a straightforward reason for the evolution of that category in our society. It’s an act of collective self-preservation. It so happens that the religious specialists in most other cultures don’t claim infallible access to the will of the Divine. Ours do—and this is just as true of Protestant clergy who insist on the infallibility of the Bible as it is of Catholic clergy who insist on the infallibility of the Pope. It so happens that religious specialists also tend to be sources of very bad advice about subjects outside the realm of faith and morals, and this hasn’t kept them from offering such advice and claiming infallibility for it—and here again, this is as true of the Bible as it is of the Pope.

Thus in the Western world we’ve carved out a special category of “things that religious specialists are allowed to monkey with,” which we call “religion.” Until our religious specialists finally get around to noticing that they have no more business handing down edicts about geology or economics than geologists or economists have handing down edicts about theology, that division will probably have to remain in place as a matter of sheer survival. All this, in turn, serves as background for Wagner’s insight.

He was right, of course, that the legends of the Grail emerged in Europe around the time that European religious specialists started to claim the right to tell everyone else what to do about everything, and he was also right that the division between the two sides of the ancient sun-treasure widened as the claims of religious specialists became more extreme. It’s interesting to note, though, the divergent trajectories of the divided treasure. As money came to dominate the collective imagination of the Western world, the Grail faded from sight—and not only the Grail.

All the old mythic images stole away from the increasingly glaring light of the conscious mind and found new homes in the darkness, where they could exercise their power unnoticed. This didn’t decrease their power, quite the contrary: it’s the mythic image you don’t recognize and therefore can’t take into account consciously that has the most power over your mind. Thus one great advantage of being mythologically literate is that you can choose the narratives you use to understand the world, instead of letting the old mythic patterns play merry hob with your mind in ways you can’t anticipate or even perceive.

Thus it’s inaccurate to see the Grail as a counterbalance to money, a sacred image holding the balance vis-a-vis the secularized image of money. Money exercises the whole emotional and imaginative force of the ancient sun-treasure. It’s just that it does so in a covert way, slipping through the crawlspaces of the Western mind to twist our thinking into its own shape. Most people accordingly go through their whole lives without ever noticing that they’re stumbling through the trajectory of an archaic myth, seeking a Grail that they’re destined never to find, because they can’t get the clarity they would need to ask the right question at the right time.

What makes the Grail legend important in Wagner’s mature thought is not what it is, but what it could be. He saw the Grail—or rather a galaxy of ideas and insights that rotated around the old image of the Grail—as a potential answer to the dreadful conundrum posed by The Twilight of the Gods, the riddle that brought him to the brink of suicide and drove George Bernard Shaw to betray everything he once believed in. Is it possible to get the Ring back to the bottom of the Rhine without burning the world down in the process? In less mythic language, is it possible to break the spell of commodification by any means short of the decline and fall of civilization and the coming of a new dark age?

Wagner thought that there might be. In the final installments of this series of posts, we’ll consider the option that he proposed in his last opera.

Wasn’t that what Kane went looking for in the swamp of the toadmen? Oh, wait, that was the bloodstone. And it was on a ring too, go figure.

The Grail was a platter subject to spin doctoring? That’s quite appropriate since metal spinning is the art of turning a sheet of metal into a pot or bowl. It’s quite capable of turning a platter into a cup.

The curious can look up metal spinning on YouTube.

Dear sir, I protest your remark about the glorious third Indiana Jones movie! It has won a special place in my heart from when I first watched it as a boy. And so long as I live it shall not be forgotten!

Thinking about it now. It would be a nice touch to watch it again. I have not seen it in more then a decade, so it might be nice to see how much it aged. And how much it aged for me.

Just thinking about it, even without today’s essay, it has some silly tests of character, and the grail must have unrealistic “wash away gunshot wounds” healing powers.

I wonder how I would react watching it again today…

Equating it with gnostics, that, wow. It makes so much sense.

To think about it, the grail featured prominently in my youth. There were movies, books, murals, frescoes and even video games where it featured (not as a cup, but something hidden. Of course there was a treasure map). It always had an appeal, I just could not understand it. Maybe, for me, it acted as a gateway drug.

I wonder how damaging all the spin doctoring is on the average western psyche. But reading this, imagining myself as a dr. Jones Senior while my son comes to my study, where I am reading my books seeking gnosis. That is a nice image. Although I admit, I might divination from the image a bit and go spend some time with my kid. 🙂

To think of it, Owen Merrill makes a better dr. jones senior. 🙂

Speaking of religion, the people on Anarres call it the “religious mode”, which I guess was in the analogic philosophy of Odo. But that speaks to this separation you’ve delineated that causes such a hang up for so many people in the West.

Infallibility has the word fall in it. Something about fall from grace, fallen world, the fall of man, seems to a particular item of obsession.

“Galahad’s a great example of this. He’s the supreme Mary Sue of the Christian mystic.”

This somehow never clicked with me before, but it’s pretty obvious once you point it out.

This may sound silly, but the relationship between Percival and Galahad reminds me a lot of that between Grover and Elmo on Sesame Street: in the mid-1980’s, the young, innocent, and absolutely annoying (though YMMV) Elmo, whose main gimmick is talking in third person because of his youth and naivete, increasingly replaced the much more clever, versatile, and funny Grover, whose convoluted antics might annoy the other characters or even himself but never the viewer.

“Mary Sues as main characters make for a very specific kind of fiction, utterly compelling to readers who share the authors’ insecurities and fantasies, utterly unbearable to those who don’t. This makes them tolerably useful, in that you can very often use the response to a given Mary Sue to tell quite a bit about the person who responds.”

You answered a question I’ve been asking myself for years. Why is it that, in the Isekai genre (the Japanese genre that involves some socially inept NEET getting hit by a truck and whisked away to a D&D style fantasy land via reincarnation with his memories intact), most characters are Mary Sues?

In most cases (except the parodies), the main characters are gifted with powers so beyond the world into which they are reincarnated that they effortlessly go through life defeating enemies and acquiring fortune, fame and women. It’s “utterly unbearable” to read or watch.

Your Galahad example picture immediately reminded me of similar neutral example pictures of Joan D’Arc. And that seemed even more apropos while reading Kimberley Steele’s latest “Etheric Yin and Yang” post. It got me wondering if I’m being overly influenced by current affairs or if maybe the original authors were hinting that Galahad had a secret. Gotta go dig up Ravenscroft’s grail/blood books and see if he might have suggested that. Suddenly also wondering if he was of Druidic persuasion.

Justin, ha! And here I figured that was one more incident in the history of the Ring of Eibon.

Siliconguy, okay, that’s funny. Thank you.

Marko, no accounting for taste, I suppose. 😉 Thank you, though — I hadn’t imagined Owen Merrill played by Sean Connery.

Justin, even thinking of it as a distinctive mode is, I think, very Western. Would the analogic philosophy of Odo include a meteorological mode?

Slithy, I never watched Sesame Street, but from your comments, yeah, it sounds similar.

Dennis, I wasn’t aware of that, but yeah, it’s a good example.

Oldguytoo, nah, it’s precisely that Galahad doesn’t have a secret. He’s a manufactured attempt to insist that there’s no secret to be had.

I’m having trouble following the part about the vanishing image. The old image of the treasure was split into two portions, the secular and the sacred. The sacred gradually faded from view… and afterwards, all of the treasure’s power over people’s souls was concentrated in the secular image of money. Or in other words, if we skip past the stage in which two portions exist separately, the spiritual dimension of the treasure has become invisible, but the treasure remained as compelling as if its still-visible secular portion still had spiritual as well as material value, although those who desire it may struggle to recognise that their desire for it is not merely “economically rational”?

Whereas Wagner sought to find and reclaim the sacred portion of the treasure, drawing this power away from money towards this other image?

Do I have this right?

Suggested reading – Phyllis Ann Karr’s “Idylls of the Queen”, a meaningful and hilarious take on the Round Table from the viewpoint of Sir Kay, Arthur’s sarcastic and cynical seneschal. It’s also a murder mystery taken straight from Mallory. A lot of depth to it and eminently readable, and as a take on the Grail Quest and the Fisher King, on Morgan Le Fay, et. al, ties in quite nicely with this topic. Ace Books 1982, mass market pb.

Excellent essay JMG. This series is building up to a great conclusion!

I took a deep dive into the primary sources on the Grail legends a few years ago and I recommend this book, which compiles all of the manuscripts, including the three continuations: https://bookshop.org/p/books/the-complete-story-of-the-grail-chretien-de-troyes-perceval-and-its-continuations-nigel-bryant/11847844?ean=9781843844983&next=t

I’m still fairly ignorant about Gnosticism, and it is time to change that. My sense is that there is a lot of nonsense written about it, and it probably takes reading a number of sources to get a decent overview. What, in your view, are the best 2-3 books to start with to get an overview on Gnosticism?

Good point.

Maybe when I have shifted from Phrygian to Mixolydian I will have a better idea. Better yet if I go to Bhrupali.

Thank you for another lucid and engaging essay, JMG. You have me on the edge of my seat waiting for the next installment.

On the subject of spin doctoring, in “The Magic Arts in Celtic Britain,” Lewis Spence had a similar take on the transformations applied to the Celtic pagan sources of the Grail myth by the likes of Chrétien de Troyes, Robert de Borron, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and others.

In the older Celtic tales, the grail was alternately a cauldron, a dish, or a stone, but not a cup. Spence wrote a blistering indictment of the French and German spin doctors in his forthright Scottish style: “A good deal of nonsense has been written concerning the profundity of the Christian mysticism which inspires the Grail legend, and there can be little doubt that Tennyson, Richard Wagner and others are responsible for much of the pious glamor which hangs about it…. The pious folk who transformed the Grail legend into a Christian tradition caparisoned it with the trappings of Christian myth at a period when that was inspired by the most grovelling and absurd superstitions….”

Carl Jung’s interest in the grail legends, alchemy and gnosticism and are well documented. His lifetime of work circumambulates the idea of the Self, of which the grail, the stone, and the light of Wisdom (Sophia) are all images. He believed that humanity is confronted with the threat of a long fall into darkness unless we are able to, as you put it, “break the spell.”

As I see it, finding answers to the right questions is essential to fulfilling the central quest of our time.

I’m grateful for your presence.

Chalice versus a platter? Well, the platter that plays a part in Christianity would be the one that bore John the Baptist’s head, wouldn’t it? And a platter lacks the sexual dimension of a chalice, as the chalice is often placed near a sword. Not so with a platter.

I read Wolfram’s “Parsifal” back in the day, quite a few years ago. The part that stuck with me was his relationship with his mom, who dressed him in ridiculous clothes so he’d never become a knight, that is to say become a man. I remembered the ugly bargain bin clothes my mom used to buy for me, and that she seemed to want to discourage me from going out with girls. Although it never set me upon a grail quest, I do think Wolfram was psychologically astute about it.

The question Parsifal failed to ask has always puzzled me: How was he to know? Is this the “overwhelming question to which T.S. Eliot refers? A matter of ripeness, perhaps.

I don’t know if anyone else sees it, but your fonts ran wild!

They settled down after a while; I guess you got them under control.

@JMG #8

No argument about Galahad’s boring perfection vs. Parsifal’s interesting innocent mistakes, but was Galahad being Lancelot’s bastard a later addition and not a secret? Thanks, Drew C

A note on the Latin: according to what I was taught in school, the preposition ‘ex’ is always used with the ablative case. So ‘from among them’ would be ‘ex illis’.

‘Illas’ is in the accusative case, which takes the pronoun ‘ad’. ‘Ad illas’ would translate as ‘into their [feminine] midst’. Unless ‘ex illas’ was a common medieval (mis)usage, it makes less sense grammatically than the other interpretations you mention.

BUT if we allow the hypothesis that ‘exillas’ is a medieval misspelling of the adjective ‘exilis’ (thin, small, meagre, poor, feeble), ‘lapsit exilis’ could be translated as ‘The Poor Fallen One’, which would fit the divine Sophia pretty well. (And it reminds me of the first of the Beatitudes: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’)

‘Lapis exilis’ is also still a contender in my opinion, since ‘Worthless Stone’ is one way of referring to the common, everyday consciousness that the alchemists were toiling to transmute into the gold of enlightened consciousness. (Which reminds me of Christ saying that ‘the stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone’ – Matthew 21:42).

That is, the Grail is all around you and within you, waiting for your holy inquisitiveness to work upon it and transform it into something precious and mighty, as the simple fish platter was able to become ‘the rich grail’ that held within it the Ichtus or healing spirit of Christ.

Either way, it seems likely that Chretien was working hard to play to both his Christian and his Gnostic readers. I’d never made the Gnostic connection explicitly before, but I think you’re right that it fits the historical context rather well. Just please have mercy on us poor fallen Latin scholars whose noses have such trouble rising out of our dictionaries 🙂

I’ve long had the thought that I look forward to Wednesdays as an equivalent day to Sundays, a day of sermon. This weeks post reminds me exactly why. So many layers of meaning are wrapped up in this post, touching on our every day lives to the situation going on with the decline of the Western Empire to the possible futures we can lay seeds and work for. Thanks for continuing to provide this sacred space of sanity and finding ones center no matter what else is going on within and around us.

We’ve had 2000 Years of Priesthood And the World Is Getting Worse

Not sure where this is all going but these things seem like important clues.

The Fisher King – Is this Jesus The King of Kings and Fisher of men, who died because of a spear to the side (while being crucified)?

Is Perceval who was raised by his mother in the wilderness the son of the Fisher King?

(like how Perseus is the son of Zeus?)

Why does Sophia’s story have so much in common with Lucifer’s story?

( Does the path back to the Divine start with renunciation of arrogance, just as the beginning of wisdom starts with the recognition of your ignorance?)

Spear and Grail are pretty obviously male and female, but not sure how platter works in that metaphor.

And how this relates to getting the gold back to the Rhine maidens ??? ( I will just have to wait for the next installment. Lol)

“…the Inquisition was created to exterminate the Cathars, and only turned to other victims once the Cathars … had been wiped off the face of the earth” So the Inquisition was subject to Shirky’s Law? ;{)(https://www.ecosophia.net/a-neglected-factor-in-the-fall-of-civilizations/)

I’m not very familiar with the Percival myth, but from your description, it smells suspiciously like the ancient mysteries, especially the hero cult versions of them. (Percival seems rather reminiscent of Perseus in general; Odysseus’s mother died of grief after he set out on adventures and he abandoned a comrade with a wound which would never heal, too; etc.)

Do you know of a good English version of the early form of Percival myth? I’d be curious to add it to my list of mysteries to study…

I think it was sometime during the Lebanese Civil War that I saw a news photo of a fighter identified as Druse wearing a t-shirt with the motto “Kill Them All, God will Sort Them Out” or it may have been “. . . Let God Sort Them Out.” Needless to say, I was struck by the irony.

Rita

Daniil, yes, that’s what I was trying to suggest.

Patricia M, hmm! I’ll consider that.

Samurai_47, I hadn’t seen that complete version yet, and will have to pick up a copy. In terms of Gnosticism, Elaine Pagels’ The Gnostic Gospels is still the most widely recommended introductory book; after that, I recommend Bentley Layton’s The Gnostic Scriptures for a fine deep dive into the original texts.

Justin, then there are the Umbrellian, Galoshian, and Just-Plain-Soaked-To-The-Skinnian modes!

Goldenhawk, thank you! Yes, that’s classic Spence. He was among other things reacting to the writings of A.E. Waite, who wrote two long dull books trying with all his might to define the Galahad version of the story as the only one that counts and sweeping everything other than orthodox Christianity under every available rug.

Phutatorius, Wolfram is very psychologically astute — he’s constantly doing things like this. As for the question, it’s quite common in certain initiation rituals for the candidate to be refused on a first try due to not being able to answer a question correctly; he’s then taken around a few more times, taught some things, and then returns to the chief officer of the lodge, gives the right answer, and gets the secrets of the degree. This is one of the things that led Jessie Weston to see the Grail legend as a veiled narrative from an initiation ritual.

Teresa, there’s something funny going on with the interface between my writing program and the blog. I’ll see what I can do about it.

Drew, it was never a secret. The people who invented Galahad made him Lancelot’s illegitimate son from the beginning, and splashed it all over the stories.

Dylan, so noted! I’ll look at garblings of ille in medieval sources.

Prizm, you’re most welcome and thank you.

Justin, yes, exactly.

Dobbs, you’ll certainly have to wait for the next installment, or more precisely the next couple of installments. The Fisher King in the legends is usually an older relative of Parsifal, but the echoes of Christian legend are of course deliberate; the parallels between the stories of Sophia and Lucifer are relevant, but note that Sophia repented; and the platter (or shield) pairs with the sword, as the cup pairs with the spear. Not all polarities are sexual!

Roldy, good. Yes, exactly — having made the mistake of wiping out their primary quarry, the Inquisition then had to find somebody else to hunt down, torture, and kill. Other heretics were one option, Jews were another, but they didn’t really hit their stride again until the witch panics took off.

SDI, good. You might want to read Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance, which makes exactly this argument about the Mysteries, and my book The Ceremony of the Grail, which updates and expands on her thesis. Both Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval and Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival are readily available in English translation, and those are good places to start looking into the older version of the tale.

Rita, unfortunately that’s a way of thinking that all the Abrahamic religions fall into from time to time.

“All the old mythic images stole away from the increasingly glaring light of the conscious mind and found new homes in the darkness, where they could exercise their power unnoticed. This didn’t decrease their power, quite the contrary: it’s the mythic image you don’t recognize and therefore can’t take into account consciously that has the most power over your mind. Thus one great advantage of being mythologically literate is that you can choose the narratives you use to understand the world, instead of letting the old mythic patterns play merry hob with your mind in ways you can’t anticipate or even perceive”

Reminds me of:

“Therefore it is that you, small as you are, have your affinities with these Cosmic Beings and are influenced by their phases from the Absolute down to the atom of your own Earth, which is the Secret Wisdom. For the uninitiated man is acted upon by these forces, but the initiate, by his knowledge, escapes from their influence and uses them for his own ends.” – Cosmic Doctrine, ch 5

There seems to be something cultural with men in their early 20s where they’re more susceptible to Mary Sue literature. Maybe it has something to do with the birth at the mental sheath around 21. There’s a sort of delusional (and maybe Faustian) disregard for limits – “Let’s start a business and get rich!”. This is probably why The Kingkiller Chronicle is so popular. The main character is a total Mary Sue. I’m embarrassed to admit I really liked the series some years ago; now I look on it with wry amusement, although I’ll probably finish the the final book if it is every written. Anyway, this lack of wisdom among coming of age men seems like a lever that could be pressed magically or culturally. The closest thing I can think of right now are those conservative organizations for young people, although those come hand in hand with Christianity. I sure would have liked some coming of age initiation into a usefull way of being besides being legally allowed to buy alcohol. Maybe the natural course of things will take care of it.

Thanks for the essay! Wolfram von Eschenbach probably didn’t speak Latin himself. I mention that because “ex illas” does not exist. It would be “ex illis”.

Otherwise very interesting. Many people do seem to chase a mirage of wealth or even “independent wealth” without ever getting closer, leaving other, more important goals by the roadside.

“Kill them all, God will know his own” – I’ve never understood that attitude. It always seemed to me that you would want to keep the heretics alive as long as possible; after all, God created them and presumably wants them in heaven, so if you cut off that possibility you’re going to be held responsible for sending them to hell.

Perhaps it is just me being blinded by the narratives told from Abrahamic religions, but I can’t see how the ring can be returned without some sort of sacrifice on our behalf. People are so caught up in money, it’s hard to imagine enough people being persuaded to willingly sacrifice money, whether that be to charity or through volunteering, or other avenues.

That being said, the Covid experience did seem to encourage many to get out of the money economy and find other ways of sharing value. While the situation may prove chaotic to some extent, there is hope that it doesn’t have to be a complete upheavel, a Ragnarok or Apocalypse. Just something really close ….

I had never heard of the Story of Sophia before. I LOVE IT! We live in such Luciferian times or so i have been thinking. But what if i am wrong what if we are at the beginning of Sophia’s story rather than stuck in Lucifer’s hell.? Yeah sure we have a long hard path in front of us after we reject our hubris and arrogance. The fact that hubris and arrogance is not really working out for us makes rejecting it seems like a reasonable thing to do.

Leaving Lucifer

Seeking Sophia

Is my path forward

Hi John Michael,

Right, let’s see whether I’m getting these lessons right. Here goes:

1) Avoid Killer Rabbits and Shrubberies – death + expense;

2) Don’t attempt direct contact with deities lest the tried and true keepers become obstreperous – death;

3) Extreme personalities exhibiting equal parts: excellence; arrogance; and hubris – death (although just between you and I, I’d brave the dangers of Castle Anthrax);

4) Claims to infallibility – probably spiritual death; and

5) Disregard of entropy – foolish.

How’s my score? 🙂

Cheers

Chris

Are we going to learn more about the mysterious book, or books, used by de Troyes and von Eschenbach?

Are we in for a discussion of Eliot, perhaps my least favorite of major poets?

JMG and commentariat–

There are echoes of many themes here. Trying to prevent a son from going to war is found in the stories of the Trojan war with Thetis hiding Achilles among the women’s quarters of a friendly king.

At least one source I read while studying Arthurian fiction said that the question that Percival should have asked the Fisher King was “What ails thee, Uncle.” in other words a normal expression of concern for someone who is obviously in pain.

I wonder whether anyone in the time of Henry VIII associated his leg wound that would not heal with the myth of the Fisher King. Probably not publicly since it would have implied that the kingdom was suffering–not flattering to the ego of a ruler.

In reference to the Inquisition, it is important to remember that there was not one unified Inquisition. The crusade against the Albigensians was one. The Spanish Inquisition was directed against Jews and Moors who had converted to Christianity when the Moors were driven out but were suspected of secretly continuing to practice Judaism or Islam. The Roman Inquisition functioned only in Papal Territories (which extended into parts of Switzerland). The ruler of a territory had to invite an Inquisition, and you may note that no ruler of England ever did so. Those interested in the workings of the Roman Inquisition may find interesting material in _Witchcraft and the Papacy: an Account Drawing on the Formerly Secret Records of the Roman Inquisition_ by Rainer Decker. The Vatican opened some files to scholars a couple of decades ago. Unfortunately for historians Napolean stole many records from the Vatican when he conquered Italy, later promised to return them but never did and no one knows what happened to them.

Rita

Wow. This is very interesting. It has made me eager to read the original from Chretien de Troyes!

About the Crusade, when i was at Albi, i was told it was Bernat of Claravall who, while on a mission in 1145, was aparently scared to the marrow by the strength, establishment and maturity that Catharism was gaining in Occitanie, and wrote to the Pope and raised the alarm, giving Albi only as an example of what was going on on the whole region.

After all, Catharism put down strong roots not only among the peasantry, but among nobles as well, That’s why the Crusade turned out to be so succesful in it’s aftermath: It allowed and gave a pretext for a complete anexation, with almost all noble families in Occitanie wiped out and replaced by Normand lineages.

Unfortunately for the Cathars, Simon of Montfort turned out to be a very good leader, bold yet meticulous, who took the Castles in the region one by one, and defeated the Catalan king at Muret.

Guillem.

Teresa, the font changes hide a cryptic message. Something about the Rabbit of Caer Bannog. (That teapot idea is good enough for Monty Python!)

I read the French Arthurian literature around the time of Indiana Jones 3, which I didn’t like as much as 2 (most fans consider 2 inferior), but I loved the scene of Indy having to choose the True Grail from a shelf of false Grails. It was the one that looked like an ordinary wooden cup, such as a 1st century carpenter might have owned. There’s wisdom in that, I think. Anyway, I remember there being four Grail knights–Percival, Lancelot, Galahad, and Bors, the foreign knight. Any idea what Bors was doing in there?

Agni Yoga prefers the “stone from heaven” reading, for obvious reasons.

On lapsit exillas:

How fascinating that it clearly refers to the fall of Sophia. Why do scholars have such a difficult time making this connection? I typed the phrase into google translate and got the phrase “he slipped into exile.” Indeed, we are all spiritual beings in exile. I notice a lot of weird scholarship around Gnosticism, some modern scholars are claiming that Gnosticism as a movement did not exist, and some are now claiming that the Cathars did not actually exist but were the product of mass hysteria. What’s the deal?

On the divide between the sacred and the secular:

The division was partly a survival mechanism from early scientists. They needed to carve out a space where they could be safely allowed to work without being in danger of crossing the Church, so they divided the world into the ‘material’ and the ‘spiritual’. Then they ceded authority to the church on the spiritual and claimed authority on the material. Of course, once science gained a stronger foothold, that truce was ended and now we have materialists insisting that the spiritual and mental realms are either not real or are totally reducible to matter. Also we now have scientists paralleling the overeager clergy by claiming authority on things that they don’t have expertise in. I hope one day our culture will be able to heal and recognize the spirit in matter and the matter in spirit.

Very enlightening JMG! Because I studied French and was familiar with Chretien de Troyes, I thought I knew something about this subject….Turns out I didn’t really…Thank you for some great scholarship!

Ash Wednesday is in March, but April is still the cruellest month.

Hi JMG,

As soon as I saw the Grail mentioned I had an idea of where the post might be going. The discussion of Gnosticism and specifically The Sophia reminded me; I live in the Tokyo area and tolerably often go on long walks about the town. Imagine my surprise then when I came across a University bearing the name Sophia University. And imagine my doubletake when I learned it was a Jesuit University.

I’ve read rumors that at high levels in the Catholic hierarchy there is a willingness to engage with Gnostic ideas beyond stake-burnings. Of course most of those claims came from Protestants who I figured were engaging in the long established Christian ‘fun’ of “No, you’re the heretic!”.

But finding that school made me wonder if the Pontiff isn’t keeping things away from the unwashed after all.

Cheers,

JZ

Did you know that there are quite a few absurd little doodles in illustrated medieval manuscripts which have rabbits killing knights?

Thank you for the information on the wider Arthurian legends… all I’ve ever come across is very modern re-writings by modern authors who use the legends as a matrix on which to project their own ideal social fantasies, and versions based on Mallory’s “Mort d’Arthur”.

Now, I have a reference to go looking up the real stories.

Sometimes, in the 70s, I think, a book hit the market and turned flaming hot. It’s premise was that “the grail” was a shortened and disguised version of the original word, “sangrail” — which meant “blood”.

It’s been a while, so I’ve lost all but the gist, that the grail was actually the blood — the bloodline — of Jesus. His descendants! Basically, a line of royals anointed by the Divine. Rather changes essence of the grail stories, or maybe amplifies them.

I recall that the authors traced the bloodline to a family (wealthy) in France. They included a photo of the latest child … who looked to me like Damien of The Omen movie fame. (!)

Religious folks really didn’t like the book. For all I know, it could have been bogus history. But the idea that the old stories were really about hunting the “cup” that held what Jesus called “His blood”, is a tantalizing concept.

Hey, @samurai_47 #11 …. Thanks!

I saw “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” at the theater. I hated the ending and mostly forgot about it. Decades later I got a job working at One Eyed Jaques a store that sold card games, table top role playing games, board games, and the occasional jigsaw puzzle. At least several times every week someone would quote from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

One of the books I’m reading happens to be “The Mother of the Lord” by Margaret Barker. She makes the point that Wisdom from the book of proverbs is cast out of the temple by the Deuteronomist reformers under king Josiah.

Years ago I read the “Story of Roland” from the public library. If I recall correctly Roland was also raised in the woods by a single mother just like Parsifal.

@Marko #3

We named the dog Indiana….😉

Jake, good. Fortune was among other things a close student of Jung’s writings.

Luke, women around the same age are just as vulnerable to Mary Sues, so you may be on to something.

Aldarion, Wolfram claimed in the poem that he was illiterate, so you may be right about his lack of Latin knowledge. I’ll be looking into “ex illas.”

Roldy, if you believe in predestination — and many Christians then and now do — no, God doesn’t want them in heaven. He predestined them to fry in hell for all eternity for his own greater glory.

Prizm, we’ll get to that!

Dobbs, it’s a story with a lot of wisdom to it — pun not intended.

Chris, oh, direct contact with deities can be a good idea:

Just don’t grovel!

Mary, neither of those has any relevance to Wagner; you can certainly bring up the grail for the next fifth Wednesday, though.

Rita, there are several different grail questions — the stories vary, there as in so many other contexts.

Guillem, thanks for this.

Enjoyer, the evasion of Gnosticism is really quite weird. I’m not sure what’s behind it.

Pyrrhus, you’re welcome. It’s a very rich field of study!

Justin, doubtless because it’s tax season.

John, hmm! Maybe so.

Renaissance, okay, so the vorpal bunny of Caer Bannog goes back further than I thought.

Elk River, the title is Holy Blood, Holy Grail and it was impressively bogus. That “Sangreal” might have been “sang real,” “royal blood,” is an intriguing notion nonetheless.

Moonwolf8, I grew up in a circle of teen geeks who all adored the movie and could quote entire scenes from memory. Still, I understand not liking the ending.

” Anyway, this lack of wisdom among coming of age men seems like a lever that could be pressed magically or culturally. The closest thing I can think of right now are those conservative organizations for young people, although those come hand in hand with Christianity. I sure would have liked some coming of age initiation into a usefull way of being besides being legally allowed to buy alcohol. Maybe the natural course of things will take care of it.”

You are overlooking a traditional one.

Feb 5 news “WASHINGTON (NewsNation) — The U.S. Army announced its record-breaking recruitment numbers, marking its most productive December in over a decade, with some crediting President Donald Trump for the boost.

This marks a significant turnaround for the branch, which has faced challenges in recent years in recruiting enough young people and has implemented major changes to its recruitment programs.”

Feb 25

“The Air Force and Space Force are currently on track to meet their fiscal 2025 recruiting goals, the Department of the Air Force’s top recruiting official said, keeping up a hot streak after several challenging years.

“All components [of the Air Force] and the Space Force are either on or ahead of their curve for where we should be this time in the year,”

“MILLINGTON, Tenn. (October 1, 2024) – The U.S. Navy exceeded its Fiscal Year 2024 recruiting goals, contracting 40,978 new recruits by the end of the fiscal year and marking its most significant recruiting achievement in 20 years.”

Stop insulting the people you want to work for you and wonderful things happen.

Boot camp definitely counts as an initiation.

@blue sun

I have a lot of fond memories of that dog. 🤓😉

@JMG

Oh 😯 Sean Connery would work well for Owen. An I shall refrain from speculating on the actors for the other characters. Not to degenerate into fanboy speculation.

As for my taste, I have noticed; 1 it always was strange, 2 it seems to be evolving.

1 I spent a lot of my youth in stories and media. A lot. Most of the early stuff was on par with Indiana Jones. Looking back I sometimes think it was necessary for me at the time. Like how a young chick’s digestive system needs protein, but an adult chicken eats mostly plant matter. I lived in a mythologically illiterate society. I kind of think it was perhaps necessary for my growth.

2. I have noticed that my taste seem to be evolving and the reason seems to be understanding. I never liked opera, until last year. And I notice, that I notice more meanings and connections in works of art, and in my environment.

So there might be some hope for me yet.

That was quite an entertaining account of the origins of the grail legend. I would never have known any of it if I hadn’t read it here. I would have just continued to believe the version proferred us in the movie “Excalibur,” and some references in T.H. White’s The Once and Future King.

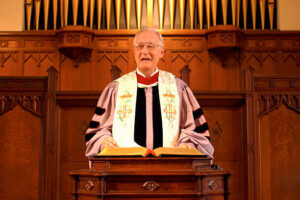

Discussing Wagner takes me into deeper philosophical waters than I wish to hazard just now, let alone discussing the ideas of C.G. Jung. So I’ll comment on the paintings.

Galahad looks gay. I love his nelly fourteenth century armor. But to judge from the very slender right leg, his lower body seems less robust than would be called for in a warrior. I hope Christian mystics won’t get too upset with me for making such impious observations.

The image of Percival looks like a fine Pre-Raphaelite painting. Do you happen to know who it’s by? I love the deep rich colors, and good drawing ✍️ is always a pleasure to look at.

I am attracted to the idea of a sun treasure; it tends to make me think of chests of pirate gold catching sunbeams on the sea bottom. Perhaps I’m caught between the spiritual and materialist conceptions of the great treasure.

Is it generally thought by scholars that the Fisher King has some Christian symbolism? I seem to recall that Jesus has been described as a fisher of men (or was that Peter, an actual fisherman?), and the spear seems suggestive of the one that killed Christ. Since Chrétien de Troyes predeceased the resolution of his story, I guess the fisher king will never be healed of his wound. Poor fellow!

As usual, I learned a lot from this essay — thank you! I wonder what you think about the extent of Buddhist influences on Parsifal — via Schopenhauer or directly. It’s no secret that Wagner toyed for years (decades?) with the idea of yet one more opera, tentatively called The Seekers, based on an incident in the life of the Buddha and involving a woman who succeeds in convincing the Awakened One that she need not be reborn as a man before she can contemplate entry into nirvana. He never wrote it, of course, and am I correct that he concluded that he had said all he had to say on the subject in Parsifal? (It is compassion — compassion for Amfortas. — after all that keeps Parsifal from succumbing to Kundry’s wiles. If that isn’t a Buddhist notion, I don’t know what is.).. Instead of repeating much of what he had said in Parsifal in another opera, so I gather, Wagner was contemplating writing symphonies in his final years, But alas, he died before he could start in on them.

Hi John Michael,

Like you, I tend to view money as a tool, so when you wrote about money being symbolic I was a bit lost. Symbolism is not my strong suit. However, trust me in this, I can well see the lure of the stuff in my casual observations, and we’ve spoken of this over the past few weeks.

Out of curiosity, what do you reckon it will take to break that spell?

Cheers

Chris

Hi John Michael,

Oops! Forgot to mention, yes I won’t grovel. 🙂 I too was one of those geeks. What a fun film, but you can sort of see the narrative tension which came from having two directors. The Life of Brian (which is also a film I love) was far more cohesive in many ways. Man, that scene with the centurion correcting Brian’s Latin grammar was hysterical. Far out. Just have to re-watch it now and for sure the silliness will haunt my dreams.

Cheers

Chris

This brings back memories. I did my history thesis on Cathar architecture. I came across an essay written in the early 1900s in German that I made a clumsy attempt to translate (way before Goggle translate) that made the case that a certain style of church in the south of France contemporary to the Cathars exhibited characteristics antagonistic to the Gothic that was spreading from the north. It’s hard to see now but the north of France (really just the Ile-de-France) was another world to the south. The south had their own language, religion and, for my thesis, architecture. All of that was destroyed in the Cathar Wars. The version of orthodoxy pushed from its center in northern France was also the same orthodoxy that silenced the Celtic version of Christianity. Many threads.

As to architecture, there are many churches spread across the present day departments just north of the Pyrenees. Their common characteristics are the Greek cross instead of the Latin cross, a tendency toward the use of domes and semicircular arches (as counterpoint to the lancet arches and vaulting of the gothic) and a general centered-ness that implies the circle. My thesis was that the Greek cross and the dome were significant as items that would have been brought back from the holy lands by the Crusaders supposedly alongside Catharism. The dome was significant because it represented the circle as a juxtaposition to the cross. I don’t think I made the case well but the idea of heretical architecture intrigued me.

Anyway, I haven’t thought about this stuff in decades. It was all caught up in a current in the late nineties with the DaVinci Code. Some odd books came out around that time. I’ve read and reread the reprints of Otto Rahn whose mysterious death deserves a movie. Another favorite was by Jean Markale that wove a beautifully bizarre web around a certain village in the Aude and a Cathar castle called Montsegur. These interesting books were interspersed with the “scholarly” ones that said the Cathars didn’t exist or that they did exist but were just proto-Marxism. So it goes.

I’ve read the old grail stories and had heard of Wagner’s Parsifal but this new perspective is fascinating. Thanks as always for the enlightening journey!

No doubt. I re-read Eliot’s Wasteland yet again last night. There are some strikingly vivid passages and imagery, but other parts are as impenetrable as the tax mans code.

Speaking of Sophia, do you think the Pistis Sophia -or some similar gnostic text- might at all have been the book that both Troyes and Eschenbach spoke of that the scholars dismissed out of hand? There must have been some surviving copies of such things.

On another note, how do you think groups like the UGC, and other gnostic lineages -and the broader spectrum of occult orders in general, that often have priesthoods- can sidestep or walk around that boulder in the path, that you have sketched out, with regards to this problem of claiming “infallible access to the will of the Divine.” Obviously the specialists in other cultures that you mention don’t have that attitude, so looking to them would be a start.

I ask because I’m aware of some gnostic types who have taken to wearing a collar like a priest or vicar as they go about in society, as a way of setting them apart, and to my mind, making them feel special. To each their own, live and let live, but I didn’t really care for that anymore than I liked the idea of the way neopagans have whined about needing to have their own special clergy.

I also ask because the puffed up-ness, (or “egoizing” as the Odonians might have it) is a major turn off for many people who might otherwise use the tools covered under the umbrella of religion. They’ve heard too many preachers rant and rave, and then be tore down by their sexual escapades, or what have you. So the the good aspects of meteoreligion get dismissed.

Siliconguy, and of course the military is also the traditional way for young men from poor backgrounds to get an education and career training, so the initiatory aspects fit rather nicely into the old custom of trade guilds and the like.

Marko, fortunately it’s all idle speculation, as there’s zero chance any of my tentacle fiction will ever appear in movie form. As for your taste, good to hear that it’s evolving. That’s true of most people who really care about books, movies, etc. — there are things I adored in my teen years, for example, that I can’t even read now.

Kevin, I simply went hunting online via image searches — the Perceval is one of the images that came up from the search string “Perceval Grail,” and the Galahad was the most suitable response to “Galahad Grail.” I agree that Galahad looks like a wimp!

Tag, the draft of an opera was Die Sieger, “The Victors,” and as far as I know Wagner scholars generally agree that a lot of it ended up in Parsifal. Wagner studied Buddhism fairly intensively in the 1850s — like a lot of early European students of Buddhism, he was originally attracted to it via Schopenhauer, but went to translated Buddhist texts and scholarly works on the faith, since there were plenty of those available in translation by that time. I wish Wagner had gone ahead and written it — it was an interesting story and I think he could have done good things with it.

Chris, what will it take to break the spell of money? The fall of our civilization. I don’t know of anything else that’s done the trick. As for that scene in The Life of Brian, oh, yeah. It’s one of the best parts of a very, very funny movie.

Daniel, fascinating. Is your thesis available anywhere? It would be useful to me in some of my current studies — among other things, I note that the church architecture of the Knights Templar also tended to emphasize circular structures. Here’s Temple Church in London, for example:

Justin, hmm! It’s a fave of mine, and penetrable if you know the contexts. As for the book, no, both Chrétien and Wolfram say that it’s a book that recounts the Grail legend specifically. Wolfram says that it was written by Kyot de Provins, based on a work by the heathen philosopher Flegetanis. There’s been a vast amount of scholarly handwaving about those names, but the basic concept remains plausible.

With regard to the broader question, it’s always a struggle. One of the reasons I stopped taking students for UGC ordination a good many years ago, and only started up again recently, was that so many of the people who came to me wanting ordination were just looking for some way to claim unearned authority over other people, which is inherent in our culture’s notion of priesthood but is antithetical to the UGC tradition. I’m sorry to say there’s no shortage of Gnostic priests out there who’ve fallen into the same trap. It may be futile for me to fight against it, but there it is: I’m not interested in helping another round of little tin gods inflate their egos to the bursting point. Even more, that’s not what the UGC is about, and I care enough about the tradition that I don’t want to see it twisted into its opposite.

On the case always governed by the preposition “ex,” Dylan is right, and his further interpretative suggestions seem plausible to me.

I have not been able to find a source for the form in which JMG cites this phrase, “lapsit exillas.” An online text of Wolfram von Eschenbach (apparently hosted by Notre Dame University) has “lapis exilis” while acknowledging that “lapsit exillis” is a variant found in some MSS. The latter, of course, meets Dylan’s objection satisfactorily.

See note 24:

https://www3.nd.edu/~gantho/anth164-353/notesParzival.html#n24

Most societies around the world and throughout history haven’t drawn a hard and fast line between the sacred and the secular. The two interpenetrate so completely that many of the world’s languages have no word for “religion.” This isn’t because there’s a shortage of activities of the kind we call “religious.” It’s because the people who speak these languages had no need to separate them out from all other human activities.

According to Norman Cantor, Europe did not divide the sacred from the secular until about the time the first Parsival was written. (1066 and Manzikert and all that meant fewer raiders from outside western Europe, so more wealth, so the difference between Catholic Church law and secular law had enough money involved to be important).

Wait! Does this mean that George Lucas stole from Perceval when he wrote Star Wars: Episode One? When he had a young Anakin Skywalker ask if Padme was an angel? Or how his broken hearted mother died when he left? (Though admittedly , this was due to an acute case of Tusken Raider torture). That’s where the similarities end as far as I know but it is an interesting coincidence. I don’t the think the word “angel” is used anywhere else in the entire film series also it really sticks out in the first episode.

JMG, I thought you might enjoy this synchronicity… I have been reading through your past Magic Mondays and happened to run across the following not long after reading the current essay ( https://ecosophia.dreamwidth.org/26061.html?thread=1315021#cmt1315021 ). Sounds like you’ve had this project brewing in your mind for some time!

Did you know that there is one theory that the Arthur legend is actually based on of the kings of the Lombards in Italy?

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authari

And because the Saxons actually participated in the initial Lombard invasion of Italy in 568, some of them took the stories they heard there to their kin who were settling Britannia. I can give you more details on the similarities if you are interested.

Whom does the Grail serve? “The Grail serves the servants of creation…”

I don’t remember where I read that, but it’s “served” as an interesting meditation subject for me. If one imagines the Grail as holding CONSCIOUSNESS itself, it’s a support for the dual substance (as opposed to non-dual) theories of mind and consciousness as presented in Patanjali yoga world view and pedagogy.

Summary: the body, mind and senses are an inanimate machines “turned on” by consciousness. Classical Yoga psychology and practice proceed by cleaning up the machines in order to “find the grail” – the light of pure consciousness. This not only opens up the reality of one’s own true powerful identity, but also opens up possibilities of communication between “minds” on all levels of existence.

Dualism is not everyone’s cup of tea for sure😉

However, it’s a world view that’s “served me well” (as a servant of creation)!

JMG -your essay was amazing.

Another breakthrough for me when reading it was the bit about mythic images finding new homes in the darkness. I think one of the greatest gifts of the Tarot and it’s study is how it can bring buried narratives and patterns to light so that their power can be wholesomely integrated.

Thank you again and always.

Yogaandthetarot Jill C

I know I could unpack more of Eliot’s poem if I put some more time into it.

Re: UGC … Sounds good, thank you. I appreciate your efforts…

—

In the meantime I found these Orphic Sayings of Amos Branson Alcott… some real gems in there, like this one on the ides of sin, which seems rather gnostic, and relates I think to this conversation: “All sin is original,—there is none other; and so all atonement for sin. God’s method is neither mediatorial nor vicarious; and the soul is nor saved nor judged by proxy,—she saves or dooms herself. Piety is unconscious, vascular, vital,—like breathing it is, and is because it is. None can respire for another, none sin or atone for another’s sin. Redemption is a personal, private act.”

I do think there can be good in confessing to another person -but that person doesn’t have to be a priest, and isn’t the sole connection to the divine. But rather, the act of confessing helps clear your conscience and hopefully make better choices in the future. What adam & eve did in the garden seems to have little to do with it either.

I have been listening to a series of lectures on the transcendentalists, by Ashton Nichols. I found the lectures on William Ellery Channing, and certain aspects of the one on Theodore Parker, to be filled with ideas applicable today -though I wouldn’t call myself a unitarian. But I see in them a connection or lineage to various types of religious dissenters … which is of course why so many people came here in the first place.

All this talk of the bloodthirsty bunny of Caer Bannog and doodles of knights in mortal combat with rabbits has me looking askance at our pet rabbit – who, I might add, has been identified by fellow fans of ‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’ to have a striking resemblance to that dreaded beast (a descendant, perhaps?). She has nibbled each family member at least a few times in the past (but not in the bum) and so I wonder if she is just tasting her prey before deciding whether or not to devouring us in the middle of the night? I will advise my son to lock her cage door before he goes to sleep, just to be on the safe side…

With or without Wagner, it is good to see some posts by you on this enduring (and nearly twisted out of recognition) legend. My main ‘scholarship’ on the topic consists of watching the Monty Python movie at least 40 times during my youth, and a single reading of Mort d’Arthur at the age of 20. Though I have an enduring fascination with the myth I have not bothered to delve into reading any books about it because I figure that 19 books out of 20 are balderdash and I’d rather spend my time on a less mine-filled field. So, thanks for getting the discussion going; looking forward to what comes next!

Of late, it has become a massive political pain point for the Hindu community in India that we do not have a word for religion, nor have our scriptures ever used such a word.

You see, the fathers of the Indian constitution copied large sections from older British administrative law, and from American, Swiss, and Soviet constitutions. This means our constitutional law protects religious rights of citizens, but defines those rights in ways that only make sense if your scripture explicitly distinguishes between religious and secular aspects of life.

While Christian missionaries and Muslim denizens gain massive benefits from these protections, Hindu groups repeatedly find their religious issues being deemed secular, cultural, or even customary, by their own country’s government. The recent issue of women’s entry into the sanctum sanctorum of the Lord Aiyappa temple, for instance, brought this discrepancy to light.

Lord Aiyappa is a deity who, by legend, has vowed chastity. Women are not allowed into the sanctum sanctorum of his temple. A group of “feminists” decided that this was a human rights issue of exclusion, and demanded entry of women into that room.

Needless to say, practicing Hindu women would respect the celibacy of the deity and not enter the chamber, while atheists and non-hindus have little-to-no business being in the heart of a Hindu temple to begin with. But with no clear dogma or creed, the only basis for classifying a person as hindu is jus sanguina: if their parents are registered as hindu, then they are registered as hindu regardless of whether they practice or not. This practice, if course, was initiated by our English overlords in the heyday of their occupation.

This little loophole allowed all manner of irreverant crud to force entry into the sanctum sanctorum or the deity in the name of Women’s Rights. Newspapers that print in English, needless to say, supported them completely. The priesthood was duly portrayed as a bunch of insufferable patriarchical ignoramuses. Any argument in favour of the faith and its policy were dismissed as medieval and unjustifiable.

It took a mammoth effort on part of a team of dedicated legal professionals and cultural activists, spearheaded by a brilliant attorney named J. Sai Deepak, to finally force the government to regard the policy of the temple as a valid instance of religious doctrine, protected by constitutional law. Years of legal battles later, the court finally ceded the case to the Hindu community, and to this day there are leftists and “progressives” who claim it to be an instance of Hindu majoritarian despotism.

@ ambrose #35

Really? Not that I can see but then I’m terrible at codes.

Why don’t scholars (or anyone) refuse to see what’s right in front of them?

Because it conflicts with their upbringing, training, world view, and what their friends and professional colleagues believe.

I’m currently plowing through “War Before Civilization” by Lawrence H. Keeley (1996, Oxford University Press) and in the preface, he discusses how archeologists — including himself!!!! — simply refused to see the heaps of bones they’d uncover with arrowheads embedded in them and the obvious fortresses they’d unearth as being evidence of violence and widespread fighting.

Professor Keeley came to understand differently, as he began to observe and not just look.

The lure of happy, peaceful, Rousseau-like Neolithic pastorals was just too strong.

That could be what’s happening here, with Sophia.

Gray Hat, interesting. It’s always possible that I got it wrong, because lapsit exillis would indeed meet the objection.

Bruce, that sounds about right.

Paul, I have indeed. I’ve been pondering it since I first read Wagner’s essay “Die Wibelungen,” which is quite some years ago now.

David, no, I hadn’t run across that theory yet. The Arthurian legend isn’t as good at generating oddball theories than the Atlantis legend, but it’s good to see that it’s catching up.

Jill, that’s quite a bit of meditation fodder there! Thank you.

Justin, the Transcendentalists don’t get enough attention in today’s alternative-spirituality scene. I intend to find some good material for the UGC lectionary from that source.

Ron, I didn’t watch the movie in question quite so often, but it’s more or less engraved in my mind. Since I was your classic autistic geeky bookworm back then, though, I balanced it by reading every scrap of medieval Grail literature I could get!

Rajarshi, ouch. Do you think there’s any chance that some competent pandits and lawyers could work together to work out some kind of theory of religious Hinduism that could pass legal muster, and safeguard the religious rights of devout Hindus?

Teresa, that’s a classic example. The way that the Mayans were misdefined in the same way, until the Mayan hieroglyphs were deciphered and it became immediately clear that Mayan city-states fought each other tolerably often, is another. There are many more. Scholarship is less immune from groupthink than most other human activities!

Hmmmm Money as archetypal sun treasure explains a lot about the rise of our current billionairocracy in the Western world

Fantastic to hear about the lectionary…re: Transcendentalists…

…I plan on writing about some of these people. I’m looking to incorporate some of their other ideas into other things I’m working on too.

Cheers to all.

>“Kill them all, God will know his own” – I’ve never understood that attitude

If I were that deity, as soon as the guy who did all the killing died and crossed over into the afterlife, I’d take him right back to that point in time and say “You sort them out now, take your time but you don’t leave here until you do” and then walk away.

I mean, I wouldn’t dream of being God but I wouldn’t appreciate people intentionally creating messes for me to clean up. Would you?

>the military is also the traditional way for young men from poor backgrounds to get an education and career training, so the initiatory aspects fit rather nicely into the old custom of trade guilds and the like

Whether you’re poor or not – infantry is a skilled trade, just as much a skilled trade as HVAC or farming or auto repair or plumbing. I think the minimum cutoff IQ for infantry is 100?

Re: Domed Heretical Architecture

I dug out the old thesis and my memory was fuzzy on it. Looks like most of the southern French churches still stuck to the basilica plan but with domes along with some other unusual features that more mimicked architecture from Byzantium and further east. There is still a distinct focus that differs remarkably from the Gothic that strikes me as very foreign to the growing orthodoxy of the age. Despite the distance from the version of me that did the writing it is still readable though the argument is tenuous. Appropriate for a undergrad history thesis. Rereading it I wish, as my professor did at the time, that I could have spent some time in person in the churches I described. But the history department at my university was way down the list from the football team so we had negative funding.

The digital version is undoubtedly long gone or on a hard drive that no longer spins. I do have a hard copy that I could lend you if only for the bibliography. I can send it along with a prepaid return label if you wish. Feel free to email me.

Hi John Michael,

Given the Norman invasion of Britain way back when, just from a purely pragmatic perspective, I kind of wonder if the sudden interest in Arthurian stories a few years later, particularly from what looks like authors with French names, don’t you reckon that there is a historical political element to the arc of the narrative?

And yet what interests me the most was that as a character and story, Arthur was both before and after, if you know what I mean.

Cheers

Chris

SDI/#22 — SDI, a totally fun, low brow way of reading what appears to me to be the Parcival story based on Eschenbach from these essays — is Parcifal’s Page by Gerald Morris.

Thank you for this, another interesting essay. And a good summary of a fascinating myth, even if I’d already read up a bit on those details in part due to inspiration from your Druid Revival books. I don’t really have a proper argument here, just a few stray observations:

It’s intriguing to me that this story hinges on the hero failing because he follows the instructions he’s given and doesn’t speak out of turn. In most tales like this, it’s the other way around: failure often comes as a result of not listening to wise counsel, or by disrespecting a powerful and maybe semi-divine figure. Here Percival does the prudent thing and listens, and that causes him to fail. That’s a neat inversion.

I meant to say this last time and didn’t get around to it in time, but I find it interesting how Wagner apparently was able to predict neoliberalism 150 years ahead of time. Maybe it wouldn’t have been that hard to extrapolate from the commodification that existed in his time, but considering what absurd extremes we’ve taken it to (“ecosystem services”, anyone?), I still think that’s a noteworthy feat. Also, if money and the Grail are the solar treasure, where’s the telluric counterpart?

Speaking of which, my favorite interpretation of the Grail is the one in the Druid Magic Handbook. It’s just such a beautiful image, and makes a lot of sense to me.

In any case, looking forward to seeing Wagner’s solution when we get there. Along with commodification, we’ve also taken quantification in general to extremes, so maybe that’s another part of the puzzle…

@ Luke Z #26