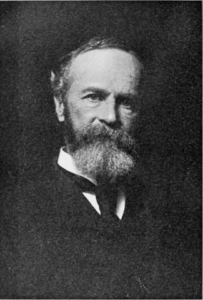

Recently I’ve been reading the writings of the American philosopher William James. You won’t see much discussion of his work among philosophers nowadays, and that’s not just because he happened to be white and male. He had the bad luck to reach maturity as Western philosophy was in its death throes, and he added to that misfortune by having a mind clear and honest enough that he drew certain necessary conclusions from the intellectual struggles of his day.

He hasn’t yet been forgiven for those conclusions. There are reasons for that—understandable reasons, though not good ones. The conclusions, and the reasons they’ve been ignored, have lost none of their relevance since his time. Quite the contrary, the harsh conditions tightening their grip on our industrial civilization just now can’t really be understood without listening to what James and others like him were trying to say, and what those who denounced him were trying even harder not to hear. Thus we’re going to have to talk a little about the history of philosophy.

Yes, I know perfectly well that most people think of that subject, on the rare occasions that they think of it at all, as the dullest sort of useless academic trivia. They’re wrong, but there’s a lesson in the mistake. The next time Neil deGrasse Tyson throws one of his public hissy fits insisting that philosophy is just plain wrongety-wrong-wrong-wrong, I hope none of my readers are so slow on the uptake as to think this shows that philosophy doesn’t matter. Quite the contrary, he’s so petulant about philosophy precisely because it does matter, and he’s got his eyes scrunched shut and his hands over his ears, shouting “La, la, la, I can’t hear you” at the top of his lungs in a vain attempt to ignore the message that philosophy is gently trying to murmur to him.

The same is true of the general public, if on a rather milder way. Seventy years ago, the publication of a new book by Jean-Paul Sartre or any of the other well-known philosophers of the time was a media event, the kind of thing that spawned articles in the arts and culture section of daily papers in dozens of cities and sparked cocktail-party chatter for months. That happened because the things Sartre and his fellow philosophers were talking about mattered to most people. That was then, of course. Since that time, philosophers and the general public have worked out a tacit agreement: the philosophers make sure to say nothing of interest to anyone outside their own little academic coteries, and the general public responds by ignoring them completely. All this makes it easy for both sides to pretend that an earlier generation of philosophers didn’t cut the ground right out from under their feet.

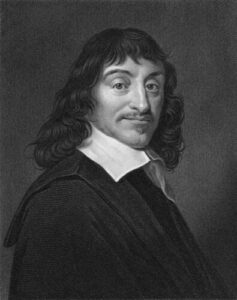

We can begin the story with René Descartes. He launched modern philosophy by trying to figure out what can be known for certain by the human mind. That’s where his famous dictum “I think, therefore I am” came from: having set out to doubt everything, he concluded that there had to be somebody doing the doubting. Now of course his version of what the mind can know included most of the standard beliefs of his time and culture, partly because doubting everything is a good deal harder than he realized, and partly because doubting the wrong things in 17th-century France could have landed him in prison or worse. What mattered was that he made a start.

That beginning was taken up and carried much further by a series of brilliant philosophers, of whom John Locke, George Berkeley, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant were the most important. All of these pursued the same question—what can the human mind really know through its own powers?—with increasing clarity and rigor. The endpoint of that trajectory was reached by Kant, whose Critique of Pure Reason showed that the human mind can only know what it creates.

Let’s walk through a bit of his reasoning. When you see an object—say, a cup of tea—what actually happens? You experience a series of disconnected sensations of color and shape; one part of your mind assembles those into an image, and another part of your mind assigns a label to that image: “teacup.” Without those processes of assemblage and labeling the world would be, in James’ useful phrase, nothing but “a blooming, buzzing confusion” of unconnected sensations. Try to follow the individual sensations back toward the object and you run into even more obstacles. How much does the image in your mind have in common with the game of electrochemical hopscotch in your optic nerve, how much information do the dancing electrons of the retina pass on from the antics of photons that spray through the eye, and how much does a splash pattern among photons really tell you about the quantum probability cloud of electrons that deflected those photons and set the process in motion?

Kant lived long before quantum theory, of course, but he got to many of the same conclusions well in advance by sheer ruthless logic. He even showed that space and time as we experience them are products of human consciousness, not “out there” in the world. There are doubtless things analogous to space and time in what he called the Ding an sich, the “thing in itself,” but we don’t know anything about them, and as the quantum physicists showed later on, they routinely behave in ways that make hash of our notions of the way space and time work. Thus we cannot know the world directly. All we can know is a model of that world assembled by our minds and nervous systems. That model is good enough for the purposes of everyday life and it can be leveraged in clever ways by scientists, but it can never tell us the truth about the world.

That was the discovery that rattled the foundations of eighteenth-century Europe. If Kant and his contemporaries had known enough about the history of philosophy elsewhere, they would have realized that this is something that happens to every philosophical tradition. All philosophy starts out with the naïve conviction that it’s possible for the human mind to know the truth about the world, and then runs face first into the same realization that staggered Kant’s readers. After a period of flailing, mature philosophical traditions reorient themselves by recognizing that if the mind can’t know the world directly, it can at least do a better job of getting to know its own creations. That’s where you get the great syntheses of Classical, Hindu, and Chinese philosophy, which present a set of more or less useful models about nature but go on to place the healthy unfoldment of individual or collective humanity at the center of the philosophical enterprise.

That was the direction that William James chose: to recognize that the human mind can give us only a rough approximation of the realities around us, and to focus instead about what we can actually know. That was the basis of his philosophy, which he called Pragmatism. There are other options along the same lines. Sartre, whose name I invoked a moment ago, did the same thing in his own way; so did Schopenhauer, and so did some others. Most philosophers in the Western world after Kant, however, rejected that path and set out instead to find some way to insist that Kant was wrong and the human mind really can know the truth about the world.

The quest for an answer to Kant fell broadly into two broad overlapping phases. The first, which had its peak in the 19th century, took its keynote from Hegel, who simply insisted that the mind had something called “intellectual intuition” which enabled it to do an end run around Kant’s challenge. That didn’t work very well, not least because no two philosophers seemed to be able to get the same results with their “intellectual intuition.” That difficulty led most later thinkers to interpret Hegel’s phrase as meaning something much closer to “brain fart.”

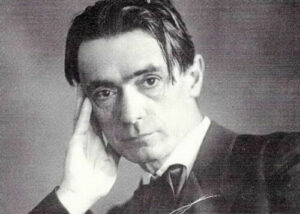

Despite the joke, this wasn’t a light matter. European thought inherited from its Christian roots the idea that knowing the truth about the world was a matter far more serious than mere life and death. That was why Friedrich Nietzsche—another thinker who took Kant’s insight seriously—wrote mordantly about the chaos set in motion by the collapse of the idea that the world known by the mind is the real world. That was also why Rudolf Steiner, whose ideas we’ll be discussing in future posts, launched his career with a volume, The Philosophy of Freedom, in which he tried to prove that thinking really could grasp the objective truth about the world. It was a gallant attempt, and he carried it out about as well as anyone could have done, but it didn’t work. He had the good sense to turn in other directions thereafter.

The failure of this first phase made the second phase inevitable, and set it going along its own foredoomed course. This peaked in the 20th century, and was based on the loud insistence that Kant’s insights don’t matter, so shut up, philosophers! That’s the intellectual current to which Neil deGrasse Tyson belongs, for example, in his angry claim that philosophy must be bad because it doesn’t justify his blind faith in the predestined march of science toward universal omniscience. More generally, it’s the current that gave rise to the modern managerial state.

The problem faced by this latter phase, in turn, is quite simply that the issues Kant described don’t go away just because you refuse to think about them. If you recognize the hard limits on our minds’ capacity to know reality, understand that our ideas can only be a rough model of the world as it is, and act accordingly, you can come up with workarounds for the bad habits of human thought and avoid many pitfalls. If instead you insist that the world is whatever the human mind says it is, and flee from philosophic insight into an increasingly shrill insistence that the mind’s truth is more true than the events it claims to describe, you end up in a world of hurt.

That, in turn, is where we are right now.

Look around you, dear reader, and notice how many of crises in today’s industrial societies unfold from somebody’s insistence that a concept they’ve fastened onto something is the absolute objective truth about that thing. I could doubtless provoke screaming tantrums in this post’s comment section by citing examples from either side of the political spectrum just now, but I don’t find that particularly entertaining, or for that matter particularly useful. All you have to do is look for what Korzybski called the “is of identity”—“this is that”—and watch the fur fly.

There’s a potent historical reason for this. During the first half of the twentieth century, most of the world’s industrial nations ended up being run by a managerial elite that claimed the right to rule on the basis of their allegedly superior understanding of the way the world works—and the “superior understanding” in question was based on a knowledge of abstractions. That process began in 1917 with the Russian Revolution and ended in 1945 with the imposition of technocratic governments all across conquered Europe and Japan; the beginning of Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in 1933 is a good start date for the process here in the United States.

That transfer of power was justified, or at least excused, by the claim that handing society over to cadres of university-trained experts would be ever so much more efficient than leaving it in the hands of the former ruling classes. Did that work out? In the short term, yes: some obvious abuses got taken care of, some programs that benefited ordinary people were enacted, and the problems caused by allowing too much wealth to be hoarded by the kleptocrats of the former elite were fixed by forced expropriation and redistribution of excess wealth, using expedients that ranged from high tax rates in the United States to mass murder in the Soviet Union.

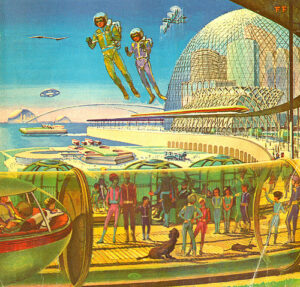

That’s pretty much what every newly arrived ruling class does, and it always works tolerably well. It’s what happens afterward that matters, however. The new managerial elite made quite a range of confident claims about the wonderful world that would surely arrive as soon as it finished clearing away the detritus of the past and put its program of expert governance into effect. How well did it work? Well, try taking a look out the window. If you don’t see sparkling domed cities from which poverty and disease have long since been eliminated, flying cars zooming overhead while a daily flight to the Moon takes off from the local spaceport, and a nuclear power plant somewhere nearby turning out electricity too cheap to meter, let’s just say that the promises sounded great but the followthrough left a lot to be desired.

The difficulty in the way of that shining mirage was the same one that Kant analyzed in theory and James among others explored in practice. It’s one thing to manipulate abstract concepts and make a nice pretty picture out of them, and quite another to make realities in the grubby world of fact behave the way that the concepts do. Flying cars, space travel, and nuclear power all looked great on paper, but all three of them shared a common flaw: the value that each of them provided turned out in practice to be too small to justify their enormous costs. That prosaic reality never found their way into all those glossy portrayals of the world of the future that saturated the corporate media back in the day, but that didn’t make those or many other similarly unwelcome facts go away. We live in a world shaped by the tremendous failures that resulted.

Charles Fort pointed out many years ago that the prestige of science depends on a slick public-relations scheme whereby every success is trumpeted to the skies while every failure is swept under the nearest available rug. The same is true of the prestige of the managerial classes in today’s world. These days, their predictions and projects fail far more often than they succeed, but the corporate media can be counted on to yell all day and night about their successes and pretend that the failures never happened. There are plenty of reasons why so few people these days believe anything that comes from official channels, but that’s one of the big ones.

The logic behind this self-defeating habit is that our managerial aristocrats can’t simply step away from the claim that their mastery of abstractions gives them superior insight into the world of everyday affairs. That claim is what justifies their present condition of privilege, but it’s also the foundation of their collective identity. Like so many people cornered by the consequences of their own errors, accordingly, the managerial class has reacted to its failures reacted by doubling down. That’s why so much of the rhetoric that comes out of official sources these days consists of angry demands that everyone else has to agree that up is down, sideways is straight ahead, and if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, don’t you dare suggest that it might be a duck!

That’s the usual way that managerial castes deal with the mismatch between their preferred abstractions and the annoyingly contrary behavior of the world we experience. It’s also the usual way that managerial castes crash and burn. To begin with, insisting that abstractions are correct even when the facts don’t bear them out is a great way to drive the society you run straight into the ground. But there’s another difficulty. If there’s a conflict between the abstractions you prefer and the facts you encounter, and all your training (to say nothing of your class privilege) predisposes you to believe abstractions instead of facts, it becomes very tempting to treat belief in the abstractions and denial of the facts as a loyalty test for your subordinates.

This temptation becomes especially strong if you’re haunted by a suspicion that the abstractions are wrong and the facts are right, but can’t admit that to yourself. That’s when the psychology of previous investment comes into play, and you start demanding that other people believe in order to shore up your own flagging faith. Nor does a single act of faith ever do the job. The worse things get and the more obviously failure stares you in the face, the more likely you are to demand even more extravagant proofs of loyalty from those around you, and the result is that you expect people to believe a series of ever more preposterous claims in defiance of everything that’s happening around them. In due time you end up living in a dreamworld defined wholly by your own absurd demands for blind faith in abstract impossibilities—and it’s at that point, by and large, that the facts break down the door.

We’re probably not far from that stage just now. Turn on the media, if you can stomach it, and you can count on getting an earful of abstractions serenely detached from the grubby realities they claim to represent. When “safe” means “it kills people,” “effective” means “it doesn’t work,” and “the situation is under control” means “all our predictions turned out to be wrong and we have no idea what to do,” you’re looking at a ruling class that’s got a great big concrete wall across the road ahead and the accelerator slammed flat against the floor.

It’s a little late in the day to suggest that they might want to slow down a bit, read some William James, and grapple with the fact that the buzzing, blooming confusion of the universe is under no compulsion to behave the way they think it should. The rest of us, however, might want to put a little effort into learning from their mistakes. When the rubble stops bouncing and the smoke clears away, a great deal of rebuilding will be in order, and much of that will have to be done by individuals, families, and local communities, unhelped (and also unhindered) by the, ahem, intellectual intuitions of experts. A willingness to attend to the grubby world of fact, even when it conflicts with one’s preferred notions, will be a useful tool for the hard work ahead; a willingness to learn a little more about ourselves, even when that knowledge isn’t flattering, will be another.

“Believe what we tell you, not your lying eyes!” is the mantra of the management/elite class these days. Thank you for another excellent post.

I’d appreciate a recommendation for a starting point into William James, not a writer/thinker I have ever encountered before on this side of the ocean. Thanks JMG.

For those who didn’t pick up on it, our host’s “Ceci n’est pas un canard” is a reference to René Magritte’s “The Tragedy of Images”, reproduced below:

A painting of a pipe is not a pipe, just as a picture of a duck is not a duck. Magritte’s painting is another helpful warning about confusing abstractions and facts.

Greetings JMG. Happy synchronicity! I’ve been listening repeatedly to Bernardo Kastrup’s Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics… I love it…

What a relief to read. I grew up in a strictly scientific household. As an undergraduate, I had the privilege to sit in on Noam Chomsky explaining science to a room full of philosophers. It was only then I realized that science really only claims to explain and predict. A fine tool for many things, but with sharp limits and hardly deserving a government or cultural monopoly on “Truth”. Having been from the science tribe, it’s lonely not to have the fellowship of the ritual drinking of that Kool-aid.

It would be annoying to grow a garden in a domed city. You’d get no rain. Always watering… and someone or something would have to go up and push the snow off the dome so it doesn’t build up too much, unless your domes are very steep.

@JMG

Thank you for this very insightful essay. I’d like to say, though, that philosophy is one of the two disciplines being regarded with hostility, the other being history.

The reason I say this is because the myth of Progress falls apart on close examination when a thorough study of historical facts is undertaken, and it becomes hard to justify faith in Progress without resorting to the use of highly questionable logic. Of course, the hostility to these two subjects are due to other factors as well, namely, corruption, politics, economics, and finally, the sheer cussedness of human nature.

That said, I am not surprised at all to see true devotees of scientism and Progress like Neil deGrasse Tyson attack philosophy so much – after all, if people study philosophy, they might just come up with concepts and ideas that pose a threat to Progress! Similarly, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard STEM people casually dismiss history as useless, with arguments like “…maybe as a curiosity, the study of history may be fine, but now we have science, medicine and technology, so really there’s no need for history!” (they never got around to even mentioning philosophy) I’ve come to conclude, after having read your writings, that the reason history is attacked by STEM fans is because it tells us that ideas and concepts that we consider cutting-edge are very often newer, rehashed versions of ideas that were old in the Bronze Age, and that they flopped comprehensively.

There was a philosopher of Deal,

Who said: “Although pain isn’t real,

If I sit on a pin

And it punctures my skin,

I dislike what I fancy I feel.’

“Without those processes of assemblage and labeling the world would be, in James’ useful phrase, nothing but “a blooming, buzzing confusion” of unconnected sensations.”

That phrase is really a torpedo hit to “naive empirism” boat that only believes in sensations by the usual 5 senses…

Words cannot adequately express my gratitude to you, JMG, for skillfully and consistently laying down the bricks on the road we need to travel if we are to keep our wits about us and be in a position to help ourselves and others as this amazing time does what it must do.

OtterGirl

Was there ever an opportunity for a cohesive narrative or story for our global system? Like a religion, belief system, or myth that could have steered this process towards the common sense solutions you outline so frequently, where we are part of instead of on top of nature.

Maybe those stories are forming but won’t materialize in time.

“Objective evidence and certitude are doubtless very fine ideals to play with, but where on this moonlit and dream visited planet are they found?” –William James, The will to believe part VI

“The human mind can only know what it creates.”

Judging by the hundreds of pages that make up my DM binder for any given TTRPG campaign, it can’t even know what it creates very well!

Excellent post as always!

I find the Christian declaration of Truth to be a strange artifact. When I became Catholic, “Truth” is what I asked for. In the decade+ since, the main truth I get is that I can’t handle the Truth, just like Job after chapters 38-41.

Regarding the failed dream of nuclear energy:

I’m almost finished reading the book “One hundred miles from home :nuclear contamination in the communities of the Ohio River Valley” — It’s the scariest horror book I ever read and it’s non-fiction.

The amount of things swept under the rug -into the aquifers- the people harmed, workers, residents -the outright lies and collusion. It’s scary. And some of the half-life’s of the transuranic elements… we’ve only lived for a fraction of.

My great grandfather was a chemist who made something in his lab in the basement which he sent to Fernald -one of the sites covered in this book. It’s all very close to home. I’m sure there may be similar books about sites where other people live.

Thanks, btw, for showing how the failure to love wisdom has resulted in the current world views of the managerial class. & thanks for bringing up Korzybski and the “is of identity”. I think that is at play big time in relation to your post a few weeks ago about Tartaria and related phenomena of conspiracy theories.

Also I believe Tartaria was in part wiped out of the history books as part of an advertising campaign on the behest of Crest.

Hi John,

I like James, among other reasons, because he offers guidance geared to an uncertain world. For example, he tackles the issue of free will by observing that either free will exists or it doesn’t. If it does, and you’re exercising it, then you’re living up to your potential and that is much to your credit. (If free will exists, then you indeed chose to exercise it.) If free will exists and you’re not exercising it, then you’re leaving a lot of human potential on the table, and that is to your discredit. If free will doesn’t exist, then whether you behave as if it does or not, it is not to your credit or discredit, since you had no choice but to behave the way you did. So one can argue that the only course of action that has a chance of being honorable is to behave as if free will exists, and hope that it does.

Much thanks for this tour of our philosophical roots. Agreed that we neglect too much of what has been pursued by these European cum colonialist revelations. But I would like to interject one thinker who, in my estimation, has had a much more deeply seated affect on Western education and everyday living: Rene Descartes’ (1596–1650).

His lasting ideological influence on western thought was and remains profound. Not least is so-called Cartesian dualism – the treatment of mind and matter as separate realms – that has encouraged and perpetuated a mechanistic view of the world around us. Descartes’ legacy – a dualism that assumes separation between soul and body, mind and matter – has in many ways proved a poisonous one for western societies. An impoverished, mechanistic worldview treats both the planet [witness the lobbies against the realities of “Overshoot” and one of its consequences: global warming!] and our bodies [just ask a woman in the U.S. today, and an ‘essential worker’ paid minimum wage] primarily as material objects : one a plaything for greed, the other a canvas for the insecurities of what you have described in your essay; e.g., “{temptation} to treat belief in the abstractions and denial of the facts as a loyalty test for your subordinates”.

For an excellent description of the mess we’re in and a fatuous “solution”, I give you –

https://www.danablankenhorn.com/2021/12/2021-intensive-care.html

“the managerial class has reacted to its failures reacted by doubling down”

Delete second reacted, then this comment.

Your essays often bring new insight that I cannot quantify, but I sent a donation for the sense of improvement they’ve made to my life, JMG.

I had a professor, the late Edwin Allaire, who opened his early modern philosophy class with the line, “Philosophy is the history of three great mistakes: Plato, Descares, and Peano …” With that line, the attention of everyone in the class who cared at all perked up, and he dove straight into a discussion of the Six Meditations of Descartes. Long story short, my conclusion was that Descartes fouled up when he jettisoned the insight of post-classical Dark Ages and Medieval philosophy and thus forgot everything their elders knew about the limits of knowledge.

I think Kant only deserves half the credit though. David Hume argued that the raw sensations that assail us do not entitle us to claim knowledge. He also had the good graces to admit that he had no idea how we turn the disparate sensations hitting us into a tea cup. There lies half the credit. Kant reads David Hume and is blown away. Kant gets the idea that the mind itself has built-in categories that process disparate sensations into conscious experience. There is the other half of the credit. I bring this up because I think Hume too often gets forgotten. If there was a Nobel Prize for philosophy, Kant and Hume would have to share it for their work.

I also think Hume is a much more engaging writer than Kant. Reading Kant is a chore, while reading Hume is a delight. But opinions may vary on this point.

As for domed cities, I remember thinking the pictures were neat when I was a kid, but my mom telling me that no one would build them because they would get too dusty inside after awhile.

“When you see an object—say, a cup of tea—what actually happens? You experience a series of disconnected sensations of color and shape; one part of your mind assembles those into an image, and another part of your mind assigns a label to that image: “teacup.” Without those processes of assemblage and labeling the world would be, in James’ useful phrase, nothing but “a blooming, buzzing confusion” of unconnected sensations.”

This made me think of people with Autism.

The idea that our perception of truth is merely a model created by our mind, I think has a lesson for us that consistency is more important than accuracy. But still, consistency doesn’t not equal accuracy.

It is tempting to suggest that since we all share a mental model through language and culture, that the search for truth is on a little firmer ground than Kant seemed to suggest. But that’s not so; we simply share the faults of the same model. Unfortunately this seems to lend credence to some of the elements of the social justice movement that condemn whiteness and Western ways of thought. After all isn’t white Euro-centric Western culture just another flawed mental model? That being said, the social justice people don’t suggest a unified truth either. It’s as if, having ignored the logical outcome of Western philosophy, Western civilization is now under attack from those that understand objective truth is a mirage of culture and shared assumptions.

The response of conservative Americans typically falls along the lines that a shared culture and mental map and the benefits that flow from these things outweigh the faults. And for the most part I would tend to agree that the more homogeneous a society is, or at least the more it can agree on, the more it tends to peace and tranquility. But this state can’t exist forever, especially in the face of suffering. And there are many people in our society that have been suffering over the last 40-50+ years under the traditional American culture. And they have risen up. The predominant mental map didn’t work for them, so they don’t feel that they have to honor it.

I do think in some ways we are throwing out the baby with the bathwater but as long as one side wants complete revolution and the other side wants the continuation of the status quo, the tensions that brought us to this point will never be resolved, and social unrest will fester.

None of this has to do with objective accuracy, and everything to do with how society comes to agree on a shared mental map of reality that everyone can work with. It is this work that drives wars and destroys or builds societies in turn. If you are one who wants the status quo, how will you solve environmental destruction, resource depletion, socioeconomic inequality, racial disparities, and the like. If you are one who wants revolution, how will you ensure that costs of green energy transition don’t wreck the economy and get passed on to the poorest? How will you manage to help oppressed races without engendering racial animosity? How will you dismantle capitalism while still giving the common man the chance at upward mobility? How will you increase the government social programs without disincentivizing personal effort and causing budget issues and inflation?

I have never believed the canard that Americans are optimistic. I do think that we are practical and pragmatic in that we tend to think and believe that problems exist to be solved.

Off topic, if I may, the noted journalist, blogger, writer, and former diplomat Craig Murray is newly released from prison, back to blogging and not mincing words. https://www.craigmurray.org.uk/

Your bit at the end about unrealistic beliefs as loyalty tests reminded me of a thorough summary/commentary of a book I read. The book is called “Moral Mazes” by Robert Jackall, and a summary of the in-depth review by Zvi Moshowitz (a rationalist blogger) can be found here: https://thezvi.wordpress.com/2020/05/23/mazes-sequence-summary/

It’s an analysis of the dynamics of middle management in large corporations, based on interviews and research done in the 80s, but from my own experience, much of it was still true in corporations of the teens and at least some of it applies to academia of the 20s. The thing that really drew the two together, though, is that the book/summary talks about how middle managers become incentivized to do things that are *actively bad*, rather than merely negligent.

Here’s the logic: let’s say you as a manager have a choice of 3 things: 1) something that makes the company money with no ill effects on the world outside, 2) something that makes the company money and may or may not have ill effects on the outside world, or 3) something that makes the company money, but will definitely have ill effects on the outside world. If you’re being evaluated on how much money you make the company, these would have about equal incentives pushing for them. The trouble comes in when systems reward loyalty more than effectiveness (spoiler alert: any organization with more than 3 layers starts doing so at least a little bit).

Choices 1 and 2 are insufficient signals of loyalty, because you could *claim* that you picked them because they’re good for the company while secretly caring more about the outside world. Choice 3 is the only one that demonstrates for sure that you care more about the company than the outside world, and so is incentivized if loyalty is the main thing rewarded.

I share this, because it adds a troubling dimension to what you state in the post: it would be bad enough if those making decisions had to pass some reality-defying loyalty tests, but otherwise tried to do a good job. The implication here is that in very many cases, doing the job *obviously badly* in some ways becomes an ongoing loyalty test to which your promotion and identity become linked. Scary stuff.

(Separate comment to help keep replies clear)

The other thread from this post I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on is a distinction between William James and some of his predecessors I encountered on Eric S. Raymond’s blog a few years back about the difference between defining “truth” as “that which is predictive” (Charles Sanders Pierce) and “that which is useful to believe” (Pragmatism): http://esr.ibiblio.org/?p=7651

ESR is a die-hard and admirably rigorous materialist and a long-time student of Korzybski’s whose thoughts I found especially helpful when I was trying to make sense of the world from a materialist point of view. He’s also open to magical and mystical practices, he just believes they all are perfectly explainable from a material substrate.

Anyhow, from your writing and some of Jordan Peterson’s talks (especially his infamous first discussion with Sam Harris), I suspect that ESR does not place the fact/value distinction as low in the perceptive process as James, you, and Peterson might. As I said, though, I’d welcome any thoughts on this from you or any of the commentariat.

A nice breakdown of the history of modern philosophy! At one point I got a little confused: when you write “There are doubtless things analogous to space and time … as the quantum physicists showed later on, they routinely behave in ways that make hash of our notions of the way space and time work”, can I substitute something like “subatomic particles” or even “their measurements” instead of “they”?

Any lab scientist feels a small triumph just because a measurement repeats itself, no matter if the measured value corresponded to their wishes! And any neuroscientist knows the woeful abyss between our theoretical knowledge and the actual behavior of freely moving animals and people.

Since the 1980s, Judea Pearl has revolutionized the design and understanding of causal experiments by pointing out how much better normal human beings are at understanding and predicting the world than the most sophisticated statistical models were, and by trying to mimic and formalize that normal human intuition.

Sometimes I find my mind fighting to stay afloat in the turbulent abstract seas of today’s day and age and. It seems like occult philosophy and related experiences are my life raft.

I started reading Schopenhauer as my designated bathroom break book. Hopefully I can deepen my understanding of the topics you mention here.

Thanks for the great post.

“a willingness to learn a little more about ourselves”

How do we do that?

I collected a box full of quotations while in grad school. Here are two from William James writing about Hegel:

WILLIAM JAMES :: It is not necessary to drink the ocean to know that it is salt; nor need the critic dissect a whole system after proving that its premises are rotten.

WILLIAM JAMES :: The world is philosophy’s own, — a single block, of which, if she once get her teeth on any part, the whole shall inevitably become her prey and feed her all-devouring theoretic maw. Naught shall be but the necessities she creates and impossibilities; freedom shall mean freedom to obey her will; ideal and actual shall be one: she, and I as her champion, will be satisfied on no lower terms. … The insolence of sway, the [hubris] on which gods take vengeance, is in temporal and spiritual matters usually admitted to be a vice. A Bonaparte and a Phillip II are called monsters. But when an intellect is found insatiate enought to declare that all existence must bend the knee to its requirements, we do not call its owner a monster, but a philosophic prophet. May not this be all wrong. Is there any one of our functions exempted from the common lot of liability to excess. And where everthing else must be contented with its part in the universe, shall the theorizing faculty ride rough-shod over the whole?

Aligning a truthful interpretation of objective reality with the narrative of our subjective mind is the crux of living skillfully. To be in flow, to live authentically, one with Tao. Unity with reality is the close alignment of the objective and subjective. Hard to do, reducing the ego and desires, the confirmation biases, the prejudices, the mind traps, etc that are the daily minefield of life. Your insights are always welcome.

What about the notion that experience is the only reality, there being no fixed, independent or objective “Ding an sich” to which our experience refers, or which causes our experience? This still leaves plenty of room for us to misconstrue our individual or collective experience, either for lack of subjective acuity, or by secondarily superimposing all sorts of incoherent or delusional notions upon the raw data of our primary experience. Even if we’re experts: tinyurl.com/mu6r3wby

I am so very glad that flying cars are, and will likely remain, playthings of the reckless rich. In engineering terms, what makes a good car makes a poor aircraft, and vice versa. I do not want multi-ton machines made of steel and glass falling at random out of the sky when their engines fail. One of them might dent my roof!

The recurrence of doubt should come as no surprise to those familiar with Socrates, who _invented_ philosophy, and who said, “I know only that I know nothing”. He called his system of inquiry ‘philosophy’, and not ‘sophism’, which he derided; for the word ‘philosophy’ doesn’t mean wisdom, it means _love_ of wisdom. And any true lover can tell you that to love is not the same thing as to possess.

The love of wisdom is not in vain; for though the knowledge thus gained is relative and incomplete, it tends to be enough for our material and spiritual needs. I _like_ the world described by modern science; it is grand and glorious, and much more beautiful than the tiny worlds it supplanted. High technology, too, will stay with us; at least the cheaper, simpler, subtler, decentralized forms, derived from investment of thought and insight rather than money and power. Technology will advance, despite its failures; for most experiments fail. Their real value of experiments comes from what we learn from the failures.

However, not even modern technology is enough for our foolish desires, especially the desire for power over the world and others. Hubris creates its own nemesis.

Historically, what is the typical timeline for the “managerial class” to realize their errors… or get replaced? And what is the success rate of these changes, if you define success as not violating western values of human rights? The doubling down on failed policies is starting to get tiresome, but maybe a slow evolution to something new and improved is preferable if the status quo can survive and evolve long enough???

“A world of hurt”. I’ve heard that phrase many times but you’re use of it here is spot on in describing our current predicament. Thanks John!

Another thought, in looking at all the hurt caused by Covid and especially people’s response to it, when shouting dies down and we are back to more normal times, we will all have to learn to forgive. This application of forgiveness will be necessary to re-build our personal social networks and start to heal the damage. We are going to need each other.

Thanks again John

Clayton #8: Bravo! But the first line’s scansion limps. I recommend:

“There once was a thinker from Deal…”

Along the same lines, I wrote the following fable:

Sage Advice

Once upon a time a Sage placidly extolled the virtues of contemplating life with equanimity. He recommended this attitude to all, including the victims of flood, fire, earthquake, plague, robbery, rape, tyranny, atrocity and war.

He said, “If only the common folk had sufficient wisdom and character for philosophic detachment, then they too could avoid suffering!” The Sage sighed and shook his head.

Then he stubbed his toe on a rock, and he swore like a sailor.

Moral:

We all have the strength to endure the misfortunes of others.

Comment:

I stole the moral from de La Rochefoucauld. To me the Sage’s cussing redeems him. True wisdom knows when to play the fool.

Vala, you’re most welcome.

RogerCO, I recommend his book Pragmatism as a good start; like most of his best work, it’s based on a set of lectures he gave, and like everything he wrote, it’s highly readable. (That matters. If someone can’t write clearly, that tells you that they can’t think clearly…)

Jeff, it was indeed. The blog software stripped your image, but fortunately Magritte’s work is easy to find online.

Casey, good heavens. How did I not hear of Bernardo Kastrup before? I’ve just added several of his books to my get-this list; anybody who takes Schopenhauer’s metaphysics as seriously as they deserve is worth multiple close readings.

Bradley, science has its own fundamentalism, and a lot of people fall victim to it. Like most things, science is a great servant but a terrible master.

Pygmycory, two of many excellent reasons why domed cities are a really stupid idea!

Viduraawakened, that’s an important point, worth exploration. Thank you.

Robert, funny. From James’ standpoint, btw, the pin may be an illusion but the pain is real!

Chuaquin, James meant it as such. If you actually explore the process of sensory perception it becomes impossible to miss the fact that naive empiricism is an embarrassing kind of nonsense.

OtterGirl, you’re welcome and thank you.

Ynu8ipbnxu, oh, we had a cohesive narrative or story — the myth of progress. It just happened to be wrong. Modern history is the process by which that narrative played out, from its bright beginnings to its dismal end. Lacking that narrative, we’d be living in a wholly different world.

Dave, excellent! A fine Jamesian quote.

John B, I just rolled d20 and that was a good solid hit. 😉

Justin, yep. It’s a very, very ugly story. As for Tartaria — heh. Funny.

Greg, that’s one of the most elegant applications of Pascal’s Wager I know of.

Bruce, as I noted in the post, Descartes stands at the beginning of modern Western philosophy, and yes, a great deal of what we’re contending with today is a product of his ideas.

Patricia M, speaking of people with their hands over their ears going “La, la, la, I can’t hear you…”

Electricangel, thank you.

Chris, as I noted in my post, Kant was simply the last of a sequence of brilliant philosophers — Locke, Berkeley, and Hume were the others — who made his work possible. All of them are well worth reading, and I certainly wouldn’t discourage anyone from reading some good Hume.

DT, good. The wokesters grasped the fact that the standard Western worldview is limited and biased, but they failed to grasp that just standing it on its head and saying “what they say is bad is good, and what they say is good is bad” does nothing to improve the situation. They remain just as dependent on the existing worldview as before, since all they’ve done is say with Milton’s Satan, “Evil, be thou my good.” The thought that every worldview including theirs is just as limited and biased, and that we still need some kind of common ground for communication and mutual action, is outside their mental reach.

Mary, of course it depends on your definition of optimism. “Every problem has a solution” is from some perspectives a blindingly optimistic statement.

Jeff, interesting. That doesn’t surprise me at all.

Older philosophers: Mankind can know Nothing of the World

Newer scientists: Mankind can know Everything of the World

William James: A person can know Something of the World.

“Neither the whole of truth nor the whole of good is revealed to any single observer, although each observer gains a partial superiority of insight from the peculiar position in which he stands. Even prisons and sick-rooms have their special revelations”

(Talks to Teachers. 1899, p 264), as cited here: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/james/

Sorry if my simplification above does a disservice to either “older philosophers” or “newer scientists.” 😉

But I am trying to pinpoint my dismay at the whole discussion of what a person can know, and how the idea that a person cannot know the world “directly” can be seized upon as a way to alienate a person from those Somethings which they do happen to know.

And, it strikes me that this is not a million miles away from the observation made in several places, that those who cite themselves as belonging “Everywhere” (globalist outlook) actually belong “Nowhere”, and are very different in outlook from those who see themselves as belonging “Somewhere” (localist outlook).

This is because there are people, as we speak, telling me that science (not philosophy) proves in many ways (see this study, read that link) that *I* can know Nothing. Their next move, of course, is to explain that since *I* can know Nothing, I have no option but to defer to the objective knowledge that “scientific consensus” – apparently – reveals. They find it quite logical to believe that, while individual people can know Nothing, humankind as a whole – represented by “scientific consensus” can know Everything. They fail to appreciate what seems logical to me, which is that if *I* can’t know anything then no one can know anything, whether singly or in groups – even very large groups.

On the whole, I am therefore quite taken with James’ view that “each observer gains a partial superiority of insight from the peculiar position in which he stands” as it accords with the idea that it is both my right and my duty to make personal medical decisions based on my personal “partial superiority of insight” derived from being me, knowing Something, at this time, in this place.

I feel safe in predicting that I will be reading more of William James in 2022.

I thought you had mis-spelled “domed” and intended “doomed” but now I see what you did there. Living outside of Philadelphia, I can confirm it is domed. The murder rate is the highest it has ever been and the city department of health imposed a vaccine passport for the entire city. The media keeps saying restaurants only but the “guidance” (got to love that term – as if the DOH is providing wise counsel) says anywhere that even serves snacks falls under the rule. Movie theaters, bowling alleys, all sports stadiums, concert halls, and museums all off limited to non-vaccinated ages 5 and up.

Meanwhile heroin addicts shoot up in the streets, much of the city were the working class lives looks like that last photo in your post, and the city is still behind on picking up trash from the start of the pandemic. It’s a failed state by any measure, but this tiny enclave in the center, feels secure in issuing meaningly edicts all day long.

I found myself crying yesterday about it. The grief just hit me. Rather than ignore it, I let go and felt it. I could drown in it. I’m not surprised by the amount of cope people have to employ to exist under such insane conditions. I also think there are some good people who have tried to make a difference in recent years, but something cracked and I don’t think even the good people matter anymore. It feels horrible to say that. The federal, state, and large city governments are unable to manage anything anymore, aren’t they?

Will a foreign power use this as an opportunity to invade do you think? Or will it be more of a takeover within? I see the printing of another $2.5 trillion and I don’t know that there is anything to take over worth having here. Farmland?

In my opinion, our elites don’t really believe their own proclaimed ideology.

I think Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Robespierre, etc, etc, believed what they were talking about, (and are perfect cases for your analysis), but Klaus Schwab, Hillary Clinton, our politicians, media ppl, Hollywood ppl and other influencers all over the world, they don’t.

Maybe some do, but most of them not.

@pygmycory regarding comment #6…

Snow? Nah, that has an easy solution — the waste heat from using all that too-cheap-to-meter electricity produced at the nuclear power plant. Plus, a bonus: when we have to crank up the air conditioning inside the dome to deal with it, we get even more waste heat. Presto, no snow accumulation!

(I can’t claim credit for the basic idea here — Isaac Asimov covers some of this in one of the Foundation novels.)

@JMG, great timing. I just spent the last two days printing and folding William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience because it’s a 550-page doozy and I thought it would be a great book to read while experimenting with binding larger sewn paperbacks and hardbacks at home.

“Where there is mind, there is stupidity” – Eastern European proverb.

To me, it’s amazing how useful the scientific process (hypothesis -> test in the real world -> update your thinking) is.

And how most people will not ever use it.

I talked to people with kids that kept yelling at their kids and complaining because the kids never listened. Even a cat can learn the difference between an empty threat and an actual punishment. And yet people never made the connection, while their kids quickly learned what they can get away with.

I could go on, but isn’t it good news that our abstractions DON’T have to be detached from the reality?

All it takes is the willingness to discard or change them if they fail.

Anybody knows why people become so attached to their beliefs?

I think what we need is not a great reset, but a tiny one – every time you fail, just stand up and say: I got it wrong and boy am I happy I learned something!

FWIW, actual scientists don’t like Neil deGrasse Tyson any more than anyone else does. His game is power politics, not science or other scholarly pursuits, and his episodes of public jackassery are part of the routine. I’ve never met one who wants him as their spokesman, yet there he is. Tales of face to face interactions with him are enough to drop one’s jaw, including from my somewhat famous former advisor (full disclosure: I come from this background myself and hold a doctorate, though am not currently working as a scientist).

The perfect figure for you to use as a foil, in other words. He’s without substance.

It is very useful to try to weave together the big strands in western history of philosophy. The awareness of the limits of our mind’s models of our sensory observation is a good focal point. I would argue that an under appreciated distinction is between the parts of the world that are simple enough that good mental models (when informed by good scientific theories) are able to accurately predict their behavior and the parts of the world that are much more complicated. The cup of tea is pretty well understood so that the mental model can include its temperature changes over time, what forces would break it, what we would find if we dug it up after 10000 years, and pretty much any other question you could ask they pertains solely to the cup of tea. Same with planetary orbits, and much of chemistry including the quantum behavior of small numbers of charged particles like Hydrogen and Helium atoms. Quantum theory is strange to humans familiar with macroscopic things, but the observations rigorously match the expectations of good mental models. It doesn’t mean the mental models are the same as the thing itself. But the things in question are simple enough that we have refined our mental models so they are essentially never wrong on certain simple questions. It is on this success that the reputation of science should rest. But a huge number of people seem to ignore the fact that most questions of interest to humans…like how to train a child, or how to manage a team running a business, or how a species should cope with the fact that it is degrading its ecosystem…are much too complex for our mental models to adequately describe and predict.

A good example is in the pandemic. Science is able to work effectively with some fairly complex systems, so we know the genome and geometry of the variants of the virus that is killing people. The human immune though is much more complex and we can create vaccines that are effective in saving many lives but we don’t fully understand how they work or how individuals will respond. But science isn’t able to offer a lot of guidance about how to organize people to minimize transmission and or how to convince people to get vaccinated when they need it. There we end up relying on experience of what works to organize people.

I place much of the blame of the failures of what you call the “managerial class” on failures of public communication. People want to hear that science will solve their problems and that a bright future is at hand, so politicians tell them what they want to hear and scientists and managers are guided to make it happen. It slowly becomes unacceptable to point out that the promises won’t be fulfilled because the world is much more complex and constrained than people have been told. Then further levels of abstractions need to be invented to make the promises come true at least in a fashion that can be spun believably. And it has slowly descended into the direct lying we see all around us today.

I must admit that I’ve never really been very interested in philosophy. A lot of it is very abstract, and I just don’t care.

Yes, I know I can’t know everything, and the senses provide an imperfect image of the world outside myself. But I can’t get outside myself to see better what’s actually there, so after a certain point I just don’t see the point of all the fussing. I’d rather put my energy into other areas of knowledge entirely.

Especially when the teacher started talking about whether rocks were sentient and should have rights. I liked the Venn diagrams and discussions of logical fallacies, but rights for rocks?

An aphorism from E.M. Cioran’s “The Trouble with Being Born”: “It has been a long time since philosophers have read men’s souls. It is not their task, we are told. Perhaps. But we must not be surprised if they no longer matter much to us.”

JMG, it seems to me you have a near-monopoly on soul-oriented philosophy these days. Thank you for your work!

Jeff, I haven’t yet started in on Pierce, much less his modern commentators, so I’ll have to wait until I have the necessary background.

Aldarion, yes, that’s confusing, isn’t it? For “they” insert “whatever it is in the real world that we experience as space and time”. That’s intriguing to hear about Pearl. Can you recommend a source for further reading?

Youngelephant, funny. Schopenhauer’s my current bathroom reading — I’m about halfway through volume 2 of The World as Will and Representation (not for the first time, of course).

Karim, well, I’ve heard there are these fields of study called philosophy, psychology, and spirituality… 😉

JVP, thanks for these!

Tom, and yet we can’t know the objective except in a partial and biased way. As Lao Tsu put it, “the process we talk about is not the process that exists; the words we use to talk about it are not the things they describe.”

Homo Novo, the Ding an sich can’t be known, and even its existence or nonexistence cannot be known. It’s a good working hypothesis, however, to explain why when I say, “Look, the sun is rising in the east!” you don’t respond by insisting that purple wombats have just devoured the horizon.

Paradoctor, the whole history of western philosophy, neatly summarized!

Kit, it really varies, mostly depending on just how ghastly a disaster the failed managerial class causes by its delusions of competence.

Raymond, that came to mind when I was writing it, so you’re most welcome.

Scotlyn, good. The switch from “Mankind,” that grandiose abstraction, to “a person” is of course crucial. Whenever someone’s saying this or that about “Mankind” it’s usually a grab for privilege in one way or another!

Denis, the big cities are where our current process of elite failure is most evident. It’s worth grieving, but the pace of decline is such that I expect significant changes in the decade immediately ahead.

Nati, I disagree. A good con artist always starts by conning himself.

CS2, delighted to hear it! That was my first introduction to James — it was the basic textbook for the clergy training program of the Universal Gnostic Church back in the day.

NomadicBeer, most people these days identify their beliefs with their ego. It’s not “this belief is incorrect,” it’s “I am wrong” — and so they resist that with might and main. Until you recognize that you are not your beliefs, it’s an easy trap to fall into.

Loren, his denunciations of philosophy are the point at issue. Whether or not he has substance as a person or a scholar, his attitude toward philosophy is very widely shared among true believers in the civil religion of scientism.

Ganv, that’s a valid point.

Pygmycory, and that’s also a valid approach. No field of human learning is meaningful to everyone.

Fritter, now there’s a synchronicity — I picked up a volume of Cioran for the first time a few weeks ago, and it’s in my to-read pile.

I am glad to see you considering Rudolf Steiner in your essays..Steiners insights into art. education. agriculture and occult has been my inspiration for many years.His forays into the complex spiritual worlds can be a bit daunting and his christianaity can put some people off but his warnings that the materialism of the present world is leading to catastrophy is obvious by now>

@ NomadicBeer #40, JMG, and the commenariat generally

Re why folks become attached to their beliefs

I was pondering something similar after reading this week’s post. It seems to me that there is a nature course of evolution–in people, institutions, and civilizations–whereby initially-robust inquiry becomes increasingly wrapped in layers of its own creation to the point where it is completely cut off from the outside. Just a first analysis, but the cross-over point looks to me to be when the model one is using becomes more self-referential than not. If I’m building a forecast for my utility’s hourly power consumption to decide how much power to buy for tomorrow’s operations, I need to feed that model with the most recent *actual* data available. If I’m having to forecast for a string of days, then I’m forced to “cantilever” my forecast by using forecast data in place of actuals that haven’t occurred yet, but I need that actual data to get incorporated eventually, in order to keep my model “on track.” If I simply use my model output as my past inputs without ever recalibrating with actuals, my model will diverge from reality. I can give you a lovely set of numbers for power consumption on Dec 15th, 2032, but they won’t be accurate in any meaningful way.

Moreover, I wonder to what degree what we’re talking about are the ruts of well-worn grooves of in space that we encountered back in the Cos Doc discussions. Our concept of self is a set of mental habits–I’ve had mine shaken enough in these past years to realize that, although that realization doesn’t necessarily make the changes any easier. Given how much less self-awareness a society has than an individual, it makes sense that the same traps are stumbled into time and time again.

DT, the questions you posed in the final paragraph of post #20 can be answered. Note, I don’t say well answered, but suitably glib solutions are available. You typed:

If you are one who wants the status quo, how will you solve environmental destruction, resource depletion, socioeconomic inequality, racial disparities, and the like. If you are one who wants revolution, how will you ensure that costs of green energy transition don’t wreck the economy and get passed on to the poorest? How will you manage to help oppressed races without engendering racial animosity? How will you dismantle capitalism while still giving the common man the chance at upward mobility? How will you increase the government social programs without disincentivizing personal effort and causing budget issues and inflation?

1. For those who want the status quo, everyone knows his or her place and happily remains in it, not requiring more resources than that to which he or she is by custom entitled. As for upward mobility, patronage, of course. Did not the ancient Romans manage their empire through patronage networks? Away with tiresome higher education, which only makes wimps out of red blooded workers, and let the leadership pick the likely lads and lasses for elevation.

2. As for “oppressed races”, you have obviously been too much influenced by leftist agitprop. Let various communities have their own Bantustans, which will make their own contributions to the general welfare, not least as places for elite R & R.

3. For those who want revolution, international trade rules! All can prosper if we only reinvent the USA as a trading hub, an oversized Singapore. No worthy PMC need ever get their hands dirty again. Bring on the knowledge economy!

The first thing that strikes me about all those people you mentioned is how long ago they lived. The world seemed full of great thinkers a few centuries ago.

I’m not the first person to make this comment but where did all the thinkers go? Other than Santayana, is there anyone relatively recent that measures up? And in this current era we’re in, is there anyone out there at all? Or is the void staring back at us?

“ It’s one thing to manipulate abstract concepts and make a nice pretty picture out of them, and quite another to make realities in the grubby world of fact behave the way that the concepts do. ”

Ahhh, a problem artists and craftsmen have faced since caveman days. I can paint a gorgeous painting (maybe 1 in 5 tries, lol)… but ohhhhh if you could see how it looked in my head.

As an artist (university trained…. which still means something if you paint realism), most artist exercises are designed to make you stop labeing what you see, because if you look at a pipe and try to paint a pipe it’s a terrible painting, but if you forget it’s a pipe and see an interplay of color, light, and shadow, and paint THAT, the viewer will see a realistic pipe. So artists and craftsmen (and probably other people who deal directly with the raw materials of life) are a little more predisposed to recognize the world within is an imperfect model of the world out there…. But of course, human variation being what it is, not all artists will get it and not all who get it are artists.

Sincerely

Jessi Thompson

anotheramethyst

If a scientist is confusing the model with reality, you’re not really dealing with a scientist but a religious person. That whole “model is reality” isn’t just limited to scientific types though. I can’t tell you how many financial disasters start with “but our models said”.

I guess when reality is too hard to deal with, models provide comfort from simplicity. Until they don’t.

@ NomadicBeerr #40, JMG #45

Re ego-identification

One of the biggest hurdles I’ve had to overcome (am still overcoming?) is the identification of my Self with my academics and education. (I am my degrees. I am my academic experiences. I am “educated.”) There are other identifications, of course–I doubt anyone has a single set–but that’s been one of my most significant so far.

It is a jarring and humbling path, I tell you.

Hi again JMG

Re Kastrup on Schopenhauer. Kastrup’s last book is the only one specifically on Schopenhauer. Kastrup has been trying to work out his personal understanding of the world for maybe a decade or more… Only to find after writing The Idea of The World that Schopenhauer had beaten him to it by, what, well over a century…

nuclear power plant somewhere nearby turning out electricity too cheap to meter.

My favorite line of all time. I think of it with every BS promise I hear.

Hi John Michael,

You wrote: “The problem faced by this latter phase, in turn, is quite simply that the issues Kant described don’t go away just because you refuse to think about them.

I’d suggest that even a grudging or sullen acceptance is a better path than outright dismissal. Mate, the whole thing looks like a turf war, and to fail to deliver the goodies is how it will end.

Cheers

Chris

Awesome Post!

I lost a considerable interest in math as a process to Truth after it lost is veneer of “the language of nature” when Goedel sent all the puffed egos of mathematicians into a tailspin too when he demonstrated that not all mathematical truths given a framework can be known from the axioms that create that framework. What happened to me that day? I found Dogme et Rituel and here I am, meditating on the hexagram drawing.

Bravo, JMG!!

“If there’s a conflict between the abstractions you prefer and the facts you encounter, and all your training (to say nothing of your class privilege) predisposes you to believe abstractions instead of facts, it becomes very tempting to treat belief in the abstractions and denial of the facts as a loyalty test for your subordinates.”

I was subject to one of those loyalty tests recently. I’m a 30+ year veteran of the software industry, currently working for a somewhat well-known medium-sized company about to be acquired by one of the tech behemoths whose name everyone knows. In early November, at the tail end of my 7th straight glowing performance review, I was told to check out that important email from HR/Legal that went out that morning. It was an announcement that nearly everyone in the company was a federal contractor, and to be compliant with the presidential order we all had to prove that we had been “fully” vaccinated (a word whose meaning changes as fast as all the other Covid-related goalposts get moved). There were medical and religious exemptions that could be applied for, but no exemption for fully remote employees. I’ve been working from my bedroom for almost 2 years and have no intention of ever going back to the office. After thinking about it for a short time, I clicked the “I am not and have no intention…” option.

I was on the fence about getting vaccinated and did consider it earlier in the year, but rejected it because I saw it as offering more risk than benefit for a very healthy person with no risk factors and who had already had the virus, but I’m not a reflexive anti-vaxxer. My attitude towards those managing the crisis and the ways in which they were doing it were rather more toxic, for reasons too long to list here. What was amazing to me was the speed with which I went from “critical employee” to persona non grata. My immediate manager was the only person the least bit concerned, and she was “shouted at” by her manager and the one above for even trying to ask HR questions. Their reason, which I found laughable and insulting, was that it was a violation of my privacy. I quickly got the sense that mandates were precisely the policy tech companies wanted but were too cowardly to implement of their own volition, but leaped at the chance once they had presidential cover.

Possibly I was too harsh in that last assessment, because after spending about a month expecting to be terminated on the first day of January and beginning to document and transfer ownership of some of my projects, the company reversed course on Dec 9 and announced that they were suspending any enforcement of a mandate due to a district court ruling on Dec 7. But my manager and I are still awaiting future developments.

For a while I was torn between whether I was more afraid of being fired or not being fired. The prospect of leaving this industry behind and resolving some long-deferred questions about where and how I would spend the rest of my life had its charms, which for now have receded as I plan to resume work in January. But I’m proud that I failed this particular loyalty test. The idea that my employer would veto my personal medical decisions for purely non-medical reasons has offended me deeply, and not even for a law but for a doddering dotard’s executive order.

Scotlyn #35:

Once I was chatting with one of my nephews, and I said something about pterosaurs.

He gushed, “Aw, uncle, you know everything!”

I said, “Well, I don’t know everything… but I do know something.”

Suddenly furious, he said, “About what?!”

I said, “I know something about something.”

He stormed out of the room, and I called after him, “Kid, that’s the most honest answer you’ll ever get!”

John Michael Greer:

Which was my succinct summary of all of western philosophy, #30 or #33?

Too bad Mr. James was a degenerate drug abuser, he could have amounted to something:

https://www.anesthesiahistoryjournal.org/article/S2352-4529(17)30144-5/fulltext

https://kunstler.com/podcast/kunstlercast-352-another-lap-with-dr-david-e-martin-investigating-the-origins-of-the-covid-19-vaccines/

After listening to this today, I’m inclined to think that concrete wall is a lot closer than we think.

Otherwise that duck is not a duck, that pipe is not a pipe, and that “Trans” swimmer breaking all those female records is not a male and you Penn female swimmers will NOT talk to the media about it.

I know the writer Wesley Yang is worried what he calls successor ideology is going to run the technocracy for decades to come, but I’m inclined to think they are their own worst enemies and the gig is nearly up.

William Hunter Duncan

Yep, those managerial classes will design the perfect clockwork that’ll work like a dream right until you leave the clean room and get into the real worls where dust and grit jam up the delicately calibrated cogwheels.

However, lower classes are often not a passive bystander. There always seems to be the need to have absolutes, for rock solid assurances or at least very convincing lies. If one of the managerial classes dares to admit there might be a mistake, the rest of their class will pounce on them off course, but a significant number of the ones they are lording over will go to their shed to decide if it’ll be the tar and feathers or the good ol’ torch and pitchfork for this occasion.

Is that just Stockholm syndrome, some hardwired need for a chieftain or rather an unhealthy fear of uncertainty that is the cause of this dynamic? In the end it’ll always put the ones convinced of their own infallibility in charge by weeding out the doubters and they’re kept there until it eventually falls apart.

@pygmycory,

In all my fantasies of domed utopias, even after all these years of thinking about it, not one of my fantasy characters has worked out a satisfactory way to clean all that glass. (Robots? How do they stick? Suction cups? Do they follow tracks? Do they use water? How does the water get there? I guess the dome is just dirty and smoggy and/or all scratched up and sandblasted…)

Sincerely,

Jessi Thompson

anotheramethyst

Hi Community & JMG, question for you, what would you do? Option A: head for a rural secluded property in the forest learn and build a local community few tools but lots of nature. Option B: Stay in the outskirts of a failing City and live as a grifter/ recycler less nature but more bounty… Just think about it, how much stuff is left in an empty abandoned ShoppingMall or an Airport…. Your thoughts for a penny… Merry Christmas to everyone.

John, If you could comment.

“Kant, whose Critique of Pure Reason showed that the human mind can only know what it creates.”

And, “Thus we cannot know the world directly.”

Mind is a term used so many ways with different meanings dependent on the level of discussion. I think of mind on this site as mostly referring to rational thinking.

Dzogchen Buddhism has a beautiful description of Mind as clear, luminous, emptiness or space. Aware and unobstructed.

Kashmir Shaivism describes an astonished expansion that one identifies with when experienced, and, that this can be experienced, as a clear, unobstructed, spacial expansion, surprisingly visceral, and that I would describe as a circle without the dot at the center. I can not understate the descriptive accuracy of the word astonishment.

The expansion experience is probably the kensho experience Zen is so careful not to describe.

These are not rational or intuitive deductions or conclusions. They are experiences that claim to verify our identification with consciousness itself. And that consciousness and will are the creative principle of which we not only participate but actually are.

Rational, intuitive, experienced. If one knew or experienced the above directly, did we create it? Is it true? Is it the ultimate? You can’t go any farther and all your experiences of gods and devas exist within that clear, luminous, conscious, empty, space which you are …. A circle without the dot at the center.

Any thoughts John?

Yes indeed. Another very good one!

And re Mr DeGrasse Tyson et al- I always think of the summation given us by Terence McKenna. “Modern science is based on the principle: ‘Give us one free miracle and we’ll explain the rest.’ The one free miracle is the appearance of all the mass and energy in the universe and all the laws that govern it in a single instant from nothing. We are asked by science to believe that the entire universe sprang from nothingness, at a single point and for no discernible reason. This notion is the limit case for credulity. In other words, if you can believe this, you can believe anything. It is a notion that is, in fact, utterly absurd, yet terribly important. Those so-called rational assumptions flow from this initial impossible situation.”

Owen, Regarding the lack of thinkers today: There’s this blog called Ecosophia. The author, John Michael Greer, and his readers/commenters are some pretty awesome thinkers. You should probably check it out. 😉

QuicksilverMessenger–I like Sir Terry Pratchett’s summation “In the beginning, there was nothing, which exploded.” If this only appeared in a fantasy novel we could dismiss it as sheer fantasy. But what are we to make of its appearance in science books?

As for someone’s question of where the contemporary philosophers are. I think the case is the same as with contemporary literary criticism. The subject has become so inbred, arcane and removed from the concerns of ordinary educated people that it has retreated to the halls of academia, seldom to emerge. I do occasionally see a journal of philosophy (title forgotten) on the magazine racks at Barnes and Noble, which I assume tries to be accessible. But I’ve never read an issue.

Rita

Keith, Steiner is a fascinating figure, and his ability to take occult (in his terms, “spiritual-scientific”) insights and put them to practical use is among the most fascinating things about him. To my mind, he made some critical mistakes, but who doesn’t? His work deserves to be picked up and carried forward — and I’ve been reading him fairly intensively over the last couple of years with that in mind.

David BTL, fascinating. I wonder if it would be possible to work up some kind of rule of thumb to figure out when a model has become fatally self-referential.

Owen, the available philosophical space has been used up. I mean that quite literally. Every civilization has a certain amount of conceptual space available for philosophy, and when it hits the point where serious philosophizing takes off, thinkers move into that space, stake claims, and develop philosophies, until all the available options have been taken. After that you can have commentary and criticism, but there are no more great originators because there’s nothing left to discover within the worldview of that culture. We passed that point around 1900. Santayana’s a great example of how the last generation of philosophy winds down; now it’s a matter of working with the available resources, and that calls for a less colorful sort of mind.

Jessi, oh, I know. In every one of my novels there are scenes where I can still see the gap between what I was trying to accomplish and what I actually managed to write.

Owen, it’s more challenging than that. Models are all we have. We don’t have access to knowledge about reality — all we can do is model it, and hope our models have some predictive force.

Casey, good for him — it takes an unusual sort of intellectual honesty to admit that. I hope he’s also paying close attention to The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason — to my mind Schopenhauer is quite correct to say that that’s essential for understanding his major work.

DenG, it’s a good example.

Chris, I ain’t arguing!

Augusto, mathematics needs to reinvent itself as one of the arts. It’s really beautiful, like a properly composed fugue or canzone, irrespective of any claim or lack of it to truth.

Mac, thank you.

Drake, thanks for this. Yes, that was one of the examples I was thinking of.

Paradoctor, #33, but they’re both good.