By the time Richard Wagner got to work on Parsifal, his last opera, the conditions of his life had changed utterly from what they had been when he’d started work on The Nibelung’s Ring. A composer of romantic operas who’d set out to make some point in his libretto as inescapable as possible couldn’t have come up with a more drastic set of differences. He began composing The Ring as a political exile living in poverty in Switzerland, over his head in debt, married to a high-strung soprano who wasn’t especially thrilled at his antics, and who thought he was wasting time that should have gone into earning a decent living on a fantastically grandiose four-opera cycle that had next to no hope of ever being performed.

He began composing Parsifal, by contrast, as the world’s most famous opera composer and one of its most celebrated cultural figures, living in extravagant comfort in Bavaria, having all his bills covered without a quibble by that nation’s mad king, surrounded by an adoring crowd of fans and acolytes, with a wife who both adored him and knew how to manage his vagaries, and with his very own opera house in Bayreuth fully stocked with musicians, singers, and stage hands who were as passionate about his art as he was. It was the kind of stunning reversal of fortune that you can’t even dream of getting away with if you write fiction. Only real life can manage anything that absurd.

Of course Wagner was also a different person by the time he began work on Parsifal. Mind you, he was just as arrogant, self-centered, and nastily paranoid as he’d been all those years before, but he’d had a good many of his more overinflated notions about politics and the future knocked out of him by events. He’d also had the opportunity to read (and get bowled over by) Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, which gave him a constructive way to think about his own failures and, as we’ll see, an antidote to a certain number of his own worst character traits. The mere fact that Wagner was never really able to use the antidote on himself doesn’t change the fact that he did manage to recognize it, and to glimpse at least a few of his own epic failures as a human being in the mirror that Schopenhauer held up for him.

Yet the basic problem that framed The Nibelung’s Ring still remained, as pressing as ever. What was more, the conclusions to which he’d been driven in the course of composing The Twilight of the Gods brought that problem to an even sharper edge than it had ever had in those earlier days of his career, when he thought there was a simple solution to the world’s problems.

Let us grant, as Wagner did, that commodification, the process of flattening out all values so they can be expressed in terms of money, degrades everything authentically human and creates a society in which only the worst of our capacities can flourish. Let us further grant, as Wagner did after his great intellectual crisis, that revolution offers no hope of changing this, since the rebels can be counted on to sell out the moment they get within reach of significant power and wealth, and so the curse of the Ring will remain in place until society itself crumples beneath it.

Given all these things, is there any hope at all? Can anything be done to defeat, or even partly counter, the terrible burden that Wagner symbolized by Alberich’s magic ring? Since Wagner was that nearly unique phenomenon, a serious intellectual who worked out problems by composing operas, Parsifal was his way of trying to answer that question.

It’s probably worth saying in so many words that in approaching Parsifal in these terms I’m interpreting Wagner’s last opera in a way that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been explored by others. The political and economic dimensions of The Nibelung’s Ring are practically old hat at this point, not least because George Bernard Shaw discussed them at such length in the scintillating prose of The Perfect Wagnerite. I have yet to see, however, any discussion of Parsifal as the sequel to The Ring in the Wagnerian literature I have read, nor any exploration of Parsifal as a response to the same issues that Wagner wrestled with in The Ring. That surprises me, not least because Wagner stocked Parsifal with a set of signposts pointing straight to that conclusion, but there it is. It’s entirely possible that I may be as wrong as wrong can be in seeing Parsifal in these terms. Still, this is what the opera appears to me to be saying.

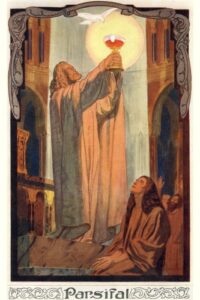

Let’s start, then, by summarizing the situation Wagner has drawn up for his version of the Grail legend. The backstory to the opera begins in a castle in the mountains, where an order of celibate knights guards the Holy Grail, the cup Christ used in the Last Supper. Amfortas, the king of the Grail kingdom, rules the knights and performs the mystic ceremony that gives the knights and the kingdom their power. The magic of the ceremony also preserves Amfortas’s father Titurel, who built the castle and founded the kingdom, in a kind of half-living condition: his voice is heard from the darkness when the knights gather for the rite, but he himself is never seen.

Yet all is far from well in the Grail kingdom. Long ago, when Titurel was king, a young man named Klingsor became a novice in the order of knights. Unable to control his sexual cravings in less drastic ways, he castrated himself, and for this act he was cast out of the Grail order. Filled with anger, he fled to the heathen lands to the south and there discovered that his self-castration gave him access to strange realms of evil magic. Thus he became a powerful sorcerer, built a castle of his own as an imitation and rival of the Grail castle, and lured the Grail knights one at a time, trapping and degrading them, to make them his servants.

When Amfortas became king, putting an end to Klingsor’s machinations was at the top of his to-do list. The new king took one of the two great treasures of the Grail kingdom, the holy spear that pierced the side of Christ, and rode south to confront Klingsor in his lair. Beneath the walls of the sorcerer’s magic castle, however, Amfortas was seduced by a woman of frightful beauty; the spear slipped from his hand; Klingsor, hiding nearby, seized the spear, stabbed Amfortas in the side with it, and vanished within the castle. The holy spear remains in Klingsor’s possession as the opera begins.

Amfortas was brought back to the Grail castle by his knights, but the wound inflicted by the spear never healed. The knights sought all through the land for some cure for the wound, but nothing they brought back gave more than temporary relief. The same was true of the remedies brought back from further afield by a strange woman named Kundry, dark-skinned and dressed in ragged garments, who lives near the Grail castle and helps the knights from time to time. What makes the wound especially problematic is that it causes Amfortas nearly unendurable agony whenever he plays his part in the ceremony of the Grail. His only source of comfort is a riddling oracle from the Grail itself that someday a pure fool, made wise by compassion, will arrive to heal him of the wound.

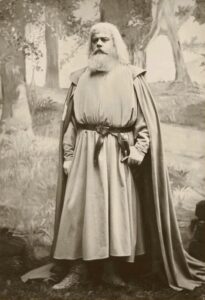

This is the backstory as the curtain rises. In those productions that haven’t done something stupid with the story, at least, the audience sees a forest glade at dawn. In the distance is the castle of the Grail and the mountains rising behind it. In the glade sleeps Gurnemanz, a veteran Grail knight, and a group of squires under his authority. As the sun rises, Gurnemanz wakes, rouses the squires, and sets them to work preparing a bath for Amfortas, in an attempt to relieve some of his pain. Kundry puts in an appearance; so does Amfortas; and then, unexpectedly, so does a stranger from outside the Grail kingdom, a foolish young man so clueless that he doesn’t even know his own name. He is the son of a widow; he was raised in the forest far away, who left home after meeting knights on the road and has wandered since then.

We can leave things there for the moment, because what has already been covered provides more than enough material to make the point I have in mind.

Notice, first of all, that the two great magical objects in this opera are identical to two of the three that play a central role in The Ring. The Holy Grail, we already know from Wagner’s essay “Die Wibelungen,” is yet another expression of the mythological motif of the Treasure Hard to Attain, the same motif that gives Alberich’s ring and the hoard of the Nibelungs their symbolic meaning. The spear is equally central to both narratives; any of my readers who have a background in the relevant traditions know already that Norse and Christian mythology share the same mythic image of a self-sacrificed god suspended in the air and pierced by a spear. Wagner and his contemporaries were well aware of this parallelism as well.

The sword alone has dropped out of the story, but then that weapon was the centerpiece of Wotan’s scheme and has no place in Parsifal. To translate that detail into the political and economic language Wagner used, revolution is not an option in play this time around; he had already seen where that leads and had no interest in tracing the same futile path again.

Notice also the remarkably close parallels between the ostensible villains of the two stories. Those parallels didn’t exist in the older Grail legends; Klingsor is absent from all but one of them, and in his one appearance, as Clinschor in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, he is a minor character in the backstory of one of the protagonist’s adventures. Wagner took that brief reference and transformed it into a character closely attuned to the equivalent figure in The Ring.

Like Alberich, to begin with, Klingsor has renounced love in order to gain power. Like Alberich, he didn’t intend this to begin with—his original motive was to serve the Grail, as Alberich’s original motive was to love the Rhinemaidens—but in both cases, their failure and frustration drove them to an irrevocable deed which gained them evil powers at a terrible price. Both the dwarf and the sorcerer are well aware of what their respective choices have cost them; Alberich’s furious dialogue with Wotan in Scene 4 of The Rhinegold and Klingsor’s furious monologue after his mockery by Kundry early in Act 2 of Parsifal express that point with equal power.

The spear is the crucial symbol here, and it’s not accidental that in Parsifal it is in the hands of the villain. Attentive listeners to The Ring will recall that Wotan at one point referred to himself as Licht-Alberich. This means “the king of the light-elves” as contrasted to Schwarz-Alberich, “king of the dark-elves;” the opposition between the lios-alfar and the svart-alfar, the light and dark elves, is a theme in the old Germanic mythology Wagner used as a resource. At the same time, of course, Wotan is also equating himself with Alberich, and for good reason. Like Alberich, Wotan was perfectly willing to renounce love in order to win power; unlike Alberich, he wasn’t honest enough to stick to the bargain he’d made, and most of the catastrophic failure of his schemes in The Ring came from that attempt to have his cake and eat it too.

The identical contrast yields one of the primary plot dynamics in Parsifal. In that opera Klingsor makes his renunciation of love in a disastrously wrong but irrevocable manner, while Amfortas sets out to do it the right way but lacks the strength of will to stick with it; that’s why he falls victim to Klingsor’s trap with its sexual bait. Like Alberich and Wotan, both of them therefore fail, and the world of the opera remains trapped in the consequences of their failure until that world is disrupted by a force from outside the pattern thse paired failures have established.

That force is not the ideal of liberty. Of all the realizations that Wagner had to grapple with in his work, that one must have cost him the most discomfort. All through The Valykrie and Siegfried, Brunnhilde represented the dream of liberty that was so important to Wagner’s own youthful ideology, the hope of the world in his time. The Twilight of the Gods marked his first challenge to that ideal of his youth, but it was a halfhearted challenge, blunted by his own sense that Brunnhilde was the real heroine of the opera cycle, and her passionate, bitter, and ultimately triumphant trajectory was therefore the theme that needed to be placed front and center at the conclusion of the entire Ring.

In Parsifal he was under no such constraint. Kundry is a character in the older Grail legends, but her role in those earlier stories has almost nothing in common with what Wagner made of her. In the tales of Chrétien de Troyes, Wolfram von Eschenbach, and their rivals, Cundrie is the ugliest and wisest woman in the world, and her role is consistently helpful: she alone knows everything that is going on, and provides guidance to the Grail seeker at the crucial moments of the story. In Wagner’s hands, by contrast, she becomes a tremendously ambivalent figure, and one with direct connections to the character list of The Ring. He equated her with Gundryggia, one of the Valkyries in ancient sources, and made the point even more inescapable by giving her the same capacity to ride at a furious pace over land and sky.

The implication is as inescapable as it is frightful. In symbolic terms, Kundry is Brunnhilde. Stripped of the glamor cast over it by the political Romanticism of Wagner’s youth, the ideal of liberty is simply one more treacherous lure in the hands of those who have renounced love for power. No help can be found there.

Instead, the force from outside that can resolve the frozen conflict between the Grail kingdom and its distorted reflection in Klingsor’s magic mirror is another parallel with The Ring. The apparently nameless and foolish youth who blunders into the Grail kingdom is almost cut from the same cloth as Siegfried—almost, but not quite. In a sense, he is Siegfried as he might have been, given a slightly different upbringing. As a result of that difference, he fails at first where Siegfried triumphed, and triumphs in the end where Siegfried failed.

The parallels are as hard to miss as the contrasts. Like Siegfried, Parsifal—for that is his name, as Kundry alone knows—was born to a widow after the death of his father and raised in the forest, ignorant of all human customs. Like Siegfried, Parsifal begins his great quest out of a simple desire for companionship. Unlike Siegfried, however, he is not raised by a greedy dwarf whose sole interest in him is as a tool to separate a dragon from his wealth; instead, he is raised by a devoted mother, and her death takes place only after he sets out on his journeys. Siegfried’s utterly loveless childhood sets him up for his betrayal of Brunnhilde; Parsifal’s wholly different childhood prepares him instead for his redemption of Kundry.

Nor is Fafner the dragon anywhere in the picture by the time Parsifal begins his adventures. The world is a different place, in several senses, by that point in the tale: we have passed from the Pagan Dark Ages to the Christian Middle Ages, but there is also a literary sense in which the world of Parsifal is what comes after the world of The Ring. If I were writing the story of Parsifal as the fifth volume in a science-fantasy series with the Ring cycle as the first four volumes—a project that I’ve considered rather more than once—I would make Parsifal the posthumous son of Siegfried by Gutrune, who fled into the forest after the catastrophe of The Twilight of the Gods, found a home in the abandoned smithy that once sheltered Mime and Siegfried, and raised her only child there, with scattered jewels left over from the dead dragon’s hoard as his first playthings. So precise a narrative chronology wasn’t necessary to Wagner’s vision, of course; the symbolic echoes he wove into Parsifal were enough by themselves to make his point.

Symbolic echoes there are in plenty. Siegfried, when he leaves his childhood home, goes to three places, one after the other. First is Fafner’s den, where he slays the dragon, converses with a forest bird, and carries away the treasure at the heart of the story. Second is the hill where Brunnhilde waits, where he braves the fire, falls helplessly in love with the Valkyrie, and embraces her and his doom. Third is the palace of the Gibichungs, where his destiny is fulfilled.

Parsifal, for his part, goes first to the Grail castle, where he shoots a swan dead, converses with the Grail knights, and witnesses but has no other contact with the treasure at the heart of the story. Next, he goes to Klingsor’s castle, where Kundry waits for him; there he braves the guardians, resists Kundry’s seductive wiles, and escapes his doom by refusing to embrace her. Third is the Grail castle again, where his destiny—a very different destiny from Siegfried’s!—is fulfilled.

The differences between these two trajectories are just as deliberate as the parallels. To make sense of them, however, we’ll have to circle back to the philosophical and political issues Wagner dealt with, and try to make sense of his answer to the great conundrum of his time and ours.

“It was the kind of stunning reversal of fortune that you can’t even dream of getting away with if you write fiction. Only real life can manage anything that absurd.”

The story of the rise to fame of the Hawk Tuah Girl and her subsequent crypto rug pull would seem to belong to the realm of the tabloids, but it happened in real life.

I have often thought that the German-speaking lands of Europe would have had a less tragic 20th Century had those regions been unified by the Austrians rather than the Prussians. The former were closer to the old Mediterranean heartland of civilization and wealth, so the region of “Danubia” (https://www.amazon.ca/Danubia-Personal-History-Habsburg-Europe/dp/0374175292) tended to be more splendorous, cultured, and elegant in my view. There is more broadly the stereotype that the Alpine Germans are the fun-loving, Oktoberfest types and the “flatlanders” in the North are the dour, disciplinary, humourless types.

Your old buddy Chris Martenson suggests that the Twighlight of the Gods is upon us:

https://peakprosperity.com/when-corruption-is-the-path/

“When it comes to an entity, company, individual or country, there’s an invisible line of corruption beyond which there’s no recovery.

Today I am going to make the case that the US government, as an entity, is too far gone to recover. Whole parts of it will have to be torn down and rebuilt from scratch.”

That is why I posted, several weeks ago, that I think we have, at best, a 2 to 4 year reprieve. I am using that to get my balance sheet cleaned up and my “ducks in a row” (to the extent of my ability to do so).

Maybe Klingsor should have followed the example of the non-celibate Zen monk Ikkyu.

JMG, what is the significance of Parsifal killing a swan? The Valkyries were swan maidens, you know. Then we have Kundry, ugly and wise becomes evil temptress? I read ahead at Wiki to see how the opera ends, and I can’t say I like what Wagner made of the ugly and wise sage.

JMG, apologies if this sounds in any way smart alec; it is a serious question. Parsifal wouldn’t be about the domestication of women, would it?

Any plain woman can tell you tales of talents unrecognized– by a high school guidance counselor who would not do her job, in my case–achievements overlooked, virtues held in contempt. All because, well, the two things, awkward Miss Plainie Janie and whatever talent God might have granted her or capabilities she might have acquired by her own work and efforts, they just don’t go together. Two things which don’t go together just don’t feel right and that means the conjunction cannot be real or true, right?

But then Parsifal obviously needed the ability to sublimate passion, without taking it as far as Klingsor did.

The two bros could learn from eachother.

I have to say, having been a fan of your blogs and books since 2008 or so, this series of posts is really extraordinary. It has illuminated and clarified so many things that I have wondered about. I understand many people and movements in different ways than I did before. I can’t wait for the next one. Also I’m sure you will enjoy this:

https://youtu.be/YnFEEnzgg_A?si=N76D6c-u6jYAQjgY

File under: Forever Jung

This book might be of interest to people here:

Carl Jung and the Evolutionary Sciences : A New Vision for Analytical Psychology by Gary Clark

“This book revaluates Carl Jung’s ideas in the context of contemporary research in the evolutionary sciences. Recent work in developmental biology, as well as experimental and psychedelic neuroscience, have provided empirical evidence that supports some of Jung’s central claims about the nature and evolution of consciousness. Beginning with a historical contextualisation of the genesis of Jung’s evolutionary thought and its roots in the work of the 19th century Naturphilosophen, the book then outlines a model of analytical psychology grounded in modern theories of brain development and life history theory. The book also explores research on evolved sex based differences and their relevance to Jung’s concept of the anima and animus. Seeking to build bridges between analytical psychology and contemporary evolutionary studies and associated fields, this book will appeal to scholars of analytical and depth psychology, as well as researchers in the evolutionary and brain sciences”–|cProvided by publisher.

Chapters: Jung and the condition of modernity : evolution, the naturphilosophen and evo devo — Fossils, anthropology and hominin brain phylogeny — Analytical psychology and the evolution of sexual dimorphism — Evolutionary theory and analytical psychology — Analytical psychology and the adaptationist paradigm : Jung and altered states of consciousness — Anthropology and analytical psychology.

The first chapter looks good… its a heavy academic text from Routledge, but may be worth wading through for someone out there.

JMG: “It’s entirely possible that I may be as wrong as wrong can be in seeing Parsifal in these terms. Still, this is what the opera appears to me to be saying.”

— Gosh forbid that any work of art could be multi-allusive, and we see patterns and meanings within one, whether consciously intended by the artist or not, that lie beneath the threshold of the obvious. Nevertheless, disclaimers for disclaimers’ sake have their reasons, not the least of which , I suppose, is keeping trolls away.

I’m well aware this is one of those things that will likely cause a gread deal of minds to breakdown, but I noticed a very interesting parallel between Klingsor and certain aspects of the radical transgender movement. The transgender movement focuses on getting people who cannot control their sexuality to castrate themselves, whether metaphorically or literally; and like Klingsor, it provides the people who fall victim to it access to a huge wealth of dark magic in the form of the ability to blame transphobes for everything wrong with their life and the ability to manipulate the massive amounts of wealth and power being directed toward “transgender rights”.

Further, if the wry observation a lot of gay people have made that trans-rights became a thing only once the gay community won their battles for equal rights and tolerance, and it has had the side effect of devestating their communities, then there is a case to be made that this is a societal effort to castrate them: and so the elites, having lost control of a community that had depended on them because of their sexuality, are engaged in an effort to castrate their own community.

(This is not to say that transgender people do not exist; however every single person I know who is obviously trans has played this game; the two people I know are trans and I think are actually trangendered both hate this game and pass easily enough that almost no one knows they are trans without being explicitly told.)

Since your last post I read all of Chretien’s Perceval. Too bad he didn’t finish it. I wish he had spent more time on Perceval and less on Sir Gawain!

The phrase “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” from the French Revolution sums up the three main values of modernity. Liberty turned into Liberalism, which stimulated the commodification of society and has metastasized into the global neoliberal industrial order that rules the world today. Of course, radicals on both sides learned that Liberalism is on a track to disaster and sought to counter it. From them was birthed Communism and Fascism, which correspond to Equality and Fraternity. We’ve seen how well those attempts went. I’m excited to see Wagner’s answer to the question of modernity. Thanks, John.

Looking forward to the next essay! I have seen on DVD the Parzifal with the unforgettably named Siegfried Jerusalem in the title role. Enjoyed it but I’ll appreciate an interpretation…

Geoff, an excellent example. One of the great burdens that writers labor under is that our fictions have to make sense; real life doesn’t have to submit to that restriction.

David, it’s quite a reasonable supposition. I imagine a weird alternate history in which, due to some bizarre chapter of accidents, Ludwig II wasn’t quietly put out of the way via drowning and went on to become the emperor of a German Empire famous for operas and architecture rather than for invading its neighbors.

Michael, well, we’ll see. People said much the same thing in the 1930s.

Justin, oh, granted. Or the Grail knights could have been less constipated about sexuality. Clearly Titurel wasn’t celibate — he fathered Amfortas — and Parsifal wasn’t celibate, either; he fathered Lohengrin the Swan Knight.

Mary, no, Parsifal isn’t about the domestication of women, though I’m sure a sufficiently dogmatic feminist critic could spin it that way. Kundry is an abstraction, not a woman — the same is true of all the characters in this most philosophical of Wagner’s operas. Kundry does make a very good frame for talking about the “virgin/whore” syndrome that used to be an important theme of Second Wave feminist literature, the tendency of men in an earlier generation to think of women as belonging to two mutually exclusive categories — the boring-but-virtuous ones you marry and the luscious ones that you cheat with — and it’s intriguing to see Wagner dealing with that, and making them a single person. If I ever get around to writing that five-volume fantasy series, I plan on doing a lot with Kundry — she’s far too interesting, complex, and rich a character to leave the way Wagner left her…

Justin, oh, Parsifal figured it out. We’ll get to that.

Nick, delighted to hear it — and thank you for that performance!

Justin, hmm! I’ll definitely want to check that out.

PBRR, no, it’s not just a disclaimer for disclaimer’s sake. As a writer, I’m wearily familiar with the way that some critics can read the most outlandish things into a text, and I sincerely hope I’m not doing this to Wagner.

Anonymoose, that’s an interesting speculation. I’ll be interested to hear what others have to say about it.

Enjoyer, stay tuned!

Robert G, he’s also an unforgettable singer. Glad to year you enjoyed it!

“David, it’s quite a reasonable supposition. I imagine a weird alternate history in which, due to some bizarre chapter of accidents, Ludwig II wasn’t quietly put out of the way via drowning and went on to become the emperor of a German Empire famous for operas and architecture rather than for invading its neighbors.”

One of the great “what-ifs” for the 20th Century is what would have happened had Kaiser Wilhelm I’s successful Frederick didn’t have such a short reign due to cancer of the mouth.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_III,_German_Emperor

Instead, “Kaiser Bill” took over with his “lovely” personality and, among other things, fired the great strategist Otto von Bismarck.

Hey JMG

Awhile ago, whilst browsing, I was surprised to discover that the famous conservative philosopher Sir Roger Scruton has also written about Wagner, a book about the Ring cycle and another about Parsifal. I am not sure if you have already heard about them but I shall leave a link to his book about Parsifal in case you or anyone else is curious.

https://www.penguin.com.au/books/wagners-parsifal-9780141991665

One contrast that struck me is that the Rhinemaidens flee seduction, but Kundry is a seductress (as are the flowermaidens, to a lesser extent).

Hi John Michael,

I’m very uncomfortable with this loose talk of the wandering fool, it seems a bit harsh and perhaps the dude is only so described because other people said so. But! The comparison to the fool provided was some bloke setting off with a mighty weapon in which to vanquish his stated foe, and yet he falls for a hot chick party on the very threshold of the enemy. That seems an extraordinarily foolish act, yet nobody seems to call the guy out on it.

For some reason unknown to me, this series of essays of your keeps bringing my mind back around to the long ago (and pivotal) encounter with the greenpiece charity mugger. Look around you, I said, none of this is sustainable. To which he replied: I feel sorry for you.

The lesser folk tread like giants where the greats fail to go.

Cheers

Chris

@D Ritz #2: Well, Brahms, from Hamburg, was one of those flatlanders — so my sympathies go with the flatlanders. However, he did wind up in Vienna for the last half of his life.

@Anonymoose #10: When I arrived in Anchorage on July 16, 1969 as an Air Force technician, two things were going on: the first moon walk was one; and then my new Air Force buddies took me out to a topless bar near the airport. Telon’s Topless. The big deal there and then was a female impersonator appearing onstage. The impersonation was quite good. I wondered if, perhaps, he/she/it were not a female impersonator impersonator. Who could tell? It was all just a sort of mind game. For some, perhaps, the notion of a male impersonating a female was titillating, but maybe he/she/it was a really a female impersonating a male impersonating a female. Nowadays, we’ve done away with the expression “female impersonator.” We call it something else now.

Are you familiar with the book The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring by Paul Schofield? I haven’t read it but I came across it while looking for a translation of the opera. It seems to be about the spiritual meaning of the opera, not the political, however.

Speaking of a translation, do you have a favorite English version? I finally settled on Oliver Huckel’s rendition of the opera as a poem rather than play:

https://gutenberg.org/ebooks/11633

I found it surprising enjoyable to read, considering I don’t usually enjoy blank verse.

David, imagine an alternate history where Wilhelm died young and his younger brother Heinrich, an extraordinary intelligent man who had one of Germany’s first aircraft pilot licenses and was given an honorary doctorate for his contributions to technology, succeeded to the imperial throne. The 20th century would have been almost unimaginably different.

J.L.Mc12, hmm! I’ll check them out.

Ambrose, good. Yes, that’s an important one.

Chris, I wonder if the charity mugger’s name was Wotan…

Slithy, no, I hadn’t! Many thanks — I’ll chase that one down soonest.

JMG, thank you for the thoughtful response. I would still like to know why did Parsival kill a swan? If every detail in these operas was put in place for a reason, why the dead swan? IDK a lot about Northern European myth and folktale, but it seems that swans were quite important.

Phutatorius;

Remember Twelfth Night? The original play would have had a man playing Viola who was pretending to be Cesario.

Same thing in As You Like It. A man would have played Rosalind who was pretending to be Ganymede.

It’s also not surprising that one of the first acts of the mustache man after the Anschluss was to visit the Hofburg Palace in Vienna to view the Spear of Longinus, which was now effectively his.

“… I imagine a weird alternate history in which, due to some bizarre chapter of accidents, Ludwig II wasn’t quietly put out of the way via drowning and went on to become the emperor of a German Empire famous for operas and architecture rather than for invading its neighbors.”

This could be the basis for a beautiful steampunk GN in which Emperor Ludwig does his castle-hopping by dirigible as well as by outrageously ornate stage coach.

I’ve always thought his drowning, and that of the doctor who accompanied him on his fatal final stroll around the lake, to be distinctly fishy. Seemingly someone must have been impatient with his extravagant habit of castle-building, rather than putting the funds into something more constructive like armaments.

A few somewhat scattered thoughts:

1. The contrast between the failures of Klingsor (succeeding at chastity in the wrong way) and Amfortas (failing in the right way) is interesting. Would a more contemporary version of the opera reverse the goal of chastity and make Amfortas the bitter husband to a frigid wife, Klingsor a jaded pickup artist (or worse), and Parsifal a naive youth who lucks into a good relationship early on (with Blanchefleur perhaps)?

2. The identification of Kundry with Brunnhilde (and thus the ideal of liberty) is particularly fascinating to me. I honestly didn’t catch that the first time through. In Huckel’s introduction he identifies her with (fallen) human nature. Her redemption coinciding with (and necessitating) her death is particularly haunting in either interpretation.

3. On of the curious features of the Western mind is the belief in some political panacea: with this One Weird Trick, all your problems will go away! The sheer cussedness of things keeps hitting us over the head but for some reason we keep at it.

If Wagner considers Kundry to be his old lady Liberty from his youth, shorn of her glamour, and now merely a sexually bewitching figure, then the virtue of chastity or at least sexual restraint is what permits Parsifal to defeat the drag queen liber all and restore the Grail Castle. In my youth, I was all in for sexual freedom and gay rights. Now on the other side, I see that many old friends are dead from a sexually transmitted disease. Back in the day I mused to myself how I was more celibate than a monk thanks to the fear of HIV. Sexual liberty is just one type of liberty though, and I look forward to JMG’s next installment with great anticipation.

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Trubujah/David’s nephew Jace, who is in hospital with a fever at a time when is immune system is compromised due to chemotherapy, heal quickly from this fever, and may he and his mother and family be lent strength spiritually, mentally, and physically through this process.

May 1 Wanderer’s partner Cathy, who has bravely fought against cancer to the stage of remission, now be relieved of the unpleasant and painful side-effects from the follow-up hormonal treatment, together with the stress that this imposes on both parties, and may she quickly be able to resume a normal life.

May Ron M’s friend Paul fully recover from the debilitating illness that has rendered him bedridden as well as recover from the spiritual malaise/attack that he believes is manifesting the illness.

May Jennifer’s newborn daughter Eleanor be blessed with optimal growth and development; may her tongue tie revision surgery on Wednesday March 12th have been smooth and successful, and be followed by a full recovery.

May Mike Greco, who had a court date on the 14th of March, enjoy a prompt, just, and equitable settlement of the case.

May Cliff’s friend Jessica be blessed and soothed; may she discover the path out of her postpartum depression, and be supported in any of her efforts to progress along it; may the love between her and her child grow ever more profound, and may each day take her closer to an outlook of glad participation in the world, that she may deeply enjoy parenthood.

May Other Dave’s father Michael Orwig, who passed away on 2/24, make his transition to his soul’s next destination with comfort and grace; may his wife Allyn and the rest of his family be blessed and supported in this difficult time.

May Viktoria have a safe and healthy pregnancy, and may the baby be born safe, healthy and blessed. May Marko have the strength, wisdom and balance to face the challenges set before him. (picture, update)

May Peter Evans in California, whose colon cancer has been responding well to treatment, be completely healed with ease, and make a rapid and total recovery.

May Debra Roberts, who has just been diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer, be blessed and healed to the extent that providence allows. Healing work is also welcome.

May Jack H’s father John, whose aortic dissection is considered inoperable and likely fatal by his current doctors, be healed, and make a physical recovery to the full extent that providence allows, and be able to enjoy more time together with his loved ones.

May Goats and Roses’ son A, who had a serious concussion weeks ago and is still suffering from the effects, regain normal healthy brain function, and rebuild his physical strength back to normal, and regain his zest for life. And may Goats and Roses be granted strength and effectiveness in finding solutions to the medical and caregiving matters that need to be addressed, and the grief and strain of the situation.

May Kevin’s sister Cynthia be cured of the hallucinations and delusions that have afflicted her, and freed from emotional distress. May she be safely healed of the physical condition that has provoked her emotions; and may she be healed of the spiritual condition that brings her to be so unsettled by it. May she come to feel calm and secure in her physical body, regardless of its level of health.

May Linda from the Quest Bookshop of the Theosophical Society, who has developed a turbo cancer, be blessed and have a speedy and full recovery from cancer.

May Frank R. Hartman, who lost his house in the Altadena fire, and all who have been affected by the larger conflagration be blessed and healed.

May Corey Benton, who is currently in hospital and whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer. Healing work is also welcome. [Note: Healing Hands should be fine, but if offering energy work which could potentially conflict with another, please first leave a note in comments or write to randomactsofkarmasc to double check that it’s safe]

May Open Space’s friend’s mother

Judith be blessed and healed for a complete recovery from cancer.

May Peter Van Erp’s friend Kate Bowden’s husband Russ Hobson and his family be enveloped with love as he follows his path forward with the glioblastoma (brain cancer) which has afflicted him.

May Scotlyn’s friend Fiona, who has been in hospital since early October with what is a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, be blessed and healed, and encouraged in ways that help her to maintain a positive mental and spiritual outlook.

May Jennifer and Josiah and their daughters Joanna and Eleanor be protected from all harmful and malicious influences, and may any connection to malign entities or hostile thought forms or projections be broken and their influence banished.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

I must admit I always took Nietzsches approach to Parsifal, good in theory but in practice a sort of resignation, someone who gave up the fight because they took it all too seriously in the first place as an unbridled idealist. Wagner circled right around and found (Christian) religion, as they all tend to do.

I’m interested to hear your take.

Hi John Michael,

Oh my! Perhaps it could be suggested that they were in essence Wotan, what with all that entails as to the narrative outcome. Far out, they are in some serious trouble nowadays, and few organisations could field such a verdict. You know what though, all those protesters probably used the very products they were protesting about – and that’s a problem. It’s a story which makes absolutely no sense to me.

Man, I looked into that Wotan abiding abyss, and simply walked away and did something else with my life. The charity mugger merely confirmed my worst fears as to the underlying spell, for that is what it is.

Presumably the Grail and Spear are also subject to entropy, and so the Knights and King can never cease their vigilance? Dunno.

Cheers

Chris

You get the sense a lot of these “conundrums” are people who aren’t happy with tradeoffs and want to hold their cake after having eaten it. To me, interesting choices are precious in this realm, there are so few. And one of the things that make a choice interesting is the inevitable tradeoff, where you have to give up something to get something else.

I want it all is equivalent to I want nothing.

One of the things I still marvel at is how far you can get wanting two contradictory things, if you are singleminded and fanatical about it. It’s amazing to watch – from a distance. Not so much up close though.

Mary, the swan’s complex, and we’ll be discussing it in the next installment.

David, since Hitler was a crazed Wagner fan, not surprising at all!

Kevin, since I first read about his death I’ve assumed he was murdered. Yeah, the rise of Ludwig the Great, first emperor of the Artistisch-Operatisch Deutsches Reich, would make for fine steampunk.

Slithy, thank you for this. I’m far from sure that chastity has lost its value today, unfashionable though it is — keep in mind that faithfulness in marriage is also a form of chastity — but you’re right that the renunciation of love can take place in many ways. As for Kundry, to my mind her death is practically an afterthought, and could easily be dispensed with — it’s not like the deaths of Brunnhilde or Isolde, which are essential to their respective stories. If I do that fantasy series the equivalent character will do something more interesting.

Michael, understood. The thing that nobody involved in the sexual revolution seems to have grasped is that “Just Do It” is as mindless and unsatisfying as “Just Say No.” As usual, the opposite of one bad idea is another bad idea…

Quin, thanks for this as always.

PumpkinScone, I see you (like Nietzsche) fell for Wagner’s trick! Parsifal is anything but Christian — but we’ll get to that in due time.

Chris, yep — somebody or other hit their spear with a reforged sword, and the spear is in the process of being shattered. It’s a familiar story.

Other Owen, excellent! Manly P. Hall wrote somewhere that the gods set a table full of every imaginable kind of goodies in front of humanity, and said, “Take whatever you want…and pay for it.” It’s the endless attempts to take goodies without paying for them that renders human life so entertaining to the gods, and so often miserable for us.

Total aside, but one that for me is very exciting and you may be the man to understand it. In “The Farfarers” a Book by Farley Mowatt of “Never Cry Wolf” fame, about how incredibly obvious and certain and easy it was that the North always could almost canoe from the Norway>Faroes/Oarkney>Iceland>Greenland>Vinland, and he follows them extensively though time through the whole book. A must read, really. What are their names, the names of this mysterious people? The Albs. You see them everywhere, but nobody knows who they were because they receded BEFORE the Celts who were driven by the Romans. But you see their remnants everywhere. ALBania. through Europe, all the way to ALBion, the name for England.

And what you just added makes this more. “Licht- ALB erich. This means “the king of the light-elves”

Now that may be just your basic German, but in the context of Mowatt wondering at this but not being able to solve, not having a clue, that may be relevant for someone.

Who are are these Mysterious ALB / ELVE people who have their own nations and own ways? That live somewhere but can never be found? And recede to the WEST, as The Holy Grail, Arthur and ALB/ AVA Lon?

Since the foundational history of Germany was mentioned here, I would like to add that I think a Germany, united by Bavaria or Austria-Hungary might have had, among other things, a less obtuse foreign policy, but I don’t see this as guaranteed due to the geopolitical environment and the fact that Germany didn’t and doesn’t have easily defensible borders for founding an empire.

About Parsifal and Klingsor, it occurred to me that sexuality as a theme seems to play an important role in the way that the problem of how to overcome the commodification of the modern world is conceptualized. Might Wagner have had the idea that the solution to the problem he treats in Parsifal is the rejection of “bread and circuses”, the way the Roman Empire and the modern West alike bind their constituency to its political and ideological influences?

Happy Equinox, whether spring or autumnal, to all wherever you are.

“his voice is heard from the darkness when the knights gather for the rite, but he himself is never seen”

It was probably entirely off base for me to think that this sounds suspiciously like God (perhaps, “the Father”; perhaps, “a god”).

I’m really looking forward to where this is going. I’ve long been skeptical of Liberty and Revolution; at the same time, I can see why they appeal to so many. So if someone else recognises them as traps and looks for another way, I’m automatically interested.

—

@David Ritz #2 I don’t know… Don’t forget where Hitler himself came from, and where his movement kicked off. Even the word “Nazi” was apparently originally a slur for South German bumpkin (from a diminutive form of the stereotypical “Danubian” name Ignaz, not from National Socialist). Conversely, some of the German officers who plotted against him were from the disciplined north (von Kluge from Posen, for example, who apparently took great offense to Hitler dragging the German army’s military honour through the mud).

I do quite like the Ludwigreich, though (Ludwigsreich?). It reminds me of Nikolai Gumilyov’s giddy WWI-era notion of likeminded poets taking over national governments to bring about peace, which he shared with a baffled G. K. Chesterton while visiting Britain as a break from fighting as a volunteer for the French on the Western Front. He couldn’t think of any fellow-poet to entrust with Germany, though, and his pick for Italy – Gabriele D’Annunzio – was probably inexpedient from a pro-peace standpoint.

The part about Klingsor reminds me of the ‘protestant work ethic’ and how Christian ethics are often about amputating the parts of ourselves that are deemed to be sinful. The protestant work ethic was at first about frugality and discipline, but has metamorphosed over time into the unrestrained greed and self-interest of modern industrial capitalism.

“He began composing Parsifal, by contrast, as the world’s most famous opera composer and one of its most celebrated cultural figures, living in extravagant comfort in Bavaria, having all his bills covered without a quibble by that nation’s mad king, surrounded by an adoring crowd of fans and acolytes…” LOL this gives me hope for my original music. Clearly it’s not over until the fat mezzo sings.

Interesting, JMG: in your description of Parsifal so far, it almost seems as if it is a reprise of The Ring, now that Wagner’s vision has changed (or his illusions have dissolved, thanks in large part to Schopenhauer’s work). I look forward to seeing how (if I understand you correctly so far) the opera Parsifal will reveal the way back to the de-commodification of nature – something that neither the classical nor romantic views are able to accomplish. My suspicion is that the path that needs to be tread is the dissolution of civilization itself: bringing the people both ‘down to earth’ and in touch with the metaphysical again. A rebirth of sorts, but not of civilization per se. Perhaps more a ‘reset’.

Speaking of the dissolution of civilization, just today I came across a brilliantly written piece by none other than Pepe Escobar, who writes about the current unravelling of the West and invokes both Spengler and the lyrics of Bob Dylan’s “Hard Rain”. Even more interesting is a link that Pepe has provided to an article on Spengler and Alexander Dugin, written by Constantin von Hoffmeister. Some very familiar lines of reasoning in there that remind me of your writings over the years, JMG. Well worth a read, in my opinion!

Pepe’s article here: https://www.unz.com/pescobar/a-hard-rains-a-gonna-fall-from-the-west-down-to-the-east/

Von Hoffmeister’s substack article here: https://www.eurosiberia.net/p/dugin-and-the-decline-of-the-west

… and for the cherry on top (which, in a strange way, ties together the artists and writers mentioned above), today I just encountered the first new folk-styled anti-war song that I have heard in I can’t remember how long! Kinda reminds me of the anti-war songs I heard on the radio when I was a wee boy! But the lyrics are verrrrrry current and rather ominous. “War Isn’t Murder”, written and performed by a relative ‘unknown’ by the name of Jesse Welles. What a breath of fresh air! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8E9l_i6HPYM

There’s a lot to unwrap here and I think JMG is on to something. As proof of his intuition, France has just asked for the return of the Statue of Liberty.

Daniil Adamov: “It reminds me of Nikolai Gumilyov’s giddy WWI-era notion of likeminded poets taking over national governments to bring about peace…”

Or the network of airmen from H.G. Wells’ “The Shape of Things to Come” that rebuilds civilization and enforces world peace as the Air Dictatorship (movie version: Wings over the World).

Hello Archdruid and community!

Is it just me, or does it look like the young and hot-blooded Wagner grew progressively more religious as a Christian with age and experience of the world? Walhall is replaced by Monsalvat, the hall of braves by the mountain of salvation. The king of the gods is now the king of a Christian Kingdom, the hero demigod is now a Ser. Also, is it just me again or is Kundry is a little Loge-ish?

Also, I have thus far lived under the impression that Dark Elves are a purely modern fantasy element. I didn’t know that Svart-Alfer has a basis in mythology. I had always assumed that “Dark Elf” is a poor attempt to try and make a cool and noir-sounding fantasy race. In that vein, I recall that Tolkien devised the Orcs and Goblins to be corrupted cousins of the Elves. That does sound like his interpretation of the Dark Elf.

@Justin and non-celibate Zen monk Ikkyu.

Oh dear, you are probably right. I have always admired the honesty of Ikkyu even in those matters.

Just a thought re the potential transgender theme which Parsifal might be foreshadowing…

It has struck me that what talking of “gender” instead of of “sex” is attempting to drown in a bathtub of fluidity, is sexuality… One can imagine a machine playing with gender as “flavours of expression and appearance”, more easily than one can imagine machines feeling the pull and attraction and interaction that comes with sex.

Which is to say I wonder if, with making gender “fluid” and whatever you’re having yourself, we are just trying to drown the human, and natural, rhythms, interactions, and interrelatedness, that sex provokes, albeit differently than (say) the Church fathers did.

Rajarshi @41, nope, those fantasy authors are culturally appropriating 😀 . The svartalfar are discussed in the Prose Edda; one of the Nine Worlds is Svartálfheim, their dwelling-place (Alfheim being the home of the Ljosalfar or light elves). Among Heathens I believe the majority opinion is that svartalf is another name for a duergr or dwarf, but some think dwarves and dark elves are separate species, the latter more resembling the dangerous Folk of Celtic lore.

Kimberly Steele @ 37, I am not in general a fan of RW’s music, but he did give Kundry some powerful arias. This is not quite the fat mezzo, rather the queenly falcon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4z5NGyT2inU

As was Callas, one of a kind. We’ll not hear her like again.

Ecosophy Enjoyer, I grew up, in an atheistic household, a tale for another time, amid the remnants of WASP culture. American Protestant society based itself on the virtues of, as you say, industriousness, thrift, frugality, self-reliance and belief in the need for and efficacy of both faith and reason. In public policy, this meant good government, rule of law and public education.

All of this did not morph over time, it was deliberately sabotaged by advertising, rightly and accurately described by our host as a form of sorcery, and mass market consumerism. The notion that private thrift is a public virtue has gone completely out the window because someone might lose money from the right and our clients need those jobs doing things adults used to do for themselves from the left.

Michael S. Today’s news is that the King of England is going to offer the president, not us citizens, we get nothing to say about it, some sort of associate membership, or so it will be described, in the British Commonwealth. It lacked only this. Meghan gets to be some sort of Jr. Queen. Hey, she’s gorgeous, and us American women who actually, you know, get our hands dirty working, cleaning our houses, gardening, and so on are just jealous hags. And the pres. says the Commonwealth is “beautiful” what other recommendations are needed, right?

Just as I always knew, the MAGA faction and the Christian Nationalists are covert monarchists at heart. Because it needs a strong monarchy to keep the hoi polloi, all of us unprepossessing nobodies, in line and spending.

>As proof of his intuition, France has just asked for the return of the Statue of Liberty.

Now that has to be the most amusing thing I’ve heard today. You know that Trump is essentially a car dealer. I can just see it now – sure, we’ll be happy to put you back in that statue, here’s an easy payment plan, just sign here. And oh, we’ll need to run your credit. What’s that? Your credit came back negative? Oh my, we’re going to need more upfront from you then. Do you have a trade in perhaps? Well, maybe you can put some earnest money on it while you figure out what you want to do? Come back and see us!

This is *totally* unrelated to this week’s post!

But I’ll forget if I don’t mention it.

Bill and I are doing a DIY writers’ retreat in Ocean City, MD. The off-season is cheap and the place is deserted.

Today’s Wall Street Journal (I saw it at the library, yes, OC has a public library) featured London druids as the above the fold front page picture! I can’t remember the caption but I thought you’d be amused.

One so rarely says “The Wall Street Journal” and druids in the same sentence.

Hi John Michael,

I’d never quite thought of the reforged sword that way before. Interesting. I’d presumed it was a one off thing and with the sword eventually being repurposed into a lesser sword or a more useful pitchfork. So, is it a cycle of renewal, kind of like that inverted bell shaped curve represented in the Hubbert curve, but with what happens on the underside of that chart line?

Cheers

Chris

Siliconguy #22: “Remember Twelfth Night? The original play would have had a man playing Viola who was pretending to be Cesario. Same thing in As You Like It. A man would have played Rosalind who was pretending to be Ganymede.”

The mixup of the sexes is a recurring theme in Shakespeare – I think he was making a point about how every woman has some masculine traits, and every man has some feminine traits. Jung expanded on this idea with his discussions about the “anima” (inner feminine) and the “animus” (inner masculine). Of course, that’s a very old idea that shows up in art and mythology worldwide, as Jung describes in “Man and His Symbols.”

@Yavanna #50 & @Silicon #22: another fun thing about sex-switching in Shakespeare’s plays (and any other plays written in Elizabethan England) is that at the time all the female roles were played by boys or very young men. And the audience knew it. So it was entertaining to watch a male playing a female – and if the female role was impersonating a male that made it a double ‘gender-bender’: double the fun!

Some questions I have reading this, after visiting a castle some miles away from my own.

Is there a war between people who seek to serve humanity with humility, and people who seek to pretend to serve?

Who pretends to serve and why have they rendered themsleves useless? Why have they travelled to a realm of delusion and evil magic? How do they mirror the lives of those who truly serve? What have they stolen?

What has been witnessed by ‘those who seek to truly serve’ ? What has happened to their virtue?

Who will emerge from the mists of the forest groves, from the wild underworld, from nowhere? How will they wend their way through these realms? Who will they serve and what will be there purpose?

We are waiting for you.

First things first–

JMG, if you can work it into your schedule, PLEASE write the Wagner operas into a book–Wagner is not that accessible, and the message about commodification is a very important one!

#10.

Anonymoose_canadian says:

“…The transgender movement focuses on getting people who cannot control their sexuality to castrate themselves, whether metaphorically or literally; and like Klingsor, it provides the people who fall victim to it access to a huge wealth of dark magic in the form of the ability to blame transphobes for everything wrong with their life and the ability to manipulate the massive amounts of wealth and power being directed toward “transgender rights”.

“… there is a case to be made that this is a societal effort to castrate them: and so the elites, having lost control of a community that had depended on them because of their sexuality, are engaged in an effort to castrate their own community.

Holy Toledo, Anonymoose! That’s an amazing insight! It reminds me of some of the things that Violet Cabra used to say– She too sometimes said that she was convinced to go the transgender route, and only too late found out that she really was a gay man. Most transgender “treatments” result in sterility, whether caused by drugs or surgery. When conducted before or during puberty, the damage is lasting or irreversible.

#11.

Ecosophy Enjoyer says:

…The phrase “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” from the French Revolution sums up the three main values of modernity.

Liberty turned into Liberalism, which stimulated the commodification of society and has metastasized into the global neoliberal industrial order that rules the world today. Of course, radicals on both sides learned that Liberalism is on a track to disaster and sought to counter it. From them was birthed Communism and Fascism, which correspond to Equality and Fraternity. We’ve seen how well those attempts went. …”

Holy Cow again! Yes, the French Revolution really was not that helpful. France continues to be a wellspring of harmful philosophies. I had not thought of ‘Liberalism, Communism and Fascism’ as the Jungian Shadow side of ‘Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite,’ but there it is…

Thanks John, for covering this, and thanks to all for their comments

Merely to say thanks again JMG for this fascinating series on Wagner, which has opened my eyes and ears to many things I had sidelined. Not least of which is Parsifal, which I tended to disregard thanks to Nietzsche. Some extraordinary music! A great many things to ponder.

For what it’s worth I think the grail is consciousness absolute. And no I haven’t discovered it though, for what it’s worth I’ve been to two places with which it is often associated – Glastonbury and Montserrat – both magical places. Of all people Heinrich Himmler went to the latter hoping to find it!!

I remain a devoted fan of Italian opera but my horizons have been seriously widened!

@Ron M

“at the time all the female roles were played by boys or very young men. And the audience knew it. So it was entertaining to watch a male playing a female – and if the female role was impersonating a male that made it a double ‘gender-bender’: double the fun!”

One of my professors at university said there were cases of women pretending to be young men so they could join the theatrical troupe. So they were females pretending to be male actors pretending to be females characters pretending to be males. If this was a well-known occurrence, imagine the fun of trying to figure out what was what when you could never be too sure of the actual sex of that person on stage.

Well, I’m probably way off here, but our recent elections have been on my mind, and when I read that part about Amfortas riding out to defeat Klingsor, only to forget about all his noble promises at the sight of Kundry, I was immediately reminded of our own Friedrich Merz who rode out to slay the excesses of our past left-left government, only to turn around and forget all about them in the tight and ever tighter embrace of the SPD. 75% of people in a recent poll now say he’s betrayed the electorate (as per Die Welt: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article255753940/Umfrage-Drei-Viertel-der-Befragten-werfen-Merz-und-Union-Waehlertaeuschung-vor.html), and there has been some shedding of members of the CDU… but it’s all useless, because now they have four more years to run this country into the ground.

Waiting for Parsifal to show up already. A lot of people now hope that the AfD will get the majority of vote in 2029. But it seems more likely they’ll whip us into a war with Russia. The papers are full of articles calculating how many dead we’ll have per day, and how to “prepare” the hospitals for that… It’s total, freewheeling madness over here. You once wrote that you’re skeptical that a planet’s ingress into a sign signifies anything, but this feels like Neptune in Aries – mass delusion centering on the prospect of war.

Dear JMG

I am beginning to worry – a wee bit, anyway – that you may be *talking* too much about this 5 part fantasy ring cycle, and diluting the energy for writing it.

Please, leave us drooling a bit, if needs must, but say no more!

@Michael Gray #42/Justin Patrick Moore #4

When Buddhist monks from many nations gather together, nobody knows where to seat the Japanese delegation. If they are sat with the laypeople, where they actually belong as householders, in their elaborate robes, it is humiliating and insulting to them. They cannot be sat with the monastic sangha because they do not possess the monastic vinaya, as their own lineage has been corrupted. So they are usually awkwardly placed in a separate area by themselves. This shameful situation is the legacy of Ikkyu and others like him.

@Tengu: reminds me of the kids I sat with at lunch in highschool.

I agree Parsifal isn’t merely recapitulating standard Christian narratives of redemption through the Church, Jesus, grace, etc. when all else has failed. But I do see many elements of it as criticism (sectarian or otherwise) of various points of Christian dogma and practice. Klingsor’s self-castration evokes the Roman Church’s celibate priesthood. The Grail Ceremony being merely palliative rather than transformational evokes the character of grudging public Christian ritual: limited temporary absolution offered at frequent intervals. Amfortas’s wound might seem to represent original sin, but it could also (more plausibly IMHO) represent acquiescence to a self-defeating doctrine of original sin. Likewise the pain Parsifal feels (but ultimately avoids) from Kundry’s attempted seduction isn’t the burden of sin but the undeserved guilt that’s Klingsor’s stock in trade.

Hmm. I’ve now been sitting on this comment for two days. I’m going to go ahead and post it, but it feels more like a glancing blow off of the opera’s meaning rather than a direct hit.

JMG–on literature and reality. Jane Austen’s niece sent her a story for criticism in which a character broke an arm and still rode several miles to accomplish some task. Jane criticized this as unlikely, and the niece complained that it had actually happened to a relative of theirs. So, Jane explained that while you had to accept that an unlikely thing had occurred in life, readers still might reject it in fiction. Similarly, Jane never wrote a scene in which only males were present and conversing because she was aware that men acted and spoke differently in the absence of women than in their presence. Obviously not all authors accept this limitation.

Myriam–there used to be a well-known drag club in San Francisco, Finnochios’. The performances were excellent. We used to joke that it would be fun to take the brother-in-law from out of town; tell him (falsely) that there was one “real girl” in the show and have him try to guess which one. I can’t recall the title but there is a film about a male actress in the time of Charles II, when women are being allowed on the stage. This actress has spent his entire career portraying women and has no idea how to transition to male parts. An interesting film.

On gays and the transgender movement–many adult lesbians regard the transitioning of young women as a way to prevent tomboys from becoming lesbians. While on the other hand male to female trans want to claim to be lesbians and complain that rejecting them for having a penis is transphobia. One must also consider that Iran considers transgender surgery a “cure” for male homosexuals. It seems odd that the generation of feminists who tried to overcome gender stereotypes have been followed by a generation that are reifing gender in a weird sort of way.

Rita

Is this man a modern day Parsifal?

Reviving Rivers with Dr Rajendra Singh – The Waterman of India

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_N9PIBATSFw

Here in South Australia, we are close to tipping over into a point where we won’t even have any rain events to make this happen. Like the Atacama desert, like Arakis…

Check out the ABC (Aus gov) website for info on our drought.

And what do we do? Chop down backyard trees and gardens, bulldoze the house and put up 3 in its place, with a big dark grey metal roof. the perfect heat sink!

We are creating our own doom.

I could list so many more examples, but its just too depressing.

When I walk in the evening, I see the suburbs getting shabbier and shabbier.

But our pollies are clueless. And paid off by the big pay no tax billionaires, such as the Gas Giants in QLD who exported $36 billion and once again, paid zero tax.

I f anyone is interested in seeing how we continue to shoot ourselves in the foot, search the Macro Business website, a lot is paywalled, but there are still many free articles, charts and graphs.

To Chris, I just read your last post, may you get that rain you need, my tanks though much fewer are pretty much the same.

Regards, Helen in Oz (Dune)

Perhaps you will offer this series as a self published book on amazon?

Good stuff.

There’s a guy I follow on LinkedIn who I knew professionally while living in Japan, Glen Wood. Glen was heavily penalized for taking parental leave to take care of his prematurely born child, and his years-long (the justice system is pathetically slow in Japan) case became fairly well known by the foreign press in Japan, and he posed a question today and I have a very different perspective on it now that I have read this series of posts.

“What if workplaces celebrated parenting instead of punishing it?

Imagine a world where taking parental leave wasn’t a career death sentence…

We don’t need to choose between family and work—we can have both.”

I’m pretty sure that, up until the end of The Ring Cycle at least, Wagner says you can’t have both, and the illusion that you can have both is one of the things that drives revolutionaries to keep rebelling against a system that, if they do succeed, they end up perpetuating anyways.

So, I’m really looking forward to the conclusion that Wagner arrives at with Parsifal. Is it really as simple as returning the ring to the Rhinemaidens?

Scotlyn, he’s just getting warmed up! It’s a motherlode. And since it’s cultural history, not sure same rules apply. The liberty, legality and fraternity observation and pairing w liberalism, communism and fascism is…high level Jedi stuff I have to say.

Dzanni, I read The Farfarers in 1984 and thought it was very plausible. Note that that syllable alb- is also behind the name of the Alps; it was a widely held theory a century ago, and still seems reasonable to me, that the elves of legend are folk memories of surviving populations of pre-Indo-European peoples in ancient through medieval times.

Booklover, we’ll get to that!

Daniil, it’s quite a plausible interpretation, especially when you remember that Wagner and Nietzsche were good friends for a while.

Enjoyer, excellent. Yes, that’s an important parallel.

Kimberly, the entire history of music is dotted by stories of composers who used to be poor and unknown and then finally got the attention they deserved. Here’s hoping!

Ron, stay tuned. It’s nothing so simple.

Michael, yes, I heard of that.

Rajarshi, no, he used Christian symbolism but he was never a Christian. We’ll get to that. As for dark-elves, nope — they’re in Old Norse sources.

Scotlyn, that’s a fascinating suggestion and I think you may be quite correct.

Teresa, fascinating. The Freemasons sometimes have statewide meetings at Ocean City in the off season — Sara and I spent some pleasant long weekends there.

Chris, it could be, though Wagner never really developed that.

Ian, any attempt to categorize all of humanity into two and only two classes is misguided from the start. We all contain both those traits.

Emmanuel, as I’ve said repeatedly, it’s being turned into a manuscript as I write it. The question is purely whether I can find a publisher.

Belacqua, you’re welcome and thank you. Once at Glastonbury I happened to be shown one of the several vessels that have been claimed to be the Holy Grail. I asked the young woman who carried it, “Whom does the Grail serve?” She looked thoughtful for a moment, then said, “I think each of us have to learn that for ourselves.”

Athaia, it’s a classic example of the return of the repressed. Germans have tried so hard since 1945 to be “nice Germans” that it was inevitable that they’d find some excuse sooner or later to go to war with the world again. I suggest you get out while you can.

Scotlyn, I was planning on that. I’ve succeeded in solving a few of the core plotting problems, so it’s moved up the stack.

Walt, good. Yes, Parsifal contains quite a bit of critical commentary on Christianity as it existed in Wagner’s time.

Rita, to my mind those show just how good a writer Austen was.

Helen, I suggest you start building a sietch and getting a head start on learning the skills needed by a sayyadina…

Bliss, not on Amazon — I won’t have anything to do with them, since they rip off authors. I’ll see if I can get it published in some form.

Dennis, nope — nothing so simple.

JMG

It is disconcerting how easily mind slips back into binary thinking. I think responsibilty is to prioritze longer meditation. Though my challenge is, in the context of the recent conference on mental health i attended, that the binary appears to exists in real time. It does look at first glance appear that attendess are either strictly politically correct, adhering to beureaucratic rule that sucks the money from frontline, or they are openly rebellious. That said, I did meet someone who presented themselves as a bridge crosser, and perhaps might elect to recover the weapon. We will see

Following up on Bliss’s comment, if you do decide to self-publish it JMG, it doesn’t have to be distributed to Amazon. I have used Ingram Spark as the hub of my print-on-demand self-publishing and you get to pick which outlets they distribute to, which means you can uncheck that Amazon box and have it show up literally everywhere else. There are ebook distributors who do the same (Ingram Spark may do ebooks too I just haven’t checked). For example, draft2Digital will distribute everywhere except Amazon. If the publishers aren’t interested, it’s rather easy to make the book available to all the world outside of that one site., Marketing it is another story.

I realize this question is a bit late in the weekly cycle, but I’m wondering if the “unhealing wound” that is located euphemistically on the inner thigh, which a spear fits neatly into, doesn’t suggest that the Fisher King is either a female or more probably that he expresses a feminine aspect in need of a masculine reconciliation to make him whole?

It would be interesting if it referred to a differently-polarized body, too, for example his etheric or mental body that is polarized deceptively and needs an active element to heal. I don’t think that’s what the original myth had in mind, but it certainly works with regards to personal wastelands. “What is the meaning?” seeks a masculine mental element, though if the meaning is posed in words or clear symbols it would be a typically-polarized feminine body that receives it on the astral.

Viewed as the land in need of the etheric force that may have been directed via the temple technology, the land could have been envisioned as a masculine king that needs the active etheric feminine to heal. Just speculating out loud here.

@John Michael Greer and Kyle

Thanks for both of your comments.

This would be an interesting topic to read an essay about some time. (The self publishing/amazon(?) topic.)

To me it seems like the Wagner series might be a good fit for Inner Traditions based on their other books on music by a variety of authors.

Annonymoose @#10 wrote: ” The transgender movement focuses on getting people who cannot control their sexuality to castrate themselves, whether metaphorically or literally;”

Lately I’ve been noticing lots of signs around here advertising “junk removal.” 🙂