At the end of the last thrilling episode of our journey through the tangled wilderness of The Nibelung’s Ring, Richard Wagner, fleeing from the kingdom of Saxony with a price on his head, had just reached safety in Switzerland. There he would remain, scraping by on the money he could make from writing and trying to dodge debt collectors, while laboring away at a gargantuan tetralogy of operas that nobody was interested in producing. It was a difficult time for him, and that turned out to be one of the best things that could have happened.

This is a common experience for a certain kind of clueless young intellectual. I can say this with some confidence because I went through it when I was in my twenties. It can happen any time you get chucked out of a comfortable situation in which all your bills are paid by other people, and suddenly have to keep yourself fed, clothed, and housed by your own efforts. It’s one of the more effective ways to shed the kind of silly beliefs about life that become fashionable among those who don’t have to worry about where their next meal is coming from.

In my case, the end of my first stint at college and the beginning of my marriage did the trick. Wagner, typically, did it on a grander scale than most, by leading a failed revolution, being dismissed from his comfortable job as Kapellmeister to the royal court of Saxony, and becoming persona non grata in most of the potential markets for his skill set. The results were similar, however, as they generally are: the clueless young intellectual has to pay a little more attention to realities and a little less attention to abstract notions about realities, and becomes a little less clueless in the process. There’s usually some amount of whining involved—I’m embarrassed to say this was true of me—and here, too, Wagner did it on a bigger scale than most.

Very often, though, what happens is that somewhere in there, usually when the whining trickles away into silence and the not-quite-so-clueless young intellectual realizes that nobody else in the world is listening, an idea, a teaching, a book, or some other mental stimulus shows up, and jolts the intellectual out of the mud wallow he’s dug for himself. That happened to Wagner, too.

His reaction was, surprisingly enough, no more grandiose than most. In his case it was a book that gave him the necessary jolt; he proceeded to study that book with the kind of passionate intensity teachers wish their students would demonstrate now and then, and his letters show that he grasped what the book had to say more completely than most, but that’s not uncommon at all in such situations. From that point on, though Wagner didn’t precisely change his ways—he kept on borrowing money and not paying it back, for example—he flung himself into work with renewed vigor, and the tetralogy shed its facile Feuerbachian optimism to embrace a richer, more tragic, and more realistic view of things.

The book that did the trick for Wagner was Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Representation) by Arthur Schopenhauer. Wagner was far from the only person in his time to be shaken to the core by Schopenhauer’s work; it had an immense impact across the cultures of Europe and the European diaspora. Art, literature, music, and popular culture all echoed with the impact of Schopenhauer’s thought. The only field in which it made no impact at all was the one that mattered to Schopenhauer, which was philosophy.

To understand the Schopenhauer phenomenon, it helps to step back a little and recall the dreadful predicament that assailed European philosophy in the wake of Immanuel Kant. Building on two centuries of hard work by previous philosophers, Kant showed with ruthless clarity that nearly everything we think we know about the world is secondhand guesswork. There really is a world out there—that much he also showed—but our perceptions of it have to go through three filters: first, the filter of the senses, which only pick up on a tiny fraction of what’s happening out there; second, the filter of the nervous system, which folds, spindles, and mutilates the input of the senses so that it can be processed by the mind and third, the filter of the mind, which is so packed with genetic, cultural, and personal interpretive schemes that it’s a wonder that any information about the world gets through at all.

As I noted two weeks ago, every philosophical tradition makes this discovery sooner or later. In healthy, mature traditions, after a period of lively debate that shows that, in fact, we really can’t know that much about the universe, philosophers turn their efforts away from grand schemes about the nature of everything and refocus on how to live in a world where the nature of everything is exactly what we can’t know.

The focus of the resulting philosophies varies from tradition to tradition. In China, where the decisive turn appears in the writings of Lao Tsu, later philosophy focused on social and political life, seeking to solve the problem of how human beings can live together in relative peace. In India, where the turn is already evident in the Upanishads, later philosophy focused on mysticism and the quest to live in harmony with the Divine. In Greece, where the turn took place during the lifetime of Socrates, later philosophy focused on ethics and explored ways for the individual to live in harmony with himself.

What direction Western philosophy might take in response to the same shattering discovery of the limits of the human mind is anyone’s guess. It may turn out that our philosophical tradition is the exception—that instead of dealing with the challenge, as other philosophical traditions have done, it will plug its eyes and ears with its fingers, chant “La, la, la, I can’t hear you!” at the top of its lungs, and continue to sink into the mire of incoherence and uselessness until it vanishes from sight. As I mentioned in an earlier post, however, there have been a few noble exceptions to that habit, and the most influential of them was Arthur Schopenhauer.

A few biographical details may help. Schopenhauer was born in 1788 to a wealthy businessman and his ambitious wife in what was then the tiny German-speaking city-state of Danzig and is now the Polish city of Gdansk. His parents gave him a world-class education, sending him to study in France and England so that he would be fluently trilingual and giving him ample support in his intellectual development, though that and a fat trust fund were nearly the only benefits he got from them. A troubled, unhappy child, he grew up to be an exceedingly difficult person, though the only thing he had in common with Wagner was arrogance.

He graduated with a doctorate in philosophy in 1813 with a dissertation titled On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, which picked up where Kant left off and set out to answer a deceptively simple question: how do we know that a statement is true? What gives us sufficient reason to say that such-and-such is the case? It was a bravura performance, but he was just warming up. He spent the years from 1814 to 1818 in Dresden, then a center of intellectual activity, writing at a feverish pace. The result, The World as Will and Representation, set out to make sense of human existence from the perspective Kant had opened up.

He had a secret weapon, and it’s one that very few other Western philosophers since his time have ever taken up. In his time the riches of Asian philosophy had just begun to find their way to intellectuals in the West, where (like Schopenhauer) they were embraced eagerly by people in nearly every field of thought but philosophy. To this day most Western philosophy prances about pretending that nobody east of the Jordan River ever had a deep thought. Schopenhauer was the great exception. He had a copy of the first European translation of the principal Upanishads, the fundamental texts of Indian philosophy, and took them just as seriously as he took Plato or Kant. That gave Schopenhauer access to a much richer body of thought than his rivals, and helped make The World as Will and Representation the astonishing work that it is.

So Schopenhauer published his masterwork, and waited for the world to congratulate him. It didn’t. Sales of the book were extremely slow. He moved to Berlin to launch a career as a university professor, and failed. After a while he settled in Frankfurt, where he lived alone except for a succession of pet poodles, took out his frustrations by squabbling with his neighbors, patronized the local sex workers and the best restaurant in town, and played the flute for an hour before supper every day.

The philosophical world never did pay him the least attention. After the collapse of the 1848-1849 revolutions, though, a great many formerly clueless intellectuals who got put through experiences similar to Wagner’s suddenly found that Schopenhauer made a lot more sense than what they had been reading. In the decade before his death in 1860, he finally got the acclaim he’d waited for all those years. From then until the outbreak of the Second World War, he was an extraordinarily influential figure across the spectrum of Western intellectual culture; if you know Schopenhauer, you can find references to his work all through the literature of the time. (His fingerprints are all over H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction, for example.)

One reason that WWR (as we’ll call Schopenhauer’s main book from here on) was so influential is that it’s written in almost superhumanly clear and readable German. Schopenhauer’s exposure to French and English prose had cured him of most of the bad habits that make so many German writers a chore to read, and he used lively metaphors and ordinary vocabulary in place of the tortured Latinisms and labored seriousness that stands in the way of understanding so many German philosophers. The English translations I’ve read never really catch that, but then it would take a writer as good as Schopenhauer to translate his prose into equally vibrant English, and such writers are in short supply. Nonetheless the existing translations are quite readable—much more so than even the best translations of Hegel, just to cite one obvious example.

Yet the great strength of WWR is its content, not its style. As noted already, Schopenhauer took Kant as his starting place. Here’s the opening passage of the book:

“‘The world is my representation’: this is a truth valid with reference to every living and knowing being, although man alone can being it into reflective, abstract consciousness. If he really does so, philosophical discernment has dawned on him. It then becomes clear and certain to him that he does not know a sun and an earth, but only an eye that sees a sun, a hand that feels the earth; that the world around him is there only as representation, in other words, only in reference to another thing, namely that which represents, and this is himself.”

With this, all the handwaving about intellectual intuition, all the claims that certain gifted people can know for certain the direction of history and the inner workings of the Absolute, falls to the ground in a smoking heap. What remains is this: what can we know about ourselves and the world that we seem to be living in, given that all we have to go on is a jumbled mess of secondhand representations? How should we then live?

Schopenhauer starts by examining our experience even more closely than Kant did. Is there really nothing we experience directly, without representations getting in the way? There’s one thing, and you experience it at every moment.

Move your hand. Now move it again. Notice that you don’t have to tell it, “Hand, move!” Nor do you have to imagine it moving, or come up with any other way of representing the movement to your hand. You just move it. The will is the one thing we encounter directly, without some kind of representation getting in the way. (We can create representations of the will—the word “will” is an example—but those representations are not the same thing as the act of willing.)

So our own will is the one thing we encounter that isn’t just a representation. Fair enough, says Schopenhauer. What happens if we assume, for the sake of argument, that this is true of everyone and everything else? What if we take our own experience of willing as our one encounter with the world as it actually is, our only access to the thing-in-itself beyond all representations?

What happens then is that the world begins to make a kind of sense very different from the one that Hegel tried to impose on it. First of all, the will doesn’t think—thinking is the art of juggling with representations. It doesn’t feel—feeling is the experience of reacting to representations. It doesn’t remember—memory is the process of comparing present representations to past ones. The will does none of these things. It simply acts.

Second, it can succeed in its acts or it can fail. When does it fail? When something interferes with it. If will is the essential nature of things, then what can interfere with will? Will. So the will can be in conflict with itself—and that means, in turn, that the essential nature of things can be in conflict with itself. It can trip over its own feet. Out the door, in other words, go all those attempts to define the essential nature of reality in terms surreptitiously borrowed from the Christian god. Out the same door go Hegel’s attempt to claim that the Absolute is unfolding in historical time in some wonderful direction that he can predict.

Third, what happens when the will fails? It reacts to its failure. You notice that there’s a rock in the path when you stub your toes on it. The “Ow!” that results is the basic form of the act of consciousness. We see only those things our vision can’t penetrate; our sense of touch can only tell us of things that resist the pressure of our bodies. So will is how we experience what actually exists, and consciousness—the ability to create representations—derives from it. Since consciousness is secondary and the product of failure, we can never know the world perfectly.

Fourth, since the will can only be conscious of what frustrates it, there is something essentially tragic in existence. Schopenhauer, being the person he was, emphasized that very powerfully. He admitted that someone who didn’t have his pessimistic outlook could rise above the tragedy of existence and affirm the universe with courage and joy—but that wasn’t something he himself was able to do, and he admitted it. It’s been said that every philosophy is an autobiography, and that’s certainly true of Schopenhauer; his own deeply unhappy life is on display here. It took others—notably the Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo, who drew extensively on Schopenhauer’s thought—to embrace that possibility and point out that the whole universe is in some sense an eternal child playing an eternal game in an eternal garden.

Fifth, and crucially, there were three ways to deal with the tragic nature of existence. One is the way of affirmation just mentioned. The second is the way of negation, in which the will negates itself and enters into peace: in essence, the way of mysticism. These two are accessible only to the few. For the many, however, there is a third way, which is art. All the arts—music, painting, poetry, dance, sculpture, fiction, you name it—raise consciousness above will. When you’re looking at a painting, listening to music, reading a novel, or what have you, your will is set aside for the time being; you are attending to a sequence of conscious states that have nothing to do with you, your needs, your desires, or your fears. This allows the will to rest and experience that rare (to Schopenhauer) commodity, joy.

These are the ideas that burst over Richard Wagner like a thunderstorm in 1854, when he first read WWR. They caused him to reshape his entire conception of the Ring cycle. One of the things that made this reshaping so fascinating is that he had already begun composing the music for the first opera, The Rhinegold, in late 1853. Thus the reshaping process unfolded while he was composing. That first opera was largely Feuerbachian in its structure and meaning, though Schopenhauer’s insights began to show themselves in the last of its four scenes: Alberich, the Nibelung dwarf who was originally slated to be a mere villain, achieves a tortured majesty in the scene where Wotan takes the Ring from him, rising to a moral stature above that of the god, and the seemingly triumphant music with which The Rhinegold closes is shot through with bitter ironies and the first foreshadowings of impending doom.

The Valkyrie and the first two-thirds of Siegfried take much of their complexity from Wagner’s ongoing struggle to integrate Schopenhauer’s insights and to reach past Feuerbach’s focus on politics and society to the deeper existential and psychological dimensions that Schopenhauer had opened up. Then came a hiatus. It became clear to Wagner exactly what was going to come of the dream of a brighter future that he’d gotten from Feuerbach. After seriously considering suicide, he set the Ring aside and worked through the matter in the only way he could, by composing two more operas.

I don’t think there are any operas in the entire history of the genre more different than the tremendous celebration of life and love that is The Mastersingers of Nuremberg and the even more brilliant renunciation of existence itself that is Tristan and Isolde. That musical comparison of the two options was what Wagner had to do before he could follow his vision all the way through. Only then could he allow the Ring to end the way it had to end; only then could he let Siegfried, the Man of the Future, the ultimate Feuerbachian hero, become the total moral and personal failure that he had to be.

We’ll leave Wagner here, penning the last triumphant notes of The Twilight of the Gods, and proceed two weeks from now to the first of the operas themselves. After the last of the Ring operas, we’ll return to him, and set the stage for his final attempt to resolve the terrible conflict at the heart of his creative vision: the “fifth Ring opera,” Parsifal. In the meantime, I’d encourage any of my readers who haven’t done so already to download a copy of the librettos of the first two operas here. The orchestra is warming up, the singers are putting the last touches on their makeup, and the curtain is about to rise.

After ruining many of the Grimm’s fairy tales, I can’t help but wonder what if would be like if Disney decided the remake the entire Ring cycle as a 90 minute animated Cartoon. I am sure the contrast between it and the Bugs Bunny cartoon version would really show where we are at as a society and civilization.

John–

Would Kether, as the first emanation, therefore best be described as pure will, rather than pure awareness, if consciousness is derivative of will? I have generally seen Will associated with Geburah, though that may be referring to a lower level of will, as opposed to Divine Will

I also recall Steiner describing will, intellect, and feeling as something of a triad of functions, but they were represented (!) more as coequal, rather than one being primary over the others, and he expressed a need for balance among them. I may be confounding concepts, however, due to similar terminology.

>Some conflicts of the will produce a louder “Ow!” than others.

So, um, who or what is willing that rock?

This just further confirms for me that I need to add Schopenhauer to my reading list – I’ll probably find a German edition on archive.org – I believe he was a significant influence on the early work of Thomas Mann, too. I wondered what Goethe thought about Schopenhauer and a search turned up this article which also revealed that Goethe was friends with Schopenhauer’s mother.

Clay, now that’s a chowblowing thought if ever there was one. Bleah.

David BTL, as I see it, at least, Chokmah is will and Binah is awareness; Kether is pure being, which we cannot perceive except through will or awareness. As for Steiner, yes, that’s very much what he was saying, but he was an eager participant in the attempt to get past Kant — more subtle and thoughtful than most, but he still didn’t accept the implications of Kant’s work and so didn’t grasp what Schopenhauer was doing.

Other Owen, nah, you’ve got it the wrong way around. Will doesn’t belong to anybody. Everybody and everything is an expression of will. As Dion Fortune liked to put it, “God is pressure.”

KAN, they’ve got plenty. Schopenhauer had a huge impact on most German writers for a good century and a half after WWR first saw print; Hesse, for example, has Schopenhauer’s influence practically on every page. (Steppenwolf is the story of a man going from Schopenhauer’s pessimism to the way of affirmation, for example.) EDIT: I went looking and found a source for WWR in just about any format you prefer, here:

https://onemorelibrary.com/index.php/en/languages/german/book/moderne-westliche-philosophie-181/die-welt-als-wille-und-vorstellung-2866

For those readers who have some ability to read German, here is a parallel text version (original German side-by-side with English translation) of the libretto of Das Rheingold: https://archive.org/download/DerRingDesNibelungenPart1DasRheingold/Der%20Ring%20des%20Nibelungen%20-%20Part%201%20-%20Das%20Rheingold.pdf

And here is the libretto of Die Walküre in the same format:

https://archive.org/download/DerRingDesNibelungenPart2DieWalkre/Der%20Ring%20des%20Nibelungen%20-%20Part%202%20-%20Die%20Walk%C3%BCre.pdf

it will plug its eyes and ears with its fingers, chant “La, la, la, I can’t hear you!” at the top of its lungs

This does seem to be the preferred method of the West. Maybe in a few thousand years we’ll see the hidden virtue of it, but right now I’m not overly enamored.

What is the best English translation of Shopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation?

I put a copy of WWR on hold today. Strangely only two editions in the whole system. In my slow research into Viennese art & music at the turn of the century he has come up several times. It’s time.

Action is equated with wholeness by Arthur Young in his Rosetta Stone of Meaning. Another great Arthur. If I recall correctly, Schopenhauer talks about suspending the Will and rising to the level of pure knowledge., which you mention with the acts of affirmation, negation, and art. Affirming the universe is a bit confusing to wrap my head around practically, Maybe it is the act of living your life while elevating yourself above the Will? In other words, to be aware of the Will while it’s willing as much as possible? Negation of the Will might be the act of discerning what is not you at all times? In other words, distancing yourself from the tragedy of daily existence and saying “that is not me”. Thanks for the post JMG.

Dear JMG, this is one of your best posts.

I can recall a similar episode earlier in my career. All excited about peak oil, during the heady years of both your blog and the international movement, I did a masters degree on it. No one of course was interested in the findings, nor was there any great career path in it. So flat on my face in a cold world I landed. I was lucky enough, and hard working enough to rework my understanding of limits in another, more practical field, where I have stayed ever since. But the lesson remains – if you think you’ve found something exciting and determinative on the habits and patterns of nature, you haven’t. Even if you have, people probably won’t like it.

I also agree that if such a translation, that portrays the positive side of Schopenhaur’s thought, it would be great. I think for it to sell you’d have to entitle it “The Plato Killer” or something similar 🙂

WWR is listed as The World as Will and Idea on Project Gutenberg.

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/38427

Apparently there is a dispute of the best translation of Vorstellung. From Wikipedia

“There is some debate over the best way to convey, in English, the meaning of Vorstellung, a key concept in Schopenhauer’s philosophy that is used in the title of his main work. Schopenhauer uses Vorstellung to describe whatever comes before in the mind in consciousness (as opposed to the will, which is what the world that appears to us as Vorstellung is in itself). In ordinary usage, Vorstellung could be rendered as “idea” (thus the title of Haldane and Kemp’s translation). However, Kant uses the Latin term repraesentatio when discussing the meaning of Vorstellung (Critique of Pure Reason A320/B376). Thus, as is commonly done, one might use the English term ‘representation’ to render Vorstellung (as done by E. F. J. Payne in his translation). Norman, Welchman, and Janaway also use the English term ‘representation’. In the introduction, they point out that Schopenhauer uses Vorstellung the same way Kant uses it — ‘representation’ “stands for anything that the mind is conscious of in its experience, knowledge, or cognition of any form — something that is present to the mind. So our first task in The World as Will and Representation is to consider the world as it presents itself to us in our minds.”[9]”

Dear Mr. Greer,

I just finished enjoying your essay, and checked http://www.gutenberg.org. They have all kinds of translations of the works of Arthur Schopenhauer in expired copyright form available for free download. Just go to the website and load his name into the search label.

Thank you for keeping your blogspots up and running. They are a place of sanity for me.

Elizabeth Ann Kennett

>Other Owen, nah, you’ve got it the wrong way around.

Is will even higher than God? Or is literally everything, God’s will?

>I can’t help but wonder what if would be like if Disney decided the remake the entire Ring cycle

Don’t give that crowd an idea they can’t handle. Only chaos will ensue.

World as Will and Representation (WWR)

Okay, so I can kinda make some sort of sense

Out of Mr. Schopenhauer’s great treatise, yep.

Not enough to classify every other doggone

Philosopher’s works in relation to it, or even

Psychological philosophers (or the inverse) like

Viktor Frankl, but following directly on Mr. Kant,

WWR makes MUCH more sense than, say Hegel,

Or that awful man whose work my college taught,

Some sort of knuckle-dragging materialist whose

Name I can’t recall now. But, really, I’m happier

With the Tao Te Ching (which I’m told says much

The same thing), or some of the later Greeks, who

Were better tempered, if not perhaps so clear as

Mr. S., who didn’t get the respect he likely deserved.

John–

“The point of the dance is itself” is a maxim I was given by Whomever She May Be nearly ten years ago and is one with which I continue to struggle mightily. This struggle is all the more highlighted by Schopenhauer’s presentation of existence as frustrated Will. It can indeed be a challenge at times to fathom a purpose in being if frustration and pointlessness are the only things on the table.

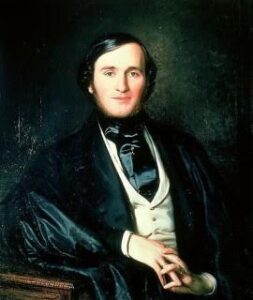

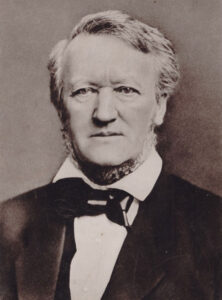

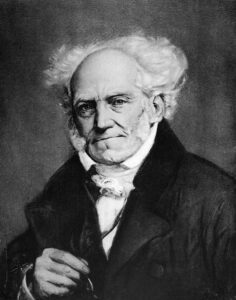

Hi John Michael,

It’s astounding what images can reveal, and yes, to the casual observer of the painting, the young Richard appeared insufferably smug. It’s been remarked upon elsewhere that inexperience can lead a person to believing that they’re smarter than everyone else. The belief ain’t true though, and perhaps this is what was meant by the term ‘mistaken belief’? His much later image revealed more balance to his features, life can do that to people. Far less hubris there in that face.

As to the old grouch of Frankfurt, if you look closely enough at the older depiction you’ll notice that his right eye is opened wider than his left, which is suggestive of a lack of balance within his personality. Last I checked, nobody has suggested that you or I are the old grouch of (insert location here)… 🙂 Interestingly, the set of his mouth and head is suggestive to me of a person who is perpetually dissatisfied. I’ve actually met people who pull that trick, and I have a hunch they do so as a form of motivation for others to appease them – although they’re never pleased, so the effort to meet the high standards are not worth it.

Have you ever noticed that Mr Lovecraft has quite a small mouth relative to the overall size of his face? His facial expression is rather tense looking, and it makes me wonder if his personality reflected that emotional state?

The Rhinemaidens looked like a lot of trouble to me, and in threes. Too rich for my tastes. 😉

Did not Dion Fortune make a rather astute observation upon the subject of magic and will? There’s enormously good advice in those words too, for those who have the care to listen.

As to your mention of the eastern farmland last week, you’re probably right. There are always unseen currents going on under the waves. Did you notice the interest rate drop? I did mention at the beginning that they’d stuff this up.

Cheers

Chris

What I love about the World as Will and Representation is that it starts from our direct experience and winds out from there in explicit detail, with helpful metaphors as well. You can follow Schopenhauer’s line of thinking very easily as long as you’re paying attention. It’s not pretentious and impenetrable like a lot of other modern philosophy.

I’m trying to go for the way of mysticism to negate the problem of existence. It’s unspeakably difficult. The other ways are easier and more innate to me. I definitely have that schopenhauerish pessimist in me, and the aurobindish optimist as well. Well, I’ll play the game as long as it goes.

Will creates consciousness, body and mind. Body and mind pass away. The will remains. The will creates new consciousness, body and mind. And so the cycle continues.

Hi JMG,

Hoping all is well with you.

I was able to order a “Used-Good” copy of the following for under $20. It will arrive slow boat to China — weeks. It looks REALLY good.

Annotated Ring Cycle: The Rhine Gold (Das Rheingold)

by Frederick Paul Walter

Illustrated

2021

ISBN 1538136686

I have been looking for Cliffs Notes, which doesn’t seem to exist — I have looked for the next best thing. It’s been hard to find, say, 7th grade level. I need the story idiot-proofed. It is the funniest thing: I have not been able to take in but a little at a time — maybe it is just so new (to me), or my advanced age.

To pass time, waiting for the election, I have been trance-dancing to Olivia Newton-John’s “Magic✨🎤🎹🎸🥁.” The lyrics are oddly appropriate, as I wait-the-slow-wait until I get to the voting machine and type Yes for Tramp.

By the way, “liberal” (having no sense of morality whatsoever) talk-show hosts — the vast majority (if not every last one of them) — spend 99.9% of their precious air-time bashing Tramp🤗🤩. Tramp-bashing is their religion✝️🔯💰. They CANNOT NOT talk about Tramp. They are mentally-ill obsessed. I doubt they can come up with anything OTHER than bashing Tramp. I don’t know how they devise any new material. On day after the election, November 6, the hosts will fall off a cliff, having nothing to talk about. Heaven forbid they respectfully ask a Tramp-supporter, “Why do you like Tramp so much?” or “What is it about🦎KomodoDragonHarris🦎you dislike so much?”

Also, we need to spread around the assassination attempts evenly between Republicans and Democrats. Next time is “a particular Democrat’s” turn. What is so special about her? Just sayin’. (It is not like everyone isn’t already talking about the subject of assassination, including every newscaster (so much so as to feel like vomiting🤮hourly) (I am tired of gagging).

💨Northwind Grandma💨🇺🇸🤗🎹

Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

Roy, thank you for this!

Cliff, my guess is that Faustian culture, to use Spengler’s name for it, will suffer the fate of its namesake. A few thousand years from now it will be a dim, frightening memory.

Anonymous, good question. I’ve only ever studied the translation by E.F.J. Payne, which is capable but fussy.

Justin, delighted to hear it. It’ll be a trip.

Luke Z, Arthur Young — oh my. That’s a name I haven’t heard in a while; I studied The Geometry of Meaning years ago. I should see what I can find of his works now. As for the way of affirmation, no, that’s the way of affirming the will itself — of embracing the will in all its tragedy and self-contradiction and willing it yourself. Nietzsche called it the great Yes-saying to life.

Peter, thank you! As for Plato-killing, Schopenhauer actually finds a place for Platonism within his own philosophy, and manages to make it make more sense than Plato ever did. His work really is a tour de force.

Siliconguy, yep. He’s been popular long enough that the older translations are long since out of copyright. As for Vorstellung, it really doesn’t have a good English translation, but I think “representation” is better than “idea.” The verb vorstellen comes from vor-, cognate to English fore (as in “before” or “fore and aft,”), and stehen, cognate to English stand; it means “to place before, set up before.”

Elizabeth, PG is a good source for most of the old philosophers — thank you for this.

Other Owen, to Schopenhauer that term “God” is a somewhat clumsy mythological description of the will.

Clarke, ha! Thank you for this. “Knuckle-dragging materialist” is a keeper.

David BTL, the frustration and pointlessness Schopenhauer found on the table were things he brought to the table himself. Our value judgments (and “frustrating” and “pointless” are value judgments) belong to us, not to what we’re judging.

Chris, that’s why I included their photos. Lovecraft — well, yes. We’re discussing a man who spent his entire life being terrified by salads. (Among many other things.) Both his parents died in an insane asylum, so his cosmic paranoia wasn’t completely without basis…

Enjoyer, the way of affirmation is the one that works for me, but do what keepeth thou from wilting shall be the loophole in the law!

Northwind, thanks for this. Of course the hosts can’t ask — they think their job is to tell everyone what to think, not to find out what other people think all by themselves! The irony is that they’re probably doing a better job of supporting Trump than his most enthusiastic fans — since he’s all they can talk about, they keep him front and center in the public imagination, with predictable effects.

I should have added, I wonder if Schopenhauer, having the ability to read it (which he didn’t have) to use Fortune’s approach to theodicy, and the way she deals with limits, negative evil, and positive evil, provides a way around the sadness and tragedy that Schopenhauer reached. In a way, I see resolving that challenge in your own mind, once you’ve realised it, as part of the initiation of the nadir. You reach the limits of the universe, and can realise there’s a certain pointlessness or lack of purpose to it, and then you face a choice.

JMG,

Sorry if I’m being obtuse. What is the way of affirmation, practically speaking? Or alternatively, what is the difference between the way of affirmation, and of the “great Yes-saying to life”/way of affirming the Will itself? I think there’s a gap missing in my understanding of the way of affirmation. Thanks!

Sri aurobindo has popped up now twice in quick succession. I’ve been reading psychic self defense cause frankly meth addicted bestie seems to me had opened a lot of doors and I’m trying to understand what kind of influences there are ‘out there.’ The chapter on non-humans, elementals mainly, has really gotten to me. When she describes thought forms taking shape, mothers creating guardian angels for their kids as they die, her own resentful brooding creation of a werewolf. Well I think my mother made me like an enraged reverse of a guardian angel when I was about 13 and couldn’t developmentally fulfill the needs she expected me to for her. just after I read fortuna learning she had to reabsorb it (not cut any cords as it’s cord was already cut so to speak), well YouTube sent me to someone reading aloud Sri Aurobindo who had all kinds of helpful advice about Thought Forms and then an anecdote where someone learned ‘the trick’ of dealing w self-generated manifestations of absorbing them back. (And I was not reading fortuna aloud to my phone speaker algorithm spy!) So seeing him turn up again as someone who can say the great Yes to the universe and the complicated mess of interacting variously frustrated wills makes me like him twice over. I have a bigger question about elementals and non-humans/deva kingdom i was trying to word for magin Monday but i ended up writing a long set-up backstory and then finally went to sleep. I’ll try again before next week. I sent my methy bestie the quote about art allowing someone to think of something that is not oneself and the benefit of that in resting the frustrated will. His life has gotten to be perpetually frustrated and carpentry works as art which gets him out of the constant awareness of that frustration (made worse by a trauma and drug induced schizo way which makes him the center of everything, more than his past normal). I loved that section, ‘Fifth’ about the base layer choices for how to deal with the logical steps 1-4. Thanks.

I would love to listen to Nicholas Berdyaev, Arthur Schopenhauer and John Scotus Erigena in a room, while plied with beers. To go with hermitix podcast rules. I’d include Wagner but I’m partial to Mahler or Bach. Thanks for this. Another fine piece. Is it fair to say Wagner had no other really deep influences besides Fuerbach and Schopenhauer? And wouldn’t your guess make Faustian culture follow a kind of Egyptian fate, except into intellectual as well as physical oblivion? Not even a legend? Maybe just a cautionary myth, perhaps!

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Mariette (Miow)’s surgery on 20 September be a success. May she make a full recovery and regain full use of her body. May she heal in body, soul and mind.

May The Dilettante Polymath’s eye heal and vision return quickly and permanantly, and may both his retinas stay attached.

May Tyler and Monika’s newborn baby Isabelle, whose bowels were not moving properly at birth, and who as of 9/16 has not experienced a bowel movement, be blessed with a well functioning digestive tract and be free of colic going forward.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Tyler and Monika’s newborn baby Isabelle, whose bowels were not moving properly at birth, be blessed with a well functioning digestive tract and be free of colic going forward.

May Falling Tree Woman’s son’s girlfriend’s mother Bridget in Devon UK, who has recently started to sit up and converse after more than six weeks of bedridden tracheotomy following a life-threatening fall from a horse, be blessed and healed and returned to full health.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Heather’s brother in law, Patrick, who is dying of cancer and has dementia, go gentle into that good light. And may his wife Maggie, who is ill herself, find the strength and peace she needs for her situation. (Update on Patrick’s condition here)

May Neptune’s Dolphins’ husband David, who lost one toe to a staph infection last year and now faces further toe amputations due to diabetic ulcers in his left foot, be blessed and healed, and may the infection leave his body for good.

May Rebecca, who has just been laid off from her job and is the sole provider for her family, quickly discover a viable means to continue to support her family; may she and her family be blessed and sustained in their journey forward.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

This discussion about Schopenhauer reminds me of a contemporary philosopher who is inspired by Schopenhauer’s philosophy. Bernardo Kastrup. He’s been trying to fight against materialism in academic philosophy.

I suspect he personally has quasi-esoteric views but tries to keep it on the down low. He’s alluded to ‘daimons’ and unembodied consciousness before.

Anyway, here’s what he said about Schopenhauer:

“Had the coherence and cogency of Schopenhauer’s metaphysics been recognized earlier, much of the underlying philosophical malaise that plagues our culture today—with its insidious effects on our science, cultural ethos and way of life—could have been avoided.”

I think you would agree with such a statement, John. However, I have some criticisms of Bernardo, he kind of reads his own philosophy into Schopenhauers. I guess that’s a common thing in philosophy, after all, Plotinus considered his philosophy to just be Platonism but today we consider it to be different than Plato’s philosophy. Philosophers always want to draw legitimacy from those who came before.

Also, Bernardo certainly has a very western-centric progressive view of history and tends to be pretty bad when it comes to his political takes.

I actually think a conversation between the two of you about metaphysics and the history of scientific materialism and occultism would be very interesting, granted that it steered clear of politics, especially the Ukraine war. If the topic moved into that territory, it would go south pretty quickly. Anyway, he has a blog as well as a website where people can submit articles. He’s had Patrick Harpur on there. If you are interested I can link his website to you.

Well, this is exciting! Wonderful summary of Schopenhauer and what he meant to Wagner. As we rub our collective hands in preparation for diving into the Ring operas themselves, you recommend downloading and reading the libretti of the first two operas. Good idea, but perhaps people might also be encouraged to do some listening? As you suggest (and many others have noted) Das Rheingold can sound a bit forced and pedestrian — no doubt for the reasons you suggest (the conflict between Wagner’s conscious level enthusiasm for Feuerbach and what his unconscious was already telling him.about the essence of the human condition — reading Schopenhauer of course brought those notions into his consciousness.). And one does have to get to know it a bit, both to understand the story and to fix the musical motives (the “leitmotifs”) into one”s head — those will be worked and re-worked right through to the penultimate chords of Die Gotterdammerung. But Die Walkure strikes the listener (at least this listener) as one of the great breakthroughs in the history of music, indeed of all art — comparable to the Marriage of Figaro and the Eroica: here is something the likes of which have never been heard before, something that goes to the heart of what it is to be a human being. The greatest recording I have ever encountered can be listened to in its entirety here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MXSTNZ6yKbc. It features a roster of the greatest Wagner interpreters of the mid-20th century; the recording itself was produced in 1959 by the inimitable John Culshaw at the dawn of Decca’s golden age.

One minor quibble: you wrote that “The only field in which (WWR) made no impact at all was the one that mattered to Schopenhauer, which was philosophy.” True, I suppose for the 19th century (if one skips over Nietzsche.). But as the great Schopenhauer scholar (and Wagnerian) Bryan Magee pointed out, “Schopenhauer was the first and greatest philosophical influence on Wittgenstein, a fact attested to by those closest to him.” And Wittgenstein for better or for worse was probably the most influential philosopher of the 20th century.

WIth regards to the western response to Shopenhauer, isn’t the entire continental school with its phenomenology a continuation of this concept, or rather an exploration of how our will and awareness interact with the physical and the attempts of consciousness to awaken to itself?

Wer here

Well JMG I’ve never read these books because I don’t have a lot of free time . I am guess a simple minded man and I never liked a lot of rich “philosophers” mulling over the meaning of everything. In my opinion the most important skills and realistic outlook are the most important, go to work somewhere instead of wasting your time.

Perhaps I am ignorant of this young intellectual suddenly thrusted into the bad world because I was never an intellectual to begin with, so I honestly don’t know what you and by proxy Wagner when into…

I’ve never been a part of any “movement” because they strike as something “engineered” by someone in order to achieve some purpose, and many people in these movement strike as someone that was paid by someone to be there, just a gut feeling of mine I understand if you don’t agree.

BTW I remember my last comment I’ve made here about Trump getting assassinated by an bomb, with what is going on with these attempts and killers appearing everywhere is it still so improbable that the RNC will have a mass murder attempt or an bomb there?

If Trump is murdered before or worse after the election (he wins) what will be the reaction to this. While I am writing this mass evacuations are taking part in Poland the south of my country is under water and it is complete chaos there good greif It is just one thing after another…

Stay safe everybody Wer

Hello John,

How do you synthesise Schopenhauer’s conception of The Will within a spiritual/occult framework? Does this not transcend benign forces that supposedly lord over us? I spoke with a Neoplatonist I am rather good friends with, and he spoke to me about how Daemons/Daimones are just instruments in carrying out desire and apply no moral judgement irrespective of the wordily consequence. A contention I have with Schopenhauer, as much as I agree with him, is that although he suggests Will takes precedent over all, he will attribute ‘The Intellect’ to the human-child and ‘The Will’ is a thing that we grow into – It would suggest a more rationale, and ordered system right?

Thanks,

Planasthai

Some idle thoughts along the way, on first reading of this post:

Yes, being out in the world without a safety net is a great reality check. I thought of Marie Antoinette being reduced to actually herding sheep for a living, and then remembered the legend that Elizabeth Tudor once said she could survive if turned out on the world in her petticoat. The clueless French queen died, a failure; Elizabeth had a long and successful reign, having learned survival in a hard school as Henry’s discarded daughter.

Hegel was the drug; Schopenhauer was a dose of Narcan. As for “old grouch” in person – how was his digestion?

For his ideas on how to deal with the universe as is – Affirmation was the way of the Stoics; negation, of the early Christians, and art, the way of Classical Greece in its heyday. I think I like the Greek ways best.

P.S. How well did Schopenhauer navigate the everyday world of people and society?

Thanks for this – I particularly enjoy your dives into philosophy.

Are the paths of affirmation, negation and creativity mutually exclusive? Many people I know that I would call somewhat happy and healthy seem to have blended these paths together in their lives: some blend of acceptance that life throws ups and downs at us, that we can chose to focus on the bright side, that meditation and spiritual inquiry can provide both solace and inspiration, and that some or many forms of creativity provide their own enjoyment and reward. I appreciate that a few people specialize in one or other of these paths, but don’t most human beings, improvising generalists as we are, stumble into some sort of blend?

Good to know also that Schopenhauer understood that his own somewhat melancholic personal disposition shaped his thinking. I’ve often wondered what would have happened in western history if philosophy had only attracted the sunny optimists with a heaping-helping of happy brain chemicals! I’m guessing those sorts of people don’t want to spend too much time over-thinking things though 🙂

I clearly need to get around to reading Schopenhaeur closely eventually.

On Platonism… Lloyd Gerson did an interesting lecture recently entitled “Taking Plato Seriously: Proclus as Exegete.” The title comes from a hostile critic of Plato who insisted that “If you take Plato seriously, you end up with Proclus.”

Again, this is coming from a place of ignorance of Schopenhaeur, so I could be way off base. But it certainly seems that Will and Representation can be understood as Life and Intellect, the second two terms of the Intelligible Triad, with the mere being that unites both Will and Representation being, um, Being, the first term of the triad. The henads and the ideas, then, are simply Wills which are prior to and vastly more powerful than our own, ultimately arising from the unimaginable source which transcends being and non-being. Of course, Being, Life, and Intellect are also known by their Hebrew names, Kether, Binah, Chokhma…

Oh, I meant to include a link to Gerson’s talk, for those interested in listening to audio lectures–

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLSNU_0L4MA&t=789s

I’ve made several unsuccessful attempts at tackling the Payne translation of TWWR. It doesn’t help that Schopenhauer begins by insisting that the reader first read Kant, or at least his principle works. This could end up with going all the way back to Plato, or maybe even the Pre-Socratics. I’ve proceeded by seeing how much I can absorb of TWWR itself without that going down that nearly infinite regress back to Plato and beyond, assigning myself a small but do-able daily dose. Consider it work on will with a small “w.” I have skipped back to the last section of Vol. 1, the critique of Kant, because that’s what A.S. seems to be recommending early on. A.S. does have a sharp wit that comes through nicely at times. All this for Wagner?

I think the way of mysticism can be scaled down, to the kind of negation of will required by those in recovery groups. I wonder if Schopenhauer was ticking away in the background anywhere in the formation of AA?

The arts seem to have been watered down in a negative way with television. People watch it for that negation of will. The other arts are different than that and still require imagination to be used in some ways.

This leads me to distraction and a point made by Randomactsofkarma in last weeks comments that I think can tie in with Schopenhauer’s famous pessimism: ” …I agree that sadness and fear can be channeled into activity, though for me, I think the activity is usually (subconsciously) intended to be a distraction.”

Distraction can be healthy to a degree. For instance in the Octagon Society work, the focus is on 15 minutes or so of intense journaling on matters of anger, shame, grief, and the like that impacted our lives. More than that ends up being counterproductive. Then it is time to move on. A distraction can be good.

When it comes to making art of any kind, and getting into that flow state. this becomes a healthy distraction, as you really start engaging with something and forget about your problems. Speaking for myself, I’ve found that when I’m not as focused on my problems, they are more likely to fix themselves as often as not, and the thing I was obsessively worrying about disappears. The healthy distraction for the creator of art, then can become a healthy distraction for the viewer, when they engage with it. The problem with TV is it leaves so little room for engagement, and the way people tend to get absorbed by it. Same with internet, if not careful.

Anyway, just some thoughts on these different paths. It also seems like that might be modes that you could play in, like a musician does. Certain times in life might call for different modes.

Hey JMG! A great post! I like very much Schopenhauer, he was one of the greatest Western thinkers, so the poorest thinkers never have forgiven him…Of course he was a mysoginist man: nobody is perfect.

Peter, that’s certainly my read on things.

Luke, I don’t recall suggesting that there’s a difference between those two.

AliceEm, you’re most welcome. That’s a difficult road you’re walking — may it turn out well for you and your friend both.

Celadon, Wagner read voraciously and stayed at the forefront of European thought; Feuerbach and Schopenhauer were just the two most important of many influences on his ideas and creative work. As for the future of Faustian culture, a culture whose core image is expansion into infinite distance isn’t likely to make old bones. Egypt had a will to permanence; Faustian culture has a will to self-immolation. Will there be cautionary stories? Oh, quite possibly, but how much of the Faustian spirit will they actually embody?

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Enjoyer, it’s almost impossible for a philosopher not to read his ideas into his sources — it all seems to follow so logically! My take on Schopenhauer, for all of that, is strongly influenced by my reading of Eliphas Lévi, Dion Fortune, and the early Taoists. I’ll consider your offer, but respectable thinkers generally shy away hard from actual practicing occultists, you know.

Tag, I certainly encourage anyone who wants to listen to the music to do so, but I won’t have a great deal to say about the musical dimension of the Ring — I simply don’t have the background. I’m mostly going to be talking about the ideas. As for Wittgenstein, so noted!

Quift, that’s an interesting point. I don’t claim to be au courant with continental philosophy these days, so I may have missed the influence.

Wer, there are certainly fake movements — the slang term in English is “astroturf,” as an artificial equivalent of something that comes from the grassroots — but there are also real ones. As for Trump, I really have no idea. I hope we don’t have to find out.

Planasthai, I take Schopenhauer’s metaphysics as a starting point, but I make a few modifications. First, it’s in no way required, or even likely, that human beings are the zenith of the Will’s capacity for reflective self-knowledge; given infinite time before us, it is certain that there will be beings far greater and wiser than we are, and we may as well call such beings by the traditional label “gods.” This being the case, religious experience — defined here as human contact with gods — is a way to stretch the boundaries of what we can know. It doesn’t erase the boundaries, especially since the results of religious experience have to be communicated to others through the lumbering mechanisms of human thought and language, but it does allow certain tentative deductions, including those that underlie spiritual practice. As for will and intellect, not at all — a newborn infant has no intellect to speak of but expresses will with great clarity; it wills to be fed, to be held, to have its diaper changed, and so on, and will let you know in no uncertain terms if its will isn’t fulfilled!

Patricia M, I don’t recall anybody talking about Schopenhauer’s digestion, but he was very fond of gourmet meals, and in a 19th-century context that probably meant he had a cast iron digestive tract.

Mark, of course. Most people are naturally eclectic; when Paul Feyerabend wrote Against Method, which challenged the idea that philosophical consistency is a good thing, he spoke for the vast majority. Philosophers have been tearing out their hair over that for millennia.

Steve, I’m very much in favor of ending up with Proclus, for what it’s worth! As for your analysis, yes, that works tolerably well within a Schopenhauerian account; rather than speaking of different wills, he’d frame the henads as grades of the Will, and in fact he does frame the Ideas in those terms, as part of his absorption of Plato into his system.

Phutatorius, you’ll notice that I didn’t ask anyone to read Schopenhauer. I think he’s readable and worth the time, but your mileage may vary; as long as you have some sense of the basic ideas, you should be able to follow along.

Justin, I’m not sure if AA was riffing off Schopenhauer or borrowing from Christian mysticism, which also tends toward a renunciation of will; it’s an interesting question. As for different modes, of course! To my mind, it’s very healthy that writers about philosophy these days very often talk about this philosopher’s or that philosopher’s account of reality, without trying to claim that one or the other is The One Right Way. Different accounts or, if you will, different maps are useful in different situations.

Chuaquin, oh, granted. We all have our bad habits and our stupidities.

Wonderful episode JMG and much to ponder! Dion Fortune’s three-fold way and the story of Orpheus (which I’ve been meditating on) has become much clearer and more meaningful!

Thank you!

Yogaandthetarot Jill C

JMG,

I’m often surprised at the lack of mention of the influence Jacob Boehme had on Schopenhauer as well as on a host of other German philosophers. Boehme, who as some have said was the first German philosopher, posited that at the root of existence was the “Ungrund”, the Godhead, which was essentially the Will, which is prior to God and the Divine Trinity. (In Boehme’s Christian terms). Within the Ungrund, which is Nothing, a Chaos, there is the eternal desire to become something – this is the fiery nature of God at the root of existence which gives way to the dynamic process of light, love, Creation.

The philosophy of Schopenhauer and of other German philosophers seem to be a de-Christianized version of Boehme. Granted, Boehme was not exactly systematic in his writings as were the philosophers who came later. His writings are not exactly elegant, and are at times impossible to comprehend, much in the same way as are some of the poems of Blake, who was also influenced by Boehme. But he does seem to have originated, in German philosophy at least, the idea of the Will as the root of consciousness and Existence itself.

“In China… later philosophy focused on social and political life, seeking to solve the problem of how human beings can live together in relative peace. In India… later philosophy focused on mysticism and the quest to live in harmony with the Divine. In Greece… later philosophy focused on ethics and explored ways for the individual to live in harmony with himself. What direction Western philosophy might take in response to the same shattering discovery of the limits of the human mind is anyone’s guess.”

I am going to guess, even though I’m not a great philosopher, that Western thought will continue to focus on Nature because that is what it has been doing so far. That is what created modern science. Also, arguably, among the three domains of Divinity, Humanity, and Nature, only Nature has not been studied in depth by other philosophies.

It is now clear that the great Western quest for complete understanding and conquest of Nature has failed. Therefore, the main question becomes: “How should we relate to Nature that we can’t fully understand or control, and live in relative harmony with it?” This will be a significant concern for future societies, as they will have to grapple with the pollution and environmental degradation left by previous generations.

With any luck, future thinkers will take a step back and adopt a more humble attitude, like that of natural philosophers and alchemists, and follow in Nature’s footsteps, attempting to imitate her. I think, you, JMG, are a forerunner of this future school of thought; you’re just ahead of the time.

https://www.alchemywebsite.com/images/AF42.jpg

Dagnabbit, Bro. JMG, – my reading, listening, and discursively meditating lists keep growing because of this here blog and commentariat, and I’ve always had a challenge with pruning. You’ve even got me listening to and watching operas. 😉

Thanks for this, JMG. On the one hand, my high-school understanding of philosophy simple does not stack up to what little we are discussing here (no surprises there). Specially important is how our modern cosmo-vision derives directly from (Hegelian) philosophy. I do think the obscurity of this fact is more or less unintended; the “don’t think, do” attitude is 100% handed down from the powers that be, but I do not think themselves are aware of how deep the rabbit hole goes.

And on a more personal note, quite the mirror you have presented us (or is it just me?). “Clueless intellectual meets life, hilarity ensues” does not begin to describe it. Yet, it is comforting to know there might be a better version of yourself on the other side of it, if only you are willing to walk the tunnel from side to side.

JMG, it makes sense. A society that always super sizes itself into Infinity and beyond, and tries to manifest that across (ahem) the whole globe, is liable to generate an impressive kickback or pendulum swing. Such a swing could well annihilate all trace of the Faustians.

JMG,

Wer makes an interesting point. Most people don’t have the time, inclination, reading comprehension skills or intellect to study the great philosophers in depth and decide which ideas to apply to their life. Many don’t think much beyond the kick-off time of the next football game, and where their next slice of pizza is coming from. Others adopt a dumbed down and consumer driven philosophy spoon fed them by such books as ” The Secret”.

But others ( in my experience these were farmers, fishermen and old school workingmen) would adopt an actual philosophy of life base on experience, church, analogies, or wisdom passed down to them by mentors or parents. Granted these philosophies may have been ultimately seeded by the great philosophers so I am not discounting their influence.

My grandfather had less than a high school education, having fled the dustbowl of Nebraska , worked picking crops in Eastern Washington and Oregon, worked building Barracks as a carpenter during WWII and ultimately becoming a small dairy farmer before retiring to spend time on my parents farm teaching me and my siblings the meaning of hard work.

His personal philosophy seemed like a kind of prairie stoicism. He advised me not to take up vices such as drinking or smoking, not because they were bad for your health or an affront to god, but because they caused a man to lose control of his own will, to become dependent on something other than his own decisions. To not worry about circumstances beyond your control and make the best of what you had . He was as happy sitting in the shade drinking lemonade as he was pitchforking manure by hand in to the manure spreader.

Many of these old-timers that I had the honor to meet and work with in that pre-internet agricultural world seemed to take a much more contemplative and philosophical approach to the world than most of the highly “conventionaly”educated people I know today, even though many of them had little education.

Elon Musk, Just had a post where he explains why he continues to work though he is worth $billions. He explains using his quest for meaning in philosophy. This starts off nicely ,but then veers off in to the ditch of interstellar travel. But partway through he drops this statement that is very relevant to todays post.

“Be careful of reading German philosophers as a teenager. It’s definitely not going to help with your depression. So reading Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, as an adult, it’s much more manageable. But as a kid, you’re like, “Whoa.”

I’m finding myself worked back sort of full circle to a repackaging of Kant. I’ve reached a point where I need to cut to the core ‘thing’ that has driven me for decades. I’ve just put Schop. V1&2 at my bed stand. The Art has moved me by, I guess, will and flowing synchronicities. I have been so amazed by the great intelligence with which I am so grateful to have been able to participate. I’ve come to realize that this ? is that which lived me through the jungles of ’75.

I don’t have time to meander. The Art is on the cusp of a new stage. I brought my study of the Tree of Life into The Art and it beckons me forward. I can’t imagine that I won’t go there, but now it will be about my own will. I need to pull the pieces together and become what you might call operational. It was all destiny as the story unfolded up to now. The pieces all fell into place – mind you I had to be kicked in the head along the way, and the scars are integral to the process.

“…there were three ways to deal with the tragic nature of existence. One is the way of affirmation just mentioned. The second is the way of negation, in which the will negates itself and enters into peace: in essence, the way of mysticism. These two are accessible only to the few. For the many, however, there is a third way, which is art. All the arts—music, painting, poetry, dance, sculpture, fiction, you name it—raise consciousness above will….” I think that I’m looking for a middle path here…

>The irony is that they’re probably doing a better job of supporting Trump than his most enthusiastic fans

Don’t forget the shadowy deep staters trying to kill him either. They’ve endorsed him with bullets.

13 Thank yous, once again, Arch druid, for this further dive into the history of ideas,

I am very intrigued by this idea or role that will can play, both philosophically and practically, whether that be in the occult realms or psychological growth and development. Otto Rank wrote about Will Therapy and influenced many of the psychologists that I have been influenced by, Carl Rogers and Stanislav Grof, to name a couple. Rank also coined the term Counter-Will, which has become a forgotten part of the history of psychology and psychotherapy. Understanding counter will has been most helpful in my many years of working in child and youth mental health and understanding human development. I have no idea if Rank was influenced by philosophers from the century before, certainly this history of ideas extends down through the years, centuries in ways I can only begin to imagine.

Always a pleasure to read this blog each week!

Long life and honey in the heart!

@ Tunesmyth –

Thank you very much for posting the housing-related prayer request for myself, my sister Cynthia and our elderly mother Dianne. If there is any way you can see to bring it to further prominence under non-health related matters, I would really appreciate it. Thanks!

Kevin

Kevin

Great essay and much to think about! For now, I just have a few fragments.

After your first Schopenhauer post some years ago, I read WWR and was surprised by his knowledge of English-language philosophers. Now I know it was his personal education, but generalized knowledge of English in his time!

When you summarize his writing about touch as the frustration of will, I immediately thought about caressing a human being, or an animal, which is not frustrating at all…

I think what Saved Schopenhauer in a way as I read this, was that he admitted he was a John in his younger years out of frustration – that his disposition caused him to make those mistakes. That he also knew that there were and are and will always will be people who never had to pay money to a prostitute, that when one has a moment of self destructive actions that they have the will to pick themselves up. Thats what saves him and his work from entering the dustbin. A lot to think and mull over.

You leave it as an exercise for the reader why Schopenhauer’s influence waned with WWII. My impression is that almost every philosophically inclined writer of the 1920s and 1930s glorified strong wills and independent minds, vilifying rules and laws (not least those of the Hebrew Bible). This may have been more directly influenced by Nietzsche than by S., but I think all the talk about will got tainted by Triumph of the Will .

Hi John Michael,

Salads? Are you serious? Hmm.

You can tell a lot from a photograph, and Lovecraft’s small mouth and narrow nose is also suggestive of someone who’d experience breathing difficulties. That may in some small way perhaps explain some of the err, how did you put it again, paranoia? Thought you might be personally interested, but I’ve read that there are some statistical relationships being noticed between: picky eating behaviour; soft foods; lack of jaw development; mouth breathing in preference to using the nose; and autism.

Have to laugh about Wagner in a sort of sad way, but he’d exhausted every avenue and possibility for forcing his will upon the rest of the world, until he could no longer ignore the simple truth: It was him all along. But to his credit, clearly he must have started out on that journey, and obviously he found something there.

I’ve been wondering about the land of stuff and the bear of late. Hmm. Oil and energy is clearly going from one to the other nowadays, and err, well, given such transfers now exist outside the purview of the western sphere of interests, do you think it may be possible that over in the land of stuff they now run a two tier economy? Obviously there are some problems over there, but for all we know, they could walk away from their currency for a new one. Most of their transactions are now digital. Hmm. It’d be a neat way for them to hedge their bets and play one groups interest off that of the others. Plus for all we know, the land of stuff may let the wests influence wane that way (and possibly also tank the same interests) without quite directly confronting the west. Dunno.

Oh, and I’m amazed that anything and everything will get chucked under the bus in order to dodge inflation for a little bit longer. The de minimis rule changes are fascinating, and turns out even the super wealthy have to kowtow, just like everybody else.

Sometimes there’s so much going on, it makes my head spin!

Cheers

Chris

Aren’t Schopenhauer Nietzsche Wagner etc just saying the same thing that Shakespeare laid out hundreds of years earlier (and others before him, including the whole western church idea of contrition)? There doesn’t seem to be anything new here, just a continuous rediscovery and justification of the same core Faustian myth. You don’t need to go any further than King Lear, Hamlet and Macbeth to understand all the guilt, psychological drama, will to power and historical depth of Faustian man. It’s all tragic, but not tragic in a Greek way (situational and fickle) but tragic in the manner of individual wills, particulars and effects through time.

God to western man has always been Will, he is just the biggest Will. But western will itself is a phantom from other philosophical perspectives.

@ Peter Wilson #22

I’ve been meaning to read more of Fortune and have some books I haven’t started yet – where does she write of her approach to theodicy, and the way she deals with limits?

Thanks,

Drew C

PS and of course thanks for JMG for this fascinating series, I favor “The Marriage of Figaro” as the peak of Faustian culture, but am enjoying the explanation of how the Ring cycle may be more of a capstone.

Out of curiosity, what did Schopenhauer say (if anything) about the issue of time? I’ve read some blurbs by philosophers and also books by Brian Greene and some other physicists and some of it makes some sense but the problem is that the science stuff (you know, like the ‘block’ universe idea) contradicts our everyday experience of time.

What I got from this ‘block’ universe is that past and present and future all simultaneously co-exist which defies what we see moment by moment.

But some of it made some sense because by this scheme if space is the distance between objects then time is the distance between events. And an event is a change in the configuration of objects and so you locate something in time by locating it in a particular configuration of objects.

But still all this doesn’t square with our conscious experience of one moment following on the heels of another and of time having a ‘direction’ for lack of a better word.

So what of Schopenhauer? Did he have anything useful or did he just add to the mystification? Because according to some of these geniuses we’re just four dimensional insects encased in this amber of the space-time continuum. But then what of free will?

It’s such a great project to illuminate German philosophy through these operas and to illuminate the operas through German philosophy.

Not knowing German, I have a question about the libretto. Is the archaic quality of the English translation (Thou rejoicest rather than You rejoice, etc) an attempt to get across German grammar or is Wagner’s language deliberately archaic?

While thou rejoicest,

Joyless am I.

Thou hast thy hall;

By chance, my bookclub (of two) is attempting to read _Atlas Shrugged_. Both of us have read it completely in our younger days, enthralled with the novel as young men often are, and this will be my third or fourth attempt to reread it in later years (having not gotten past the first screed in those previous attempts). But we’re still in the early, more readable chapters and I am reminded once more why Francisco d’Anconia–and not John Galt–is the ideal to which I would choose to aspire:

“Francisco could do anything he undertook, he could do it better than anyone else, and he did it without effort…What he meant by doing was doing superlatively.”

“[I]f one stopped him mid-flight, he could always name the purpose of his every random movement. Two things were impossible to him: to stand still or move aimlessly.”

Setting aside Rand’s worship of greed and deification of human reason, this portrayal of Francisco is to me the embodiment of Will and the effortless grace that is the ideal of the Renaissance Man. To strive with purpose. To carve one’s path through life. To imbue existence with meaning through the creative act. How does one reach for such meaning in a world bound by tragedy?

Jill, you’re most welcome.

Will, hmm! Interesting. Yes, that makes sense — and it reminds me that I really do have to study Boehme one of these days.

Ecosophian, I certainly hope Western philosophy takes up that question. It could accomplish quite a bit of good that way.

Monster, I see my evil plan is working. (Rubs hands together fiendishly…)

CR, I think a lot of people have had that experience of late!

Celadon, exactly. Europe in particular seems to have been seized by a passionate desire for self-annihilation.

Clay, I’ve met people not too different from that, and yes, there’s a folk contemplative tradition that gets far less attention than it deserves. As for Musk, oh, granted! Asian philosophy is better for teenagers. (At least it always worked for me.)

Cobo, good. There’s a middle path in all these dichotomies (and trichotomies!) — it just takes finding.

Other Owen, so far those have been very useful endorsements.

Hankshaw, fascinating. I haven’t read Otto Rank, and I think I need to.

Aldarion, good. It says a lot about Schopenhauer that he never thought of that example.

Novid, I suppose that’s one way to look at it.

Aldarion, yep. It was exactly that.

Chris, yep. He was terrified of salads, fish, cold weather, mushrooms, air conditioners, his own ancestry, and much, much more. Autistic? Very possibly so.

Will-ow, sure, if you overgeneralize it. That said, Schopenhauer was a passionate Shakespeare fan and read him in the original, so reflections of Shakespeare in his philosophy aren’t accidental.

Smith, Schopenhauer accepted Kant’s argument that time, like space and causality, were a priori categories of human consciousness. They’re not objectively real — they’re part of the hardwired structure through which we experience the world as representation. That doesn’t result in the amber-block theory, since that tacitly assumes that space or space-like dimensions are objectively real but time is not; Kant’s analysis (expanded by Schopenhauer in The Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason is that space is just as subjective as time. We cannot experience the world except through the subjective structure of space, time, and causality; to us, they are more real than anything else — but they’re still part of the equipment with which we perceive the world, not part of the world we perceive.

Joel, Wagner’s libretto is in faux-archaic German — it’s in alliterative verse, for example, and he always calls a horse Ross, “steed,” rather than Pferd, the usual word for a horse — but the translation was also made at a time when most second- and third-rate poets in English thought archaic diction sounded better. Thus it’s kind of both.

David BTL, Castiglione called that sprezzatura, and considered it to be the supreme grace that a gentleman can achieve. How do you get there? Well, Castiglione might be a good start…

Anna Russell, a marvelous operatic comedienne, has summarized the Ring Cycle for the edification of the “average opera goer.”