In the last post in this sequence, two weeks ago, we watched Alberich steal the magic gold from the bottom of the Rhine. This reenacted in symbolic form the process by which our Western civilization, like every other civilization in recorded history, abandoned the traditional human relationship with nature as a community of persons and started treating it as a passive source of commodities instead. Alberich’s act thus sets the drama of modern history in motion.

This interpretation, as we saw two weeks ago, isn’t something that modern commenters invented. Wagner consciously drew up the scene in those terms. As a passionate believer in the ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach, not to mention up to his eyeballs in the nearly forgotten world of mid-nineteenth century German political and cultural radicalism, he plotted The Rhinegold in the confident expectation that the world of commodification and exploitation Alberich’s deed created was about to crumple before the heroic Siegfrieds of the German radical counterculture. He began writing the music while he was still trying to deal with the way the revolutionaries of 1848 and 1849 had been brushed aside by the forces of the existing order of society. It was only years later, when he was most of the way through the work of composing Siegfried, that he grasped just where the drama of his age was heading, and the revelation nearly broke him.

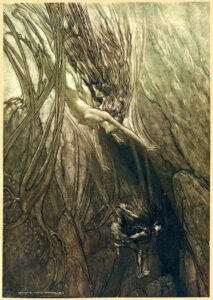

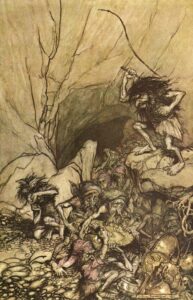

We’re far from that point as Alberich scrambles down from the waters of the Rhine into the subterranean realm of Nibelheim, the world of the Nibelung dwarfs. He’s got the magic gold, he’s forsworn love, and so of course his first action is to hammer the gold into a magic ring—the Nibelung’s Ring of the series title—which gives him power over Nibelheim and its inhabitants. Of course he abuses that power shamelessly; as we’ve seen, when Wagner talks about renouncing love, the word “love” includes every kind of human relationship that’s not mediated by money, so no human (or Nibelung) ties restrain Alberich from doing whatever he wants. The results are just as ugly in this case as they generally are.

(Once again, if you haven’t read the libretto, stop now and read scenes 2-4 of The Rhinegold, which you can download here. None of what follows will make much sense unless you know what’s going on.)

Wagner doesn’t follow him there right away, however. As the first scene of The Rhinegold gives way to the second, the camera of his imagination pans up, not down, leaving behind the world of nature for the world of the gods and giants. There’s Wotan, dreaming about the wonderful castle in the air he’s having the giants build for him, and there’s his wife Fricka, trying to wake him up by reminding him of the price he’s promised the giants: Freia, the goddess of love.

You caught the parallel between the two scenes already, right? Just like Alberich, Wotan’s renounced love in exchange for power. If anything, Wotan’s done it in a more extreme form. Remember that Wagner’s take on the gods was defined by Feuerbach, who interpreted deities as emblems of human ideals. Alberich renounced love (that is, personal relationship with other people and the natural world) in a purely practical sense, driven by his own desperation, but Wotan bargained away the ideal of love in order to pursue his dreams of omnipotence.

Ah, but Wotan doesn’t intend to follow through on his side of the bargain. That’s the thing to keep in mind about Wotan. For all his pretensions of divine glory, he’s basically a slimeball. Alberich, for all his nastiness—and you haven’t seen more than a tiny fraction of that yet—isn’t the villain of The Ring; Wotan is. Yet he’s not a cardboard-cutout villain, one of those dreary figures so common in modern fantasy fiction whose sole purpose for existence is to give the protagonists somebody to despise and destroy. He is The Ring’s villain but also its tragic hero, the character whose actions set the plot in motion and drive it step by step, despite all his best and worst intentions, to its apocalyptic end.

(He’s also Richard Wagner, by the way. The Seattle Opera production a few decades back that dressed Wotan as Wagner and the rest of the cast as opera singers and backstage personnel, and made the sets represent a German opera house of Wagner’s day, was engaged in the sort of postmodern posturing all too common in modern opera, granted, but this once, that usually silly habit actually had a point. Look at Wagner’s life and writings up to the point at which he started writing the music of The Ring, and the parallels are impossible to miss. Like Wotan, Wagner built a castle in the air, engaged in dubious activities to try to make it a reality, and had it all come crashing down in flames around him. Unlike Wotan’s story, though, Wagner’s didn’t end there.)

To grasp what Wagner intended to say—as distinct from the self-portrait that got into The Ring the way it usually slips into every writer’s major works—it’s here again crucial to remember Ludwig Feuerbach’s insistence that the gods are human ideals, symbolic representatives of the vision of human possibility central to each culture. Wotan, the king of the gods in Wagner’s version of Norse mythology, fills this role for modern Western civilization. He is its image, its ideal, its archetype, observed with a keen and unsympathetic eye. “Take a good look at him!” Wagner wrote of Wotan in a letter to a friend. “He resembles us to a hair; he is the sum of the intellect of the present.” To the extent that each of us participates in modern intellectual culture, dear reader, you are Wotan, and so am I.

Let’s watch him at his antics, then, and see how clear a mirror he holds up to ourselves and our society. Wotan’s renunciation of the organic order of things begins well before he cut a deal with the giants that he never intended to keep. His first act, long before the orchestra starts up, was breaking a long straight branch off the World-Ash-Tree—that’s one word in German, in case you were wondering—and using it as raw material for his magic spear, on which the contracts that undergird his power are carved in runic letters. As we’ll learn in the prologue to The Twilight of the Gods, the World-Ash-Tree never recovered from the wound. It sickened and died, and the magic spring over which it once grew ran dry.

Next came the deal with the giants, which as noted already he never intended to keep. His plan was simply to have Loge, the fire-god of reason and logic, find some wiggle room in the contract so that Wotan didn’t have to hand over Freia to the giants. Now, though, the giants have finished their work. Valhalla, the castle in the air Wotan planned, is finished—there it is on the backdrop of the scenery, with a rainbow bridge leading to it. Now the giants want their wages. Fricka, Wotan’s wife, upbraids him—she spends a lot of time doing that—for cutting such a bad bargain.

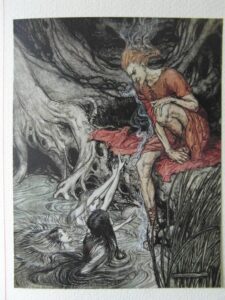

Freia, the goddess of love and eternal youth, comes running in a panic, because she doesn’t want to go with the giants. The two giants, the brothers Fafner and Fasolt, show up, demand that she be handed over, and remind Wotan that his power depends entirely on the contracts carved on his spear, including the one that binds him to pay for his castle. Two more gods, Donner and Froh, turn up to squabble with the giants. It’s quite the quarrel, and more than once threatens to break into open violence.

Finally Loge shows up. Wotan demands that he untangle the whole mess. Wagner knew how to write a trickster god; Loge teases, temporizes, evades and delays; he explains that he wandered all over the world, looking for something that would be more desirable than love. Everyone he met agreed that love is the best thing ever. Except, says Loge, there’s this Nibelung dwarf who renounced love to win the gold from the bottom of the Rhine, and now he’s made it into a magic ring and used it to become fantastically wealthy and powerful.

Alberich thinks this is better than love, Loge goes on, but of course you, Wotan, won’t see things that way—in fact, the Rhinemaidens asked me to tell you about this so you can get their gold back for them. He has a lot of the same sort to say about the gold. By the time Loge’s finished with his description, the giants and gods are drooling over the thought of getting Alberich’s wealth—well, except for Wotan, who is more ambitious than the rest of them. Power matters to him more than wealth, and so he wants the Ring and he wants it bad.

That is to say, every one of them makes the same choice Alberich did, with less motivation.

Loge then slyly points out that it would be easy enough to steal the gold from Alberich. That’s as much as the giants need to hear. They state their terms: if Wotan gets the gold from Alberich, they’ll accept that in payment in exchange for Freia—and they take her as hostage to force Wotan to keep his promise. Lacking her, the gods lose their strength and glory, and so Wotan and Loge go scrambling down to Nibelheim to get the gold. In the process, they see the brutal factory existence to which Alberich has consigned his fellow Nibelungs.

Loge tricks Alberich into showing his magic power by turning into various critters. Once he turns himself into a toad, Wotan grabs him, and the two gods go hurrying back up to their own realm with their captive. Wotan demands all his treasure as ransom for his release. Alberich grudgingly consents, and up come the Nibelungs carrying heaps of treasure. Then Wotan demands the Ring. That’s where we get to see the difference between Alberich and Wotan, and the comparison is not in Wotan’s favor. Alberich knows the price he’s paid for the Ring; he cuts through Wotan’s dishonest moralizing rhetoric in a furious outburst, accusing Wotan of wanting to take the gold all along but being too much of a coward to pay the price; and he warns Wotan that it’s one thing for a Nibelung to renounce love but a far more terrible thing for a god to do the same thing.

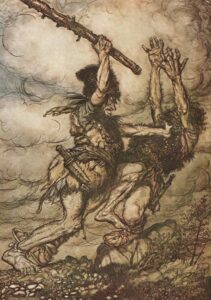

Wotan doesn’t care. He wrenches the Ring by force from Alberich’s hand and puts it on, then tells Loge to set Alberich free. Once freed, Alberich pronounces a terrible curse on the Ring: it will bring misery, dread, and death to anyone who wears it. Then he stumbles back down to Nibelheim, leaving Wotan to gloat over his magic ring.

Next the giants come back. They gather up all the gold—but then they want the Ring, too. It takes the combined efforts of all the gods, as well as a sudden appearance of Erda the earth goddess, to convince Wotan to hand it over. Of course Alberich’s curse takes effect immediately; Smeagol and Deagol—excuse me, Fafner and Fasolt—quarrel over the Ring at once. Fafner kills Fasolt right there in front of the gods and everyone, and he takes the treasure and the Ring and leaves the scene. Wotan, shaken by the sudden eruption of the curse, still manages to convince himself that he can regain the Ring and avoid the consequences. He and the other gods cross the rainbow bridge into their new castle. Loge, in an aside to the audience, shakes his head and comments that the gods are going straight to their doom. Meanwhile, far below, the Rhinemaidens mourn their lost gold. Theirs are the last voices heard before the opera ends.

It’s easy enough to translate all this out of the florid imagery of mythology into the Feuerbachian terms Wagner had in mind while he was writing it. We discussed two weeks ago how love, in Wagner’s symbolism, stands in for the whole range of personal relationships that unite human beings to one another, to their communities, and to nature: the foundation, as we’ve seen, of human social and ecological existence in the early stages of every civilization and the baseline to which the survivors return when every civilization falls. What Wagner wants to discuss in the language of mythological opera is how the Western world abandoned that foundation.

The fascinating thing, at least to me, is that he got the history right. Remember, here again, that Wotan and the gods represent the ideas and ideals of society, and in another sense the intellectual and celebrity classes. Wotan in particular is the Western intellectual mainstream, “the sum of the intellect of the present” in Wagner’s own phrase, and it’s a matter of straightforward historical fact that the foundations for the modern industrial world were laid centuries in advance by the thinkers of the Western world, who spent most of a millennium making the commodification of the world thinkable.

As Lynn White pointed out many years ago in a crucial essay, “The Origins Of Our Ecological Crisis,” that process began with the rise of Christianity. That’s not to say that Christianity did it all by itself—quite the contrary—but by denouncing the old gods and spirits of nature as evil and reimagining the world as an artifact rather than a natural growth, the Christian churches laid a foundation on which later materialists would build. The nominalists, whom I discussed in an earlier essay, took things a step further to reducing the mental realm to a collection of arbitrary labels; from there, with the resurgence of philosophy in the wake of Descartes, all the necessary ideological framework for the desecration and commodification of nature fell into place.

Alberich’s terrible deed, as I suggested, was driven by the hard political and ecological realities of European life during the Little Ice Age, but Wotan broke off his branch of the World-Ash-Tree long before. What’s more, ambitious god that he was, he’d already pawned the goddess (that is, the ideal) of love and beauty in order to get his castle in the air built to his satisfaction.

Wagner made that whole transaction as edgy as he did, I suspect, because it was a bargain he’d made himself. Every intellectual and every creative talent who seeks respectability and a comfortable place in society makes some version of that deal. The people who control power and wealth—the giants, in the myth; the aristocratic class, in Wagner’s day; the managerial class, in our time—are rarely intellectual or cultured themselves; their mental capacities, which range from the mediocre to the considerable, have to be applied to the challenging art of maintaining and increasing their own wealth and influence, leaving little time for anything else. To them, the labors of intellectuals and creative talents are useful tools in the struggle for power and prestige, and intellectuals and creative talents have to recognize this and craft their creations accordingly if they want to get the respectability and the resources so many of them crave.

There’s an alternative, of course, for some intellectuals and some creative talents. You may be able to write books and articles for fringe communities, and get by that way. You may be able to paint or draw, so long as you don’t mind selling your work for postcard prices, and you can probably play music at the local honky-tonk and make some money. You can’t compose grand opera that way, though. Wagner had to sell himself to the rich and powerful if he wanted to follow his artistic vision. Given his pride, that must have twisted in him like a knife.

But there’s a further dimension to the bargain with the giants. The intellectuals and creative talents of every society create visions of what that society could be. In our society, with its fixation on progress, those are visions of the future; in societies with different relationships to time, the visions focus on the glorified past or on an idealized form of the present instead. The visions that matter aren’t created in a coldly manipulative spirit; they’re heartfelt, and express collective longings, which is why they’re embraced so fervently by so many people. Cutting a bargain with the giants in order to build your personal vision, your palace in the air—that’s a tempting deal for any visionary. Many people fall for it, and most of them go far out of their way not to notice how much of the vision has to be bargained away in order to get some of it in place.

That’s woven into the history of every civilization, but it takes a distinctive form in each case. In ours, the first stirrings of industrialism tossed a wild card into the middle of play. All of a sudden the gods and giants had to deal with the rise of a new power, the first sketch of a capitalist class, which could cash in the explosive expansion of wealth made possible by deepwater shipping and the earliest forms of mass production for the more intoxicating coin of power. Obviously it was essential to existing holders of power to take that magic ring from its makers.

Just as in the opera, they did it partly by force, and partly by embracing the same renunciation of love that got the Ring for Alberich in the first place. That is to say, they used their control of European political systems to keep the industrialists in line, and embraced the commodification of nature in order to give themselves ample wealth to take a dominant position in the rising capitalist system. All across Europe, kings and aristocrats converted feudal relationships based on personal loyalties to financial relationships in which only money mattered.

Much of that conversion was done with impressive brutality. Most of my paternal ancestors came to the New World because of one example, the Highland clearances—the mass deportation of most of the population of the Scottish Highlands. People whose ancestors had lived on the same land for centuries beyond counting were driven off their land by their own clan chieftains, their houses burnt and all their traditional rights taken from them, so that the lairds could lease out the land for sheep raising to feed Lowland mills with wool.

If you want to know why so many people of Scottish Highland descent these days live practically everywhere in the world but Scotland, and why most of their ancestors dropped their language and culture like a hot rock as they fled all over the globe, now you know; those who have been betrayed by the clan leaders they were taught to trust, admire and support routinely do such things. Similar scenes were enacted in quite a few European countries, for that matter. The mass migrations of impoverished European farmers all over the world had causes that don’t always get into recent history books.

Notice, finally, Wotan’s response to all this. Despite everything that happened, despite Alberich’s curse and the warnings of Erda, he still wants the Ring, and the power and wealth that it provides. That’s true of most mainstream intellectuals. In Wagner’s time it was even more true than usual, since the role of the philosophes in launching the French Revolution convinced a great many intellectuals that they ought to do the same thing, plan out a wonderful new world, and then get other people to make it happen. That’s exactly what Wotan has in mind. He plans on getting somebody else to get the Ring for him. That strategy didn’t work out too well for the philosophes, all things considered, and it worked even less well for their heirs in 1848 and 1849. In the operas to come, we’ll see how it works out for Wotan.

Reading through the opera itself and your blog posts on it, it boggles me that Tolkien denied any similarity between Wagner’s opera cycle and his own Ring story even while he ripped off huge chunks of it wholesale. Do you think there was a deeper reason for this, or was Tolkien just being his often-curmudgeonly self?

One thing I noticed as I looked more deeply into history a few years ago is that mass migrations from country to city fairly frequently weren’t just caused by pull factors like more jobs in the cities and people going to seek their fortune. There were MANY clearances of various kinds, and in recent times mechanization of farming and reduced need for labor and inability of many small farms to compete with large, subsidized and very mechanized farms has had a very similar effect in the emptying out of the countryside worldwide.

People often/usually weren’t jumping of their own free will, or not their own will alone; they were being pushed.

Most history book really like to downplay the role of elites and governments in actively dispossessing their own citizens and forcing them off the land – at least, unless they’re talking about european-ancestry groups dispossessing indigenous groups. For the rest, you find bits and pieces that you have to put together yourself, and the picture that emerges is pretty disturbing. The people pushed off the land go to the city, where they become cheap labor that fuels the industrial revolution in that nation. Labor whose alternate choice was taken from them, and can now be exploited to horrific levels. Happens everywhere from Ireland to the USA to China to Bangladesh to Scotland.

People argue that the factories were obviously better than the farms because people chose the factories. But if you have no access to land or work in the country because it was actively stolen from you, this is not a valid argument.

Cities tend to be population sinks rather than population sources, and I suspect the huge and increasing proportion of the world’s population now living in cities is one of the more important reasons that birth rates are now dropping so fast.

I hope everyone here has a good day!

I must say that I am not content with the blame that is put on Christianity. Christian principles are the opposite of the desire to reave nature of it’s bounty. I bring up the instructions that God gave to Israel regarding the land and it’s preservation, how Israel was indicted for exhausting the land. Remember Paul as well, in chapter 8 of his letter to the Romans he says that creation is groaning because it is in bondage under our bad management and that God prepared hope of it’s release.

Remember Jesus talking about our anxieties in how we procure our food and clothing, that it is wrong to maddingly pursuit these at the cost of love, for it is Love itself, the Father’s love, that sustains us.

I see that you pointed out “the Christian churches”. A subtlety with which I agree, for love of others and love for creation is built in the definition of Christianity, but organizational Christianity is always tainted by human shortcomings, but never completely for the head of the Church is a pristine and incorruptible High Priest who always takes back His Church from the clutches of human failure never allowing it to be “conquered by the gates of Hades”.

Thus far I’m very much enjoying the saga!

A parenthesis…you said, “…by denouncing the old gods and spirits of nature as evil and reimagining the world as an artifact rather than a natural growth, the Christian churches laid a foundation on which later materialists would build.” I expected, and first saw, “by denouncing the old gods and spirits of nature as evil and reimagining the world as an artifact rather than a natural growth, the Christian churches laid a foundation on which materialists would later build.” Are you saying that Christians were/are at least proto-materialists (because they see the world as a made object)?

(This is off topic for today and not intended as a ‘comment’)

Dear Mr. Greer,

In light of the upcoming 5th Wednesday on the topic of Hitler, I wonder if you’ve read Blitzed by Norman Ohler? It is an examination of drug use in the Third Reich. I was shocked that I’d never heard the topic mentioned in history books but it does help make sense of some of the crazier notions that came out of Munich. https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/29429893-blitzed

It’s interesting that oxycodone and methamphetamine use/abuse was prevalent in Germany and much more recently in portions of the United States. Could there be some link between those particular drugs and the ideologies of both places?

Meth does initially induce a “Superman” type of feeling; pain, fatigue and doubt all fall away. Like most drug abuse, it tends to not end well for the users of course! But if you are trying to create an army of disposable super-soldiers, Pervitin pills make a certain kind of demented sense and of course, they didn’t really grasp all the downsides until it was too late. https://www.amusingplanet.com/2020/05/pervitin-wonder-drug-that-fueled-nazi.html

I look forward to your post on the man, the myth and the archetype,

Sincerely,

Ken

JMG,

This series is awesome. I didn’t expect it to cut QUITE so close to home… As a young musician about a decade ago, I made my own pseudo-faustian creative bargain with those in power and wealth… The consequences would have been obvious, if I had been paying attention.

Noodles

As far as I can understand, the only way to find harmony is by abandoning industrial civilization. I mean on a personal level, I wonder if there are places and groups of people who rehabilitate other people who spent a lot of time in modern civilization. I am interested in these places and groups of people.

Japan had the same immigration dynamic as Scotland in the 1800’s. As the Meji restoration took hold in the 1880’s all the old feudal relationships were abolished and many traditional Japanese farmers were turned off their land. That is when my wifes grandfather came to Japan.

The interesting thing is that if you read conventional history sources. they like to ignore this and give other reasons for large out-migration from Japan, Scotland and other places. For instance Wikipedia ( cough cough) says the cause of out migration in Japan was war with China and and an economic downturn. Which seems like stupid reasons.

Even today the narrative is maintained that feudalism is bad, and monetary industrial servitude is good. So it can’t possibly be that people would want to leave when feudalism ended and the great new era of working in a mill for pennies came.

Thank you for this enlightening work.

Ken : drugs were and are used for all the military in all the countries.

One bizarre history is the history of the soldier Aimo Allan Koivunen

While fleeing a Soviet ambush, Koivunen took a near-lethal overdose of methamphetamine. The drugs helped Koivunen cover hundreds of miles of ground – but they nearly killed him in the process.

Full history

https://allthatsinteresting.com/aimo-koivunen

So Wotan gets the Ring before he has to give it to the giants. Is this Wagner’s nod to the revolutionaries, who seized power from the capitalists for a moment before being forced to give it back to the aristocrats?

I guess one of the things you are saying here is that Wagner pursued the 20%

[See Greer’s Law: https://ecosophia.dreamwidth.org/299920.html?thread=51613840#cmt51613840 ]

James, partly it was Tolkien being the grumpy old git that he became in his later years, but there was another factor. Tolkien was a rock-ribbed religious and political conservative, and he bristled at the way that people on the opposite end of the spectrum — especially Wagner and William Morris — had reworked the old Germanic legends to fit their beliefs. The Lord of the Rings is in large part a counterblast to Wagner’s operas and Morris’s fantasy novels, and includes quite a few elements that more or less parody both — for example, the chief villain in Morris’s greatest fantasy novel, The Well at the World’s End, is named Gandolf…

Pygmycory, yep. Our current elites love to talk about what their precessors did to the indigenous peoples of the rest of the world but they really, truly don’t like to talk about what the same predecessors did to the indigenous peoples of Europe.

Rafael, if you go back and reread my comments you’ll find that you’ve completely missed the point that I made.

Roldy, no, I neither said nor implied that. It’s rather dispiriting to watch the point I tried to make being ignored so that a familar polemic quarrel can be trotted out.

Ken, I have indeed. For what it’s worth, I think our current elite uses cocaine more often than meth.

Noodles, the only thing that saved me from making the same bargain was the slowness of my learning curve as a writer. If I’d broken into print in my 20s I’d probably have gotten sucked into the trap of writing for the big corporate publishers, and had my own voice and vision stifled.

Zarcayce, nope. That’s been tried over and over again, and it doesn’t work, because try as you like, you’ll take the mental world of industrial society with you. (It’s another case of “wherever you go, there you are.”) No, the only way out is through.

Clay, that’s another fine example. As the Meiji regime tightened its control over Japan, it adopted most of the bad habits of the European regimes it copied, and that was one of them.

Randal, you’re welcome.

Roldy, very likely that was part of it. I suspect it was also a nod to the Renaissance, however.

Justin, since he wanted to be an opera composer, he locked himself into that choice.

Sorry, no polemic implied – I just wanted to be clear that when you compared “Christian churches” to “later materialists” it was just inadvertent phrasing. Thanks.

@JMG, I’m actually not just talking about the past. I’m also talking about policies today in China, and the situation in Bangladesh (though that’s partly sea level rise/salt water intrusion mediated). Also in Africa, with corporate takeovers of tribal lands mediated by government. It hasn’t actually stopped.

It’s interesting that by giving up the Ring, Wotan gets Freia back, so has at least the option of renouncing power and returning to love. Alas, ’twas not to be.

Wotan reminds me of Faust, who probably didn’t give much thought to the price he’d have to pay when he signed the contract (or thought he could find a way to wiggle out of it).

Ha. I published a very similar essay today, except it was the trashy dime store version with horror movies, psyops, and Islamic terrorism. Your way of thinking feels more and more like a lifeboat now that all the abstractions are sinking into the abyss.

https://naakua.substack.com/p/second-religiosity-the-final-chapter

From the bible this is what you give up when you renounce love

“Love is patient,

love is kind.

It does not envy,

it does not boast,

it is not proud.

It does not dishonor others,

it is not self-seeking,

it is not easily angered,

it keeps no record of wrongs.

Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth.

It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres.”

and a depressingly accurate description of what Industrial Civilization is not.

The greeks had several different words for love

Eros: Romantic love

Philia: Deep friendship or brotherly love

Storge: Familial love

Agape: Divine love

Philautia: Love of the self

Ludus: Playful love

Pragma: Long-standing love

Did you need to renounce them all to get the ring?

My sense of what you just described? Alberich is the only character in that whole miserable story that actually wanted to work. And actually got something done. You can argue over whether it was foolish or not, meh. The sorry lot of them wanted to leech off someone else. Some gods.

Although that does make me wonder. Why would a god that has plenty of power to begin with, want more power?

And the World Tree – so that’s where Blizzard ripped that off from.

Re: Pygmycory (#2), JMG’s answer to that (#13)

This is a point I realized a few years ago when I read Simone Weil’s ‘L’enracinement’ (the English translation is called ‘The Need for Roots’). This is a strange book, a political manifesto she wrote during WWII, which, like so many other books of this genre, is very perceptive in its diagnoses and very unrealistic in its practical suggestions. The central claim is that one of the most basic human needs is having roots, that is, belonging – to a land, a culture, a community. Faustian civilization has been engaged, since its inception, in uprooting. During colonialism it uprooted countless cultures around the world. But this could only work because it had uprooted itself first, or rather its ruling classes had uprooted the peasant population.

Weil doesn’t speak about the enclosures in Britain but about similar processes in France. Before France could subdue and homogenize the banks of the St. Lawrence, the Maghreb and Vietnam, the rulers of the Île de France had to subdue and homogenize the Languedoc, Brittany and the Périgord.

Of course the usual polarization in politics makes this connection invisible. If Brexiteers and Indigenous Amazonians realize they are up against the same enemy, some interesting things might happen.

Dear JMG,

Following the answer to Zarcayce, would you be able to clarify “the only way out is through [the industrial civilization]” ? Does it mean enduring it ?

Kind regards

Zarcayce #7

> I am interested in these places and groups of people.

I would opine that such places and people would include:

(1) Existing farm communities.

(2) Farmers, farm families, and their extended families.

💨Northwind Grandma💨🐖🐑🧑🏽🌾🌱🚜

Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

I can understand why. He obviously had the talent and the will to see his project through, and it obviously has had a far reaching effect. Just ask smeagol!

Fantastic essay. Thank you for all tbe parts about the choices creatives and intellectuals make and face. A lot to chew on there.

Good essay JMG

As for “Even today the narrative is maintained that feudalism is bad, and monetary industrial servitude is good.”

Feudalism and Monarchy have a common problem (in both senses of the word.) What if your lord or sovereign is a bad ruler? What’s your recourse? Oh, there isn’t one except to try to escape. Voting the bums out might not work, but it’s safer to try that than armed revolution.

Even though Feudalism and Monarchy should encourage long term thinking since the grandkids will inherit all too often the grandkids turn out to be entitled snots only interested in hedonism. Then it all falls apart.

A great continuation of the series! I understand better now that the gods here represent both ideas and creators of ideas, not just any kind of middle class. Thanks also for your subtle appraisement of the role of Christianity in the desacralization of Nature: “that’s not to say that Christianity did it all by itself—quite the contrary”. A not too different take can be found in Charles Taylor’s A Secular World, which hasn’t stopped Taylor being a devout Christian.

When you write about the “earliest forms of mass production”, are you thinking also of tropical sugar and tobacco monocultures worked by indentured European servants and African and indigenous slaves? Graeber’s Debt cited a rather obscure French reference to the effect that the discipline and regulation applied to “free” workers in the factories of the Industrial Revolution was pioneered in the tropical plantations with unfree labor. I have never read that French reference, but the connection seems plausible. Another example of how unsavoury measures applied abroad finally come home to roost.

The example of the Scottish clearances is heartrending in part because it is well-documented, having taken place in a country with mass printing. Countless similar episodes of treason by former clan chiefs have probably taken place over the millennia, from the founding of dynastic Egypt (told very well by David Wengrow) to Hawai’i, though the disenfranchised were usually retained and not put to flight.

I think the elite attitude to uppers is along these lines:

Cocaine is a clean drug fit for the wealthy and well to do jet setters. If it worked for Freud and Doyle it can work for us!

Meth is a dirty drug fit only for trailer trash and ghetto fiends, or crazy scifi writers like Philip K. Dick. Don’t point the pink beam at us! Plus ut rots out your teeth and Daddy wont pay for another set of full implants.

I witnessed that Odin bargain when finishing my art undergrad, when I realized that the fine art world was actually just a way to make a meager living off of rich people’s money laundering and tax avoidance schemes, with no relationship to the product produced. I didn’t make the bargain, but then again I realized at the same time that I am not nearly talented enough to succeed in that industry anyway (at least without resorting to unethical tactics), so it wasn’t a real option anyway.

You skipped over Alberich’s plan to enslave the world and overthrow the gods with his wealth and his ring! I thought it was interesting how Alberich, with all his newfound power and freedom, has no better plan than revenge against creation for his misery.

Hi John Michael,

Well, yeah, treat any relationship like an object, and things are inevitably going to end badly. It’s not lost on me that the cursed bloke treated his debtors with disdain, much like Wotan would have approved of. The parallels are strong. Interestingly I tried that trick too as a very young bloke, and got thumped for my efforts and also coughed up the mad cash, and that was a good lesson to take relationships seriously.

I must say, it amuses greatly to see debts worldwide spiralling ever upwards into the dark realms of the non-relationships. The end point will of course be the same, a good solid thumping. The difference here is, I was a child, but then an argument could be made… 😉 As far as I can comprehend the situation, it’s the same, but on a huger scale, and I doubt that there is an intention to pay, so the thumping is foreordained.

Yup, the clearances. And so my lot turned up down here and repeated the act on the locals. Hmm. A curse, upon a curse, upon a curse. Not good. And the payments are building.

Dude, I saw how the winds were blowing, and chucked my lot in with nature. But even so, a dudes gotta walk in two worlds all at once.

Good to hear that the worst of the weather missed you. That mostly happens here as well. Some places are like that aren’t they?

Hi RandomActsofKarma,

Thanks so much for the explanation last week, and you’ve given me plenty to think about.

Cheers

Chris

Roldy, I was contrasting them with materialists before Christianity, of whom there was of course no shortage.

Pygmycory, that’s a valid point.

Roldy, the comparison with Faust is a valid one — the two figures have a very great deal in common.

KVD, thanks for this! Having grown up on trashy dime store fantasy stories, I still have a soft spot for that end of literature; I’ve bookmarked your essay.

Dobbs, it’s not necessary to be a Christian to recognize that there’s a lot of wisdom in the Bible. As for your question, as I mentioned, you have to renounce all human relationships and replace them with strictly economic relationships, so yes, it’s the lot.

Other Owen, how many intellectuals do you know? An aversion to hard work is not exactly rare in those circles…

Foxhands, what I mean is that there’s no way to run away from it, since you take its modes of consciousness with you. You have to deal with the industrial civilization in yourself, and you have to do it here and now, not in some imaginary refuge — keep in mind that the vast majority of people who dream of fleeing someplace to get away from industrial civilization will never actually do anything of the kind. That’s what I’m trying to teach people how to do.

Justin, you’re most welcome.

Siliconguy, what if all the choices your supposedly democratic system presents for your vote, in election after election, are sleazebags who are pushing the same policies? In a hereditary system you at least have the chance now and again at a good king.

Aldarion, the role of plantation slavery as a forerunner of factory labor hadn’t occurred to me, but it’s quite a plausible suggestion and deserves further exploration.

Justin, that’s the impression I’ve gotten, certainly.

John B, that’s a good point. Alberich’s like so many people raised in an oppressive background; the only alternative they can think of to being oppressed is doing the oppressing. It takes an unusual kind of insight to imagine something else.

Chris, yeah, I think a world-class thumping is on its way.

“If Brexiteers and Indigenous Amazonians realize they are up against the same enemy, some interesting things might happen.”

Robert, it is the purpose of the “diversity” scam to make sure they do not realize.

Not sure how on topic this is but it sort of fits with some of the comments, I think.

Christians say that we are made in God’s image. This is something I believe and it informs the way I treat other people.

However, perhaps what we really do is make God in our own image. So much more comfortable and easier to understand him.

Hi Archdruid John,

What are you thoughts on the real Wotan/Odin? How different is he from the opera treatment he gets from Wagner?

Just as as a PS: The French book David Graeber cites for the claim that capitalism started with, and has always continued to be built on, mostly unfree labor is Yann Moulier-Boutang, De l’esclavage au salariat: Economie historique du salariat bridé. It’s funny because after reading Debt, I asked Graeber for a different, non-French source, and he couldn’t give me any. Nowadays, I would be able to read it in French, though the book doesn’t look easy to find or to read!

@Other Owen: The giants laboured quite hard to build Wotan’s castle, and they make a point of comparing their hard work with this sleep! I find that quite out of character for aristocrats.

I must say I have difficulties reconciling Wagner’s off-stage characterization of Wotan as “the sum of our intellect” with his on-stage performance. He doesn’t seem intellectual at all but depends entirely on Loge for suggestions and solutions. He reminds of nothing so much as of mediatic politicians like Macron, Pena Nieto or Justin Trudeau.

JillN, as I see it, we can’t understand the Divine — the finite cannot comprehend the infinite — and so we necessarily (re)make our gods in our own image.

Felix, as far as I can tell they have nothing in common but the name.

Aldarion, I read French fluently, so if I can find a copy I’ll have a look at it. As for “the sum of our intellect,” well, what does that say about Wagner’s opinion of the intelligence of the modern Western mind?

@JMG,

Once again, your Wagner essays are a real pleasure to read. I don’t think that anyone else I follow on the internet has even half as wide a range of interests as you do!

I wonder sometimes if Wagner’s story would have caught so many people’s imaginations if it had to stand on its own, apart from the music. Suppose he had just been a novelist, or a playwright – would anyone remember his eccentric take on Norse mythology? Yet with a musical talent like his I figure that any tale could go a long way….

I will admit to disliking the mostly-negative l light in which Wagner portrays Wotan and the other Gods. I always had the impression that in the original myths they were usually heroic figures, who created mankind and who fight hard to keep Loki and the giants at bay, even as they know that sooner or later they’ll perish in Ragnorok. They may not be all-knowing or all-powerful like the Christian God, but they’re more benevolent than Wagner gives them credit for. (Some Christians might argue that with epithets like “Glutter of Crows,” Wotan is also too violent to be compared to their God, but I don’t think this is fair. Jehovah is deep into the crow-glutting business too. See Jeremiah 16:3-4, Ezekiel 39:17-20, and especially Revelation 19:17-21. Or just look up the phrase “Supper of the Great God.”)

It seems to me that Tolkien had similar feelings, which might explain why he disliked the Ring operas and pretended not to be influenced by them. After all, in Tolkien’s cosmos, the Valar fight hard to bind the Loki-like figure of Melkor/Morgoth, and Gandalf looks a lot like Wotan as “the Wanderer,” and Manwë has ravens bringing him news from all over the world, and the high God over all of it is Eru, called “Iluvatar” by the Elves. (Iluvatar being Quenya for “All-Father,” a major title for Wotan which never shows up in Wagner’s works.)

But if Wagner, as a Feuerbachian, is just using the traditional gods of the Germanic race as a mirror for (what he sees as) that race’s most powerful and influential figures… perhaps also influenced by Greek mythology, which is made mostly of stories about powerful but short-sighted and selfish gods using vulnerable human beings as pawns in their games… then I figure it works. The character development through the four operas is solid, as is the tragic ending for Siegfriend and Brünhilde, and of course the music is wonderful.

Thank you for these explanations of the Ring Cycle, JMG. I honestly did not understand it or its appeal until now even though I studied music in college. For those who have not been following mainstream news, there is a famous entertainment producer named Sean Combs a.k.a. Diddy who was arrested and thrown in jail. We are now finding out he was into nasty stuff. He is an Epstein-like figure who spent most of his time obtaining compromising videos of celebrities and celeb-wannabes. He seems to me like a modern Alderich, enslaving and assaulting everyone and everything around him, obsessed with wealth and world domination. Combs was a significant domino. His fall is taking a large swath of cultural visions and ideals down with it, but in many ways, those visions and ideals were cursed to begin with. I’m planning to address him in my next weekly essay.

Thanks Archdruid John,

Great to know he is nothing like the opera version. What is the real Wotan/Odin like? Is he a deified Norse/Gothic hero from long ago? Or is he an arch type? I see that most of the gods represent some kind of order over chaos.

How do I get into contact with him? How responsive is he?

Thanks

Felix

From the last discussion on the Rhinegold I got totally swooped about Wotan being not an external idea, or an idea of part of our cultural ecosystem like justice/lawgiver and artist/beauty, social custom, love and relationships, logic and reason. But the idea of self and intelectual self. The identity.

So in the scene where every internal faculty of modern culture is begging the self to yield the craving for power, where the very Earth deigns to speak against it. Wotan yields in deed but not in mind.

What still puzzles me is who Edda is, “Goddess of the Earth”, but I suppose the answer this week is the same as two weeks ago; the answer will be forthcoming in the Valkyrie and the Twilight of the gods. 🙂

@Other Owen: @Aldarion: Seems to me that the work the giants are referring to is the same as described by John n this essay;

“the aristocratic class, in Wagner’s day; the managerial class, in our time—are rarely intellectual or cultured themselves; their mental capacities, which range from the mediocre to the considerable, have to be applied to the challenging art of maintaining and increasing their own wealth and influence”

If you ever met some of the managers/accountants/entrepreneurs, they work all the time. They are constantly on call. They do not have the time to dream about “the better world”, they have to keep their department in line, on schedule and on budget. Plus their superiors happy. They got no time to dream. 70 hour workweek is the norm.

@Mary (#30)

It truly is!

Hi John Michael,

Whilst reading through the comments a little thought popped into my head: Loge would make a good economist don’t you reckon?

Cheers

Chris

Yeah, if giants = nobility, then their hard (or rather, dangerous ?) work would be better shown by results of conquest… but then of course that wouldn’t fit with the rest of story – if Wagner was so prolific, he must have said something about this choice ?

@John B, well, Alberich *did* renounce all love !

(BTW, thanks @dobbs for reminding us of the yet very different conceptions that Ancient Greeks had of “love” – which lived in a society both very different than medieval Europe (politics, slavery), but also very similar (agricultural society).)

I’m afraid that one issue with this blogpost might be the use of “feudalism” as a valid concept. Historians seem to have never been particularly happy with it, and in fact obsoleted it half a century ago : “The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe” AHR 79.4 (1974)

The creation of that concept seems to be the result of on one hand a myopic focus on Europe’s Middle Ages, and on another hand the main sources for a long time being the written texts : paid for by and therefore written almost exclusively for nobles (and especially the highest rank nobles) and the Church.

The others –

not sure if Third Estate would be too much of an anachronism to use here, since it was seemingly pushed so much by the bourgeois (=city-dwellers), which, as a reminder, did exist even in Medieval Europe, but were perhaps even more separated from peasants than in Wagner’s modern era (before the printing press and the start of alphabetization) –

the others are basically invisible in the written texts, and it’s the progress in archeology, especially over the last decades, that now allows us to have some idea about their lives.

Anyway, “feudalism” might be better understood as when circumstances make vassalage meet manorialism/serfdom.

Vassalage being the social system where there is basically no state capacity, so it’s all based on personal relationships between elites, which are a warrior class : the experience of war bringing them even closer together

(also remember that the poor medieval peasant made for a paltry fighter, and specifically, wasn’t a warrior – my guess is that it would be interesting to look at counter-examples, like with English longbowmen, where their hunting skills translated well to warfare).

Vassalage is indeed dead by the beginning of the modern era (mid-1400s), with rising state capacity, (resulting in absolute monarchy rather than vassalage), rising population, and the start of industrial revolution making even peasants (still commanded by nobles) into a much more dangerous force, first with crossbows, then muskets (both being much more expensive to produce, but requiring no lifelong training).

(Also, in Europe itself, it’s only by the middle of the Middle Ages that the system of hereditary land grants against the obligation of military service becomes the norm.)

Serfdom being the (legal) social system where the underclass is neither free, nor in complete slavery – which I guess does involve a kind of love – late modern Russian literature is probably a good place to get a sense for it (or lack of it), since it was only ended in practice by the end of the modern era with WW1 and the Russian Revolution (not that the next system was particularly free either).

BTW, Russia is a counter-example here, since serfdom only became the dominant social system there in the modern era.

Manorialism is an economic system, and a much more prevalent one – it basically seems to be the default for agricultural societies ? (Or is that mostly for plow-based societies ?)

In it, landholders (which are typically rich farmers themselves) exploit the labor of poorer farmers nearby, often taking advantage of the fact that only the rich farmers have any real capital (in the form of (better) tools and beasts of burden).

It was for instance basically the default in most of the Roman world.

(and seems to have suffered a somewhat (but not quite) similar fate in its center as with the Industrial Revolution, except that the energy slaves that replaced peasants in Rome’s neighborhood were literal slaves. They might have gotten a better fate too (at least materially) compared to modern peasants, since once they fled to Rome, the resulting instability resulted in free grain for them to prevent food riots)

Anyway, my point is that the worlds of peasants (farmer class) and of nobles (warrior class) were already very distinct in the Middle Ages (and themselves also very distinct of the few bourgeois free(ish) cities). For instance peasants did *not* pledge fealty to their lord, that was between nobles only.

Not to say that there might have been *some* kind of love / expectations between peasants and nobles… and I would expect that Christianity would actually have had a positive effect here (the Church itself, maybe not so much ?).

Those relatively small love / expectations that would have been ruined by the appeal of mercantile/industrial profit,

which before that pretty much required conquest of new lands,

(long distance trading having become too dangerous during the Middle Ages),

which was only an option for the warrior noble class, and where nobles would have had to face those who they would have considered their peers (and which typically were in practice), not easily walked over lessers.

(The rich non-noble manorial lord peasant, betraying its subjugated same-class peasants feels worse indeed. But, see Alberich’s resentment overpowering everything ?)

I wonder how much this “feodal mistake” comes from the early 20th century generation of historians being too far removed from the old world (completely dead and buried with WW1), and also ironically projecting their expectation of “all men are created free and equal” over the Medieval writings ?

Phew, this came out much longer than I expected, thanks for those that did end up reading it all.

>I must say, it amuses greatly to see debts worldwide spiralling ever upwards into the dark realms of the non-relationships

Amusing isn’t the feeling I get looking at it. Did you know those spiraling debts never could be paid off? That it was baked into the cake from the very beginning? That all the debts are technically bad? That they had to spiral? That they must spiral?

They’ve kept it all going by writing off part of the bad debts and finding ways to reset the ponzi scheme from that lower level. They’d probably be able to do that again, except they’re running into planetary resource limits.

“Foxhands, what I mean is that there’s no way to run away from it, since you take its modes of consciousness with you. You have to deal with the industrial civilization in yourself, and you have to do it here and now, not in some imaginary refuge — keep in mind that the vast majority of people who dream of fleeing someplace to get away from industrial civilization will never actually do anything of the kind. That’s what I’m trying to teach people how to do.”

Thanks JMG, I got the best epiphany from this response. I had come to the realization quite a long time ago that if I tried to move to the country and “go back to the land” that I would just be taking industrial civilization with me. I had not thought to apply that same realization to my intellectual life or my emotional life or even my spiritual life. Live and learn. Now to see if I can apply it to these other areas of my life.

@Aldarion, another French author, Braudel, had quite a different take on the origin of capitalism. He sees its origins in the market economy of the late middle ages in Europe. His work is available in English translation.

A minor bit of synchronicity:

There is this billionaire called Bryan Johnson who is documenting his journey to “not die”. Someone asked him on Twitter:

ahem

@bryan_johnson

would you turn yourself into the worm like in dune god emperor if it would ensure you live an additional 1000 years and become immortal but you had to be a massive worm who was incapable of love?

Yes

I found it amusing, he’s acting out Wotan’s bargain. I feel that the Dune series is like a different take on it though, Leto became a tyrant because he saw that it was the only way to bring humanity to the Golden Path and he went willingly to his death in the end to bring it about.

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Rebecca’s new job position, the start date of which keeps being rescheduled, indeed be hers, and commence as soon as possible; may it fill her and her family’s needs, and may the situation be pleasant and free of strife.

May Divine help be granted to newlywed Merlin (TemporaryReality’s daughter), that she be guided to beneficial information and good decisions that lead to perfect health. May the lump in her breast resolve rapidly with no issues.

May Leonardo Johann from Bremen in Germany, who was

born prematurely two months early, come home safe and sound.

May all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricanes Helene and Milton be blessed, comforted, and healed.

May Kevin, his sister Cynthia, and their elderly mother Dianne have a positive change in their fortunes which allows them to find affordable housing and a better life.

May Tyler’s partner Monika and newborn baby Isabella both be blessed with good health.

May The Dilettante Polymath’s eye heal and vision return quickly and permanantly, and may both his retinas stay attached.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

JMG,

First thank you! This series was thought provoking. Do you think The abandonment of a relationship with nature happens inevitably when there is a resource benefit to extraction at a pace faster than the land provides? If that excess extraction can lead to growth and then conquest of other lands, i can see how extraction can be a temporary “win” causing growth and collapse. To me i see human populations acting like algae blooms. Where resources or technology that allow for extraction cause a bloom and collapse. I am trying to imagine a culture that is both sustainable and stable to invasion. The only species that seem to achieve this consume all the resources like old growth trees, that maintain low soil nutrition, and cover the canopy.

Open to criticism of this train of thought!

Sandwiches, oh, it would have depended on whether he’d have had any other talent on the same scale as his talent for composition. Most operas as written make poor novels and worse poems, but a good novelist or poet could take the same basic ideas and do something amazing with them. As for Wagner’s Feuerbachian reworking of the gods, oh, agreed — and I know a lot of Heathens share Tolkien’s animosity toward Wagner for exactly that reason.

Kimberly, one of the reasons that Wagner’s operas still have plenty of fans is that we all know, or at least know of, exact equivalents of each of the characters. I wonder if we’ll ever find out why, after having been sheltered from prosecution for all these years, Combs/Alberich finally ended up in jail.

Felix, that’s not something I can help you with. You’ll have to go ask some Heathens about that — and, btw, it’s off topic for this comment thread, which is about Wagner’s fictional figures.

Marko, in Wagner’s Germany one of the major intellectual movements was Naturphilosophie, the forerunner of modern ecology, which tried to ground human understanding in the world of nature. I see Erda’s appearance here as a reference to that — the recognition, on the part of a great many German intellectuals, that the commodification of the world was not merely antihuman but in conflict with nature itself.

Chris, in a sense, yes. He was certainly good at telling the gods and giants what they wanted to hear, which is of course the basic requirement for success in economics; his problem is that he couldn’t lie to himself, much less convince himself that the gods hadn’t just doomed themselves.

Peak Singularity, as you see, the line breaks came through just fine. There’s a glitch in the software that makes it look in previews as though they’ve gone away. As for “feudalism,” yes, I know there’s been a lot of fussing about it in the last century or so. I prefer to let the middle ages speak for themselves here — as you may know, there’s plenty of literature from that time talking about the nature of the feudal relationship.

Kay, delighted to hear this. Once you see the current mess as something that exists all through yourself, and not just an outside presence you can flee, you can start to do something meaningful about it.

Alvin, that’s just sad. Really sad.

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Alex, that’s a solid ecological analysis. As for your question, I don’t think human social evolution has reached that successional stage yet!

JMG,

i would agree that human social evolution is not sustainable…. if we look at one of our most sustainable examples i would look at Egypt. however i think they may have existed for so long because the opportunity for extraction was limited. If you think about their farm land, both soil nutrients and water were provided at a constant rate from the Nile annual floods. Excess nutrients were likely washed away and obviously excess water was as well. Because of this the CHANGE of resources was near 0. This is unlike farm lands with rain, as the nutrients taken from the soil are not replaced, so their is either an extraction of the top soil, or a human energy input to maintain it through composting. Since the human energy input is needed to maintain the resource base, a healthy top soil is now a resource that can be extracted from by other peoples who spend their energy taking that land rather than cultivating their own. It also doesnt help the math, that there is a temporary surplus of food when you dont rotate crops. I wonder if Rome insisted on conquered farm land being extracted from rather than cultivated, used the excess to fuel a conquest, and repeated for 1000 or so years of this “growth”

just some thoughts, im convinced that humans behave like algae when you “zoom up” a bit. i wonder if there is any biological system that is sustainable however i cant think of one that would choose not to grow consumption to meet availability of a resource.

@Alvin, This is such a perfect example of a modern version of the ring! the castle in the air is our myth of progress which primarily centers around Ray Kurzweil’s promise of immortality. And when asked he would literally give up Love and every other form of dignity to be an immortal worm.

“However, perhaps what we really do is make God in our own image.”

That would account for the vast gulf between the God of the Old Testament and the one Jesus and John the Baptist were going on about. That brings up the question of what caused people’s self image to change. Did the ravings of the priestly caste finally grow wearisome? Did the priests fail to deliver prosperity while the Romans did?

I just finished reading Michael Lewis’ ” Going Infinite”, about FTX and Sam Bankman Fried.

It is a kind of sideways Wagnerian story in real life. Sam Bankman Fried is a kind of Post-Wotan character who seems to have born without the ability to feel friendship, love or empathy. Almost as if one of Woton’s curses was to father a son bereft of any of those human characteristics.

As Lewis depicts him, Sam was not evil or greedy, just detached from normal human emotions. He then, early in his adult life gloms on to a strange philosophy called ” ethical altrutism” . In a nutshell E.A. says that a human can accomplish the greatest good for the world by making as much money as possible and then giving most of it away to good causes. A kind of “license from the gods”, to make money and spurn human relationships while feeling morally good about yourself.

This of course leads Sam down a path of massive temporary wealth amidst a wreckage of human lives and relationships.

It was not Lewis’s best work, but this post made me realize that it might make the feedstock for a better Opera.

Kimberly Steele, I have not been following the Diddy story. I made a note to myself to read your blog post, I hope you will be able to tell us something about who put him up to it all. Doesn’t excuse him of course, but I take the view that the hit person and whomever purchased the hit are equally guilty.

>Other Owen, how many intellectuals do you know? An aversion to hard work is not exactly rare in those circles

Yeah, Wagner wasn’t really talking about some mythological past, no more than Mike Judge was talking about the year 2505 when he made Idiocracy. For some reason nobody is trying to bury The Ring Cycle though. I guess it’s impenetrable enough on its own.

I guess in some ways Wagner’s operas were the Idiocracy of the 19th c, a scathing critique of the conditions of the time.

@Alvin #46: I hope we are not getting too off-topic here. I see a distinction between mercantile capitalism like the one the East India companies plied, and industrial capitalism. Mercantile dynasties and networks did indeed start to appear in a rather timid fashion from about the 12th century onwards and grew enormously in the 14th and 15th centuries. (Btw, I just re-read some passages where Graeber suggests that the romantic “knight errant” of medieval lays was actually based on the very real “merchant errants”!). However, the East India Companies and others like them did not employ large numbers of people to work in confined spaces. Even into the 19th centuries, a lot of production like spinning and weaving was done by each family in their own home – they received the wool and returned the finished product, but did not go to work in a factory. Since at least some of them owned their houses on their land, they could switch back and forth between agriculture/husbandry and this outsourced work.

What Moulier-Boutang is after (according to Graeber) is that the organization of the workforce into large groups of workers, working in shifts in big buildings under foremen, which we consider typical of industrial capitalism, actually had its origins in tropical plantations that confined and disciplined unfree laborers (indentured servants, slaves or contract workers from other countries like India or China). As far as I know, sugar plantations were pioneered in the 15th century on the Portuguese Açores, saw a huge expansion in the 16th century in the Caribbean and Brazil, and early in the 17th centuries were adopted by the English, too, for sugar in Jamaica and for tobacco in Virginia.

That would have been the training ground for the creation of the industrial working class in Britain itself beginning in the very late 18th century, but first the English and Scottish peasants had to be forced away from the land. They would never have accepted 19th century factory working conditions if they had had any alternative. And that’s where their betrayal by their former clan chiefs or manor lords comes in.

I haven’t yet read Moulier-Boutang myself so can’t judge the evidence. It’s a pity Darkest Yorkshire doesn’t comment here anymore, he would have a lot to contribute!

Are Wagner’s gods Vikings of the Mind? Our managerial class certainly seem to be.

“You have to deal with the industrial civilization in yourself, and you have to do it here and now.”

That is what I call a rousing call to action.

*tips hat*

@Felix Cheah #39 Re: Odin/Woden and the Germanic Gods

JMG, if this is going too much off-topic, feel free not to put through.

Felix, if you’d like to ask a Heathen about Odin/Woden/Wotan, feel free to reach out, either by email (jeff DOT powell DOT russell AT gmail DOT com or at jprussell.dreamwidth.org). The super short version: To get a feel for Him, the best starting source I can recommend was one of Wagner’s primary sources, Snorri Sturlusson’s Prose Edda, and many of today’s Heathens (myself included) have found Him very responsive. If you’d like to dig deeper on either, reach out as I said and I can likely give you far more than you want or need!

Cheers,

Jeff

May I interrupt momentarily to ask how rhe 5th-Wednesday topic voting is shaping up?

Alex, I’d like to suggest another way of looking at it. Civilizations, ecologically speaking, are the human equivalent of early successional stages — they spring up where there’s an abundant supply of nutrients, run through it, and then die out, to be replaced by more stable forms. Our stable forms are various kinds of dispersed tribal communities. It’s all very sustainable, so long as you look at it in terms of the ecological big picture; civilizations fill their niche, and other social forms fill theirs.

Clay, interesting. Thanks for this.

Other Owen, in a very real sense, yes!

Justin, if I were a Viking I’d wax wroth at that comparison. No, not Vikings of the mind — they’re at the other end of the historical arc. Think of them as decadent Roman aristocrats of the mind:

Scotlyn, oddly enough, I meant it simply as a statement of fact. But thank you!

Your Kittenship, Hitler conquered it. We’ll be hearing from him — or rather from his posthumous image and reputation — in a couple of weeks.

Gotcha. Cuing up soundtrack to Fellini’s Satyricon…

“most of their ancestors dropped their language and culture like a hot rock ”

That’s an intriguing comment. My Scottish ancestors who landed in Cape Breton didn’t drop their language or culture at all, quite the opposite, to this very day you can find centenarian Gaelic speakers out there in the wild. I always wondered why there wasn’t more of this elsewhere given the vastness of the Scottish diaspora.

Anyway the Clearances are interesting in that you grow up reading about it, because it’s part of your heritage, and you think, “Pshaw, how terrible, good thing nothing like that would EVER HAPPEN NOWADAYS, amirite?” And then you look at various pieces of “environmental” (in scare quotes) legislation, or the current stories coming out from North Carolina, or what have you, and you realize: plus ça change.

Another great essay. Your zeroing in on Alberich’s curse as the dramatic (and musical!) high point of the opera is, IMHO, spot on. (People can listen to it beginning an hour and forty one minutes into the Youtube mentioned two weeks ago: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yFCFq6WWmGE — what the characters are singing is spelled out in clear subtitles.). Wagner had this uncanny ability to get into the minds of dark, twisted, cursed characters and use his incomparable greatness as a composer to enable us to feel exactly what they feel. Who else could do that? Well, Shakespeare, I suppose — and Verdi pulled it off in his most “Wagnerian” opera in his musical portrayal of Iago. But Wagner managed it over and over again – indeed the first piece of indisputably great music he ever wrote is “Die Friest Is Um” from the Flying Dutchman ; you feel the Dutchman’s rage and hopelessness (Wagner wrote that aria before he composed the rest of the opera; here is Bryn Terfel doing it in a bravura performance: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zcu11tVDy_s ) As mentioned before, I have some quibbles about Rheingold, particularly the opening parts with the Rhinemaidens swimming around the gold (yawn!); Alberich’s theft of the gold just seems to lack the power it should have. The trick Wotan and Loge use to capture Alberich — having him boast about being a toad — hmm, are we supposed to be afraid of this guy? But everything from the time they drag him up to the heights until the end of the opera has such incredible musical/dramatic power.

I guess in your next installment you’ll start in on Die Walkure. Can’t wait!

Adding to what Clay Dennis was saying about Japan, having been successfully attacked from the outside and forced to deal all of a sudden with the modern world (which they’d received considerable news from via Nagasaki, and had doubtlessly formulated a strategy for if worst came to worst), they noted the duality in the West between “Human” and “Nature,” and that it was a powerful concept, allowing the West to objectify the latter and exploit it. So the took the old word “Jinen” 自然, meaning “nature” as in “that is the nature of things,” and assigned it a new pronunciation: “shizen,” meaning that part of it which is separate from humans, unspoiled, all the meanings the West associates with it. They went ahead with that to modernize themselves.

Shinto never really adopted that concept. My first mentor, a robust guy who would climb a mountain even with his heart failing him, told me it was humanity’s duty to get out there and clear paths through the forest. The human-enhanced traditional Japanese landscape (described under the term “satoyama”) has higher biodiversity than places that are just allowed to go wild. Our foraging activities and attempts to maintain order create important niches, and have done so throughout our species’ existence. He told me, “We are an important part of so-called Nature.”

It strikes me as a healthier and happier attitude overall.

Patricia,

I completely agree with that attitude. I lived in the Japanese countryside for 3 years and found myself wanting to protect that version of nature much more. By that version of nature, I mean the version of nature that has vending machines and trashcans in the middle of trails located in the middle of nowhere, staircases next to a series of waterfalls, and manmade lakes with running trails around them in the middle of forests next to the ocean. There were very few people where I lived, with a density of only 69 people per square mile, and I got to experience nature in a way that I didn’t realize was possible.

Justin, you could do much worse as a model.

Bofur, there’s always an exception that proves the rule and Cape Breton is the one in this case; I don’t know offhand of another area where Scots immigrants kept the language and culture that tenaciously. My family had already dropped its name before they fled Scotland — as you may know, having the last name MacGregor was a death penalty offense in Scotland for almost 200 years — and shed everything else as quickly as possible once they got to this side of the Atlantic. I wouldn’t even know that my paternal ancestors were Scots if it wasn’t for my great-aunt Alice, who was a major genealogy geek. (Autism runs in the family.)

Tag, The Flying Dutchman is a fave of mine; “Die Friest ist Um” is a glorious aria, but for me the part that is most electric is the opening of the Overture: it’s an act of pure elemental sorcery, conjuring up a storm at sea more perfectly than any other piece of music ever written. (That Overture, btw, was the inspiration for much of my novel A Voyage to Hyperborea.) Musically speaking, The Rhinegold is hampered by too much theory, but Wagner shakes himself out of it as he proceeds, and the whole of Scene 4 to me is fine work. I’ve been amused to note that humming Donner’s invocation of the storm is a way to chase any unwanted piece of music out of my head…

Patricia O, thanks for this. Your first mentor had the right idea — the one that all of us will have to get back to. Do you happen to know if there are good English-language resources on the concept of satoyama?

@Siliconguy #52 I am very familiar with the Bible and through selection of verses ( including some things Jesus said in the Gospels) I could preach a convincing message about the loving and merciful God of the Old Testament in contrast to the judgmental God of the New Testament. Mercy and wrath, love and judgment run intertwined throughout the Bible. God is portrayed as both Lion and Lamb, a danger and a safe haven.

About Scotland and its diaspora, people always talk about the potato famine in Ireland in the 1840s but they forget that there was a potato famine which was occurring at the same time in the Scottish Highlands, which lead to a lot of Scottish refugees and immigrants to all around the world and the depopulation of the Scottish Highlands itself.

So, to obtain power, you need to relinquish love. I wonder if the opposite is true – you need to give up power to find love? I heard a saying that in a relationship you can either be right or be happy. Trying to overpower the object of your love may not be the best recipe for a happy, loving relationship.

Yes, back to the land away from the oppression of the capitalistic technological, artificial reality. But, hmm, we still need to go to town to get rolls of toilet paper – actually made possible by artful technology and more socks and clothes as ours wear out and …… and …… and. …. canning jars to store our vegetables,those jars would be marvels to most people through history – so clear, so exactly made and . . . . to get all sorts of other items we need. We are trapped in the belly of a beast.

Hi JMG and everyone,

Another great installment!

Regarding Tolkien, it now makes sense that he always said that his involvement in WW 1 was not the inspiration for his LOTR novels.

Apparently the ongoing march of industrialization was, so that ties in with Wagner.

I’ve been pacing my reading with this series, including a chapter of Schopenhauer here and there.