In this and the posts to come I’m going to be presenting a social, political, and economic interpretation of what’s going on in the operas composing Richard Wagner’s opera cycle The Nibelung’s Ring. Now of course the usual reaction to such interpretations is to back away from the crazy person as quickly as possible, and there’s good reason for that.

Crackpot interpretive schemes go back a long, long way. From the Pagan mystics who redefined the raucous behavior of the Greek gods as prim metaphysical parables, through the economist who published a lengthy book trying to prove that Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark was all about the business cycle, to today’s ongoing efforts to turn ancient mythologies into fourth-rate science fiction about ancient astronauts, this kind of allegorical interpretation can be very entertaining in a giddy sort of way, but it tells you more about the contents of the interpreter’s head than it does about the thing being interpreted.

There’s an exception to that rule, however, and that’s when the creator of the work under discussion intended the allegory. Nobody argues about whether there’s a subtext of Christian theology in John Bunyan’s famous The Pilgrim’s Progress, for example. Bunyan himself put one there, and made it impossible to miss. The main character’s name is Christian, he sets out on his journey after meeting another character named Evangelist, and away we go. It’s a fine romp, with villains, monsters, and perils aplenty, and you don’t have to be a Christian yourself to enjoy it, but there’s no question that Protestant theology is what it’s all about.

Richard Wagner was a little more subtle than John Bunyan. (It would admittedly take heroic efforts to be less subtle than Bunyan.) He didn’t name his characters Proletariat, Intelligentsia, and so on; instead, he took names, incidents, and decor from the Dark Age legends we discussed in an earlier post in this sequence. Nonetheless, as we discussed in a different post, Wagner was powerfully influenced by the philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, who redefined gods as collective cultural ideals. In his voluminous letters and other writings, Wagner made it as clear as anything can possibly be that this was what he had in mind when he went to work on The Ring. His gods, giants, nature spirits, and Nibelung dwarfs were symbolic stand-ins for the major players in nineteenth century European culture.

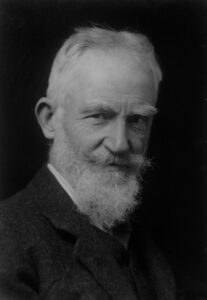

We have, as it happens, another witness to the same point, and it so happens that the witness in question shares three things with Richard Wagner. First, he was an immensly influential cultural and artistic figure in his time; second, he was just as far over onto the leftward end of the political spectrum as Wagner was; and third, he had one of the few egos of the age as insanely overinflated as Richard Wagner’s. Yes, we’re talking about George Bernard Shaw, playwright, essayist, literary critic, insufferable intellectual snob, and crazed Wagner fan. Among Shaw’s prodigious literary output, accordingly, is a short work entitled The Perfect Wagnerite. (It’s long out of copyright and so you can download a free copy here.)

Now in fact Shaw was an imperfect Wagnerite, though since he was Shaw there was no possible way he could have noticed this, much less admitted it. He was astute enough to catch the grand political and cultural subtext to The Ring, and thorough enough to read Wagner’s own writings and get the details of the allegory straight from the Nibelung’s mouth. In the present context, he suffered from two great limitations. The first was that he was utterly unable to imagine that anybody who disagreed with him could be right. The second was that he never outgrew the Feuerbachian optimism that was knocked out of Wagner by the aftermath of the failed 1849 revolution, and so his response to Wagner’s mature thought was to insist airily that Wagner was wrong and knew it, and had abandoned his social and political themes and lapsed back into ordinary opera in the third act of Siegfried and the entirety of The Twilight of the Gods.

There’s a tremendous irony in this notion of Shaw’s, and it’s one we’ll discuss in detail once we get to The Twilight of the Gods. For the first two and two-thirds operas, however, Shaw’s a helpful guide. Here’s what he says about our theme:

“The Ring, with all its gods and giants and dwarfs, its water-maidens and Valkyries, its wishing-cap, magic ring, enchanted sword, and miraculous treasure, is a drama of today, and not of a remote and fabulous antiquity. It could not have been written before the second half of the nineteenth century, because it deals with events which were only then consummating themselves. Unless the spectator recognizes in it an image of the life he is himself fighting his way though, it must needs appear to him a monstrous development of the Christmas pantomimes, spun out here and there into intolerable lengths of dull conversation by the principal baritone.”

He’s right, too, and goes on to demonstrate this in fine detail. With this in mind, we proceed to the first, shortest, and most transparently Feuerbachian of the four operas of The Nibelung’s Ring, The Rhinegold. If you haven’t read the libretto yet, stop now, download it here, and read the text of the first opera before we go on.

Ready? The orchestra is finishing the prelude and the curtains are going up on Wagner’s world.

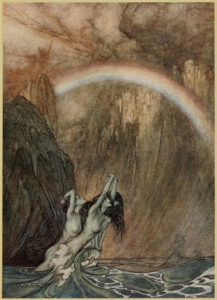

It’s a world on three levels. There’s the world of nature, here represented primarily by the Rhine flowing endlessly from the Alps to the North Sea. Later on we’ll meet some of nature’s other inhabitants, but the ones that matter in this opera are the Rhinemaidens, three water spirits named Woglinde, Wellgunde, and Flosshilde. Their great joy is a lump of magic gold, the Rhinegold of the title, which sits on a crag deep under the river, and their job is to guard it. They don’t take that job very seriously, because they know that only someone who has renounced love can take it and turn it into a ring of power, and the thought that anyone would do that seems absurd to them. So they dance and play in the water and wait for the sun to shine on the gold.

Down below the world of nature is Nibelheim, the world of the Nibelung dwarfs. They’re straight out of European folklore: short, scrawny, tough, and hard-working. They like to make things, and if you happened to visit Nibelheim before the beginning of the opera you’d find them laboring away, coming up with all kinds of clever items to meet their personal needs or just for the fun of it. We’ll meet a couple of the Nibelungs shortly, Alberich and his brother Mime (that’s pronounced Meemeh, by the way—he doesn’t wear white makeup and gloves or pretend to be trapped in a phone booth).

Finally, up above the world of nature is the realm of gods and giants. The giants are big, strong, and dumb. So are some of the gods, which is not surprising since they’re closely related to the giants—even in the Eddas, a lot of gods have giant wives or ancestors. Then there’s Wotan, whose actions set the whole story in motion. He’s not satisfied with the way things are, and in the usual way of things, his ideas for changing them start with putting himself in charge of it all. Back before our story opens, he maneuvered himself into the position of king of the gods; he married Fricka, the goddess of social custom, so he would have that immense power on his side; he dominated Loge, the tricksy fire-god of intellect, to have that second immense power on his side; he cut a branch from the World-Ash Tree, and onto it carved in runes the contracts and agreements that define his power; and he has just hired two giants to make him a palace.

All three of these realms, divested of their fairy-tale accoutrements, were everyday realities to people in nineteenth-century Europe, and they are just as essential to our lives today. The world of nature isn’t quite as full of treasures now as it was in Wagner’s time, since we’ve stripped so much of it to the bare riverbed, but nature and its guardians are still present. You don’t have to think of them as nature spirits if you don’t want to. Tribal peoples who live close to nature fit the pattern just as well—and as we’ll see, they and the natural world itself are just as vulnerable to the machinations of Nibelungs and gods alike as they ever were.

The division between the other two worlds was much more obvious in Wagner’s time than it is today. In those days the line between the lower and upper social worlds was explicit. Did you have enough investment income that you didn’t have to work for a living? If you did, you were on the gods’ and giants’ side of the line, and if you didn’t, you were on the side of the dwarfs. Read any novel from that time and you can see that line; it’s about as subtle as the Great Wall of China. That’s why Marxists are so obsessed about capitalism. When Marx wrote, possession of invested capital was literally the most important fact in European social life. Equally, one of the reasons why Marxism is so irrelevant these days is that we’ve moved on to a managerialist system, in which access to power and wealth depends mostly on bureaucratic rank, though capitalists of the old school linger on the way aristocrats did in the era of capitalism proper.

As the curtain rises we’re just before the dawn of the capitalist era. The Nibelungs are peasants, and the giants are aristocrats and gentry. The gods? They’re cultural figures: intellectuals, artists, celebrities, priests, and prophets, all those dazzling figures who not only entertain the giants but provide the ideas and images that define the world for the other characters. What holds this world together, in the final analysis, is love.

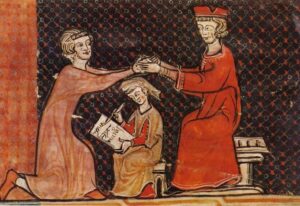

Does that seem unbearably romantic? It’s nothing of the kind. The medieval world out of which the capitalist world evolved was held together, from top to bottom, by personal relationships. That’s the foundation of feudalism. A feudal system is a network of personal commitments made between individuals. The baron and his vassal clasp hands, the baron grants the vassal a certain piece of farmland, the vassal grants the baron his services during wartime, and the glue that holds the feudal world together hardens around them.

All this descends straight from Gunther’s day. In the twilight years of the Roman world, when runaway corruption had gutted the last trace of the ideals that once made Rome strong, when the currency had become debased to worthlessness and government had been reduced to a system of organized plunder, the only thing that still held fast was the personal commitment of members of a band of warriors to each other and to their leader. The comradeship and mutual loyalty of men who have faced death together is a powerful bond; it’s not always powerful enough to resist the corrosive pressures that emerge during the fall of a civilization, but those warbands that fail to maintain it crumple in the face of battle and are erased from history. Those who succeed in the face of that challenge become the seed crystals around which a new world takes shape.

That bond of personal commitment, in turn, becomes the template around which the rest of society takes shape. It structures the relationships of every person and every social group to the others, and it also structures the relationship between humanity and nature. You can see this in the sort of old-fashioned farmers who still get their hands elbow deep into the soil: their relationship to their land is personal, not abstract. You can see it even more powerfully among surviving tribal peoples, for whom every feature of the land is a person, with whom human beings not only can but must establish and maintain mutually respectful relationships.

This kind of personal relationship, uniting individuals with one another, with their society, with their ancestors and gods, and with the natural world, is the basic form of human society. It’s the form from which every more complex and abstract system arises, and the form to which every such society reverts once it goes through the usual arc of rise and fall, and ends where it began. To begin that arc of rise and fall, in turn, the one thing that has to happen is precisely what starts the action of The Ring: someone has to break the web of relationships in a way that can’t be repaired by those who are still committed to it. Someone has to renounce love.

That’s what happens, of course, in The Rhinegold. As the curtain rises, we see the Rhine, with the Rhinemaidens cavorting through the water around their golden treasure. Then a Nibelung named Alberich comes scrambling up among the rocks on the bed of the Rhine and catches sight of the Rhinemaidens. Of course he falls instantly in love with them. Of course, since they’re lovely nature spirits and he’s an ugly little Nibelung dwarf, they aren’t interested. Nor are they nice about it. They tease him, flirt with him, and then mock him for his ugliness. In its own way, despite the beauty of the music and the humor of the drama, it’s a brutal scene, and the effect on Alberich is just as brutal, as his clumsy affection crumples into bitterness and misery.

Any of my readers who grew up homely and socially clumsy, as I did, know this song well enough to sing all the verses by heart, but there’s more going on here than a savage commentary on common social habits. The great vulnerability of human relationships with nature is that the affection is one-sided. You can adore the piece of ground you farm, you can pour all your heart and soul and love into it, and yet a few days of bad weather or a summer that’s just slightly too dry can mean a failed harvest and a year of privation and misery.

That’s what Alberich is going through. A lot of people went through it in Europe in the centuries prior to Wagner’s time. Europe, that bleak, mountainous, storm-swept subcontinent stuck onto the western end of the continent of Asia, is a difficult place to maintain an urban agricultural civilization. If you’re on the southern edge of it, up against the Mediterranean, it’s not so bad, though you can count on catastrophic droughts fairly often. If you’re north of the ragged band of mountains that extends from the Pyrenees across south central France to the Alps and then down the spine of the Balkans, on the other hand, you’re in much worse shape.

It’s worth remembering that southern Germany is at the same latitude as Newfoundland and northern Germany is at the same latitude as Labrador. Only the Gulf Stream and certain unstable weather patterns triggered by that great oceanic river of warm water keep it from being subarctic wasteland better suited to musk oxen and caribou than to agricultural crops. From 1500 to 1800, those weather patterns were much weaker than usual, and at irregular but frequent intervals, Europe shivered and starved. That’s the Little Ice Age that climate historians discuss. It was also the great driver of the age of European mass migration: millions of families gave up everything to flee to other parts of the world where they hoped to find a better chance of survival.

The Little Ice Age was also what shattered what was left of the peasant economy of old Europe and brought about the rise of industrial capitalism. As the Little Ice Age was hitting its stride, Europe was fighting for its life against the armies and navies of the Ottoman Empire, which made no secret of its plans to conquer the European subcontinent the way the Mughals had conquered India. The struggle to maintain naval parity with the Ottomans was one force that drove European shipwrights to push the boundaries of their craft, inventing new ship designs that were far more sturdy and maneuverable than anything else afloat. Another force was the desperate struggle to keep Europe fed, in which vast amounts of salt codfish from the western Atlantic fisheries played a vital role.

Merchants who invested in the new ships then discovered that they could ship sugar, tobacco, slaves, and other valuable cargoes all over the world, amassing vast profits. Those profits, in turn, allowed them to seize control of whole sectors of the economy, replacing local crafts with centralized factories whose products could be shipped all over the planet. At first, those factories were powered by waterwheels; that’s why, for example, you’ll find a belt of old factory towns all along the North American seaboard at the “fall line”—the point at which rivers tumble down out of the foothills of the Appalachians onto the coastal plain, where upriver navigation stops but there’s still enough of a slope to give waterwheels ample power.

That was the first wave of industrialism: the eotechnic era, as Lewis Mumford termed it in a fine and unjustly neglected book. It caused immense changes, to be sure, but its reach was limited in geographic and energetic terms. There are only so many good sites for waterwheels on the planet, and it’s only possible to extract a sharply limited amount of mechanical energy from them. Wind could pick up some of the slack—the Netherlands famously specialized in this—and also provided transport, filling the sails of tall ships. Here again, though, there’s only so much wind and it can only accomplish so much.

Then, of course, Alberich stole the Rhinegold.

Gold wasn’t actually the thing that mattered, though it certainly looked that way to George Bernard Shaw. In his time and Wagner’s, European currencies were all gold-backed. Gold was the great talisman of wealth, which is why the nineteenth century saw so many gold rushes around the world, and why one of my great-granduncles abandoned his failing farm near the shores of Grays Harbor, Washington to go to the Klondike in the hope of getting rich. Far more important, though, was coal—King Coal, as it was called at the time, the single most valuable mineral resource in the nineteenth century, the foundation of the second wave of industrialism: the paleotechnic era, as Mumford called it.

Coal was crucial. Once steam engines powered by coal replaced waterwheels powered by the local equivalent of the Rhinemaidens, the industrial system could metastatize across Europe and eastern North America, shattering what remained of the old economy of personal relationships and local loyalties, and replacing it by a system in which the only relationships that mattered were economic. That said, it’s a mistake to see the Rhinegold as any one commodity. The theft of the Rhinegold, rather, is the process of commodification as a whole—the replacement of personal relationships with market forces, in which everything (including human lives) became just another set of raw materials to be exploited for profit.

That’s the process that Alberich’s deed kicked into motion. He didn’t start the process, though, nor was he the only participant. We’ll talk about that two weeks from now.

* * *

It occurs to me that there are five Wednesdays in this month, and by longstanding tradition, the commentariat gets to vote on what I write about for the fifth Wednesday. What do you want to hear about? Enquiring Druids want to know.

“In the twilight years of the Roman world, when runaway corruption had gutted the last trace of the ideals that once made Rome strong,” Ouch.

“when the currency had become debased to worthlessness” Oof.

“and government had been reduced to a system of organized plunder,” Eek.

“the only thing that still held fast was the personal commitment of members of a band of warriors to each other and to their leader.”

You really know how to drive in a knife. I don’t think the local war band is hiring yet, but I’m not optimistic about avoiding that event.

To which of Lewis Mumford’s books (I am a fan, for what that might be worth) do you refer?

For the 5th Wednesday or at some other time, I would like you to elaborate on your remarks about the Reformation being inspired by Islam. There were many heretic movements throughout the Middle Ages, the Albigensian being only the best known, but before Luther, the Church in alliance with secular authority always managed to prevail. What broke apart that alliance? Contemporary Catholic writers allege greed for monastic lands; feminists blamed desire of monarchs to have all females married and breeding future soldiers.

“Europe was fighting for its life against the armies and navies of the Ottoman Empire, which made no secret of its plans to conquer the European subcontinent the way the Mughals had conquered India. ” Thank you for this, a fact of history which is obscured when it is not ignored altogether amid vociferous complaining about “Crusaders”.

I nominate for the 5th Wednesday the topic of America’s obsession with HItler.

As I mentioned previously, my vote for the fifth Wednesday post this month is your thoughts on the nature of the new elite that will arise to replace the one that we currently have. Also, possibly any thoughts how to deal with the transition that you have not covered previously.

Howdy,

Very much enjoying these posts, I’m glad you decided to “scare off all your readership” 🙂

As for the Fifth Wednesday, maybe “Jung as an occultist” can finally get its day in the sun. I’d be especially interested in how the archetypes fit into occult philosophy and practice, but please count this in with whatever other focus you or others would prefer in talking about Jung.

Cheers,

Jeff

I would like for you to write a post about kundalini rising – what it is, how to know if it is happening, and how best to respond if it does. You’ve mentioned going through it; so have some of your readers. I don’t think I’m the only one of your readers who would like to know more about it in case it happens to us.

JMG,

Thanks for spurring me to go through the Ring Cycle – I’d avoided it for years, since I’ve always disliked operas. My experience with operas previously had been that they take a very long time to tell simple and uninteresting stories against dull backdrops, and the Ring Cycle being the epitome of ‘opera’ in popular culture, I figured it was the same but more.

I was very wrong, and have definitely become a fan since watching/reading them. I’ve been listening to an instrumental version more or less nonstop for the past few weeks.

I’ll have to disagree with Shaw, while I may be new to Wagner, it’s obvious that the final third of the cycle is what makes it true art and not just a “Christmas pantomime.”

I’m sure the weaponized autists of 4chan can find some sympathy with Alberich. His plan for world domination echoes what Jordan Peterson calls ‘revenge against the world for the crime of being.’

Uff, was just able to make a pass trough Wagners Ring cycle for the timing of this post and am still digesting it.

As for the fifth Wednesday. May I be a persistent pest and again try to suggest Hitler as an archetype as per last years offer “One of these days, when I’m ready to have a very large number of people melt down completely, I plan on doing a post about Hitler as archetype, …”

Ecosophia

In November we voted on it, and lost to a wonderful theme

Case Study of Chinese collapse resilience

And again in July to The Neckless Ones: A Historical Puzzle

All interesting pieces that I reread multiple times in the last months.

But still the stars may have come around right this time, so I repropose to raise the “Hitler as archetype” once again.

Best regards,

Marko

That’s an excellent point about the Ottoman effort to conquer Europe. My history courses in High School and College made no mention of it at all, despite its enormous historical importance.

I learned about it only in my early 20s, beginning from a small piece of paper pinned to the bulletin board outside the office door of one of my professors in Slavic linguistics, commemorating the anniversary of the the victory of King John III Sobieski over the Ottoman armies in 1683 at the “Gates of Vienna.” Intrigued, I went to find out more. That victory turned out to have been a very close call indeed: Europe had been within a hair’s-breadth of becoming just one part of the Ottoman Empire.

Later I began to wonder why my history courses never went there. That led to some quite worth-while private meditations on the pseudo-discipline of “Western History” (as id “The West” were a genuine “thing” in history)., and also on deliberate blind-spots in academia and the reasons for their deliberate creation.

There’s a pretty good wikipedia article on the event itself under the heading “Battle of Vienna.”

I don’t know of many people who considered “Pilgrim’s Progress” enjoyable. My brother had to read it in school and hated it. I read it out of curiosity and thought, “so that’s where Vanity Fair originated”! Hawthorne’s parody was really not up to his usual standard. Fortunately, he kept it short. Your joke about mimes made me chuckle. For the 5th Wednesday, I’d like your take on Mercurius.

Hello JMG. Excellent post as usual.

I was raised in one of those liberal protestant churches where well educated pastors preached a religion they did not seem to take seriously. I have been watching the swell of the second religiosity begin to rise in this country and think that it might be an opportunity to reconcile the religious and occult ways of viewing the world. I do not know if this would serve as a seed of a topic for the fifth Wednesday or not. If not, do you have any suggestions for sources (books, practicioners etc.) on learning an effective, responsible occult practice rooted in Christian faith? It is past time to reclaim those sacramentals for the future we seem to be getting ready to face. Thank you.

I second the request for a posting about kundalini rising but will bow to whatever the majority decides.

And unless my aging eyes deceive me, your photo posting of the grist mill is none other than the one located in my hometown. If anyone is interested in its history, it was operating until the 1930s. A small dam, now long gone, powered it. Fallen into disuse, it was renovated and opened as a working grist mill and museum back in the 90s. Regrettably the lease wasn’t renewed and it closed. Now it is occupied by the Schilling Beer Co., a local brewery using it as their pub and kitchen.

JLfromNH/Viridian Vitriolic Ouroboros

For the 5th wednesday i also name America’s obsession with HItler.

We all should also remember that if the rhinegold was, in the end, coal (appropriate considering the huge coal reserves that were there), we are into even more dangerous drugs nowadays with oil. If coal spread industries all around Europe, N.America and West Russia, oil removes the last restrictions that the rhinemaidens held upon coal: coal is heavy and coal does not pack as much energy per kg as oil, making transcontinental coal trade, in those days, nearly unprofittable (even if some colonial powers used their colonial opression to ship coal from the colonies to Europe). With oil you can create an industrial Mordor (ie. Las Vegas) anywhere, breaking the last chains of nature. Until the oil runs out and you die.

Re the climate of northern Germany.

In 1980 I worked for a German boss in Namibia. He told me he had grown up in a small village in northern Germany. In winter the snow was so deep they were cut off from the outside world for months at a time. There was no question of going to the shop for fresh fruit and vegetables because no trucks could get through. Sauerkraut provided their needed vitamin C. They rented a field from a farmer, planted cabbages, and when the cabbages were ready the whole family got together and harvested them and made sauerkraut. They had a special sauerkraut plane that was placed on top of a barrel and they shredded the cabbage directly into the barrel. When they were finished and the barrels stored in the basement to ferment there was a big party because they knew they were safe for another winter. This would be somewhere around 1940-50, based on the boss’s age.

I vote (yet again) for the Austrian corporal with the moustache and the Nazi ventures into the occult.

Am I the only one who finds it incredible that people are surprised that a plot set in motion by someone getting an object of power by renouncing love would end badly? The idea that Wagner thought this could be anything other than a tragedy, and Shaw could see this and think Wagner was wrong for making it into one just seems complete insane to me….

Ah, George Bernard Shaw, the British intellectual who outdid most of his peers by publicly celebrating both Hitler and Stalin. The others normally took up one of those at most. He certainly had some talent for… provocative writing, though. I either didn’t know or forgot that he was a Wagner fan, but it makes sense that he would interpret him in this specific way.

“[Wotan] has just hired two giants to make him a palace.”

If a god is an influential celebrity and giants are aristocrats, I suppose this is like, say, a famous composer getting sponsored by a mad king? 😛

And I suppose I’ll vote for the cultural legacy of the Bohemian corporal. It’s a topic that just won’t go away (I don’t mean here, but in the world at large), so I’d be interested to hear what you think of it. Come to think of it, one of the angles I find most interesting about it is “how much longer will he be around”. I have this grave suspicion that it would take a drastic collapse to shake him loose, and even then it isn’t quite a sure thing. Jews still remember Haman, after all.

I’ve tabulated everyone’s nominations for Fifth Wednesday topic. Thank you all!

Siliconguy, it’s history’s hand on the knife, not mine. Warbands are already hiring, but as usual, they’re mostly putting out their help wanted signs on the other side of the border.

Mary, I’m delighted to hear it! Mumford deserves much more attention than he gets. The book in question is Technics and Civilization, published in 1934.

Sirustalcelion, you’re most welcome and thank you. Wagner is actually the antithesis of opera — he would have been the greatest of all movie producers, except for the minor point that cinema hadn’t been invented yet. He loved all the things that made for great movies in the golden age of cinema: grand vistas, lively plots, colorful and conflicted characters, and good theme music. As for Alberich, yeah, I think “Nibelheim” is how you spell “4chan” in German.

Robert, it amazes me that it’s been erased as thoroughly as it has. Early modern European history only makes sense if you remember that Europe was an impoverished and politically fragmented region fighting to maintain its independence against the huge and culturally more sophisticated Ottoman Empire. It’s the same situation the Greeks faced two millennia earlier when they had to carry on the same fight against the huge and culturally more sophisticated Persian empire — and in both cases the victory of the underdog sparked a cultural surge and an era of colonial expansion, both of which transformed the world. These…

…were the precise equivalent of these.

Phutatorius, hmm! I found it readable enough that I’ve reread it several times. Still, no accounting for taste.

James, that’s an easy one. Your first source is Experience of the Inner Worlds by Gareth Knight — he was one of Dion Fortune’s students, and also a devout Anglican Christian. This book of his is a great introduction to Christian occultism. After that, Peter Roche de Coppens is worth close study: his book The Nature and Use of Ritual is all about using the standard Christian prayers and creeds as central occult practices, and his Divine Light and Fire is a solid intro to esoteric Christianity. If you want to go further, you might see if you can find a local Martinist chapter — Martinism is an esoteric Christian initiatory tradition, and there are various Martinist orders in the US and elsewhere these days.

Jeanne, hmm! Thanks for this; all I knew was that it came up when I did a search online for industrial water mills.

Luciano, oh, it’s worse than that. Oil was supposed to be a bridge to the utopian nuclear future, another round of Rhinegold giving even more limitless power. Unfortunately it turned out to be a bridge to nowhere.

Martin, that sounds about right. Might be time for readers to begin honing their sauerkraut skills — either that or kimchi, which did the same valuable service for farm families in wintry Korea.

Taylor, ah, but the Romantics believed that the world created by Alberich’s lovelessness could be overthrown and replaced by a world based on love. It never occurred to them that their ideologies were just as loveless as the ones they hated. We’ll get to that…

Daniil, good. Very good. Yes, Shaw’s bad judgment was as monumental as his ego!

Phutatorius, I couldn’t stand Pilgrim’s Progress. I am still, decades later, amazed that I read it to the end.

Robert Mathiesen, someone once asked on this forum, or maybe its predecessor, about use of magic in history. the person might want to look at the Battle of Lepanto. The Moslem admiral, newly arrived from the reconquest of Cyprus, had a large green flag embroidered with all 99 names of Allah. On the Christian side, Don Juan of Austria had himself rowed with a giant crucifix to each ship to have the carving blessed. Mass was celebrated on every ship before the battle–battles were much slower then than now, and there was a lot of preliminary maneuvering, see Patrick O’Brien for good descriptions– and Don Juan had the crucifix affixed to the mast of his flagship. There may have been some blowback in that during the conquest of Cyprus, which was a matter of taking over some castles, ordinary Cypriots had nothing to say about whom their masters were going to be, one castellan refused repeated demands to surrender, and was finally subjected to a most gruesome execution by the annoyed conquerors. Two of the dead man’s brothers were squadron commanders at Lepanto, and I rather think dying curses were a thing people believed it in at that time.

Dear JMG: Thank you for another fascinating post! Your comment on the Little Ice Age as a cause of European mass migration caught my eye. I think this is right, but also understood the Enclosure Movement, and the general move away from commons and towards private property in Europe as also being important instigators of migration. Do you see these as related?

The discussion is particularly relevant in today’s political discussion about migration. As someone who spent many years in Latin America starting in the 90’s, I saw how the modern version of enclosures – opening up farmland to large multinationals – drove poor and middle class farmers out of business and into urban slums or northward to seek a better life. It’s a conundrum our politicians don’t want to recognize today as they face blowback from mass migration. Welcome your thoughts!

My bet is that the warbands of neo-feudalism will come from mercenary groups and the drug cartels. The complicated relationship between the Wagner Group and the Russian Federation seems an echo of things to come.

As for a vote on the next topic, I would like to hear about your philosophy, how you harmonize Schopenhauer, the Taoists, Levi, and Fortune. I would like to hear about it in as much detail as possible. But perhaps that topic should be saved for a future date.

This has been a very thought provoking series of posts. I vote for Jung as an occultist, that certainly sounds like a fascinating thing to learn more about.

I vote for whichever topic has the highest number of votes and is NOT about Hitler.

Plenty of food for thought there!

Dear JMG:

My vote is for Hitler as archetype/ the west’s obsession with him.

By the way, a very nice picture of Polish pancerni cavalry! And history has an ironic turn; the Austrian Empire helped to erase Poland in the late 18th Century. Some gratitude!

Cugel

My vote for fifth Wednesday: your thoughts on why the United States’ upcoming 250th anniversary is being so studiously ignored.

JMG

My vote is for the Hitler archetype as well.

Thanks again for this series.

@JMG,

I haven’t commented on any of the Wagner posts yet but I do enjoy reading them. I’ll admit that my interest in Wagner is mostly from the musical side; until now I hadn’t given much thought to the politics of the Ring operas. (And I’d found Wagner’s cavalier handling of the old Germanic legends rather off-putting; I think Tolkien disliked the Ring cycle for the same reason.)

You said “The Nibelungs are peasants, and the giants are aristocrats and gentry. The gods? They’re cultural figures: intellectuals, artists, celebrities, priests, and prophets, all those dazzling figures who not only entertain the giants but provide the ideas and images that define the world for the other characters.”

To me this seems rather too clear-cut. Think for instance of Fasolt’s speech to Wotan in Act 2 of Das Rheingold:

Soft sleep sealed thine eyes

While we, both sleepless, built the castle walls:

Working hard, wearied not,

Heaping, heaving, heavy stones.

Tower steep, door and gate,

Keep and guard thy goodly castle halls.

That looks to me like the complaint of a lower-class person who works with his hands, not what a capitalist would say to one of the “cultural figures” that the Gods are supposed to represent.

Granted, it may well be that Wagner explained the allegory in the same terms you did – I haven’t actually read his letters on the subject, let alone Shaw’s book. Though of course it’s worth nothing that artists often think they’re putting political messages into their work that end up making very little sense to anyone but the artists themselves. (For instance, how George Lucas, when he was making Return of the Jedi, honest-to-goodness thought he had based the character of the Emperor on Richard Nixon.)

As you point out, Wagner portrays Alberich as a pathetic figure (no doubt the Rhinemaidens would use the word “incel” if the opera were written today) and seems to imply the whole brouhaha could have been avoided if one ugly dwarf had just accepted the limitations of his prospects and maybe gone off to OnlyFans instead. But if Alberich represents the peasantry and his humiliation represents their privation and misery due to the necessary realities of human interaction with nature, it does make him seem a bit more sympathetic. “The problem starts when the churls fail to starve gracefully enough” isn’t exactly cautionary, let alone prescriptive. I guess that’s part of the point.

To that point, and speaking of river spirits, some of the ones in western North Carolina and environs have given some of my relatives’ neighbors considerable trouble last week. In this case the reaction to such humiliation will probably result, in the long run, in dozens of modest Main Street bridges being replaced by flood-proof monstrosities and miles of scenic river bank being sheathed in concrete slabs, ultimately making the underlying problems worse. So the opera goes.

Once again, all votes (except for one — see below) have been tabulated.

Anna, the enclosure movement was driven partly by crop failures — sheep can thrive where wheat won’t grow, as every Scotsman knows — and partly by the explosive growth of wealth in the mercantile class, since they needed wool for their cloth mills. It was a complex phenomenon, but the Little Ice Age is rarely given the importance it deserves.

Enjoyer, the Wagner Group was a warband pure and simple. Prigozhin was ahead of his time; another generation or two and he wouldn’t have been anything like so easy for the Russian government to crush.

Kyle, nope. You don’t get to cast a negative vote. If you want to cast a vote you have to name a specific topic you favor, and then it’ll be recorded.

Patricia M, I do my best.

Cugel, nations have interests, not friends. Be that as it may, one of my favorite notions for alternative history imagines a Polish-Lithuanian empire absorbing most of eastern Europe.

Sandwiches, granted, there’s a lot of complexity in all Wagner’s symbols. I didn’t know that about Lucas — I gather he never heard about projecting the shadow…

Walt, exactly. I hope your relatives are okay.

For 5th Wednesday, I’d like to add a vote for kundalini rising. Though if you can give useful references now, that would also be helpful. I’ll ask on Magic Monday if that’s more appropriate, but I’ve been having (unintended) mental images arising lately of a snake uncoiling & slithering up my spine, and I’d like to be prepared to handle it healthily.

I’m another person who enjoyed Pilgrim’s Progress; it felt useful spiritually in the same way as Screwtape Letters, giving me insight into the journey ahead of me.

Fifth-Wednesday topic suggestion: Jung and his connections with the occult, with extra credit for at least a side-glance into The Red Book.

I cast my vote for a post on Lewis Mumford.

I am very much enjoying these posts on Wagner. All I knew about him before is that he wrote ‘The ride of the valkyries.’

My vote is for the Austrian corporal.

Will O

I’m reminded of the joke about an old lady watching Hamlet for the first time, and saying that she liked it, but there were so many quotations. Because reading the libretto, I was repeatedly & forcibly reminded of the One Ring in the Hobbit & LOTR. (Which reminds me, how much of the libretto should I plan to read in advance of the next opera post?)

I vote for Jung’s occultism.

Annette

Your writing often sets off sparks in my mind, and this is one of those times.

I’m currently watching the mini-series “Shogun,” and your discussion of feudal societies, war lords, naval power, trade, and the crucial role of personal relationships came vividly to life.. I highly recommend that series if one has not yet seen it.

Than you for another engaging and edifying post!

I’ve been really enjoying your discussion of Wagner, although I haven’t been commenting.

For the fifth Wednesday, I vote for why we’re — as a country — ignoring our 250th anniversary.

I remember the hoopla about 1776. It began years earlier.

And now? Crickets.

For the 5th

Hitler and the Wotan archetype.

Have you seen some of the AI translated English speech videos on YouTube?

They seem to get very interesting comments particularly from the young.

Thanks very much for this essay! After reading the libretto last week, I had some ideas in this direction, but you added much more detail, especially about the nature of the gold and of love. I admit I had only thought of romantic love in the scene with Alberich.

For us moderns, it seems as if the love between a war leader and his retainer is modelled on romantic love between men and women, but I have read (in Lewis?) that the love between men and (higher social class, married) women glorified by the troubadours and the Arthurian lays is actually modelled on the retainer’s love towards his leader. Idealized examples can be found many times in the Eddas and sagas, where retainers are willing to die for sadness after their leader was killed.

And a lot of interactions among commoners just as much as among the nobility were intertwined with relations of blood – affection towards one’s children, one’s parents, one’s brothers and sisters, one’s cousins and so forth. This often takes the form of what in our impersonal order would be considered nepotism or corruption. So yes, it makes a lot of sense, even though it sounds crazy, to say that the feudal order was based on love.

Speaking of corruption, I am not quite sure anybody in the ancient world considered the mingling of private and public money, or favouring one’s kin, a crime. It was just the way things were. In any case, a large part of the taxes continued to be used for the upkeep of the Roman armies, which were very rather rarely outright defeated by barbarian enemies. You are absolutely right about the oppression of commoners by taxes and other rules and about the debasement of the currency, though.

I voting for the Hitler topic. We have this item preserved from the New Republic (second picture down). It was famous for a bit after the assassination attempt.

https://twitchy.com/amy/2024/07/07/new-republic-cover-image-portrays-trump-as-literally-hitler-n2398094

And this, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/09/24/trump-hitler-rhetoric-comparison/

And this, https://www.gettyimages.com/search/2/image-film?phrase=trump+hitler

Just Google Trump as Hitler and it will flood you with hits.

Comrade Kamala isn’t trending nearly as strongly.

My 5ᵗʰ week vote is the mental health impact on people losing faith in Progress and the consequences following on from this.

I’m going to keep voting for Hitler until the post happens or I get accepted to art school… and I haven’t applied to art school.

@Kyle #23: I hear you!

My vote is for:

“the extent to which Protestantism is a Magianized form of Christianity, made over in the image of Islam”

I vote for Carl Jung!

Hi JMG,

I hope things are going well for you. Thank you for your writings‼️

> the commentariat gets to vote

Hitler.

💨Northwind Grandma💨🗳️🔥

Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

Once again, I recommend the novel “JR” by Wm. Gaddis. The protagonist, JR VanZandt, is a sixth grader who plays the role of Alberich in a sixth grade production of “Das Rheingold.” Without love or family, he builds a paper empire, the “JR Family of Companies,” acting as a corporate raider. All justified by his notion that “that’s what you do.” It’s a novel about music, greed and chaos (my own characterization). I enjoyed it. Apparently everyone except for Rick Moody considers it to be a difficult novel.

For once I’m voting for a Fifth Wednesday topic, and my vote is the same as Teresa Peschel’s (#38): “why we’re — as a country — ignoring our 250th anniversary.”

Thank you, Teresa. That seems to me to be one of the very few $25,000,000 questions these days. The symbolism of that silence feels very dire to me.

Hi John Michael,

Exactly, it’s not just one single commodity. To me it looks like everything and anything will get thrown under the bus to keep the big old wheels rollin’. Things can lurch though, I mean look what happened in Europe once king coal was no longer able to be extracted economically using human labour? Messy.

Far out man, but earlier in the year I was told “It’s just business”, when a very long term working relationship was abruptly severed. Sure, if they say so, but I’m pretty certain the Roman citizens opened the gates to Alaric I and his cohorts. There’d have been a good reason for that too, don’t you reckon?

Cheers

Chris

If Hitler gets selected for the 5th Wednesday (I haven’t decided my own vote yet), here is an interesting article on the Barsoom Substack:

World War Time Loop – Escaping the Myth of the Eternal Second World War

https://barsoom.substack.com/p/world-war-time-loop

The TL;DR version is that WW II (and Hitler) have been mythologized by the Professional Managerial Class, and this mythos forms the basis of their moral legitimacy and their (claimed) right to rule over the rest of us.

This means, that the reason why asking certain awkward questions about the actual events of that war has been criminalised in so many countries is not because “thuh Joo-o-oz” control everything (although they do have an out-sized influence). It is because the demythologization of that war would be the final nail in the coffin of the moral legitimacy of the PMC.

Hi JMG,

Could we do another post some time talking about nuclear power? Many people are still touting it as a common-sense choice for future energy installations (e.g. Michael Shellenberger), but the concept of EROEI suspiciously rarely comes up…

I am also voting for America’s obsession with Hitler.

Mr. Mathiesen re: #9 – I’d be honestly intrigued by an alternate history in which the Battle of Vienna went the other way, especially considering European colonization of the New World had already begun by that time. I don’t see the Ottomans managing to pursue full conquest all the way across the Atlantic without running into imperial overreach. (London to Boston is already quite the supply line, and the British had the benefit of loyalist Canada and other loyalist ports to fall back on; Istanbul to Boston is even longer and they won’t have friendly harbors.)

JMG – I wish to second Roldy’s vote for the radio silence regarding the upcoming sestercentennial.

Boy, you make feudalism sound mighty appealing….

As I had a few months back, I’ll propose for a fifth Wednesday topic to explore if Marx was a thumaturgist.

The Marxist ideologies must have the greatest marketing strategy in the history of ideas. They have proven disastrous time and time again, yet keep cropping up as “the next great idea.” It makes me wonder what magic do these ideologies (Marxism, communism, socialism, etc.) possess that allows them to continue to crop up in the popular imagination?

Add another vote for the Hitler topic.

Vote for Jung the Occultist

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Audrey’s nephew John, who passed away on 10/1 after an extended illness, be given comfort and clarity during his transition.

May Rebecca’s new job position now scheduled to start

on October 8th indeed be hers, and fill her and her family’s needs; may the situation (including coworkers and dodgy commute) be pleasant and free of strife.

May the lump in the breast of newlywed Merlin, TemporaryReality’s youngest daughter, prove to be of no consequence, and resolve rapidly with no issues.

May Kevin, his sister Cynthia, and their elderly mother Dianne have a positive change in their fortunes which allows them to find affordable housing and a better life.

May Tyler’s partner Monika and newborn baby Isabella both be blessed with good health.

May Erika be blessed with good luck and radiant health.

May Mariette (Miow)’s recent surgery have been a success. May she make a full recovery and regain full use of her body. May she heal in body, soul and mind.

May The Dilettante Polymath’s eye heal and vision return quickly and permanantly, and may both his retinas stay attached.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

I neglected to add to the list of highlighted prayers above:

May all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricane Helene in RandomActsOfKarmaSC’s state of South Carolina be blessed, comforted, and healed.

The Hitler archetype obsession please

I’ll add another vote to the Hitler topic.

JMG,

Voting for the lack of a 250th anniversary brouhaha as well.

Cheers!

So just to be clear, the West is obsessed with Hitler because they have made Hitler into a Wotan archetype?

My vote is for the fifth wednesday is again for the mysteries associated with the Mage John Dee. Exploring the potential that his workings set in motion events that led to the dominance of the British Empire. Also, analyzing the Enochian language and its occult source(s), and commenting on his turn of focus to magic as described critically in Shumaker and Heilbron’s ‘John Dee on Astronomy’.

Thanks fo continuing this series on the ‘The Nibelung’s Ring’!

“The medieval world … was held together, from top to bottom, by personal relationships… a network of personal commitments made between individuals.”

Wow– when you put that out there, current events at my employer massively clicked.

My company was founded and run by a couple of engineers. Knowing from the get-go that their bread was buttered by the people who worked for them, they established a culture of loyalty to their employees, which the employees returned with enthusiasm. Voluntary weekend work was commonly seen, “to make sure we pass next week’s inspection” and so on. There is, and I feel it too, a definite emotional bond between all of us– it’s not sexual love as such, but a strong tie nonetheless.

A couple of years ago the founders, perhaps because they weren’t getting any younger, sold it to another company from a different US subcultural area, whose managers turn out to be the epitome of the vicious PMC industrialist. These new rulers claim that “they don’t care about morale, they only care about the money” but what I really think is, they hate, with an incandescent purple hatred, any shred of culture which involves two-way, top-to-bottom loyalty, especially if such a company actually succeeds in business, because it puts the lie to their assertion that “the only way to get people to work is to beat them into submission”.

The culture of tyranny hasn’t gone over well among the rank and file and shirts bearing the old company’s logo are often seen in the halls. The banner bearing the new company’s logo, which had been draped over the old company’s logo on the front of the building, has mysteriously “blown away in the wind”.

All we lack is a war chieftain; if we ever got one, things could be very interesting.

I tried to listen to Wagner but I don’t find him as engaging as Mozart. I appreciate this series of posts though.

My vote for the 5th Wednesday post:

The limits of Spengler’s model, considering smaller cultures that don’t quite fit into the great cultures per se (Japan, Tibet, Central Asia in general etc)

I dunno folks– I don’t think Hitler can be an archetype. In order to be an archetype, your fans need to hijack a well-known religious icon, like the Buddha-Trump statues.

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/be-peace-meditate-trump-buddha-statue-designer-tells-former-president-2021-03-31/

Oh, wait–

https://www.amazon.ca/HITLER-CHRIST-Hakenkreuz-Hooked-Cross-Crucifixion/dp/1548098639

OK, OK, Hitler as an archetype could be a thing. Hope no one is burning candles to him…

@blue sun,

I believe JMG kinda addressed that before — Marxism adopts the apocalyptic vision of Christianity but applies it to this world instead of the afterlife. Immanetizing the eschaton. It is only one of the subschools of the civil religion of progress: https://thearchdruidreport-archive.200605.xyz/2013/09/which-way-to-heaven.html you can swap out Marxism for electric vehicles, fracking, solar power, EVs etc etc for the next brilliant solution that will solve the world’s problems

Seems to me that the magic, from a Spenglerian PoV, lies in capturing the (pseudo-)Faustian mind in its desire for Progress into infinity.

@Michael Martin, I didn’t read the linked article but the premise makes a lot of sense to me. I don’t know about other countries but here in Singapore, the history curriculum was explicitly created for “nation-building” and fostering a national spirit. The bugaboo we learned about in school wasn’t Hitler but the Japanese atrocities in WW2 and how we can’t depend on external powers for our own defence. From what I know of other countries’ history curricula, WW2 also seems to have a lot more coverage compared to any other period. I think this explains why most Americans don’t learn about the Ottoman invasions too. Perhaps the Austrian history curriculum would cover it. The Balkans’ history curricula definitely would cover the Turkish occupation there

For 5th Wednesday, I will vote for Jung and occultism.

I have a lot of time for Carl Jung, as I think he was uniquely insightful. On the other hand, I have serious reservations about some of his premises and assumptions. I would love to have an opportunity to wrestle with these in the comment thread!

Vote for Mumford ( without Sons )

My vote for Jung as a occultist

I have to admit I knew pretty much nothing about Wagner other than the obvious – so I’m really enjoying this series which is getting better and better.

My 5th Wednesday vote will also go to the Hitler as archetype topic.

Dear JMG

Your Alternative History; Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth domination of Eastern Europe, was a distinct possibility. From the Fifteenth through the early Eighteenth Centuries it was by no means certain which of the Kingdom of Sweden, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, or the age and Duchy of Muscovy would be the great power of Eastern Europe. The outcome was not at all predefined. For completeness, should probably include the Kingdom of Prussia in the mix too.

Finally, so many interesting topics, so few fifth Wednesdays!

Cugel

Regarding warbands and Prigozhin, trying to follow what’s happening in the eastern European theater became a lot more grey and bureaucratic without the colourful antics of the Chef and his army of redemption-or-death convicts. I can’t think of anyone else on either side that had that effect.

Voting Hitler 2024

Glory and honor are incentives. You can get men to do things for glory and honor. Other side of that coin, if there’s no glory or honor to be found, it can be awfully hard to motivate men to do much.

Now, if someone came along and was somehow able to offer glory and honor where there was none before…

>you make feudalism sound mighty appealing

It says something about how miserable this age has become that feudalism starts to look attractive. I’m not a big fan of the system, mainly because like with Communism, it doesn’t scale very well. It scales better than Communism does (almost everything scales better than that) but there comes a limit where that web of personal relationships starts looking like corruption and nepotism and then the whole thing wants to collapse from all the idiocy riddled within. Also see: French Revolution.

It’s also the default you get when all the other forms of political organizing have gone, it’s what you get when everything else has collapsed.

Hi JMG and everyone,

I’m enjoying this series of posts immensely.

What I’ll say, is, that so far, none of the characters come across as ‘moral’ or ‘the good guy ‘ so to speak.

Fascinating, definitely but not ‘endearing’.

Which is I suppose the point, if you look at them as symbols.

No Aragorn among them!

What teasers those 3 girls are! But then rivers are beautiful, but treacherous…

I would say Loge is my favourite character in this chapter, tricky, but kind of honest as well. He seems to understand all perspectives, but doesn’t really take anyones side.

He was treated poorly in the past, just by being who he was, so maybe that’s why he doesn’t really commit himself.

I’ve also been reading a bit more Schopenhauer, poor man, he really was gloomy wasn’t he? 😉

So, is the will, the instinct?

Is the guilt (original sin) he talks about, when man instinctively has a desire to reproduce, but knows that by doing so he is bringing into the world another person, even though he knows life is a trial and a tragedy (my words)?

In the same way that he was born into life, and that everyone is?

Forever repeating the same ‘sin’ in an endless cycle?

Am I near the mark at all?

My vote is for the Austrian.

To once again plug the book, The dark side of Camelot (read it, peeps), I’d like to see a future discussion about that book if we can get enough people to read it.

Would you recommend any of the other books by Sy Hersh?

I do have a book by Gore Vidal, mentioned last week.

I’ve had it for many years, The United States: Essays 1952-1992.

It’s very thick. Maybe one day. So many books, so little time! 😁

How many books (roughly) would you read in a month, JMG?

And anyone else that knows.

I don’t, not many, but I do try to read every night.

Regards,

Helen in Oz

@ Chris at Fernglade: I’m sorry to hear about your professional troubles. Nobody says, “It’s just business” when they do something generous or honest, do they?

It makes me think about my farming grandparents, and their insistence on sticking to their word. I’d thought it was a result of living in a very, very small town where your reputation was for life, but I’m wondering if it’s more about working with Nature. You can’t lie to Nature.

Meh. I guess I’ll vote for Literally Hitler(tm). And why everyone they don’t like becomes him, whether or not it makes any sense to shoehorn the person into that form.

These days, I hold Hitler, Biden, Harris, Putin, Trump as equals. They’re all politicians, whose job is to tell you what you want to hear. That’s all any competent politician does. Blah blah blah blah blah. Nobody ever asks why so many people of Germany wanted to hear what he had to say.

>Because reading the libretto, I was repeatedly & forcibly reminded of the One Ring in the Hobbit & LOTR

That’s amusing, because Tolkien denied copying anything from Wagner’s work. Something like “the only thing they have in common is a ring”?

Meanwhile some unknown Mexican cartel leader is in the process of inspiring the next LOTR in the year 3500.

Cugel, those are winged hussars and not pancerni, who usually wore chainmail and bore spears, unlike the hussars who bore lances(and a sabre and two pistols and wierd stabbing sword). If anyone is wondering why the winged hussars are without wings it’s because they were rarely worn in the battle and polish name doesn’t even mention wings(the name for the entire formation is husaria and for individual mebers it’s husarz, the hungarian kind are called here huzarzy singular huzar)

Now my question for our host, how hard our neighbours would have to drop the ball for the commonwealth to take over the region?

i vote for hitler(man that’s sounds bad)

Excellent piece, JMG, and I would like to add in a vote for Hitler as archetype.

Somewhat off-topic, so forgive me, but readers might be interested in a debate that has broken out over on Substack regarding James Lindsay’s latest paranoid ramblings – it seems that Trump invoked St Michael recently, which clearly means he’s a gnostic woke communist because Rudolf Steiner also invoke St Michael and Steiner was a member of the Theosophical Society which is clearly the root of all evil, blah blah blah:

https://substack.com/@flintandsteel/note/c-70963942

About the climate in Northern Germany there needs to be remembered that climate isn’t static; there are warmer and colder decades and centuries. In thed 1940s and 1950s, the climate in Middle Europe was indeed markedly colder than now; the inhabitants of Eastern Prussia did flee from the Soviet troops across the frozen-solid Baltic Sea in winter 1944, whereas noadays, there are scarcely a few days or weeks when there is any snow at all in winter, essentially, only in January and February, and temperatures seldom drop below -5 °C / 23 °F. This is probably, among other things, due to emission-driven climate change.

For a fifth Wedenesday subject, I vote, too, for the obsession with Hitler, since it seems to be an important factor i the obsession of the current elites about Donald Trump on the one side and the perception of the conflagration in the Levante, on the other side..

I forgot to add, that the latitudes, which Germany spans, are more or less the same as the latitudes of the Eastern Siberian island of Sakhalin.

Hi John Michael,

You may have missed this, but err, what would the Nibelung’s possibly say? Russia has captured Vuhledar after two years of Ukrainian resistance. How significant is the capture?

Interesting times indeed.

Cheers

Chris

Before I read this, it didn’t entirely occur to me that the reason modern life is so thoroughly characterized by alienation is because human social relationships are now mostly economic rather than personal, and the basis for all decisions that are made by people with power is mostly economic rather than human. It is certainly possible to think that this is natural and normal during the good times when money is flowing everywhere like beer at a bachelor party, but when the system starts creaking, popping, and sputtering the way it has been since 1976, and especially since 2006, the whole thing becomes very embittering for those who are not insiders of the system.

The other side of that coin, though, is that I really don’t think the scientific progress that has made human life a lot easier to manage in some pretty significant ways would have been possible had the feudal system of the Middle Ages remained in place. But to really benefit from this knowledge, I think it’s pretty clear that we need to come up with a system that is a lot more sustainable, adaptable, and resilient than the one we have right now that is currently falling apart on account of the lack of these qualities.

Thank you for this historical and natural perspective on the forces that caused Europe to turn out the way it did. Now I can feel some sympathy.

About Aberich renoucing love after being cockteased by the Rhinemaidens and the one-sided love relationship between Man and Nature. Nature is a harsh mistress that does not really care about her lover. Some appeasement can be achieved by dealing with her masters, the gods/daemons/orishas/kami but they themselves don’t care or can’t care that much about Man. They do care more then Nature, at least. Sacrifices works, astrology works, dreams and prophecies work.

But in the end it is perfectly understandable that at the first opportunity Man chained Nature and put a gag on her mouth and made her his slave. He suffered for too long under her thumb;

Helen wrote: ” Would you recommend any of the other books by Sy Hersh?” There’s his “The Samson Option” about Israel’s nuclear weapons program. It could prove to be quite timely just now. And, JFK comes across more favorably in it than in the other book.

I think Trump is the first presidential candidate who specifically talked about Mary. Past presidential candidates while they did focus on Jesus had a very Protestant avoidance of all things Mary.

Katylina #82:

Thank you for that. I had not heard they did not wear the wings in battle; although I have heard the reason for them was unknown. I assumed it was along the same line of: we are the best on this field, and we are charging you!

Thanks again,

Cugel

@Emmanuel Goldstein: Some esoteric Nazis thought Hitler was an avatar of Vishnu. Savitri Devi is the person you want to look up if you want to find out more. It’s a strange world, but I don’t get the obsession with this mustachioed man.

—

Note, if I could change my vote to not have the mustachioed man as a topic I will align with the Jungian Occultist bloc.

@JMG,

Good point on the parallel in Greece/Persia and Christendom/Ottoman Empire.

I wonder, did the Romans in their decadent era ever memory-hole Marthon and Salamis the way we have Vienna and Oranto?

Those stories are a bit awkward to everyone in the Modern West. On the one hand, you have a narrative of Europeans as being the only people on Earth capable of true agency– that is, only the Euros can chose evil, and everyone else’s actions are somehow a European’s fault. That Narrative obviously has to ignore the too-swarthy Ottomans. (Along with much else.) At the same time, the older, whiggish narrative needs to ignore the Ottomans because the idea that any force could ever have given Secular, Scientific Europe a run for its money just doesn’t fit. That the Ottomans were bested by a bunch of Catholic zealots only makes it worse.

My 5th Wednesday vote goes to Jung and occultism.

Another highlighted prayer addition– it seems important:

May Leonardo Johann from Bremen in Germany, who was

born prematurely two months early, come home safe and sound.

________

Re: the previously posted Helene prayer, it’s been revised as the prior wording was (due to my own hastiness) too SC-centric. The new form is:

RandomActsOfKarmaSC in South Carolina has been affected by recent hurricane devastation; may all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricane Helene be blessed, comforted, and healed.

“he had one of the few egos of the age as insanely overinflated as Richard Wagner’s. Yes, we’re talking about George Bernard Shaw, playwright, essayist, literary critic, insufferable intellectual snob, and crazed Wagner fan.”

Well, this reference to G.B. Shaw reminds me a British film in which GBS and his friend Sydney Cockerell have a long time friendship with a woman…a nun! Do you have seen it?

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109245/mediaviewer/rm3808780033/?ref_=tt_mi_0_2

Kyle #23 said:” I vote for whichever topic has the highest number of votes and is NOT about Hitler.”

I agree too.

I’d like to cast my vote for the obsession with Hitler.

“Taylor, ah, but the Romantics believed that the world created by Alberich’s lovelessness could be overthrown and replaced by a world based on love. It never occurred to them that their ideologies were just as loveless as the ones they hated. We’ll get to that…”

At some point the human capacity for self deception probably should have stopped surprising me nearly as much as it does….

Michael the Archangel or literally Michael the Top Angel got some press recently from being invoked by Trump. My vote is for talking about him and the role of angels. I do think Michael is on the move. Have had a few angelic encounters. My sense of them were what an angel told John in Revelation – “I am a fellow servant with you and with your brothers and sisters” and in Hebrews “are not all angels ministering spirits” though there are some bad boys out there who fall into a different category.

Ooops! JMG, excuse me. I’ll vote in positive. Mi vote is for L. Mumford!

@Chris #86 Since you bring it up, I feel obliged to note that the name Vuhledar/Ugledar means nothing less than the Gift of Coal. (Donbas, the region it is in, is itself short for the Donets Coal Basin.)

Re: #51 “It is because the demythologization of that war [WWII] would be the final nail in the coffin of the moral legitimacy of the PMC.”

The PMC and its central planning had a lot to do with winning the war. Rationing, price controls, and an industrial plan diverted resources into war production that the Axis simply couldn’t match. As Stalin said, “Quantity has a quality all its own.” And the T-34 was a pretty decent tank. The PMC would love to return to those glory days when they were all powerful and assumed to be all-knowing.

And down at #56, why do so many people find socialism appealing? I’m somewhat mystified myself. To some extent it seems to be fear related, they want a safety net. Despite history they think that this time the government won’t shoot them in the back. This time there will be no gulags. Even if they are in a work camp that’s three hots and a cot, right?

Another thought is that people don’t do well with randomness. Socialism is all about plans and schedules. Everything is dictated by some elite. No thought required or tolerated for that matter. See John Kerry’s rant about free speech being the enemy of democracy (at least of his flavor).

@Adara9 – Or the one about the old British lady watching Cleopatra and saying, smugly, “How very different from the home life of our own dear Queen.”

Oh, yes, in the S/f fandom community there were jokes about “I’m singing Frodo in “The Ring Cycle”” and similar speculations based on later historical mixups in the popular mind. Star’s Reach contained a lovely example in Trey’s imagining Dizzy Gillespie singing his way, holding out his hat for coins, back to Ithaca NY after the Trojan War.

@Goldenhawk #37 – yes, indeed. In British history, you could see the dividing line at Bosworth Field, when the last King of England to operate under the old system of personal ties and loyalties was “this day slain and murdered,” and replaced by a cold-blooded miser for whom treachery was a tool of state.

@Aldarion #40 – in the heroic age epics, love was the bond between warrior-brothers.

Luke Dodson @ 83. I will believe in a Trump conversion when I see him openly attending Mass. The Republicans cannot win elections in many if not most jurisdictions without conservative Catholic voters. Those voters were promised an end to Roe vs. Wade which, they have not failed to note, was accomplished only after 40 years. Until I see evidence otherwise, I will suppose that incidents like the invocation of the Archangel are mere dog whistles.

Hi JMG and friends,

One thing which stuck out to me from this post was the mention of “waterwheel” industry and this sort of mill-based hydropower powering the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. To me this sort of small scale hydropower sounds like a much more sustainable base for a manufacturing economy than coal, and far more so than other forms of fossil power or green energy which depends on the manufacture of solar panels or the like. I feel that this sort of setup, with mills dotting the landscape of places like where Appalachia gives way to the coastal plains, could be what American manufacturing will look like after the end of our current phase of industrial civilization.

In truth the mention of the Rhinemaidens here and the importance of the Rhine in Wagner’s work makes me feel like we Americans are neglecting our own “Mississippi-maidens”, “San Joaquin-maidens,” etc. Perhaps it’s natural in an age of roads and planes, but America’s rivers have been critical for transportation. Perhaps in the future this relevance will return. (Maybe it hasn’t really gone away; there’s a documentary by Vice floating around on YouTube about the critical nature of the lock and dam system on the Mississippi when it comes to shipping, and how like other aspects of American infrastructure it’s dangerously close to collapse).

Finally, I wanted to share this article about how a community in North Carolina responded to the loss of most features of modern life (power, Internet, etc.) in the wake of Hurricane Helene: https://www.ncrabbithole.com/p/the-town-meeting-black-mountain-nc-hurricane-helene . What I found interesting was how people organically returned to a sort of pre-industrial system, with a heavy reliance on “town criers”, paper communication, etc. (Of course, not all was lost, and things like radio communication were also essential in helping people find loved ones and the like). But I think one thing that surprised me is how calm the community described in the article was. Things didn’t collapse into anarchy even with a massive natural disaster and the loss of modern essentials (forget about any looting, there wasn’t even any heckling at community meetings!). Indeed, people seemed to coalesce around the town’s police department and sort of built up a rudimentary infrastructure around it to handle the crisis. I can see certain elements of American government on all scales providing such a scaffolding for post-industrial Americans as they build their new world. Perhaps the long collapse will not be as gruesome a process as many fear.

On the note of a reader-selected monthly post, then, I vote for a post about what elements of America today (infrastructure, geography, culture, etc.) will survive the industrial age and which could serve as the foundations of the next American civilization.

People here talking about America ignoring the 250th anniversary reminded me that back diring the covid lockdowns I was ordering books from the libraries all over on Revolutionary War uniforms so that I could design a modern honorary version, and I got ice and a few side eyes from the library staff. This was well before I checked out Jordan Peterson or Alex Jones which led to them suddenly hassling me (it’s not over).

While I’m also voting to understand the obsession with Hitler, I also am extremely curious about our shame and self hate. When I was a victimmy liberal copycat I’d trash talk America about our imperialism but I existed as an outsider. I didn’t want to be the prevailing voice. I wanted a higher standard without the hypocrisy.

I don’t understand the current prevailing mindset that seeks to fix by eradicating but has no alternative ideas. Just shallow tantrums. They’ve approached fixes like that with sexism racism and all isms.

A lot of us …”rougher ” types started sympathizing with the cops once it became a thing for the normals to trash the cops. I remembered talking to some guys on the street about how the normals got it aaaall wrong and you needed not to abolish law and order but to try and fix it. Once law and all order is gone you’ve got what we have in san francisco. Theft is constant and it’s demoralizing for all.

Erika

(Oops another Annette here.)