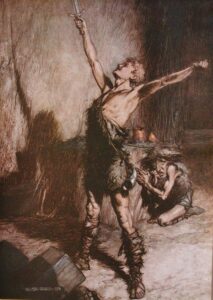

Siegfried’s betrayal of his ideals and his love for Brunnhilde, the central theme of our discussion three weeks ago, is also the hinge upon which the entire story of The Ring turns toward its end. Our blond and brawny hero was doomed the moment he took the Ring from Fafner’s hoard, Alberich’s curse guarantees that, but it was not yet certain how the curse would destroy him. Once Siegfried put his fearlessness and his magic cap in the service of Gunther’s sleazy plan, that was settled, and the rest of the story proceeds with terrible inevitability from that point on.

Of course, outside the world of the story, that outcome was determined before Richard Wagner was born. The Twilight of the Gods depends more than the cycle’s other operas on the raw material Wagner inherited from medieval legends. It’s hardwired into the tale that Siegfried would fall in love with Gutrune, that he would pay her bride-price by using the magic cap to obtain Brunnhilde for Gunther under false pretenses, that Brunnhilde would discover the ruse and repay one betrayal with another by letting Hagen know about Siegfried’s only vulnerable spot, that Hagen will follow through by thrusting a spear through Siegfried’s back when the hero expected no danger, and that the consequences of that treacherous deed would include the deaths of Brunnhilde, Gunther, and Hagen, and the fall of the Gibichung kingdom.

All those details of the plot came to Wagner down through the centuries, all the way from whichever forgotten storyteller in the Dark Ages first wove together the story of fall of Gundacar the Gibichung, the last king of the Burgundians, with the tale of the vengeful Frankish queen Brunechildis and the archaic myth of the sun-hero who slew the dragon of winter and freed the golden sun. It’s what Wagner did with those elements, and how he used them as a basis for talking about the political, economic, and philosophical themes that structure the entire story of The Ring, that shows Wagner’s genius.

I don’t simply mean that last word only in an artistic sense, though of course Wagner was a brilliant creator. He wrote at a time when the literary genre of allegory hadn’t quite become moribund yet, and it was still just possible to express profound thought in the form of symbolic narrative. Here as in so many other ways, he stood at the hinge of ages, when one era was ending and another about to begin; it’s no surprise that so many people nowadays have trouble grasping the idea that a great work of art can also deal with the gritty realities of politics and economics. Friedrich Nietzsche, by turns Wagner’s best friend and bitterest enemy, attempted the same thing with philosophy a few decades later in the mythic narrative of Thus Spake Zarathustra, but by then it was already too late. Next to nobody understood what Nietzsche was saying, and his own plunge into insanity and death followed not long thereafter.

Wagner avoided that fate, barely. Schopenhauer’s philosophy gave him a way to make sense of the tragic conclusion of his story, and thus also of the equally tragic conclusion he foresaw for the entire historical arc of European society. On a more pragmatic level, the ample financial support he received from King Ludwig II of Bavaria spared him a great deal of stress, and the emotional support he received from his second wife Cosima—not to mention her patient and competent management of his affairs, in several senses of that word—took care of much of the rest. Where Nietzche ended his life as a burnt-out psychotic in a mental ward, Wagner ended his as the Western world’s most adored living composer, living in luxury and basking in the applause of legions of crazed fans in every country of Europe and the European diaspora. How many of those fans understood what he was trying to say is a good question, and one that haunted him in his last years, if Cosima’s recollections are anything to go by.

We can try to make sense of the implications of his ideas by paying attention to some of the core themes of The Twilight of the Gods, and relating them to the subtext we’ve been following all through this series of posts.

Let’s start with one detail that often gets missed: the way that some of the most important symbols and dramatic actions in the earlier operas in the cycle get reprised in this one. The most striking of these, appropriately enough, center on the Ring itself. Just as Wotan takes the Ring by force from Alberich, setting the entire tragedy of the later operas in motion, the old god’s grandson Siegfried takes the Ring from Brunnhilde by force, setting his own personal tragedy in motion. Just as Wotan, motivated by greed, refuses to give the Ring back to the Rhinemaidens when he has the chance, his grandson, motivated by pride, refuses to give the Ring back to the Rhinemaidens when he has the chance—and doom clamps down hard on both characters once that final chance has slipped away.

Notice also how Wotan in the aftermath of The Rhinegold redirects his affections from Fricka to Erda, furthermore, and thus guarantees that Fricka will turn on him with icy fury in The Valkyrie and destroy his plan to regain the ring. In much the same way, Siegfried in the first act of The Twilight of the Gods redirects his affections from Brunnhilde to Gutrune, and thus guarantees that Brunnhilde will turn on him with equally icy fury, and even more devastating effect, in the second act. In all these ways and others, Siegfried shows himself to be Wotan’s rightful heir, as selfish and self-defeating as the king of the gods himself.

Siegfried isn’t the only character to reprise an earlier role in the present opera, of course. Just as Sieglinde was kidnapped and forced into marriage with Hunding in the backstory of The Valkyrie, Brunnhilde is kidnapped and forced into marriage with Gunther in The Twilight of the Gods. It’s a bitterly edged irony that Sieglinde’s own son is the one who does the kidnapping in this latter case, just as it was Sieglinde’s own father Wotan who arranged for the kidnapping in the earlier case. Yet there’s an important difference here, as in the other parallels just mentioned. Wotan knew exactly what he was doing when he treated his mortal children as pawns in his plot to recapture the Ring. Siegfried, by contrast, has no clue what’s going on. He stumbles blindly along a track laid down before he was born by the events of the first two operas. It’s for this reason that Brunnhilde can rise above her own bitterness and forgive him in the tremendous final scene of the opera, just before she sacrifices herself and her world to the consuming flames.

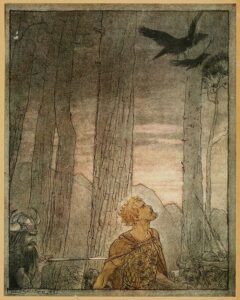

In a very real sense, then, the action of The Twilight of the Gods recapitulates the action of the whole cycle of operas. What was enacted then in a world of gods, giants, and magic dwarfs is reenacted in the human world. The great difference between this last opera and the three that come before it, after all, is that now the world of gods and mythic beings has receded almost beyond the range of vision. The Norns appear in the first part of the Prelude, but the cord of destiny snaps in their hands and they vanish from the scene; one of the Valkyries puts in an appearance, pleading with Brunnhilde to return the Ring to the Rhinemaidens, but without effect; Alberich comes to his son Hagen in the depths of the night, but as an insubstantial presence, almost a ghost; and Wotan and his castle in the clouds hover like a phantom in the distance, visible only in the final scene when the flames take them.

There’s an ancient vision of history underlying all this, and it’s one that Wagner—like every other person who received a middle or upper class education in nineteenth-century Europe—learned about in childhood. The Roman polymath Marcus Terentius Varro, whom other scholars of his time considered the most learned of all Rome’s antiquarians, divided history into three ages: the age of gods, which is chronicled only in myth; the age of heroes, which is chronicled in legend; and the age of men, which is chronicled in history. That’s the scheme that structures the temporal vision of The Ring. The Rhinegold is set in the age of gods, and human beings play no role in it at all. The Valkyrie and Siegfried are set in the age of heroes, and in it human beings mingle with gods, dragons, and other legendary beings. The Twilight of the Gods is set in the age of men, when the gods are fading shadows that perish in the final scene.

It’s an indication of the importance of that scheme that JRR Tolkien, whose Ring trilogy so often provides an edgy counterpoint to Wagner’s tetralogy, also used a variant of Varro’s system. No, these aren’t the three ages of Middle-earth. If you happen to read The Silmarillion, Tolkien’s account of the myths and legends of the elves, you’ll find that there were ages before the beginning of the notional First Age. For example, Morgoth was bound for three ages of the world in the prison of Mandos after his defeat at the siege of Utumno.

These three ages were the Noontide of Valinor, Tolkien tells us, and correspond to the age of gods in Varro’s system. There followed the three ages of Middle-earth, during which Elves and Men contended with Morgoth and his servant Sauron; these correspond to Varro’s age of heroes. Finally, Tolkien speaks of the Fourth Age, which he and Varro both term the age of men. The idea that the world would last for seven ages was a staple of medieval Christian legend, and Tolkien blended it with Varro’s scheme with his usual panache. But then Tolkien was a Christian, of course, and Wagner was not—a point which will become even more edged when we reach Wagner’s final opera Parsifal.

The same system of three ages also has a distinctive meaning in the light of Wagner’s great metaphor, shaped as it was by Feuerbach’s interpretation of myth and legend. To Wagner, who didn’t believe in the real existence of gods, myth was necessarily what Feuerbach said it was, a way of talking about the highest ideals and basic understandings of a particular human society. That was why The Rhinegold, set in the age of gods, laid out what Wagner identified as the fundamental problem of European society: the commodification of nature (very much including human nature), the process by which all values were reduced to monetary value and thus controlled by those who had money.

The age of heroes is transitional, representing the way this fundamental problem worked out in history. At this stage of the metaphor, gods and humans, ideal principles and actual historical phenomena, mingle and interbreed with very mixed results. In The Valkyrie and Siegfried, Wotan—in the earlier opera, the ideal principle of rule by an intellectual elite, the grand and disastrously misguided dream of Pythagoras, Plato, and their myriad followers down through the ages—became the intelligentsia as a historical class, the people who embraced the ideal principle and tried to make it real in the world of history.

We watched them place all their hopes on the idea of liberty, and manipulate that idea in the hope that they could use it to seize power. We also saw them lose control of it, as the ideal was taken from them by the revolutionary Siegfrieds of radical movements in Europe and around the world, who overthrew the authotiry of the intellectuals as their first act, replacing it with the rule of raw force in the normal revolutionary manner. Opera being opera, and myth being myth, that took place one time only. In history, of course, it repeats over and over again. So far, at least, each new generation of would-be Wotans has to learn the same lesson the hard way.

That’s the basic theme of The Twilight of the Gods. Having taken the concept of liberty far more literally than the intelligentsia intended, each generation of revolutionary Siegfrieds liberate themselves from the ideologies and belief systems that were intended to make them hand over power to the intelligentsia, and proceed to bargain with the old elite classes for whatever Gutrune-shaped goodies they think they can get. The Gunthers and Hagens of each generation, in turn, are generally more than ready to cut a deal with the Siegfrieds, partly because most of them were Siegfrieds in an earlier decade before they sold out, and partly because Hagen’s spear is always handy if the Siegfrieds step out of line. Those of my readers who have watched the history of the last half century or so know this song well enough to sing it in the shower.

It would be easy enough to portray this as a straightforward repeating cycle. There’s a broader pattern at work in it, however, and it’s one that many people are beginning to notice around them at this phase of our own historical process. Each repetition of the cycle, after all, whittles away at the legitimacy of the system and also of the ideals that it supposedly embodies. Each generation of revolutionaries, as it abandons the rhetoric of liberty in order to secure its own privilege, makes it harder for anyone to take seriously the claims of the new leadership regarding liberty—or anything else, for that matter.

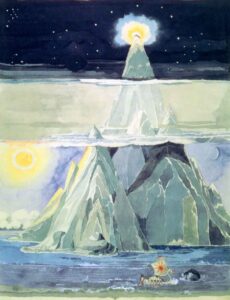

It’s hard to tell, either from the operas or from Wagner’s letters and essays, whether he expected the loss of faith in the Valhalla of Western ideals to be gradual, or whether he foresaw a collapse as sudden as the one that happens in the last scene of The Twilight of the Gods. It’s clear, though, that he recognized that an ideal betrayed often enough loses any power to move people to action. Thus it’s not just the kingdom of the Gibichungs that goes up in flames, it’s Valhalla itself, and also Brunnhilde, the ideal of liberty, who kindles the fire in which she herself will perish.

That, in turn, is when the Rhine comes rushing in to finish the process.

All through the cycle of operas, from the opening chord of The Rhinegold, the waters of the Rhine have symbolized nature. In that first opera, nature had a wholly passive role to play: the Rhinemaidens’ guardianship of the magic gold didn’t give Alberich the least trouble once he decided to take it. When Erda the earth goddess put in her appearance toward the end of The Rhinegold, all she could do was offer good advice, and she was receptive enough to Wotan’s response that nine Valkyries promptly resulted. In the next two plays, the role of nature was nearly as passive: in The Valkyrie, the ash tree growing in the middle of Hunding’s hall didn’t offer the least resistance when Siegmund extracted the sword from it, and while the forest bird in Siegfried had a slightly more active part to play, her role was simply to give the clueless hero some idea of what was going on.

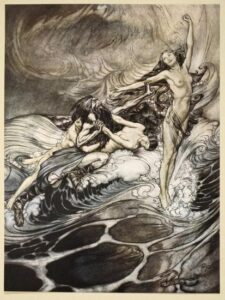

Yet that passivity comes to a decisive end in The Twilight of the Gods. The Rhimemaidens fail to convince Siegfried to hand over the Ring, true, but they make the attempt; they have much more success explaining to Brunnhilde everything she doesn’t know about the situation; and when flames rise from Siegfried’s funeral pyre and Brunnhilde flings herself into the fire to join him in death, the waters of the Rhine come sweeping in to take the Ring from Siegfried’s ashes and return it to where it belongs. When Hagen tries to intervene and get the Ring for himself, the Rhinemaidens show that they’ve learned from their experiences. They don’t tease and taunt him as they did his father; they drag him under the waters and hold him there until he drowns.

So the story ends. In terms of Wagner’s great metaphor, what has happened? Simply this: in the final crisis of society, the system of commodification itself breaks down. Money, that complex system of tokens that the elites of industrial society use to control and exploit the exchange of goods and services, turns out to be too brittle a thing to survive the final crisis of the society that created it. As the system burns down, all the tokens of notional wealth—including, by the way, gold, the keystone of the financial system in Wagner’s time—lose their ability to exert power on people and extract real, nonfinancial wealth from them. Those glittering objects, once rings of genuine power, become nothing more than pretty toys for Rhinemaidens to play with.

That, at least, was Wagner’s vision. One of the fascinating things about it is that history appears to agree with him. It’s one of curious details of economic history that as the Roman empire fell and the Dark Ages closed in, money dropped almost entirely out of use in economies across the Western world. In 300 AD, nearly every imaginable transaction in what was then the western half of a huge empire involved the exchange of gold, silver, or copper coins; five hundred years later, the great majority of people in the same region could easily go through their entire lives without ever handling a coin. Market economies went away almost completely, and were replaced by customary systems of exchange in which a man might pay rent on a piece of land by handing over a tenth of the grain he grew on it each year, plus two piglets suitable for roasting each Christmas. Commodification collapsed, giving way to the same patterns of personal relationship that the young Wagner and his fellow romantic revolutionaries had glorified so enthusiastically.

Yet The Twilight of the Gods has very little else in common with the fond fantasies of redemption through revolution that Feuerbach and the left-Hegelians had put into circulation. Just to start with, Wotan and Valhalla are gone; the intelligentsia and its castle in the clouds are among the casualties of the process. The Gibichung kingdom is right next to them on the obituary page, and so are death notices for nearly all the characters. (Not, however, Gutrune. Keep her in mind; we won’t see her again, but she’s a bridge to the final stage of our discussion.) To get out from under the curse of commodification, Wagner seems to be saying, the only option is to burn everything down to the ground

It’s a bleak prospect. Wagner being Wagner, he couldn’t leave it at that. He had only one more opera to write after The Twilight of the Gods, and he considered it his most important work—so important, in fact, that while he lived it could only be performed at his own specially constructed opera house at Bayreuth. This was Parsifal, the opera in which he tried to come to a final synthesis and resolution of the themes he’d introduced in The Nibelung’s Ring. In order to make sense of that, we’re going to have to take another deep dive into the world of myth and legend…and when we do, starting two weeks from now, we’ll find that Wagner has gotten there before us and is waiting to show us around.

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Karen who is in the hospital with RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus) quickly recover and be restored to full health.

May Other Dave’s father Michael Orwig, who has been in the hospital since 1/20 with almost complete liver failure and 20% kidney function, have found the strength to survive and thrive when he recently came off of his respirator, and may he be blessed with robust healing that allows him to regenerate his failing organs to the fullest extent that the universe allows; may his wife Allyn and the rest of his family be blessed and supported in this difficult time.

May Jennifer, who is now 36+ weeks into pregnancy with the baby still in breech position, have a safe and healthy pregnancy, may the delivery go smoothly, and may her baby be born healthy and blessed.

May Kevin’s sister Cynthia be cured of the hallucinations and delusions that have afflicted her, and freed from emotional distress. May she be safely healed of the physical condition that has provoked her emotions; and may she be healed of the spiritual condition that brings her to be so unsettled by it. May she come to feel calm and secure in her physical body, regardless of its level of health.

May Viktoria have a safe and healthy pregnancy, and may the baby be born safe, healthy and blessed. May Marko have the strength, wisdom and balance to face the challenges set before him. (picture)

May Linda from the Quest Bookshop of the Theosophical Society, who has developed a turbo cancer, be blessed and have a speedy and full recovery from cancer.

May Matt, who is currently struggling with MS related fatigue, be blessed and healed such that he returns to full energy; and may he be enlightened as to the best way to manage his own situation to best bring about this healing.

May NPM/Nick’s 12-year-old Greyhound Vera, who passed away on 1/20, be blessed and comforted, and granted rest and a peaceful transition to the next life. (1/23)

May Frank R. Hartman, who lost his house in the Altadena fire, and all who have been affected by the larger conflagration be blessed and healed.

May MethylEthyl, who recently fractured a rib coughing, heal without complications, and have sufficient help for the move that she and hers are making at the end of the month.

May Sub’s Wife’s major surgery last week have gone smoothly and successfully, and may she recover with ease back to full health.

May David/Trubrujah’s 5 year old nephew Jayce, who is back home after chemotherapy for his leukemia, be healed quickly and fully, and may he, and mother Amanda, and their family find be aided with physical, mental, and emotional strength while they deal with this new life altering situation. (good news update!)

May Mindwinds’s dad Clem, who in the midst of a struggle back to normal after a head injury has been told he shows signs of congestive heart failure, be blessed, healed, and encouraged.

May Corey Benton, who is currently in hospital and whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer. He is not doing well, and consents to any kind of distance healing offered. [Note: Healing Hands should be fine, but if offering energy work which could potentially conflict with another, please first leave a note in comments or write to randomactsofkarmasc to double check that it’s safe] (1/7)

May Christian’s cervical spine surgery on 1/14 have been successful, and may he heal completely and with speed; and may the bad feelings and headaches plaguing him be lifted.

May Open Space’s friend’s mother

Judith be blessed and healed for a complete recovery from cancer.

May Bill Rice (Will1000) in southern California, who suffered a painful back injury, be blessed and healed, and may he quickly recover full health and movement.

May Peter Van Erp’s friend Kate Bowden’s husband Russ Hobson and his family be enveloped with love as he follows his path forward with the glioblastoma (brain cancer) which has afflicted him.

May Daedalus/ARS receive guidance and finish his kundalini awakening, and overcome the neurological and qi and blood circulation problems that have kept him largely immobilised for several years; may the path toward achieving his life’s work be cleared of obstacles.

May baby Gigi, continue to gain weight and strength, and continue to heal from a possible medication overdose which her mother Elena received during pregnancy, and may Elena be blessed and healed from the continuing random tremors which ensued; may Gigi’s big brother Francis continue to be in excellent health and be blessed.

May Scotlyn’s friend Fiona, who has been in hospital since early October with what is a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, be blessed and healed, and encouraged in ways that help her to maintain a positive mental and spiritual outlook.

May Peter Evans in California, who has been diagnosed with colon cancer, be completely healed with ease, and make a rapid and total recovery.

May Jennifer and Josiah, their daughter Joanna, and their unborn daughter be protected from all harmful and malicious influences, and may any connection to malign entities or hostile thought forms or projections be broken and their influence banished.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

” an ideal betrayed often enough loses any power to move people to action”.

Yeah. Hit the nail on the head. We’re seeing a lot of that in real life in a lot of areas of late, and it’s a large part of why things are getting so unstable and generally interesting-timesy.

You should publish this series as a book

It is really fascinating in the lenses of our current environment in Globalized Western culture. Great read once again this serious really has me enthralled. Thank you.

The Ring Cycle so far reminds me of one of the meanings that I read from the Second Branch of the Mabinogion, right down to nature’s taking back what is her own at the end. Does that make sense to you? And if it does, does the Third Branch correspond in some sense to Parsifal?

interesting topic, I haven’t read Wagner, and I think that with your summaries I think that it is enough, the conclusion of “Twilight of the Gods”, I don’t know how Wagner came to that conclusion, but Giambattista Vico came to the same thing around the 18th century, although talking about Vico is complicated. I speak Spanish (Vico was Italian), believe me, reading Vico in a Latin language, despite being similar languages, it hurts anyone to read Vico.

Do you have any plans to do an analysis, similar to Wagner’s, of Nietzsche? It would be interesting although very long, but it would be nice to read something about Nietzsche from other perspectives, an author so forgotten today.

In other news, have you seen the recent declaration of the United States government (I’m from Latin America) to control and turn Gaza into a tourist resort (Gazysium? because of Elisyum the movie)? My reaction was to laugh 🤣 at first because, far from the pompous statements, in my opinion, this has been one of the great defeats for Israel, this is simply accepting the fact that they are incapable of administering their territory, Gaza is Israel’s as far as I understand, they leave the administration of Gaza to an external nation and the reconstruction is the responsibility of the UN, easy, without complications.

I took the time to reread this opera just before this post came up.

It’s a wonderful post, and I look forward to Persifal.

Best regards,

Marko

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Pygmycory, it’s one of the things that ideologists never understand, and just as routinely end up suffering some versions of Hagen’s fate as a result. We may see a lot of that in the near future.

Charles, I’m assembling it into a manuscript as I write it. I’ll have to see if anybody wants to publish it, though.

Kyle, you’re welcome and thank you!

SLClaire, in a certain sense, yes — the connections between the Mabinogi of Manawyddan ap Llyr and the Grail legends generally are worth noting. (The Waste Land motif is common to both, for example.) More broadly, though, the Grail legend in its full form corresponds to the four Branches in general; I may discuss that in a book someday.

Zarcayce, I’ve read Vico in English (there are several good translations) and checked the text against the Latin original; he’s hard to read unless you can get into the end-of-the-Renaissance headspace he inhabited, but he makes a lot of sense once you’re there. I hadn’t considered a series on Nietzsche, though I’ve written about him already. Here are two examples:

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.200605.xyz/2013/03/the-sound-of-gravediggers.html

https://thearchdruidreport-archive.200605.xyz/2013/05/the-rock-by-lake-silvaplana.html

With regard to the Gaza thing, keep in mind that this was an off-the-cuff comment by Donald Trump, who’s made a career of dropping bombs like that. Few of them ever go anywhere, because their goal is to destabilize the situation and keep his opponents off balance. We’ll see if there’s any attempt to follow through on it.

Marko, thanks for this.

JMG, it is a pity you don’t do video. I think you would enjoy Castle in the Sky. The artists of Studio Ghibli have created some of the most beautiful images of our day.

Thank you for the remark about Plato, Pythagoras, et al. There are those now who would like to reinvent Plato as some kind of enemy of oligarchy and defender of democracy. They did not read the same Plato I did.

So I gather the options for the USA in the coming months, years, and decades are:

1. The people back Spenglerian Ceasarism. The Ceasars use appeals to religion (probably divine right of kings) and tradition to maintain power instead of ideology. The people by-and-large lose interest in politics and ideology.

2. Social and cultural disingration from disillusionment. Selfish desires are the only things that seem real after ideology collapses, and society can no longer function. This seems to me to be what Wagner is describing.

3. Abandon Faustian excesses and fall back on different ideologies or rules of thumb that work better at this period of history. Seems like the approach favored by the commentariat is a Fortress America the Trump administration might bring about, plus recognition of resource limits and the need for America to live within its means.

I thought history could be neatly folded into the Aeon of Isis, Aeon of Osiris, and Aeon of Horus… or the time of matriarchy, patriarchy, and now youth-y-archy. Malarkey.

Also, Tolkien was really a Hegelian in disguise. What is the return of the Elves to Valinor but the ultimate unfolding of the “long now” into the ultimate paradise free from the worldly cares of middle earth? Aka communist utopia for elves.

Or maybe Wagner should have got in touch with Hari Seldon to mitigate the twilight of the intelligentsia?

Just kidding / late afternoon brain amusements to keep me from lashing out at the closest PMC representative / glad a coworker had their last day, hopefully they don’t hire a repeat / didn’t get enough sleep.

Once again, the Ring Cycle makes for some interesting comparisons to real life, and the fate of civilizations…An example… Season 1 of the Landman, Billy Bob Thornton, whose job is managing drilling and producing oil and gas in the Permian basin, has an interesting conversation with a drug Kingpin who has just rescued him from the violence of a lower level thug…The genial Kingpin says that we have to cooperate so we don’t interfere with each other, which is also used for smuggling…Billy Bob kind of agrees, but says neither of our businesses has much of a future, so you should diversify…Kingpin agrees, and says, your business still has some future left, so I want to get into it….For a cable series, the mutual acknowledgement that we will be in a totally different world not too far down the road, is startling….

“Thus it’s not just the kingdom of the Gibichungs that goes up in flames, it’s Valhalla itself, and also Brunnhilde, the ideal of liberty, who kindles the fire in which she herself will perish.”

This magnificent sentence sent chills up my spine.

Cataclysmic fire (comets, volcanoes) and flood cycles are clearly part of collective human memory, since the motifs recur in multiple myths and legends. There is even evidence of such events recorded in ancient architecture, according to some serious researchers.

Thank you for this series; I’m looking forward to the Parsifal installment.

Why is it that for Wagner true love is illegitimate or forbidden? Siegmund and Sieglinde are siblings, Brunnhilde is Siegfried’s aunt. Further afield are Tristan and Isolde (she’s promised to King Mark), Lohengrin and Elsa (he’s sworn to never give his name) and even Walther and Eva (who’s promised to the winner of the singing competition). For that matter, none of Wotan’s children are by his wife! Is this just a Romantic thing or does it play into the allegory?

Thank you again, JMG, so very interesting to me (and many others here) for this history of ideas through opera.

Double thank you for your essay on Jung from last week as well.

Look forward to the weeks ahead,

I second Zarcayce’s hope for more posts on Nietzsche–especially his relationship with Wagner, but also more of your interpretation of Also sprach Zarathustra.

Hi John Michael,

The unfolding events in the saga are hardly surprising. At any point in time, the protagonists could simply all walk away from their desire for power and control. Then they could all go off and do something more useful with the time and resources left to them. But do they do that?

The funny thing about power, is that Wotan – just for an example – doesn’t seem to comprehend that his own grubby stature limits the possibilities available to him, even if he got the cursed ring. He’d not be able to rise beyond his own self. In fact, it reflects very poorly upon his character that he even seeks power whilst being unable to wield it.

The protagonists are all themselves part of nature, though they realise it not, until nature sweeps them all away. Then they know.

I’m hardly surprised that in the early 70’s there are the earnest Limits to Growth studies. And in these more enlightened days, we have the WEFters. The world is probably a very baffling place for those folks.

Cheers

Chris

I’ve been waiting for the moment to ask about the role of Tolkien in the subversion of the ring myth. My great uncle who bombed Germany with the US Army Air Corps mentioned that the code phrase was always: “It’s not over till the fat lady sings.” I learned that this was a reference to Brunnhilde’s aria and immolation at the end of Twilight of the Gods. The strategic bombing mission had an objective to make the mythical end of Midgard come true by fulfilling the myth and burning Germany to the ground.

This is where Tolkien comes in, although I don’t think Dion Fortune actually mentions his work during the war at Oxford as part of the Magical Defence of Britain, it is said that he was tasked with taking the ring myth in a different direction than the German High Command would have wished. I’m told the idea was to toss the ring into the Crack of Doom rather than let it be returned to the Rhine. What do you make of this strategic self-fulfillment of prophecy and the British hijack of the ring myth to write an ending to the war?

Mary, I have a complicated relationship with Pythagoras and Plato. They really were the founders of the Western mind, the people who kickstarted the intellectual tradition that shapes my own thought from top to bottom; they were also wrong, catastrophically so, about the foundations of human thought and also about its proper political expressions. I try to reflect that in my discussions of them. It’s crucial to realize that they were the forefathers of that whole deluded notion that intellectuals ought to tell everyone else what to do — democracy was exactly what they opposed the most.

Patrick, yes, and we’ll get all three of those; the second has been pretty common up to this point and will doubtless continue to be widespread, the first is coming into vogue right now, and the third is further off but already stirring.

Edward Etc., amusements or not, Hari Seldon is a fine example of why the twilight of the intellectuals can’t be mitigated. There’s something profoundly tragic and relevant in that scene where his projected image is rabbiting on about what should have happened next, when the rise of the Mule has thrown his entire scheme of future history into an interplanetary dustbin. As for those Aeons, Crowley never did grasp that the Aeons aren’t sequential periods of time; as any Gnostic could have told him, they’re eternal spiritual powers who are all present and active at every moment of time. Sure, he proclaimed the word of one Aeon, but so does every other soul, since each of us is aligned with one or another Aeon and constantly proclaims it in all our thoughts, words, and actions.

Pyrrhus, fascinating. Things really are in motion!

Goldenhawk, thank you. Yeah, there’s good reason that destruction through fire and flood are so well represented in the world’s mythologies.

Roldy, it was a Romantic thing. Remember that marriage in Wagner’s time was a tangled mess of cultural expectations that guaranteed misery for most of its inmates; remember also that the segregation of the sexes at that time meant that almost always, the first person anybody ever had the hots for was a close relative. (Paging Dr. Freud…)

H4nksh4w, you’re most welcome and thank you.

Ambrose, oog. I’ll consider it — I’ve got a copy in my library, of course — but it would be a serious slog.

Chris, ding! We have a winner. Stay tuned…

Malleus M, er, you do know that Tolkien’s trilogy was unknown to anybody but his closest friends until shortly before the publication of the first volume in 1954, don’t you? Yes, the business about the fat lady’s vocal talents was about Brunnhilde, but it’s a reference to the fact that The Twilight of the Gods is a very, very long opera, and people who weren’t crazed Wagner fans had to be reminded that until the soprano who played Brunnhilde belted out that final piece, they still had more to sit through!

“It is said,” by the way, is shorthand in the occult community for “crap I made up;” there’s no evidence at all that Tolkien was involved in any magical working, much less that he (a devout and very conservative Catholic) had anything to do with Dion Fortune’s magical defense of Britain; his idea of what to do for his country involved spending a lot of time on his knees praying the rosary. You’re right that he deliberately had his Ring thrown into the fire as a smack at Wagner, whose work he hated — Wagner was way over on the left, Tolkien way over on the right — but the Nazi government banned performances of The Twilight of the Gods during the war, because the last thing they wanted was to see that enacted in real time — as of course it was.

Say, did you ever notice the similaries between Delville’s Parsifal and Hawkwind’s Space Ritual album cover? (The uninitiated and Wagner-saturated might give the track, “Orgone Accumulator” a little ear time.) My sources tell me that the Symbolists were much taken by Parsifal for some strange and interesting reasons, so I’m looking forward to your remarks on this cycle’s bonus reel.

@Edward, the elves never fell like men did. They didn’t suffer from original sin. Therefore, Valinor isn’t utopia for them, it’s just how things are supposed to be, just like it would be for men, if they weren’t fallen.

Is it significant that Alberich doesn’t appear to die at the end, either?

Tolkien did put a deliberate twist in it for his ring, like Wagner, no one could throw it in, unlike Wagner, being Christian, his off-scene god had engineered the right characters to be in the Sammath Naur at just the right time, and Eru Iluvatar intervened to trip Gollum over the edge. Wagner wouldn’t have ever been able to write that, not having any all powerful god, and also, not being so prone to happy endings.

I do wonder if the challenges with Wagner are that he was decidedly non Piscean in his thought, and the Piscean age hadn’t ended. In a way he foreshadowed the change of the ages, although I don’t know anything about Parsifal, other than it invented the leitmotif, to be able to say if he mapped out a way forward for the individual.

JMG,

I know you’ve written some about Oswald Spengler and his theories; do you know whether Spengler was in any way an occultist?

Rhydlyd, no, I didn’t — that’s Delville enlivened with about 500 mikes’ worth of blotter paper, but you’re right that the resemblance is there. It irritates me that the local used-record venues haven’t yet brought me any Hawkwind!

Tortoise, very likely, but I’m not sure what to make of it. Quite possibly it’s an acknowledgment that the possibility of commodification is always there.

Peter, nah, there are leitmotifs already in The Flying Dutchman, and buckets of them in The Ring. As for the solution Wagner proposed, we’ll get to that!

Kabuki, no, he wasn’t — quite the contrary, he was a hardcore rationalist.

Another fantastic instalment JMG, Wagner really was a genius wasn’t he?

It must have been very traumatic for him to actually write this final part, I imagine his personality, plus his obvious love for his art, kept him from a Nietzschean end.

I finished Dune, as well as Dune Messiah. I think I remember you weren’t a fan of, was it the books after the first three?

I can see some parallel themes. None of the characters, although Paul was somewhat “heroic”, are in any way, “good guys”. Paul, unlike Siegfried was aware of his trajectory and hated it, although he didn’t feel that he had any choice but to go through with his apparent destiny.

I suppose walking off into the desert was his into the Rhine moment!

I wonder if the Tolkien mythos leaves some of us a bit annoyed, because it doesn’t actually parallel how life works. We might like it to go that way, but its a bit of a con job really.

Wagner’s tale, although it makes you uncomfortable, is closer to reality. Better to face facts.

A bit off topic, but I also, have been feeling somewhat uncomfortable of late, due to uncomfortable facts.

Once again we are going through another hot, dry, miserable summer. I think Western and South Australia are the equivalent of California, Arizona, Nevada, etc.

This, in Celcius was our last 4 day’s daily high and low?? temps and today’s is the last figure:

40.5 °C / 21.5 °C 41.2 °C / 23.8 °C 35.0 °C / 24.6 °C 30.9 °C / 17.2 °C 32.9 °C / 16.2 °C

It’s been like this pretty much since December last year.

We’ve got more heat to look forward too as well, with mostly mid to high 30’s and another 39 and a 40 next week .

Our rainfall, meagre at the best of times, has over the past year been mostly insignificant, the largest monthly total was 83.8 m, the next best 51.2 mm. Most monthly totals really equate to basically nothing, because they are generally made up of a few mm here and there. Anything under 10 mm really equates to nothing.

As a gardener, I’m feeling pretty flat, and wonder if it’s actually worth growing annuals over summer at all. I just requires too much watering.

Our measly water storage of of 192,496 is at 40.4% – 77,744 ML.

We have no major rivers or lakes, we do have the end of the Murray , but that is always over extracted:

In 1981, the Murray Mouth filled with sand and closed for the first time in recorded history.

Since then, the Murray Mouth has required regular dredging.

In recent years, the Murray Mouth has required almost continuous dredging.

The response by the dimwits that make up our “Leaders” is to simply let more and more people in.

Perfectly good solid brick houses, with a garden with trees etc are constantly demolished, and in the space 3 houses from street to back fence are erected. Usually with a dark grey steel roof, to match the road! So any meagre drops of water no longer find their way onto the land, but are caught in the gutters and go down the drain.

I could go on about may other things, but I ‘ll spare you.

I will say, that although you believe Europe is facing a Gotterdamerung, I actually think Australia is in the worst position of all the West. You have no idea how stupid, and bought and paid for, our politicians are.

And if spud head Dutton gets in as Prime Minister in the upcoming election, our participation in a potential War with China is practically guaranteed. We rely almost totally on imports and a blockade by China would be almost a certainty. Then they will probably expect our total surrender.

It may sound over the top (I don’t think so) and I certainly hope it doesn’t come to this.

Happy days!

Kind regards,

Helen in Oz

@JMG,

Thank you for another fun Wagner essay. The Age of Gods -> Age of Heroes -> Age of Men business seems extremely pervasive… not only does Tolkien copy it in his work (including that staple of mythology, ancient heroes with extremely long lifespans that get longer the further back you go) but it seems to me you can find elements of it in pretty-much any mythology you look at.

Why is the Christian God up to the challenge of flooding the whole earth in Noah’s day; by Moses’ time a millennium or two later he’s not doing anything quite so big but can still drown Pharoah’s army in the Red Sea while 600,000 Israelites watch; a thousand years after that you see Judas Macabbeus winning battles against long odds and giving God the credit, but he never (for instance) kills three thousand men with the jawbone of an ass. Jesus’ healing and resurrection are supposed to be the big miracles that the whole story is building up to, but at most a few hundred people witness them and get converted… very different from Moses with his 600,000! And then of course on the longevity front, biblical figures like Methuselah (who lived to be 969) are featherweights when compared with the earliest Sumerian and Chinese culture heroes, who topped out somewhere above forty thousand years.

On the one hand, thinking hard about this makes one really reconsider the worldview in which orthodox Christianity, Judaism, Islam, etc. make any sense. On the other hand, I do wonder – as an occultist and a Druid, do you think there’s any truth behind this extremely common theme of the “elder days” or an intensely magical deep past full of Gods and heroes, who gradually yield the stage to less and less magical varieties of men? And is there actually something real behind the extreme ancient longevity motif that shows up so reluably in so many different cultures?

@Kabuki

In Volume II of The Decline of the West, Spengler dismissed occult & Eastern religious practice from the Western intelligentsia of his time as “toying with myths no one really believes” and filling the role fantasy fiction does today.

However, I don’t think materialism is a satisfying explanation for the existence and development of High Cultures. Do currents of energy flow out of regions of the Earth like mantle plumes (probably ascending to the mental plane of meaning by the time they reach the surface) and humans respond to living within one by developing High Cultures?

“The idea of Liberty dies in flames” is indeed a powerful ending, and one that resonates with my recent thoughts.

I read many people who look forward to the end of what they call the American empire or some variation thereof. Many of those people are Westerners with political ideas that may be outside of the current Western mainstream but are still derived from the post-Enlightenment European political tradition. A large subset of that subset appears to expect “the end of empire” to result in the triumph of those ideas: something like a worldwide shift towards egalitarianism and democracy. I can see why this vision might appeal, but the likelier thing is that as Western civilisation loses ground, which seems like a largely unavoidable process, so do the ideas it promotes and is associated with. Also, if/when total collapse comes, it won’t be a triumph of liberty. It never has been – the kingdoms set up on Roman ruins weren’t exactly egalitarian utopias – though it may have some other upsides.

The cycle of sellouts you describe, by the way, can be seen in its purest form in countries that haven’t had a drastic (as opposed to gradual and partial) changeover of elites since the 18th century. Here in Russia, it can also be observed but in a more complicated form. The Bolsheviks, for example, never sold out; the original generation died trying to make their dream come true over the corpses of their “captive audience” and each other. But many other idealistic revolutionaries and free thinkers sold out to them. The remarkable late-Rusisan Imperial striving for liberty produced a fire that almost totally destroyed the intellectual milieu from which it rose, and the ideas of an emancipatory revolution or working-class politics have been tarnished by it for a large part of the population to this day. In the 90s, something similar though less bloody happened again, and again a new generation of freedom-loving intellectuals, the so-called Masters of Culture, flocked to support the new rulers (themselves either unscrupulous careerists or unbending liberal fanatics, not sellouts in most cases) and demand harsh measures against everyone they hate. The effect has been to discredit the ideas of liberty, democracy and human rights, and those who hold to them, for what is probably a majority of the population. It’s easier to like those things when they aren’t being brandished as weapons against you. The censorship our liberals complain about (very reasonably, I might add!) has been another product of their campaigns against nationalists and communists.

For my own part, I like to distinguish between Liberty as an abstract ideal and specific freedoms. The latter are very often useful and good, sometimes downright necessary and very much worth protecting and expanding. The former seems dubious at best, at least when it is portrayed as the only important thing, an end in itself, without any consideration of how this ideal interfaces with reality. For one thing, its adherents often seem to commit to it in disastrously counterproductive ways or else (maybe that should be “and subsequently”?) abandon it entirely, with grave consequences for the actual freedoms bound up with them. For while I like to make the distinction between Liberty and freedoms, and think the former concept requires a more critical approach, I fear what usually happens when people turn against it is that the baby gets thrown out with the bathwater.

Thank you for these posts! Just what I need to hear now in the middle of all craziness going on. I just received a heads-up from Berlin Staatsoper for 2 rounds of the Ring in the autumn, September-October. I am a bit tempted, although staying in Berlin that long (a week) is daunting – my love-hate relationship to that city can handle 3 days nicely, 5 days and I start to crumble. Like a lot of old, old european cities, the history with all its layers of terror and glory somehow seeps through into me, and mental digesting is hard. But thanks to that, Wagner in Berlin packs a special punch for me. It is not really cheap, though. The cheapest tickets have severely limited view of the scene.

Chris@Fernglade points out an obvious thing: all characters could have quit their grasping anytime, and changed the course of events. I do not know if burning it all up and starting anew will make much difference, when the grasping with violent means is still the go-to strategy. It even smacks of a narcissistic strategy of running away when the just desserts of your actions come knocking at the door. Dying is an escape from a self-manufactured catastrophe. Also: only getting punished after using the grasping strategy succesfully (more or less) a long time is not a good strategy of education. Some buddhist teaching story says that it is useless to beat up the pig when it is already in the cabbage field. Restraint is not an easy virtue for humans, and definitely important to be reminded of that as often as possible. But does it help when the takings are rich and getting richer every day? What would the current president of Ukraine say?

https://www.staatsoper-berlin.de/de/spielplan/ring/

Zarcayce, ” Gaza is Israel’s as far as I understand” – no it’s not. It’s Palestinian land, Israel’s occupation of Palestinians lands has been ruled as illegal under international law, and if you yourself were threatened with ethic cleansing I don’t think you’d find it so hilarious. Especially after everything the Palestinians have gone through. I get it that this is just what Trump does, spouting random stuff to keep everyone on edge and distract from his actual plans (assuming there are any), but I don’t think it’s funny anymore and I think the world is getting fed up with these games and threats.

Wonderful set of essays. Has made me rethink a few thoughts I had about the work – especially the part of Waltrude going on Brunnhilde.

One thing bugs me, though – what was sacrificial about Brunnhilde’s final act? Had she done what she did and the Gods bowed down to the Rhimemaidens, then maybe I could see the act as a sacrifice, but I’ve only seen it as a necessary act of destruction complete with a recognition that, with nothing to live for, it would be better to die with your former compatriots.

Note that this issue didn’t start with you – for some reason “Brunnhilde’s self-sacrifice” seems to be the party line. I’ve even seen it in The Met’s “Opera For Children” books.

“Hari Seldon is a fine example of why the twilight of the intellectuals can’t be mitigated. There’s something profoundly tragic and relevant in that scene where his projected image is rabbiting on about what should have happened next, when the rise of the Mule has thrown his entire scheme of future history into an interplanetary dustbin. ”

Very true. I should revisit the Foundation books. It’s been awhile since I read them, and only once.

The Mule and his random rise and his ability to turn enemies into allies, and otherwise dash the hopes of Seldon and the Foundation do seem very apropos just now. Some things really are unpredictable no matter how good your math. Overlooked by the intellectuals, and then derided, his power continually solidifying…

https://theartofmichaelwhelan.substack.com/p/the-mule

This image of the Mule by SF artist Michael Whelan shows just how much of a trickster and change element he is:

https://theartofmichaelwhelan.substack.com/p/the-mule

As for Crowley, no argument there.

What do you make of the change in Brunnhilde’s leitmotif post-Siegfried? It’s as if Liberty goes from being something wild and even ferocious to something domesticated and even submissive, and it takes betrayal to bring back the old fire.

Is rumor correct that Parsival is “Part-the-veil” in old lingo?

@31 Gaia Baracetti

Yes. If people here subscribed to certain accounts on X, they’d see the graphic videos of starving children being murdered, and wouldn’t find Trump’s comments about Gaza (or anything he or Biden administration did about Israel) so funny anymore. I only rarely watch them to preserve my mental health.

Our fate is in motion

You can thank your lord

Rhine Maidens are coming

for their golden hoard

The end is arriving

abandon your sword

Rhine Maidens are coming

for their golden hoard

Revelation is here

you will not be bored

Rhine Maidens are coming

for their golden hoard

Helen, I like the original novel Dune; even the best of the sequels are third-rate in comparison, and I haven’t read any of them in years. Tolkien — well, keep in mind that he was a devout Christian and felt he had to make his novels theologically correct, complete with the happy ending. As far as your local weather, ouch. It wouldn’t surprise me if Australia has a really ghastly fate — it’s a very marginal environment for human habitation, and I’ve read accounts by a good many people who’ve been there and sensed something deep in the land that is actively hostile to human beings…and hungry. Then, of course, there’s China; quite a few SF writers back in the day assumed as a matter of course that Australia would eventually be conquered by the Chinese, and I’m far from sure they were wrong.

Sandwiches, the idea that magic and miracles were more powerful in the past is very widespread, and there may be something to it; Native American philosopher Vine Deloria Jr. wrote a book entitled The World We Used To Live In presenting evidence that medicine people could do things in the fairly recent past that they can’t do any more. I’m open to the possibility that people lived longer, too, but there are a couple of confounding factors.

First, there’s some reason to think that in very ancient times, people counted time by the Moon rather than the seasonal cycle, and old traditions and records listing ages in moons were later read by people who counted age by suns, with resulting confusion. Methuselah’s age of 969 makes good sense if it was 969 moons, which is a little short of 81 years! Second, it was once standard practice for certain people to be buried alive in mounds and there become guardian spirits of their tribe or village, stepping out of the cycle of reincarnation for a while; eventually the mound was opened, the remains taken out and exposed on a hilltop to free the spirit, and a new guardian took the old one’s place. It would surprise me if any of them were left there for more than 3000 years (40,000 moons), but it’s possible.

Daniil, I know. I like to remind people that when the British Empire went down, there were three contenders to replace it — the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and the United States. Would people really have been happier if one of the other two took power instead? In the same way, if China replaces the US as global hegemon, things will doubtless improve for a while — a new hegemon is generally better behaved than an old and decadent one — but in a century or two the burden of empire will drag China down the same path, or they’ll step back as they did in the 1400s and some other nation will take the same role, as Spain did back then.

Liberty is a high ideal, and like most high ideals it’s lethal when it isn’t adequately balanced by countervailing ideals. For a great many people, the liberty they want is the liberty to persecute the people they don’t like, and advance the interests of their region or culture or class at the expense of everyone else. Humans being human, that’s the way it too often works out. Thus I think one of the things Wagner was saying with the plot of this opera is that liberty pursued as an end in itself cancels itself out, and perishes in the flames it kindles.

Kristiina, I envy you that! I grant that European cities can be psychically rough, but if I had the option I’d probably put up with Berlin for a week. As for your point, granted — and that’s something Wagner will try to address when we go on to what, for all practical purposes, is the fifth Ring opera.

Donald, it depends on your definition of sacrifice, of course. As we’ll see, the sacrifice of one’s own liberty to a higher aim is one of the themes of the last phase of Wagner’s thought.

Edward Etc., to my mind Michael Whelan is the best of SF cover artists; in a less moronic society his paintings would adorn cathedrals and national capitols, rather than cheaply printed paperbacks. That image of the Mule is a case in point, catching not only the Mule’s trickster nature but also his personal tragedy. It’s brilliant.

Roldy, that’s important to the plot. Part of the punishment that Wotan inflicts on Brunnhilde is that she will become an ordinary mortal woman once somebody takes her as a bride. It takes betrayal and tragedy to force her to rise for a moment to her former stature, and then die.

dZanni, no, it’s “pierce the valley” — perce-vale in the older spelling. One French version calls him Perlesvaus, per les vaux (“through the valleys”) in modern French.

Dobbs, that’s not half bad. Thank you.

@29 Daniil Adamov

I’m also thinking we Americans should replace “universal human rights” with “rights for Americans.” Countries working with that conception of rights can adopt what specific freedoms work well in their societies, rather than trying to adopt whatever currently fashionable “one size fits all” Unalienable* Universal Human Rights.

*The claim that rights that are perpetually being tweaked amd often under attack are “unalienable” is one of the most dishonest ever.

“Part of the punishment that Wotan inflicts on Brunnhilde is that she will become an ordinary mortal woman once somebody takes her as a bride. It takes betrayal and tragedy to force her to rise for a moment to her former stature, and then die.”

As an allegory of the ideal of liberty, that seems to imply she exists in two modes: Liberty Leading the People on the Barricades and Liberty Being Invoked Incessantly in Parliament. At first she was the former, then she was tricked into settling down with the political elites to become the latter, but (Wagner predicted) when this all comes crashing down she will go back to being the former… for one final performance.

@JMG

One of the major planks of post-imperial US foreign policy must be to retain independence from China, even if it makes us a pariah in the “international community.”

Well, you’ve done it again, JMG. This is about the best short summary of what is at issue in The Twilight of the Gods – what the opera is ABOUT – that I’ve ever read (and I’ve read many summaries and longer disquisitions.)

I might plea for just a bit more focus on Hagen. Perhaps the most overwhelming experience I ever had in an opera house occurred back in 1991 (?) when I attended a performance of Twilight at the Met. The great Finnish bass Matti Salminen sang Hagen and when he roused the Gibichungs I thought he was going to blow the roof off the Met. I had never encountered in all of art such a bone-shaking, terrifying rendition of pure evil.

Hagen is rousing the male group. Male group dynamics – for good or for evil – were an increasing pre-occupation of Wagner’s. Male groups are there at key points in Flying Dutchman, Tannhauser, and Tristan. They disappear from the Ring (instead we get a female group in Valkyrie and what a group it is) until Hagen awakens the latent power of the male group in Act 2 of Twilight. Wagner had, in the Mastersingers, subtly and sublimely depicted the male group, led by honorable men and constrained by history, culture, tradition and the demands of a fully realized adult sexuality, as the central pillar of a civilized order, In Twilight, he shows us the reverse – the male group responding to nothing but the lure of power.

One does well to remember how close Hagen came to taking the Ring for himself. Wagner gives us a glimpse – more than glimpse – of the sort of world that would have ensued. Was Wagner warning us of the totalitarian horrors that awaited Europe? I think he was and alas, in this as in so much else, he was an extraordinary prophet.

In Parsifal, of course, the male group – corrupted and diseased – takes center stage. I eagerly await your insights!

I second the idea of turning this discussion into a book. I’d want a physical copy of it. Maybe one of the self-publication companies ?

I repeat myself, but man, great series! Thanks

“intensely magical deep past full of Gods and heroes, who gradually yield the stage to less and less magical varieties of men?”

Larry Niven wrote a series of stories on that theme. The main character was the Warlock. The premiss was that magic was powered by a non-renewable substance called Mana. As the mana supply dropped what was achievable by magic also dropped.

The stories I remember right off are “Not long before the end”, “What good is a glass dagger”, and “When the magic goes away.”

The decline of wonder is a common theme. In Game of Thrones you have Valerian Steel which no one knows how to make anymore. All they can do is recycle what they have.

The knowledge of how to build Orthanc is lost in the Lord of the Rings as well as many other things. In the real world lost wax casting had to be rediscovered, and although metallurgists think they know how Damascus steel was made, modern ethics frown on case hardening the sword by running the white hot blade through an Ethiopian slave.

Although I haven’t had much to say on Jung or the Ring Cycle, I have really enjoyed the articles.

It seems to me that one of the most concrete lessons the Ring Cycle has for us mortals in the current time is the way it ended with the collapse of the system of commodification that was at the center of the Opera’s narrative.

We of course, live in an empire that represents the ultimate in commodification and financialization of all things, from people to nature. As this empire crumbles, Wagner reminds us that we must look towards other arrangements beyond the financial economy. Attempting to soften the ride down the slope of collapse by holding gold, cash or stock portfolios will be futile as the world reverts to a system of exchange, barter, duty and obligation.

Speaking of the failure of materialism, many old materialists have recently been complaining about the current decline of the scientific community, and these phenomena have reached a point where they can no longer ignore them.

https://whyevolutionistrue.com/2025/02/06/two-eyed-seeing-the-advantageous-of-combining-a-modern-scientific-with-an-indigenous-perspective-touted-in-nature/

According to the complaint of why evolution is true, we can see the process of scientific decline from an example

1. The papers themselves started to get longer and longer, but the progress made was getting closer and closer to zero.The 1953 paper in Nature by Watson and Crick positing a structure for DNA is about one page long, while the Wilkins et al. and Franklin and Gosling papers in the same issue are about two pages each. Altogether, these five pages resulted in three Nobel Prizes.Sadly, such concision has fallen. This new paper in Nature (below) is 10.25 pages long, more than twice as long as the entire set of three DNA papers. And yet it provides nothing even close to the earlier scientific advances.

2. The papers themselves are becoming more and more ideological, rather than producing objective knowledge related to reality (in fact, the objectivity of knowledge is being devalued). the paper calls “Western” neuroscientists “settler colonialists,” which immediately tells you where this paper is coming from.

3. Taking spirituality or sacred things (as long as they are not Christian) seriously as part of theory is beginning to be encouraged in the scientific community.For example:We build upon the foundational framework of Two-Eyed Seeing to explore approaches to sharing sacred knowledge…

Despite this, the old materialists still believe that if they can eliminate the poison of left-wing ideology on science, they will be able to return to the era when three Nobel Prizes could be won for a five-page paper.

But perhaps “left postmodernism” is actually the result rather than the cause of the scientific community’s inability to produce more effective objective knowledge, a method that scientists are forced to adopt to avoid unemployment. It is as if physics abandoned positivism because further experiments were no longer possible.

Gaia Barcetti @ 31 & Zarcayce @ 6: Greenlanders, Canadians and Panamanians can now rest easy. All remaining American treasure is to be spilled in the sands of Gaza so that Our President can have his Win–Peace in the Middle East!!, his supporters can be bribed with shares of Mediterranean beachfront condos, and his good buddy Benny will, he fondly imagines, activate the same networks of influence that arranged a Peace Prize for Eli Weisel. Nothing against the latter, BTW, of whose mellifluous writing I happen to be a fan. Please note the timing of the Natanyahoo visit. Talk of Panama, etc., brought him running hotfoot to DC to get his hand in the till first.

Jimmy Carter did it the right way and did it better. Not one drop of American blood was spilled to bring about the Camp David Accords. Best president of my lifetime.

I think that when Patrick Henry and others were speaking, orating in Henry’s case, about liberty, what they meant was no foreign domination of the then colonies, and no feudalism imposed on American workingmen. In our time, that fine old word has been perverted to mean I should get to do and have whatever I want, with advertising induced desires redefined as needs.

Chinese civilization is extremely resource intensive, despite the celebrated frugality of Chinese people. I question whether a warming and drying Australia could support it. A future military occupation could happen. I am inclined to think Chinese eyes are firmly fixed on the warming Arctic.

Patrick, yes. I’ve seen those mutilated children here in my home town in Italy, about a year ago, the few “lucky” ones that were able to come here to get treatment. They were trying to play on their wheelchairs, because they had no legs, while the local children ran around on the grass like children are supposed to do. And this was but the tiniest fraction of what’s happened to Palestinian children, due almost exclusively to American bombs.

For all the talk about how the American empire is doomed, and the American elites are clueless, there sure seems to be a lot of acceptance among certain people for crimes committed by their chosen candidate, either one of them, they are the same in this respect.

JMG,

Would you be so kind as to provide a quick summary of the characters and what they represent in Wagner’s view? Something like:

Wotan = elite intelligentsia of the time

Brunhilde = liberty

Siegfried = idealistic rebellion

Rhinemaidens = wealth of nature/natural commons

Hagen = ?

The way you’ve described all this in a really digestible for such a far off subject, but keeping track of the representations can be difficult. Fascinating essays. Thank you.

@Mary Bennett #47: I remember reading a quote from an ordinary man on the side of the American Revolution explaining “‘They’ (the British) wouldn’t let us govern ourselves.” To him, the issue was, do we govern ourselves? Or do others govern us?

Hi John Michael,

Thanks! 🙂

Hmm. I’m of the opinion that it is the role of the Elder to remind us lesser folks, that there are limits.

Man, the land down here is harsh. It’s an old land too and has known much. It’s my belief that it is best down here to work with the land, and whilst you can tweak the outcomes, the larger narrative is fixed. Already a number of large cities rely on desalination for drinking water (I rely upon rainwater alone), and it seems totally weird to me that the electricity system powering those monster machines would be kicked around like a political and ideological football – whilst adding more people into the mix. That story will not work out.

Cheers

Chris

Recently I watched the Shogun series which started on Hulu last year. While dots on screen are not the best way to transfer ideas, I found a lot of the ideas in the series to be strikingly similar to what has been transmitted in this discussion of the Nibelung, from the Lords and Regents being an aristocracy trying to keep and salvage their ideals from the past, to the women being both a force to manipulate and ultimately explode the current system. That is to say, these ideas are found in many cultures, and find themselves in many periods of time across the world.

Reflecting on the story of Shogun, and the story of the Nibelung, many of the ideas reflected here in Ecosophia and the Archdruid Report presented themselves. One especially, about limits rears itself to me. It seems that in the climactic reaches of a civilization, the old stories, the myths are ignored. One of the things taught in those myths are limits. Eventually we will reach those limits. Because they are ignored, we fail to see our own end nearing. It’s a tragedy in a way that it continues, but one lesson from Shogun was to consider flowers and their beauty, and how they could not be flowers without this process of living and dying. I’m certain there is a similar allegory in the Nibelung, perhaps I have missed it. Or perhaps this is where Parsifal comes in..

@46

The sciences are adopting left-postmodernist terminology because the current ruling class is woke and scientists want money. The vast majority of the population in America, never mind Europe, doesn’t give a fig about Native American beliefs (but doesn’t want to be branded “racist”– especially the PMC).

Of course, if Western art, science, technology, and general prosperity had continued advancing, critical theory wouldn’t be popular.

“Jimmy Carter did it the right way and did it better. Not one drop of American blood was spilled to bring about the Camp David Accords.”

And yet the Camp David Accords solved nothing or Gaza wouldn’t be a problem today.

Bill Clinton gave it the old college try as well. He talked, wheedled, bribed, and coerced both sides. And yet he also failed. The hate is too strong.

Re: Gaia 31 and Patrick re: zarcayce

https://open.substack.com/pub/jonathancook/p/the-gaza-war-was-a-lie-as-is-the

Like Patrick I only watch a little bit because I feel I shouldn’t turn away but I don’t know what I can do and I’m not great at just taking in horror and tradgedy for which I have no remedy and sitting with it. Maybe I should watch more opera to practice. Or just keep my nose on the grindstone where I feel like I can be of service.

It’s the first Tyler Childers song I learned when he was coming up in our home country. https://youtu.be/_QzcrflqDCg?si=-HaXYVxKLw2p709q

Daniil, exactly. That’s what he’s saying, and I don’t think he’s mistaken.

Patrick, why do you think the Trumpistas are cozying up to India so enthusiastically? If you don’t want to be aligned with one rising hegemon, aligning with another is a good plan.

Tag, I wish I’d heard that! I’ll give some thought to Hagen and see if I can add something to the book version.

Thibault, duly noted! I think one way or another something will happen.

Siliconguy, Niven’s stories about mana depletion are fine work, and perhaps the most Seventies of all fantasy fiction. 😉

Clay, yep. What’s more, “collapse now and avoid the rush” applies here as well.

林龜儒 , good. Very good. It’s beginning to sink in — just beginning, but the first signs are there — that the law of diminishing returns applies to scientific research too.

Gaia (if I may), no one’s hands are bloodless; they never are. Europeans can afford to preen themselves on their moral superiority only because they’ve been a wholly owned subsidiary of the American empire since 1945 — and even there, a lot of Russian children in the Donbass have had limbs blown off because the EU has so enthusiastically funded and supplied the proxy war in Ukraine. It’ll be interesting to see what happens now that the US is backing out of its imperial role in Europe and your nation gets to function as an independent power on the world stage.

Mike, it’s not quite so simple as that, because each character represents (a) a philosophical principle, (b) a social class, and (c) an actual character shaped by the demands of the drama. I’ll see what I can do, though.

Chris, no, that story won’t end well.

Prizm, do you happen to know how well the miniseries tracked Clavell’s novel? I’m familiar with that — I read it many years ago — and it’s modeled on a period of Japanese history I know tolerably well, with Tokugawa Ieyasu playing the role assigned to Toranaga in the book. As for those flowers, keep them in mind. Flowers will play two very important roles in the opera to come.

Prizm, you might perhaps enjoy Eiji Yoshikawa’s Musashi, his (very) fictionalized account of the famous samurai.

Siliconguy, what the Camp David Accords did was stop Egypt and Israel from fighting each other. No successful treaty solves every problem.

JMG,

I unfortunately don’t know how well the 2024 miniseries followed Clavell’s work. It is something I intend to remedy though as my interest has been peaked. According to some comments I read from others who had read his work, they’ve all said it remains relatively true to his novel, and cited the same connection to history and attempts to parallel it with Will Adams being portrayed by Blackthorn and Ieyasu portrayed by Toranaga.

Flowers are things of beauty. I’m looking forward to hear more about them in the next installments of this NIbelung series.

When reading about the Gods, Heroes, and Men, I am reminded of the worlds of the Kabbalah and how the same event has correlates across the four worlds. The fact that wagner’s ideas have value along philosophical/economic lines in addition to their raw artistic values also reminds me of that intuition. The higher ideals of Wagner drain all the way down from the lofty heights of art to the gritty realities of the material world.

Not sure if I’m making any sense, but that was what I put together when reading this.

I have now finally read the libretto. Wagner’s additions to the story, like Waltraute’s visit to Brunhild, and Alberich’s meeting with Hagen, are the most interesting parts!

Götterdämmerung seems to have been enacted several times during the Third Reich, though perhaps not very often – I haven’t found exact numbers. The prohibition seems to have lasted only from 1943 onwards.

Without your commentary, I would have been at a total loss why (almost) everybody dies at the end. Why does Siegfried’s betrayal of one woman for another (under the influence!) lead to the destruction of everything? As a prophecy of the end of Western civilization it makes uncanny sense. This interpretation is also completely outside the field of vision of any major political movement today – liberals, conservatives, nationalists, populists, mainstream greens, even fascists, socialists, communists etc.