Yes, I know we had a presidential election here in the US yesterday. The remarkable thing about it, after a campaign season so packed with improbabilities and absurdities, is that it was a normal election, with no more than the usual amount of vote fraud and a winner declared by sunrise. While everyone recovers from their hangovers, let’s continue with our discussion of The Nibelung’s Ring; those of my readers who are paying attention may notice that what we’re exploring may not be quite as unrelated to the current situation in the US, and elsewhere in the industrial world, as it might seem at first glance.

The first installment of our tale, The Rhinegold, set out the problem the remaining three operas will explore. In the mythic language Wagner borrowed from Ludwig Feuerbach, this is straightforward enough: now that the gold from the bottom of the Rhine has been turned into a ring of power, is there any way that Alberich’s deed can be undone and the gold restored to the Rhine, or will the ring continue to pass from hand to hand, bringing doom to everyone it touches? Translate into the language of pre-Marxian socialism and the question becomes one that we’re still dealing with today.

Central Europe in Wagner’s time was still reeling from the initial impacts of the process by which human relationships stopped being the basic glue of society, and were replaced by a process of commodification that reduced all other values into those denominated in money. The older world of peasant village economics, governed by customary exchanges and community values, still survived in fragmentary form here and there in isolated rural areas, along with the folktales the Brothers Grimm and their friends collected so enthusiastically; the educated public, or that fraction of it that read works on cultural history, could learn all about the comparable world of urban community life, with its craft guilds and self-governing city-states, that had been swept away by industrialism.

It was heady stuff, and it made a harsh contrast with the world of economic and political centralization spreading rapidly across Europe from its English seedbed in Wagner’s time. That was particularly true, of course, for intellectuals who didn’t have any exposure to the sometimes bitter downsides of peasant life, with its narrow horizons, its stifling conformism, and its utter vulnerability to the vagaries of a fickle climate. To them, and of course to their many equivalents in later eras, rural village life came to be repainted in the hues of utopia. (Those of my readers who’ve followed the modern neoprimitivist movement will have seen the same sort of portrayals of hunter-gatherer societies, by the same sort of people, for the same reasons.)

The implications of this backward view through rose-colored glasses are rarely understood these days, not least because quite a few more recent socialists have been eager to cover up the less doctrinally correct dimensions of their own heritage. One of the major strains in pre-Marxist socialism, in fact, was profoundly conservative, even reactionary, in its focus. That form of socialism didn’t, as Marx and his followers did, cram the hoped-for transformation from capitalism to socialism into a theoretical scheme of social progress that defined socialism as the inevitable wave of the future. Instead, it portrayed capitalism as a temporary aberration, an intrusion into the natural scheme of things, which had to be swept away so that human society could find its way back to its normal state.

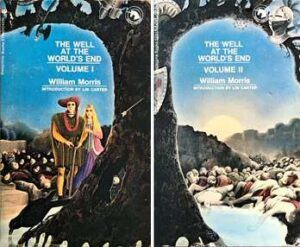

It’s not inappropriate, in fact, to refer to this sort of thinking as Traditionalist socialism. If you want to see it in full flower, the best English-language source is the writings of William Morris, which were mentioned earlier in this sequence of posts. In place of Morris’s fine socialist utopian novel News from Nowhere, though, you’ll want to read his even better epic fantasy novel The Well at the World’s End, which features exactly the sort of sturdy peasant culture that Wagner and other German socialists dreamed about in the exciting days before the 1848-1849 rebellions. It’s worth the time to read it, as it has a great deal more to offer than a glimpse at the older socialism; it includes a critique (veiled in mythic allegories almost precisely parallel to Wagner’s) of the entire social and political situation of Morris’s time.

The Marxist movement appears in his story as the Fellowship of the Dry Tree, and the Dry Tree itself is the terrible symbol of the universe of scientific materialism expressed most clearly, in Morris’s time, in the writings of Charles Darwin. That largely defined the core innovations that Marx brought to socialism: he linked the socialist movement to the mythology of progress and tried to claim the prestige of nineteenth-century materialist science for his theories. It was a clever move. Marx backed the winning horse in the late nineteenth century reality wars, and a later generation of socialists inspired by his theories rode that horse to temporary dominion over half the planet. It’s a very minor consequence of all this that Wagner’s allegory has become almost impossible for many people nowadays to grasp.

Make the effort to step outside of the cult of progress and look at the world in a different way, and what Wagner was trying to say becomes much easier to follow. During the years when he worked up the old legend of the Nibelung treasure into the plot of four operas, he was passionately convinced of the truth of the narrative I sketched out earlier: the idea that capitalism and its commodification of the world represented a temporary aberration, a breach in the natural order of things, that would go away forever if only its grip could once be broken. Alberich’s terrible deed marked the beginning of that aberration, but the folly of the gods and giants in falling into the same trap marked the point at which its jaws closed hard on the world. How could society break out of the trap, though? That was the question that he sought to answer using the paired tools of mythology and music.

I’ve mentioned before that one of the secrets behind the greatness of The Ring is that Wagner’s own ideas changed while he was writing and composing it. That’s important to watch here, but it’s also worth noting that Wagner started out with a clearer analysis than most of his (and our) contemporaries. Then as now, it’s standard for intellectuals to think of themselves as the forces for change that really matter, the ones whose ideas will set the pace for the future. That’s what Wotan thinks too. “The sum of the intellect of the present,” as Wagner called him, is profoundly dissatisfied with the forced compromise that left the power of commodification securely in the hands of the aristocratic elite. His goal in the second opera, The Valkyrie, is to go back on that compromise in some way indirect enough that he won’t be caught at it.

The problem, of course, is the same thing that undoes all his plans throughout the opera cycle: he’s ready, willing, and able to sacrifice anything and anybody for his goals except himself and his own interests. Self-aggrandizement is his overwhelming character flaw, and self-sacrifice—the one thing, as Wagner will argue, that can solve the problem posed by Alberich’s ring—is the one thing he can’t and won’t even conceive of doing. Wagner didn’t choose this detail of characterization at random. He recognized as clearly as anyone ever has that the craving for unearned power, and the collective egotism that drives it, are the besetting sins of the Western world’s intellectual class.

He was right, too. From the days when Greek philosophers began to draw up the first sketch of the Western mind, the one thing you could count on was that whenever intellectuals made proposals about bettering society, most of them would argue that intellectuals like themselves should be first in line at the feed trough under the new arrangements. When Plato proposed in his Republic that philosophers ought to run the world, he was simply putting in the most blatant possible form the will to power that pervades Western intellectual life.

He was also following in the footsteps of the founder of the tradition of Western philosophy, Pythagoras, the guy who coined the word “philosopher” and who first proposed that what undergirded the material cosmos was not a substance but an abstract intellectual structure of laws and numbers, was also the first person we know of in the Western tradition to try to park intellectuals at the top of the political pyramid. He succeeded for a while, too, by the simple expedient of getting all the leading political figures in the city-state of Crotona to become his students and embrace his ideas.

What happened in the slightly longer run makes a good object lesson to anyone who thinks the way Pythagoras did. Inevitably the ruling elite of Crotona applied the philosophy they’d been taught in ways that maximized their wealth and beggared everyone else, and insisted airily that since wisdom, justice, and truth were on their side, anyone who wanted to change things was simply an ignorant fool. The result was an uprising in which most of the students of Pythagoras were trapped inside the building where they met, and died when it was burnt to the ground. Pythagoras himself escaped, but died a short time later in the neighboring city of Metapontum, his dreams of a utopia of wisdom shattered.

You can see the same mistake the followers of Pythagoras made any time intellectuals set out to tell the rest of the world how they ought to live. Those of my readers who are familiar with the last few decades of self-proclaimed “deep thinking” can come up with plenty of examples. Marx did the same thing in a slightly more veiled form, proposing a “dictatorship of the proletariat” that inevitably works out in practice to a dictatorship of a faction of intellectuals who rule in the name of the working class. By and large, the only Western intellectuals who refuse the temptation are those who don’t believe that it’s possible to design a better society from scratch, and of course they’re in the minority.

Wotan doesn’t belong to that minority. Au contraire, as the archetype of the Western intellectual, his goal as the orchestra begins playing the prelude to The Valkyrie is to get the Ring into his own grubby hands once again without violating any of the agreements that give him his power. What’s more, he’s got a plan, and he’s been busy since the curtain came down on The Rhinegold getting all the pieces lined up.

In mythic language—well, let’s start by noting that if his wife Fricka wanted a divorce she’d have an easy time convincing the judge of her view of the case. The first thing Wotan did to further his plan was to go looking for Erda the Earth Mother, who popped up in the last scene of The Rhinegold to convince him to let go of the Ring. He found her and, well, they got very friendly. Nine bouncing baby warrior maidens resulted. They grow up into the Valkyries.

(And yes, if you’re suddenly thinking about Tolkien again, there’s a reason for that. In a very real sense, The Lord of the Rings is an edgy parody of The Nibelung’s Ring. Sauron, like Wotan, has only one eye, he’s chasing after a magic ring he had once and lost, and his head is full of plans and strategies and gimmicks. Oh, and he has nine servants who ride out on errands from his magic castle. Of course they’re not beautiful warrior maidens, they’re hideous undead wraiths, but then that’s part of the parody; where Wotan is a morally complex figure, at once the protagonist and the villain of his story, Sauron is pure unfiltered evil, an infinitely black backdrop Tolkien uses to silhouette the moral complexities of his protagonists.)

The Valkyries, as I was saying, then become Wotan’s human resources department. Yes, humans have now entered the story. In The Rhinegold, as my readers will doubtless recall, mere human beings were nowhere on the stage: it was all gods, giants, nature spirits and Nibelung dwarfs. Now there are humans. Norse mythology has plenty to say about how they happened, but none of that enters into our story. It’s one more reminder that the gods, giants, et al. in Wagner’s operas fill the role that Feuerbach assigned them, as allegorical figures reflecting classes and ideas in the human world. From this point on, though, the story is going to slip down bit by bit from the heights of Valhalla to the gritty realities of human life.

(Here again, Tolkien follows the same arc, though he does it in The Silmarillion rather than his more famous trilogy. That volume begins quite literally with a prologue in Heaven—the parallel with Goethe’s Faust is doubtless deliberate—and descends from there; in Tolkien’s own words, “If it has passed from the high and the beautiful to darkness and ruin, that was of old the fate of Arda Marred”—Arda, of course, being the world in which you and I live. Tolkien’s own highly traditional Catholic Christianity, with its doctrine that the Fall affected the world as well as the human species, is of course involved here, but it’s worth noting that Wagner, who was anything but Christian, traced out the same trajectory in his opera cycle.)

Wotan himself is an eager participant in that descent, and the second and third phases of his plan show that at work. The second phase, once he has the Valkyries safely installed in Valhalla, is to send them to harvest the bravest of slain warriors from battlefields to form a palace guard. He know that it’s possible that the giant Fafner might decide to use the power of the Ring against the gods, and he also knows that Alberich is scheming night and day to get the Ring back. His guard of warriors is there to stop them, even though he knows that the power of the Ring is such that this may not save him.

It’s the third phase of the plan that sets the plot of The Valkyrie in motion. Not satisfied with his dalliance with Erda, he also descends to the earth, adopts the pseudonym Wolf, and takes up with a human woman, fathering two children, Siegmund and Sieglinde. Things don’t go well for them; Wolf and Siegmund come back from hunting one day to find their home burnt to ashes, Siegmund’s mother slain by raiders and his sister gone. The two men live as outlaws for a while, and then Wolf vanishes too.

Sieglinde, it turns out, has been taken captive and sold to a chieftain named Hunding, who takes her as his wife. (Her wishes, of course, are not involved in this transaction.) Hunding’s hall has, oddly enough, a great ash tree growing right up through the middle of it. At the wedding feast, a mysterious stranger shows up and thrusts a magic sword through the trunk of the ash tree, saying that it belonged to anyone who could draw it out. You know the rest of that story, dear reader, in its Celtic variant, where it’s the Sword in the Stone rather than a sword in a tree; nobody could make it budge until the rightful heir of the sword comes along. That heir, of course, is Siegmund.

In other words, Wotan arranged all these events for his own purposes, including the murder of his human wife and the abduction and marital rape of his human daughter. As I noted in our last installment, for all his pretensions of divine glory, he’s basically a sleazeball, and his sleaziness stands out in stark relief in The Valkyrie. His goal is to toughen a mortal hero to the necessary degree of strength and fierceness, give him a magic sword, and then send him to kill Fafner, the giant who owns the Ring, who has used his stolen powers to turn himself into a gigantic dragon and now dwells in a cave, guarding his treasure. Since Wotan himself won’t be the one who kills Fafner, he thinks he has plausible deniability, and he can then get the Ring back and make his power secure forever. Given Wotan’s treatment of his mortal wife and daughter, what might happen to Siegmund if he doesn’t fork over the Ring promptly enough doesn’t bear considering.

Wagner got all the raw materials of his situation straight from Norse mythology. There, like so much of Norse myth, they had a cosmological dimension; the hall that has a mighty ash tree growing up through the center of it is of course the universe itself. The two rivals in the story also have deep roots. As the son of Wolf, Siegmund is a Wulfing, and the name Hunding literally means “son of the Dog;” the dog and the wolf, the tame and the wild, form one of the great cosmological pairings of the Northern tradition. (Weirdly, they also show up extensively in later alchemical literature, and the possibility of a connection between Norse myth and the lore of alchemy deserves much more exploration than it’s received so far.)

That said, Wagner didn’t have cosmology (or, for that matter, alchemy) in mind when he penned the libretto for The Valkyrie. Let’s put everything through his Feuerbachian filter and see what it becomes. Wotan, as we have seen, is the intelligentsia of nineteenth-century Europe, trying to find some way to evade the ghastly consequences of capitalist commodification while still clinging to the influence and wealth it got from the capitalist system. What are the children of the intellect? On the plane of gods and giants, they are ideals; that’s what the Valkyrie are. On the human plane, they are people motivated by those ideals. Among them are Siegmund, the archetypal rebel who is motivated by the ideal of freedom, and Hunding, who represents the establishment of his day and is motivated by the ideal of law.

We’ll discuss the other characters a little later on; they all have their own Feuerbachian meanings. All through the first half of the nineteenth century, the two ideals of liberty and law came into conflict over and over again, and—just as in Wagner’s libretto—the intelligentsia of the time fueled the conflict and did their best to keep it ablaze, without the least concern for the cost in human lives and suffering. The French philosophes who destabilized the French monarchy and aristocracy that paid their bills are only one example of the phenomenon, and of course it’s just as widespread now as it was then—witness the university professors who denounce in strident terms the very system that provides them with their salaries and benefits.

Then as now, these denunciations are phrased in terms of abstract principles, but it’s not exactly difficult to see through the filmy garments of justification to the seething, sweaty craving for unearned power beneath. Wagner’s diagnosis of what we may as well call “Wotan syndrome” remains as cogent today as it has ever been. As we’ll see, his prognosis of the course of the syndrome is just as exact. Wotan’s plan—in essence, to encourage rebellion against the existing order of society, in the hope of snatching power from the hands of the rebels once they seize it—is fatally flawed from the beginning. In our next installment, we’ll see what the flaw is and how it plays out in practice.

I’m really enjoying this series. Thank you for the recommendation to read “The Well at the World’s End.” I’ve added it to my list.

“Wotan’s plan—in essence, to encourage rebellion against the existing order of society, in the hope of snatching power from the hands of the rebels once they seize it—is fatally flawed from the beginning.”

Once again I catch a connection with my current reading: Barbara Kingsolver’s novel, “The Poisonwood Bible,” set during the 1960s Congo Crisis. The Eisenhower administraton planned to poison the rebel leader Lumumba with his toothpaste, but the plan was abandoned. (Perhaps the fatal flaw there was that the Congolese traditionally cleaned their teeth with wooden sticks, sans toothpaste.) In any case, Lumumba was eventually deposed and murdered. The problems of the crisis are unresolved, and the country remains subject to Western machinations.

I’m looking forward to your next installment about the fatal flaw in Wotan’s plan.

JMG, the phrase from this weeks essay, “Sweaty craving for unearned power beneath. Wagner’s diagnosis of what we may as well call “Wotan syndrome” “.

This seems to perfectly sum up the Kamala Campaign along with the woke movement in general. It seems that Kamala is the dead end of the religion of progress. Though spouting platitudes like ” moving forward”, she was an empty vessel with no new ideas or even excuses to support the religion of progress. Al Gore is a perfect counterpoint. Like him or not, he rode the belief of progress in the future with some ideas ( both good and bad).

All Kamal and her followers could say was,” anyone but her will make us go backward.”Almost as if they were admitting the gig was up.

Here I thought Sauron was a fictionalized Lucifer, the fallen angel of light. Mordor where the shadows lie being the land without light as well as an industrialized waste.

Some dates might help. Morris was born in 1834, so a generation later than Marx, b. 1819. The Well at the World’s End was published in 1896.

JMG,

I should probably read Faust directly, I’ve seen several adaptations to stage and film, but perhaps its time I made a pass at the original (or a translation, anyway).

I like how ridiculously flimsy Wotan’s ‘plausible deniability’ is. It reminds me of nearly every action or statement undertaken by a senior leader of a government agency (and I work for federal agencies!). So often, they’re covering their hindquarters with the rhetorical equivalent of saran wrap. I have been repeatedly surprised at how well those thin and transparent lies work in allowing miscreants to dodge consequences. I suppose that’s one reason why I’m unlikely to ever get to that level!

You’re leaving me hooked on the edge of my seat for the next installment!

John B.

Am loving each update to this story. It really is an epic tale and I find it fascinating.

Thanks John, I love the connections you make between the Ring mythology, social conditions, and esoteric knowledge. I look forward to the next installments

Dear Mr Greer

You said

” in its focus. That form of socialism didn’t, as Marx and his followers did, cram the hoped-for transformation from capitalism to socialism into a theoretical scheme of social progress that defined socialism as the inevitable wave of the future. Instead, it portrayed capitalism as a temporary aberration, an intrusion into the natural scheme of things, which had to be swept away so that human society could find its way back to its normal state.”

In a way the traditional socialists are right. Capitalism is a temporary aberration that is slowly going away due to the decline of industrial civilisation.

Jasmine

Looking at the moon tarot card I immediately thought of that bright yellow disc being something like a golden ring …

Every time you draw another parallel between Wagner’s Ring and Tolkien’s, I remember how much Tolkien claimed to loathe Wagner. But today I had an idea: Is it possible that part of Tolkien’s distaste for Wagner was because Wagner treated the gods as Feuerbachian images, and not as real Powers in their own right? Of course, doctrinally Tolkien was a Catholic and no polytheist; but I think his sympathies were clearly on the side of treating the Gods as Gods, and not as something so paltry as human ideals.

“Though all the crannies of the world we filled

with Elves and Goblins, though we dared to build

Gods and their houses out of dark and light,

and sowed the seed of dragons- ’twas our right

(used or misused). That right has not decayed:

we make still by the law in which we’re made.”

Maybe you (or someone else in the commentariat) already made this point in an earlier installment, in which case I apologize for forgetting it.

Goldenhawk, I’ve had Kingsolver’s book on my get-to list for a while. I’ll move it up a few notches.

Clay, one of the things that fascinates me about the whole campaign the Democrats ran this time was that it had no substantive content at all. We were supposed to vote for Harris because she was “brat,” whatever that means; then because of “joy;” then because Donald Trump was Donald Trump; then because Donald Trump was Hitler; then because Donald Trump was Hitler, Attila the Hun, Ming the Merciless, Monster Zero, and Batboy all rolled into one — and then the ceiling fell in. There was a time when the Democrats knew they had to offer voters a vision of a better future, but they’ve lost that completely: it’s all “you have to vote for us or things will get worse,” as though the current miserable mess is the best we can possibly hope for. I suspect that did more to doom them than anything else.

Mary, Mordor was those things also. Tolkien was anything but simpleminded; he wove a great many strands together into his fabric. As for Morris, yes; so?

Sirustalcelion, it’s worth reading, even in translation. Goethe is brilliant. As for Wotan’s attempt at plausible deniability, good — that’s one of the crucial difficulties, of course.

Kyle and Raymond, thank you! I try to keep it interesting.

Jasmine, that’s quite true. It’s just that Marxian socialism is even more vulnerable to the same effect!

KAN, given the symbolism of the card, that works quite well!

Hosea, that’s an intriguing idea and may well be involved in Tolkien’s dislike of Wagner. All things considered, I’m not sure there was anything in Wagner that wouldn’t irritate a crusty old hyperconservative Catholic like Tolkien!

Re. Wotan being “ready, willing, and able to sacrifice anything and anybody for his goals except himself and his own interests”: I find it striking how that’s such a specific inversion of the mythological Odin, who’s of course famous for sacrificing himself or parts of himself on several occasions. And also how his goal is to win power and knowledge for himself, but also for the wider community of humans and gods. Another interesting inversion with how he gives a wolf life here, while a wolf takes his life in the mythology.

Re. alchemy and Norse myth: Also intriguing, as someone who’s admittedly more into the Norse than alchemical side of things, but willing to learn. My immediate thought is that the link might be Snorri Sturlason, since he clearly partook of Continental intellectual culture and trends in other ways, and so much of what we know of the myths is colored by the lens of that one individual. Maybe that’s too simplistic, though.

Thank you for this most interesting essay, and thank you also for blithely disregarding current political events in this week’s essay (or almost)!

I think Jasmine is quite correct, and in fact we (or rather, our descendants) will eventually return to a less commodified, if also much less comfortable society. I will now have to read The Well at the World’s End (once I have finished Little, Big) to see if Morris imagined a realistic level of comfort…

From last weeks post, the British empire had many problems but overmanned bureaucracies was not one of them, that is a feature of the US and the Global American Empire.

https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/uksectoraccounts/compendium/economicreview/april2019/longtermtrendsinukemployment1861to2018#the-evolution-of-sectoral-distribution-of-employment

Fig 5b is the one to look at

Hope link works

JMG,

Western civilization features all these different ideas for political and economic systems – Marxism, socialism, anarchism, capitalism, and the list goes on and on with various schemes and combinations of schemes into Faustian infinity. Is this development of various schemes only a characteristic of Faustian culture? All the different “experts” out there seem sure that they have discovered and developed the one true scheme that will bring peace, love, harmony, sweetness, and everyone’s “best life” to all of humanity forever and ever, amen. How does it compare with other cultural types such as those Spengler identified? Maybe they have schemes, just not the infinitude?

Thank you for leading us on this fascinating Wagner tour. I never would have thunk it quite so entertaining and enlightening.

Will1000

Hi JMG and readership,

the theme of “intelligentsia stirring the pot hoping to ride the unleashed chaos” is quite interesting.

From my delvings into periferal spaces, I think that is one of the contributing factors to the rise of Donald Trump aswell. The likes of Peter Thiel and the John Birch Society, Turning Point Usa, Prager U propping up fringe intellectuals enlisted from the liminal spaces of the internet…these interest and advocacy groups being themselves propped up by Big Money interests (often tied to Big Tech, Big Oil, Big Car etc)

Of them all, Musk is probably the one whose claims you can take at face value…after all he admitted that he thinks AI will take over the world and he just wants to be there to see it in his lifetime…and securing a presidency which will not limit social media (muh free speech!) from which algorithms learn, nor put any brakes on the AI and satellite arms races, seem only the next logical thing to do…accellerate even more…

How do you think it will fare for them? Will they be able to control The Donald? Or will the young disinfranchised young men whose rage was carefully cultivated, be a time bomb which blows the chairs from under their buns?

Lots of young lonely american men from the gun community have been training for years for a civil war…spending their hard earned surplus income (which they are not spending on rising families) on gear and guns and courses…

Just the musings of an european spectator…

JMG it helps me understand events in history if I can get dates and the sequence of events straight in my mind. For example, I realized that WOTW was published nearly a half century after the revolts of 1848, so at a time when Marxism was a recognized presence in European thinking. I shall keep my chronological researches to myself in future.

Clay Dennis, oh, but I voted for Harris because I think she is a really nice lady whom I would feel comfy having a cup of tea with.

As always, thanks for your insight Dear Archdruid.

What came to mind in your various discussions of The Ring, specially the part where you spoke of the Fault’s deal of Pythagoras and his followers (an unknown detail I’ve found fascinating and horrifying in roughly the same measures) is this particular lines of the song Mis Tres Animales, by the Tucanes de Tijuana (disclaimer: these both are part of the Narcocorrido genre that is possible to share in polite company, but still… ).

El dinero en abundancia,

tambien es muy peligroso.

Por eso yo me lo gasto,

con mis amigos gustoso.

“Abundance of money, is a very dangerous thing. That’s why I spend it all, joyfully with my friends”.

I am thinking now that an abundance of knowledge, specially without the cultivation of wisdom, might be just as detrimental for one’s own safety. Furthermore, it is not something you can just spend. If anything sharing it with your friends may lead to an echo chamber where the group will encourage each other (and individually, try to outdo each other) into hoarding more of this exquisite brain fuel.

What’s an intellectual to do, then? Go daoist and claim to be happier in the mud that in the Emperor’s court?

Sirustalcelion (#4): “I like how ridiculously flimsy Wotan’s ‘plausible deniability’ is.” Just wait till you hear Fricka give him a royal reaming over it – she’s right, too, and he has to admit it.

My first thoughts about capitalism were the same as Jasmine’s. But then it occurred to me that capitalism is actually quite natural: it’s an extreme r-selected socioeconomic system (hopefully the most extreme the planet, or at least our species, will ever see).

Like any r-selected phenomenon, when the conditions are right for it, it will win. Trying to stop it during that period is a losing proposition. But also like any r-selected phenomenon, it will ultimately undermine the conditions that allow it to thrive, and that will be its doom.

It’s already done that to itself once, about a century ago, and maybe once before that. In the wake of the Great Depression and the rising tides of socialism and fascism, the brutal, nakedly exploitative form of 19th-century industrial capitalism was replaced by a moderately less aggressive variant — neoliberalism — that seems to be slamming up against its own limits now. I suspect we have a few more, even shorter-lived variants to go through over the next century or two.

Hi John Michael,

Rural life is quite physically demanding, and unlike a pay cheque (check in US parlance) from working in an office, factory etc., you spend all that time and energy, and despite your best efforts, still go hungry from a lack of returns. I’m in the traditional lean time right now where the plants are growing strongly, there’s much to be done, but there’s not a lot of produce to consume. I probably know enough now not to starve, but that assumes I can keep on bringing in soil resources from elsewhere. No, the only people who’d think this state of affairs is an idyll, are those who’ve not had to put their backs to a shovel and dig the soil. Still, I don’t want those folks lives with the descent into abstractions, reality is terrible, but unreality is far worse..

Wotan, that randy old goat of dubious moral character. What did he do with his power anyway? The results however, probably had a lot to do with recruiting posters over the past century or so… I’d not know previously that the Valkyrie were the equivalent of Tolkien’s dark rider ringwraiths.

Presumably Siegmund has some semblance to Aragorn?

The more the intelligentsia get behind such schemes, the more the people on the streets become wary, surly and unresponsive. What did they expect? The descent into unreality is far worse, and here we are today.

Cheers

Chris

I just wanted to let readers know that it turns out The Well at the World’s End is in the public domain, and is available as a free ebook on Amazon and on sites such as Project Gutenberg. I’m a few pages in and having fun so far.

Hi JMG,

I’m intrigued by your interpretation of the Dry Tree in the Well at the World’s End as a symbol of socialism. It’s been a while since I read it, but the Dry Tree was such a strange symbol, and I found it so ambiguous in the books, that even after I have forgotten most of the other details of the story I have found myself wondering at intervals what it was all about. How did you work out the connection to socialism? It went completely over my head.

I have to say, regarding that tarot card, that that snappy, chitininous crustacean reminds me if a certain entity egging-on the latter-day lunatic neo-cons vs. the jokey wokies .. each vying for dominance .. to their ultimate demise!

I am really enjoying your analyses of the Ring. I suppose it has to be said that Wagner’s interpretation of how societal bonds used to be more morally social before capitalism, just seems ridiculous. Historians generally agree that most of civilized history has consisted of a predatory upper class (aristocrats) ripping off peasants, workers, and so on. A typical year for farmers saw people from the city come and take some large percent of their crops with no money or goods in return. In his book Plagues and Peoples, the historian McNeill employs the term “microphage” for “smaller eaters,” that is, small beings like bacteria that live off humans, and invents the term “Macrophage” or “big eater,’ for the upper classes throughout history, the big organisms that live off other humans. I find “macrophage” to be a really satisfactory term (also applicable, of course, to the capitalist predators who took over). It’s impressive how much power an unjustified sentimental view of pre-capitalist history acquired,. Of course, the ugliness of capitalist factories and behavior certainly helped.

Now, substitute a squirrel and raccoon – both rabid … for those two canids, and well…??

Kim, that’s an excellent point. Wagner being Wagner, he won’t have let mere fact stand in the way of his artistic vision! As for Snorri, that’s an interesting suggestion. There seems to have been some overlap in the 17th century between Rosicrucian occultists in the Scandinavian countries and interest in the old myths, so that’s not impossible.

Aldarion, it’s a fine novel, but no, Morris donned the usual rose-colored glasses when looking at the Middle Ages.

JP, thanks for this. The link works fine.

Will1000, it really varies from great culture to great culture. China in its first intellectual golden age had quite a flurry of political and economic theories. Classical culture, by contrast, simply assumed as a matter of course that the polis was the natural political form of humanity and jerry-rigged various arrangements to manage nations of more than one polis. So it’s one of the variables. I’m glad you’re appreciating the journey!

Monkeypilled, that’s one of the big questions. I’ll be discussing that in some detail once we finish this sequence of posts. The new year is going to see some lively explorations.

Mary, I’m not asking you to keep chronology to yourself. It looked as though you were trying to make a point by citing the date, and I was curious about what the point was.

CR, it’s not an abundance of knowledge that becomes muy peligroso, it’s the mistaken notion that filling your head with abstractions makes you better qualified to deal with the real world than other people. Those of us who are enticed by the intellectual life need to understand that it’s basically a hobby; like most hobbies — say, knitting — it has its productive side, and it’s possible to put it to good use in its own context, but Pythagoras and all his heirs were and are dead wrong when they convinced themselves that intellectual achievement is the same thing as practical wisdom. I would argue, in fact, that intellectuals of all people are very nearly uniquely unsuited for political office, and should content themselves with the indirect power they can have by putting interesting ideas into circulation.

Slithy, that seems quite plausible. There have also been some briefer periods of protocapitalism, generally using big buildings full of slaves as their factories; the late Roman world was one of these periods. Here again, as you’ve indicated, it crashed and burned catastrophically as soon as conditions no longer supported it.

Chris, nah, Siegfried is Wagner’s great hero; he’s Siegmund’s son, and he reforges the Sword that was Broken. Aragorn is the anti-Siegfried, to a hair. We’ll get to that!

Jennifer, thanks for this!

Samurai,_47, nah, the Dry Tree is the image of Darwinian materialism. It’s a brilliant image — a dead tree hung with weapons and surrounded by countless corpses, located in the terrible desert that has to be crossed before you can reach the Well at the World’s End. To explain how that works, I’d have to do a commentary on Morris’s novel — which is not a bad idea, all things considered. The Fellowship of the Dry Tree, in constant conflict with the Burg of the Four Friths, is Marxist socialism specifically; they have the emblem of the Dry Tree on their surcoats because Marxists embrace Darwinian materialism and the whole misbegotten universe of 19th century scientific determinism. Morris is saying, “No, go beyond that, beyond the Dry Tree.”

Polecat, there’s that!

Michael, no, I’m emphatically not saying that society used to be more “morally social” before the rise of capitalism, though a case can probably be made that Wagner was saying that. I’m saying that society was united by human relationships rather than by commodified abstractions. Human relationships are not necessarily morally good! The bond that unites an abusive spouse to the victim of abuse is utterly personal. Equally, the feudal bond that united lord and vassal, highly personal though it was, permitted a great deal of abuse. It’s essential, to understand any of this, to drop the habit of flattening out such issues into a one-dimensional moral spectrum in which the only two options are “good” and “doubleplusungood.” The problem with commodification is ultimately not a moral problem; we’ll get into that as this discussion proceeds.

Polecat, I note with some fascination that just before Harris made her concession speech today, a squirrel ran across the platform. Peanut, thou art avenged!

It seems to me that Goethe, Wagner and Tolkien are not necessarily copying each other, but that this story (which Shakespeare riffed off of too in many different ways) is constantly retelling and hitting on the underlying mythic structure of the entirety of western European religious and philosophical thought, that descends from Germanic and Celtic myth.

There is a reason Spengler call it the Faustian culture.

“Inevitably the ruling elite of Crotona applied the philosophy they’d been taught in ways that maximized their wealth and beggared everyone else”

Can you recommend a source about this? – it sounds fascinating.

Speaking of Germany, hot off the press.

BERLIN, Nov 6 (Reuters) – Germany’s ruling coalition collapsed on Wednesday as Chancellor Olaf Scholz sacked his finance minister and paved the way for a snap election, triggering political chaos in Europe’s largest economy hours after Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election.

Fantastic introduction to the Valkyrie. In the old days when record companies packaged their operatic offerings in gorgeous box sets complete with libretti translated into four languages and page after page of learned plot summaries and commentary, you could have made a living writing for them.

I recently stumbled onto a two part lecture by Deryck Cooke for BBC on a musical analysis of key elements in the Ring, complete with polite trashing of other commentaries and an absolutely riveting musical dissection of the famous passage in Act 2 of the Valkyrie when the scales fall from Wotan’s eyes and he sees the trap he has created for himself which you wrote about above..

Bryan Magee called Cooke’s early death the greatest loss ever for Wagner studies — he had embarked on a multi-volume close analysis of the Ring, I Saw the World End, but he got only as far as the text of the four operas and the music of Rheingold. (Cooke is also well known for having taken the unfinished work of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony and shaping it into a performable version.)

You and others may find these lectures (“Thinking about the Ring”) interesting (I certainly did) — about 45 minutes each.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCuXcfOYTt4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_BOgxiJ3HDc

“…it portrayed capitalism as a temporary aberration, an intrusion into the natural scheme of things, which had to be swept away so that human society could find its way back to its normal state…”

Isn’t that the lesson of peak oil? That industrial civilization—if not capitalism per se—is a temporary aberration in human history?

And contrary to the claim of Traditionalist socialism or the modern climate change myth, there’s no need to fight it or sweep it away. It will recede on its own like the Hubbert’s pulse that it is.

I can now see why the Wagner operas deserve a whole series of posts. Quite the feast of history, mythology, ideology and social studies! I really appreciate the occasional diversions into Tolkien’s treatment of the same archetype or figure; it is certainly worth exploring.

I don’t know whether it is the exceptional lucidity of your writing this post or if I have been reading you for too long (maybe both?), but I anticipated several of your comparisons. When you were describing the Alberich’s foul deed and the predicament of how to rectify it I immediately thought about the fall from the Garden of Eden – and a couple of paragraphs later you mention it. Then, when you describe Siegmund and Wulfing as the dog and the wolf, I thought, “gee, that reminds me of the Moon card in the Rider-Waite tarot deck” – and, again, you draw the parallel. (I then proceeded to see whether the Marseilles deck also has the wolf and dog on The Moon card – and there it was! Looks like it’s been used in Tarot for quite some time)

It is interesting to see that Pythagoras was the dude who started the whole ‘intellectuals should rule’ idea. I’ve had mixed feelings about Pythagoras: yes, he was good at math and stuff, but I always got the impression that he was really deep into abstractions – which is always a ‘red flag’ to me. “Philosopher kings”? Bah – humbug! Maybe Pythagoras and his ilk was the ‘inspiration’ for the airy-fairy inhabitants of the flying island of Laputa in Gulliver’s Travels? (I don’t know) Traditionally in most parts of the world those who rule are warriors (those who have more than just ‘skin in the game’; they often put their life on the line for their people) rather than ‘the smartest guy in the room’.

You used the term “unearned power” several times in this post. Of course, examples of this situation in modern times are legion: in my own country (Canada) we have parliaments, chambers and municipal councils that are bursting at the seams with such people. I guess the question comes to mind, “how does one define ‘earned power’”? To my mind, earning power involves taking huge risks, performing heroic deeds and/or making major sacrifices for the sake of others rather than oneself, thereby earning the trust and affection of society. But if you could provide an explanation or description, it would be appreciated.

This is the literature course I should have had in college. My hat off to you (tin foil and all) for providing us something with real value.

Speaking of Peanut, is it just me or is the euthanizing of Peanut the squirrel shaping up to be the managerial elite’s Affair of the Necklace? The sort of screw-up that delegitimizes a regime is often something trivial, all things considered, and this seems to fit the bill: a small matter, objectively speaking, but an outrageous and unforced error all the same.

I can easily see Trump tearing apart the bureaucracy with the slogan “Look what they did to Peanut!”

Hello JMG,

” I note with some fascination that just before Harris made her concession speech today, a squirrel ran across the platform. Peanut, thou art avenged!” – not sure what you were talking about, didn’t see a squirrel before her speech, but I have my own squirrel story. Before the election, I was very preoccupied with my own life and found both candidates lacking many important qualities, so I didn’t vote. On the day of the election, I had a 4-hour surgery, came home, started reading the news, and came upon the squirrel story. I felt sad about the senseless death of an animal and terrified of the government that had the spare resources to stage a raid to apprehend a pet squirrel. This story gave me the emotional energy to schlep to the poll and cast my vote.

Mr. Greer, Outstanding!

“One of the major strains in pre-Marxist socialism, in fact, was profoundly conservative, even reactionary, in its focus.”

Many of the movements hailed as proletarian were actually attempts to avoid being pushed down into the proletariat, for example by agriculturalists or artisans.

A good description of the lives of early 19thC factory workers in England can be found in the novel, Mary Barton, by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Blue sun, “modern climate change myth”? There is nothing mythical about it. It is real, it is here and the effects are getting worse year by year. Have you ever seen a forest fire? I have. Whole trees going up like torches. Now, several decades later, it is not just trees and hillsides. Entire towns are being burnt to the ground.

PumpkinScone, maybe so, but so much of Tolkien looks to me like a deliberate inversion of Wagner that I think it was exactly that — among other things.

Justin, it’s been a long time since I read up on the history of the Pythagorean movement in Magna Graecia and I no longer have my notes. Let me see if I can find anything.

Siliconguy, I suspect there’s going to be a lot of that. I wonder how long Keir Starmer will survive in Britain.

Tag, thanks for this! I have a copy of I Saw The World End — even though it’s incomplete, it’s utterly worth reading. He also did an audio discussion, which I have on CD — An Introduction to Der Ring des Nibelungen — which is equally worth your while.

Blue Sun, that’s quite true. What’s more, there’s a sense in which that’s implied by the conclusion of the story ahead of us.

Ron, thank you. I love the history of ideas, and since it’s not being practiced much in a form relevant to ordinary people these days, I figured I might as well cut loose and provide an example of what I think the field ought to be doing. As for earned power, that’s very simple. Power is earned when it’s freely granted by the people over whom it’s exercised. Think of a guru and his chelas — they give him considerable authority over their lives, because they recognize his attainment and want to emulate it. In the same way, a successful warlord gains earned power because his warriors know that he’s led them to victory before and will do it again. The people who crave unearned power want to control people without doing anything to encourage them to cooperate — they want to get loyalty but aren’t willing to give it, and they demand respect while doing nothing to earn it.

Patricia O, thank you!

Slithy, that’s occurred to me more than once.

Inna, thanks for this! I wonder how many other people were motivated to go to the polls by Peanut’s fate. As for the squirrel on the stage, the Daily Fail was one of many sites that carried the video:

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/video/news/video-3307615/Video-Squirrel-runs-stage-Kamalas-concession-speech.html

Polecat, thank you.

Jessica, hmm! I need to learn more about that. Can you point me to some sources?

Mary, thanks for this. My late wife was a great fan of Gaskell.

Wotan’s plan – to encourage rebellion against the existing order of society, in the hope of snatching power from the hands of the rebels once they seize it – was basically my plan all throughout undergrad. What’s also funny is the triggering event that made me began to lose faith in that plan is something you also mention in this essay.

I firmly believed that it was possible to design a better society from scratch. What irrevocably shook my faith in this belief is my part-time job in undergrad working at top class cognitive psychology lab. Without looking for it, we found explicit evidence for differences in reaction times between people of different races, which is significantly correlated with IQ and working memory, and is also something that is thought to be mostly due to genetics rather than something that is due to societal or environmental indicators. When I brought this up at our weekly lab meeting, that race was our single biggest confounder outside of piano playing or video game playing, I was told explicitly to ignore it.

So what ends up happening is I ignore it, but start reading more on the IQ literature, and I would started telling my intellectual circles that I don’t think our plans to bring about a more equal, better society would be effective because a lot of the outcomes are influenced by genetics rather than by societal forces, and we need to acknowledge that. That view got me disinvited from all of my intellectual circles, even as I still clung to the progressive dream arguing that the proper response is to recognize that if innate differences in IQ exist, the best way to achieve equality in society is to compensate by taking from the more highly paid, higher skilled workforce and distributing that to the lower paid, lower skilled workforce. My logic was since that that which enables high skilled people to be high skilled (IQ) has a strong unearned (genetic) component, it’s unfair to reward people based on that and pretend that it’s due mostly to hard work or teachable behaviors.

And, once that argument was firmly rejected by everyone in my intellectual circles (looking back at it, probably because I was threatening their rice bowls, their egos, and their politically correct sensibilities at the same time), I was left alone with the knowledge that a lot of people’s life outcomes are determined by genetic forces entirely outside the influence of society, and that fixing society isn’t going to fix that. Thus, if the goal is a utopia of equality, that seems impossible to design in a world where human beings aren’t blank slates upon which we can impose our will and vision.

Then, visiting Cambodia a year after that made me realize that that goal is not only impractical, but evil.

Adding to this, now, nearly 20 years later, I’m in a strange spot where I did the usual trade, principals for money trade with the idea that once I had enough money I could somehow better the world, and I’m finding that there is no way to “evade the ghastly consequences of capitalist commodification.” As soon as you reach for the ring, it has you, and there’s no real way to walk away from it without losing everything you obtained from it, and whatever goal you had for the betterment of the world or whatever, forget about it, because your goals are subsumed.

I got a lot of this essay! Thanks for this.

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May baby Gigi, who may be suffering from side effects of medication prescribed during pregnancy, be healed, strengthened and blessed. May her big brother Francis also be blessed and remain in excellent health.

May May Jennifer and Josiah, their daughter Joanna, and their unborn daughter be protected from all harmful and malicious influences, and may any connection to malign entities or hostile thought forms or projections be broken and their influence banished.

May Ram, who is facing major challenges both legal and emotional with a divorce and child custody dispute, be blessed with the clarity of thought, positive energy, and the inner strength to continue to improve the situation.

May FJay peacefully birth a healthy baby at home with her loved ones. May her postpartum period be restful and full of love and support. May her older child feel surrounded by her love as he adapts to life as a big brother and may her marriage be strengthened during this time.

May Hal Freeman’s daughter Marina recover from walking pneumonia.

May Leonardo Johann from Bremen in Germany, who was

born prematurely two months early, come home safe and sound.

May all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricanes Helene and Milton be blessed, comforted, and healed.

May Kevin, his sister Cynthia, and their elderly mother Dianne have a positive change in their fortunes which allows them to find affordable housing and a better life.

May Tyler’s partner Monika and newborn baby Isabella both be blessed with good health.

May The Dilettante Polymath’s eye heal and vision return quickly and permanantly, and may both his retinas stay attached.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

This is a really fascinating analysis of The Nibelung’s Ring – will have to save it for when I see it. I do have to disagree with the comments related to the 2024 Election aftermath. While Trump clearly had a bigger media megaphone, it seemed to me that Harris and the Ds put up, and have put up, policies that effectively distinguish them from the GOP, including on issues such as Housing, Education (and student loans), and Climate change. She, and they, may not be as effective at communication and media outreach, but that is not the same as saying there were no policies put forth.

Hi JMG (and friends),

I’ve been enjoying the posts on the Ring Cycle, but I do have one question. In this series, we’ve focused mostly on the libretto of the work (and to be fair, that is where is the meat of the story is). Is there any resources/texts dedicated to the music aspect of the Ring cycle, which a person whose a complete novice when it comes to the Western musical tradition could understand?

I didn’t know about those socio-political references back when i was reading ” The well at the world’s end”. However, i remember that both The Dry Tree and The Lady of the Abundance had a lot of unexplained things around them, as if the reader was already expected to know a lot about them. Now i see why.

Can you explain a bit more about what each of these two stand for in Morris political view?

@Mary B #38

Mary, I didn’t mean myth in the sense of a story that is completely untrue. The factual part is the change that’s already underway. The “mythical” part is that since we humans are observant enough to identify this change, ergo, we are omniscient enough to know how exactly it will play out, and omnipotent enough to stop or reverse it.

Hello JMG and kommentariat…thank you John, for this interesting and wise relief; current affairs like Spain floods and Trump can wait…

Really enjoying this series of posts.

Not sure if you have access to X (aka Twitter) but this clip reminds me of the hypocrisy of those who want to undermine the system that supports them:

https://x.com/kpac_15/status/1726340402809344277

Possibly not many of the protestors themselves are Wotans – more the ignorant footsoldiers, perhaps? Just wondering if you had anyone in particular in mind, prominent in the public eye, who is currently “doing a Wotan”?

Hello again, sorry just realised I hadn’t added any context to the clip I posted.

It was filmed at a “Just Stop Oil” protest on London, where the protestors think the best way to “stop oil” is to block traffic, reducing London to gridlock, so that nobody (including ambulances) can get anywhere.

And as their detractor points out, they haven’t really thought this through. “What are your clothes made out of?”

“Those of us who are enticed by the intellectual life need to understand that it’s basically a hobby; like most hobbies — say, knitting — it has its productive side, and it’s possible to put it to good use in its own context, but Pythagoras and all his heirs were and are dead wrong when they convinced themselves that intellectual achievement is the same thing as practical wisdom. I would argue, in fact, that intellectuals of all people are very nearly uniquely unsuited for political office, and should content themselves with the indirect power they can have by putting interesting ideas into circulation.”

Very interesting. I’m reading The Razor’s Edge by Somerset Maugham this week -and loving it. The argument / conversation between Larry and Isabel when they break off their engagement, speaks to this tension between practical wisdom and intellectual wisdom.

This line of thought has got me thinking about monasticism again. The monks of the past preserved some of our heritage and may do so again. It would be interesting to see some kind of monasticism ala the province of Castalia in our future. My point is, that I think some kind of monasticism will be one avenue for the intellectual (again) in the coming ages. To tie this back to Maugham, the character Larry has learned to live on much less than his immediate peers, much to their consternation, and instead has enriched himself by the life of the mind. Can’t wait to see where the rest of it goes…

I guess it shouldn’t be a surprise that in my OPW meditation this morning I mused on the influence of three books on my life: 777 by Crowley, The Glass Bead Game and Godel, Escher, Bach. The last I haven’t even read yet, but it is coming up soon. How they influenced me is that I was told by people that in the case of 777, I would never understand it. This was when I was looking at in a Waldenbooks (yes, quite awhile ago!) when I was in 6th or seventh grade. I determined that yes, I would understand it.

Later, a girlfriend I had for a short while complained to me about no one ever understanding The Glass Bead Game or Godel, Escher, Bach. She didn’t claim to understand them herself, but she disparaged those who did. I’ve never been good at math, so have put off the last one, but I read Glass Bead Game immediately after this conversation with her, and it became important to me. This was around 2001 or 2002.

Looking up Godel, Escher, Bach at work in the catalog I get shivers of synchronicity: 777 pages. Same on the wikipedia page. That is significant, not because of Crowley who I grew bored with some time ago, but about the whole idea of correspondences.

That sense of proving others wrong, I feel a little less forcefully than I did when I was younger -the feeling that drove me to pursue things which others said were a waste of time, or would never bear fruition. But it is still there, tempered. The sense of will towards something, in the face of opposition… it’s been a wild ride so far. But I’ve needed quite a bit of help from people who have more practical wisdom than me for such things as fixing cars, handyman knowhow needed for owning a house (which I’ve gotten better at, but still no super talent or inclination for) , and just feeling capable with practical things. I don’t think I could have not been interested in books, music and such. The challenge has been to balance it with my practical responsibilities in the world and find healthy outlets for my inclination.

Thank you again for these essays. It’s enriching my understanding of Tolkien as much as it is of opera, and giving me an appreciation for how the ideas from these works have influenced culture so forcefully by their circulation.

Thank you, JGM. I do agree “not fit for command” may be a better way to contextualize the intellectual issue. Though I would argue that, while Wotan seams like a good match for the intelligentsia as a group, individual members act more like Siegmund. Please bear with me.

Oh, Wotan did a number on this guy. Raised as an outlaw in the woods, the boy never learned the ways of his fellow men. If anything, his moral code (and I do think he has one) is in direct conflict with the established order and the social contract he is nonetheless expected to uphold. So, when he returns to the World after loosing his father, he finds troubles wherever he goes. Those are troubles of his own making but he is oblivious to that fact; he just calls it “misfortune”. His frustration turns into resentment, and he boiling in this own juice he has been until he becomes an outlaw in his own right: he responds to the call of a supposed damsel in distress and ends up a murderer, even causing the death of the woman he had set out to aid in the first place.

From this, I compare to the rite of passage that many of us had to go through in this civilization, but which seams to be hitting Gen Z much harder than usual. We where raised to thrive in a world that never existed, and the first task to complete as a young adult is to pick up the debris of our crash with reality and build up a live for ourselves out of it. As a token sample of what I mean, I will ask the commentariat when was the last time you needed the Periodic Table for anything (I know some of you do, but there are hundreds of other useless facts you where forced to learn in your formative years; Chemistry just was my own pet peeve).

I am thinking the time when the young heroes go Wotan is when it seems that some Giant is going to take away something that is Precious to them (more often than not, the possibility of manifesting some cherished idea). They could pick another, better, idea to give it a try. Instead, they decide they have had enough of this injustice and they’ll just cheat their way to success.

“The result was an uprising in which most of the students of Pythagoras were trapped inside the building where they met, and died when it was burnt to the ground. Pythagoras himself escaped, but died a short time later in the neighboring city of Metapontum, his dreams of a utopia of wisdom shattered.”

A hard lesson for philosopher-kings wannabes…in every time, including our time.

Apologies if this has already been mentioned, but I find it wryly amusing that intellectuals as a class seem to be spectacularly bad at learning the obvious. Supporting a rebellion in order to try to grasp power from the rebels seems like a bad idea just from a common sense perspective (what happens if they actually win, and take away the positions and stability that most intellectuals depend on?), and it has blown up so many times: among many others, the Terror of the French Revolution, which saw many of the people who supported it for ideological reasons losing their heads in a very literal fashion….

“Peanut, thou art avenged!”

I saw the video. I suspect a political dirty trick — a good one, though!

JMG,

Would you say that Pythagoras’ introduction of abstract law and mathematics gave precedence to Elemental Air over the other Elements? It seems like a balance of Elements was always the best way to go, and you can see the desire for that balance in many systems. This imbalance in Air might be the reason why we romanticize Earth. If I remember correctly, Air and Earth are polar opposites.

Oh no, and now we’re heading into a series of Great Conjunctions in Air for the next 200 years.

You seem to be doing a very poor job of driving off your readers with this series! Question: who are the Valkyries in your/Wagner’s scheme? They’re the result of a union between Wotan (intellectuals) and Erda (Nature?) and have the job of recruiting warriors (from the proletariat?) for Wotan’s army. Brunnhilde in particular is a favorite of Wotan’s, but she turns against him and saves Sieglinde (and ultimately the universe, in Gotterdamerung, but we’re nowhere near there yet). What group/class do they represent?

When I’ve read about “Traditionalist socialism”, I smiled. I can’t avoid to remember another strange ideology mix. I’d like to remind you that Salvador Dali classiffied himself as “a Monarchist and an Anarchist”. He was proud of it. However, I don’t know if Morris would be happy of being described as a Traditionalist Socialist. Well, I’d be according this strange political mix, maybe a Conservative Socialist. Maybe I’m kidding, maybe not…

Dennis Michael Sawyers , Benedict of Nursia and Francis of Assisi were two men born into “good families”, i.e., what we nowadays call privilege, who did walk way, firmly turn their backs on, the gold ring.

Mike Bressler, the policies put out were more tired neoliberalism. Tax credit when what is needed is actual price controls; no investment in mass transit to get people out of their cars and to work, combined with ritual kowtows to Isreal. I am increasingly convinced that the Dems. threw this one. They were going to lose anyway; the Biden admin was effectively over after he failed to support striking railroad workers, but it didn’t have to be this bad.

@C.R. Patino – thanks for the comment on Siegfried’s upbringing and its ties to today’s kids. You can have a primitive code of honor that plays very poorly in a world of law-based civilization, and vice versa, and you see it sometimes in Irish legends such as Cuchulain’s. BTW, the lore – the Eddas, and the similar works from Germany and Scandinavia – makes it perfectly clear that Odin is a world-class A-1 ratfink, and that’s openly acknowledged. He’s the god of sorcery and dirty tricks a well as the unceasing quest for knowledge. Thor was the god most focused on in the days when Christianity v. the way of the old gods was an ongoing battle, and Thor’s hammer was the usual emblem. People said “I am a friend of Thor,” but very rarely, if ever (I can’t remember a single case) “a’ friend’ of Odin. Worshiper, yes.

About today’s Gen-Z kids, something that I, as grandmother and great-aunt to mine, have given a lot of thought to. Looking at the calendar, they have never known a world that was not in crisis, any more than my contemporaries did. Whose parents gave them to think it was dangerous out there. Who, if a grandparent slipped them money for their deepest desires – freedom money – spent it mostly on things their parents approved of. But unlike the last one, the crisis we’re in has never come to a head – unlike the one their great-grandparents knew – but very, very like the the time after the Civil War. Those young people ended up settling the West, which was probably their salvation; that’s an option closed these days.

Siegfried they’re not. But the obedient Valkyries?

Anyway, that’s my $0.02. Except that, having had a chance to read today’s election results, we won’t be seeing Wotan running things for a while. It’ll be Thor’s hammer time.

Dennis, it’s a very common delusion. Kudos to you for seeing through it.

Quin, thank you for this as always.

Mike, I think you misunderstood what I was saying. It’s not a matter of policies, it’s a matter of visions. Did Harris present a vision of the future as something other than a continuation of a miserably unsatisfying present? Did her policies offer any substantive reason to think that the next four years would be any different from the last four? I’d say “no” on both counts, and that’s what cost her the election.

Hobbyist, if there is, I don’t know about them. Anyone else?

Guillem, I think I explained the political meaning of the Dry Tree (scientific materialism) and the Fellowship of the Dry Tree (Marxist socialism, with its scientific-materialist veneer) clearly above. The Lady of Abundance is art — all the arts, taken together as an allegorical person. Remember that Ralph is Morris’s surrogate here; after his run-in with the world of capitalist business and commerce (the Burg of the Four Friths), he becomes a full-time artist (falls in love with the Lady of Abundance) before other events finally send him on his quest for the source of life and spirit (the Well).

Chuaquin, you’re welcome.

Sydaway, take your pick of the celebrities, media intellectuals, and pundits who claim to be against climate change, imperialism, et al. and yet profit from the system that includes these things and won’t do a thing to interfere with the gravy train. There are your Wotans.

Justin, I’m quite sure that monasticism will have many a heyday in the centuries ahead. As for Godel, Escher, Bach, hmm — thanks for the reminder. I haven’t read it in forty years, and I wonder what I’ll think of it when I reread it.

CR, good! Yes, exactly — remember that in Wagner’s mythos, human characters are classes or groups of human beings, while gods and giants are the abstract ideals that humans aspire to and represent. Siegmund as rebel without a clue is a very familiar type to most of us.

Chuaquin, and one they seem almost uniquely unwilling to learn.

Taylor, I know! You’d think they’d get a clue, right?

Phutatorius, if it was a deliberate trick, kudos to the trickster!

Jon, that’s one way to think of it, yes.

Roldy, the Valkyries are abstract ideals. Brunnhilde is the one who’s clearly identified by Wagner’s mythos: she’s the ideal of liberty. We’ll see how that plays out in the operas to come.

Chuaquin, I always thought that Dali’s comment was very sensible. He wants a king who reigns but does not rule — who serves as a screen onto which people project their need for a daddy figure, but who expresses that in purely ritual form. I don’t think it would work in practice, but it’s a charming idea.

Maybe that crayfish is a lobster.

“Consider the Lobster” is what Dr. Jordan Peterson (borrowing from late author David Foster Wallace) entitled his chapter on how the serotonergic system in human physiology has been conserved by nature since at least our last common ancestor with crustaceans, and so consequently we’re more constrained in our options around hierarchies, human potential, etc., than we’d like to believe. His background in Jungian analytical psychology, existentialism, and phenomenology also reflects something similar to what I’ve gleaned from your teachings, which is that, in spite of — and possibly because of — those constraints, we actually have more of a different kind of potential than we realize.

A little tangential to the article, but a data point related to the election and some comments made about it above, feel free to delete this if it is too off-topic.

NBC News of all outlets wrote an article where they anonymously interview several Democratic Party insiders immediately after the election. Much of what is said is deeply critical of current leadership, and indicates that many insiders knew exactly what was wrong with Harris’s campaign but, in short, they weren’t listened to:

https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/shattered-democrats-grapple-kamala-harris-loss-rcna178967

Personally I don’t find this surprising at all. Some especially interesting excerpts:

“They said they see a party that drifted far from its onetime identity as the protectors of those left behind, to represent the party elites. They questioned the campaign’s decision to focus on reaching out to “soft” Republicans when they had their own issues with base voters.

Some spoke of revamping the party’s outlook on immigration, calling for stricter enforcement on the border. They saw the rising support for Trump in metro areas as a backlash from early policies during President Joe Biden’s administration that enabled migrants to flood into blue states, where they were often housed and financially supported even as working-class residents struggled to receive services.”

“Harris, they said, inherited a campaign where the fundamental negatives of a nation on the wrong track were baked in. Some blamed the influence of the Obama-era consultants and strategists who play an outsize role in messaging and who, according to one longtime Democrat close to the Biden team, were “stuck in 2009.””

“Campaign aides and allies directed much of the angst at the campaign’s chair, Jen O’Malley Dillon, whom they complained ran a shop with the hand of an autocrat. According to three senior campaign officials, they saw her as loyal to Biden, never allowing Harris to truly make the break from him that she needed to win.

O’Malley Dillon, they said, siloed off information with just a tight circle of advisers, keeping other senior officials off email chains and updates. That sidelined many of the aides who knew Harris the longest — and the best, they said.”

And finally,

“The aide believed Democrats would still have lost if Biden was the candidate and that the party should have worked to ensure Biden didn’t run for re-election.

“How the hell did we not deal with this problem? He’s 80 years old. He was supposed to be a one-termer. The man could barely speak and actually be coherent,” the person said. “It was too late, and we knew we had a Biden problem this time last year. The party knew it and people truly were not honest about how out of touch he was and how his age was really playing with America.”

Ultimately, a Democratic lawmaker said, the party needs to reassess its leadership both in office and behind the scenes.”

Of course, it’s yet to be seen whether any of this will translate to a real change in the party’s leadership. I guess we will have to wait and see.

Hi JMG,

I’m enjoying these essays on Wagner’s Nibelung’s Ring; is there any chance you could collate and publish them in book format? Would be a great read.

Writing Hobbyist @43: I checked out Roger Scruton’s book “The Ring of Truth” a while ago. It had summaries of the operas and quite a bit of music theory. But for a complete musical novice? Not really. You’d want to pick up a familiarity with the piano keyboard and basic music theory to get much out of it. He gives hundreds of examples, but you’d need to be able to read music.

Chaquin, JMG, re the Monarchy.

I think you could make an argument that the British monarchy gets pretty close to that. They have a moat ritualistic ceremonial role and and there is a lot of projection of the hopes and fears put upon them

MCB

JMG,

Indeed, you have explained what both the Felloship and the dry tree in itself stand for, but what i was wondering is that, if the Fraternity is Marxism Socialism and the Lady stands for Art, then why the Champions of the Dry tree are also in love with the Lady?

Also, one of the things that struck me back then about the lady was how she seemed to stirre trouble wherever she went; Every powerful man around fell in love with her and was decided to obtain her no matter the cost… What side of Art is in display here?

I Hope this does not veer too much from the theme, however.

Thanks,

Guillem.

OK John, indeed Dali had a good idea when he mixed Anarchism/Communism and Monarchy…the problem with this great artist was that you never know when he was kidding and when he was speaking seriously.

JMG and @Phutatorius #53,