Let’s take a moment to review our story so far. In mythic terms, it’s a straightforward fairy tale: the gold from the bottom of the Rhine, stolen by the dwarf Alberich and turned into a magic ring, was then stolen from him in turn by the god Wotan, who then had to hand it over to the giants Fasolt and Fafner under threat of imminent doom. Fafner killed Fasolt on the spot, made off with the ring and the rest of the dwarf’s treasure, and turned himself into a dragon, the better to guard the treasure. Wotan, armed with all the grubby tricks available to him as king of the gods and supreme sleazeball of the Wagnerian universe, wants the ring back, but he can’t break the agreements he’s made without losing his power; Alberich wants the ring back, too, but he doesn’t have the guts or the physical strength to face a dragon; and the Rhinemaidens, the spirits of nature who originally had the gold, also want it back but are powerless to get it.

It all seems very cute and harmless until you realize what Richard Wagner was actually saying with all this symbolism, using the philosophy of Ludwig Feuerbach as a mask. The gold from the Rhine is the wealth of nature—all of it, of every kind, defining “wealth” here as anything that human beings value. The making of the Ring is the process of commodification through which, all of human life got flattened out to fit a one-dimensional scale denominated in money. Alberich here represents the productive classes, those who actually convert labor and raw materials into tangible wealth; Wotan represents the intelligentsia, which craves control over the commodification process as part of the lust for unearned power that pervades Western intellectual life; the giants represent the political and economic ruling classes, which the intelligentsia have to placate in order to keep their ample salaries and their status in society.

That is to say, the world of The Nibelung’s Ring is the world we live in today. Not much has changed in our basic situation, all things considered, since Wagner’s time. The plot of The Valkyrie, the second opera in the cycle, is another matter. Let’s go through the symbolic narrative first, and then talk about what it all means. Here as before, if you haven’t downloaded and read the libretto for The Valkyrie, do that now before going on; you can find it here.

We begin with Siegmund fleeing through the storm. As usual, he’s in danger of his life, and as usual, the reason is a disastrous mismatch between the abstract ideals he believes in and the realities that surround him. The mismatch isn’t accidental; his father, though Siegmund doesn’t know this, is Wotan, and the king of the gods has set the whole situation up as part of his plot to get the ring back. There’s a whole cascade of ironies here; Siegmund thinks he’s a free man trying to do what’s right in a world out of joint, but he’s actually just a tool in a disreputable scheme to extract stolen goods from one thief for the benefit of another.

So he comes stumbling into the hall of Hunding, exhausted and weaponless, and the first person he meets is Hunding’s wife Sieglinde—“wife” here being a euphemism for marital slave, since she was kidnapped and sold to Hunding by raiders. Siegmund and Sieglinde are brother and sister, though they’ve been separated long enough that they don’t realize that until later on. The hall in which they meet just happens to be the one where a mysterious figure showed up at Hunding’s marriage feast and thrust a sword into the giant ash tree that just happens to grow up through the middle of the hall. Once again, we see Wotan’s meddling fingers at work.

The rest of Act I plays out like clockwork. Hunding arrives; it turns out that he was among those hunting for Siegmund, but the old Germanic tribal laws of hospitality forbid him from slaughtering Siegmund there and then. He grants the young man shelter for the night but warns him that they will fight to the death the next morning. He then goes off to bed with Sieglinde. She appears a little later, having put a drug into Hunding’s nightcap that has him out cold, and the inevitable romance occurs. Strengthened by love and renewed hope, Siegmund draws the great sword from the tree, so he’s prepared to fight Hunding; the two of them recognize each other as brother and sister, and off they go to a night of love.

That probably deserves a comment of its own. Brother-sister incest was a pervasive theme in 19th century European literature, more often hinted at than introduced as literally as Wagner did, but much less shocking in his time than it is in ours. The reason is quite simple: the social rules of the 19th century only permitted young men and women to have unsupervised access to each other if they were closely related. That meant that even when actual incest didn’t take place, young people routinely felt their first sexual reactions toward siblings—and the resulting guilt, amplified by endless sermons, played a massive role in the psychology of the age.

What made Freud shocking, in other words, wasn’t that he talked about incest. It’s that he introduced Mom into the picture, and didn’t stash it safely away in a work of art, as something that could be held at a safe distance behind the proscenium of an opera house. He pointed to the role of incest fantasies in the individual psychology of respectable people, as part of his general demolition of Victorian sexual hypocrisy. We still haven’t finished processing that very sudden shift, and the vagaries of our collective attitudes toward sex are driven in large part by the shockwaves—but that’s a discussion for another time.

As Act II begins, we’ll leave Siegmund and Sieglinde as much privacy as an opera allows, and we’re back with Wotan, who’s plotting with his favorite daughter, Brunnhilde the Valkyrie. This is where the audience (if they haven’t read the libretto in advance, that is) find out all about his scheming. It’s a fine bit of dramatic contrast—we’ve just seen the whole thing from Siegmund’s viewpoint as sympathetic hero, and then Wagner shows you the seamy side of the same fabric. Wotan’s in trouble, though, because the audience isn’t the only one who sees through him. So does his wife Fricka, the goddess of social custom and collective consciousness.

This spells instant disaster to Wotan’s plans. The whole point of all the gimmickry he’s set in motion is to give him plausible deniability in his attempt to regain the ring: if it’s clear to everyone that the whole thing is a stage play Wotan set in motion, he loses that, and with it the contracts that give him his power. Faced with Fricka’s furious condemnation, all Wotan can do is crumple and leave his puppet Siegmund to his fate. Since self-sacrifice is the one thing he can’t imagine doing, he has no other choice.

This is where things get complicated, though, because he’s not the only player in the game. Brunnhilde is also involved. Unlike her father, she’s honest and, as we’ll see, wholly capable of self-sacrifice. Wotan orders her to go tell Siegmund that he’s got to suck it up and die heroically. That’s her job, because the Valkyries are the ideals manufactured by the intellectual class in pursuit of its goals, and Brunnhilde is the ideal of liberty. It’s an authentic ideal, but it’s also a tool that intellectuals in the Western world have used ruthlessly in pursuit of power.

It’s when Brunnhilde confronts Siegmund that Wotan’s plan really runs off the rails, because Siegmund isn’t willing to follow blindly the role that Wotan has sketched out for him. Unlike Wotan, he cares for something other than his own ego: he cares for Sieglinde. For her sake, he proposes to ignore Wotan’s interests, kill Hunding, and go off with his sister-bride to whatever future awaits them. What’s more, he succeeds in getting Brunnhilde on his side. Translated from the Feuerbachian, he wrenches the ideal of liberty out of the hands of the intellectual class that promoted it and applies it in his own way, to his own very human interests.

As Wagner realized, but a great many intellectuals still haven’t figured out most of two centuries after his time, that’s the risk you run if you promote a high-sounding ideal but then insist that it can only mean what you want it to mean. It’s always possible that the people you’re trying to motivate through those slogans might apply them in ways you don’t intend. As I write this, our intellectual classes here in the United States are melting down for exactly this reason: having insisted that the ideal of equality can only be applied to races, genders, and sexual orientations, they were blindsided when millions of working class voters applied the same ideal to social classes, and insisted on treating their own interests as equal to those of their supposed betters. So far, at least, the response of the intellectual classes to this Siegmundian disobedience on the part of working class voters seems mostly to consist of blind rage.

Chalk up another one for Wagner, because that’s exactly how he has Wotan respond. The king of the gods explodes in a blind rage that could come straight off today’s corporate media, intervenes directly in the fight between Siegmund and Hunding, and shatters the sword he himself had given Siegmund so that Hunding can kill him. Brunnhilde flees with Sieglinde, who is carrying Siegmund’s child, and helps her get to safety in one of those deep forests that always feature in Germanic legends. (We’ll hear more about that forest as the story proceeds.) Then she confronts her enraged father. He rants and raves, but as his fury cools he starts to show one of the few glimpses of genuine sympathy he shows in the story. It doesn’t keep him from behaving like a jerk, but at least he has the good grace to feel bad about it.

So after the yelling and negotiating are over, he puts Brunnhilde into a magic sleep and, with the help of the fire god Loki, surrounds her with a wall of magic flame that only a fearless hero can pass through. Again, this is cute and harmless until you see through the Feuerbachian mask. What Wotan has done is to take the ideal of liberty and make it as unapproachable as possible. Sure, the intellectual classes say, liberty is a great ideal and a wonderful goal, let’s all praise it to the skies, but don’t any of you underlings dare try to do anything about enacting it in your own lives. At the same time—and this is one of the places where Wagner’s creative genius really shows—they know perfectly well that someday somebody will go straight through that wall of flame and awaken that ideal. They are terrified of that event, and they long for it.

In Wagner’s time, and in ours, they are and they do. Yet there’s something much more specific going on in this opera than the kind of general overview just laid out might suggest. It’s important to remember two crucial points here. The first is that in the grand scheme of Wagner’s opera cycle, The Valkyrie is set in the past—and that’s the past from Wagner’s perspective, not ours. The second is that the past as seen from mid-nineteenth century Europe was dominated to an astonishing degree by one event: the French Revolution.

From the walls of the Bastille

And through the streets of Paris

Runs a sense of the unreal…”

I’m far from sure anyone nowadays can even begin to understand just how vast a shadow the French Revolution cast over the century that followed it. Certainly those of us born and raised in America have less than no clue, unless we saturate ourselves in European history and then make a significant effort of the imagination. The impact of German National Socialism on the modern Western imagination is comparable in some ways—we still have people shrieking about Nazis almost eighty years after the inglorious collapse of the Twelve-Year Reich, after all—but that impact is mostly limited to the political sphere and a few areas of culture. The French Revolution left nothing untouched.

In retrospect, Europe should have seen it coming. England had a revolution of its own in 1641-1645, and finished it up by chopping off the head of King Charles I in 1649, but hushed it up afterwards in a very British sort of way and went around pretending that nothing much had happened. The American Revolution of 1775-1782 was more of a shock, since everyone knew that we’d cheerfully have chopped off the head of George III if he’d given us half a chance, but the aftermath turned out to be a great reassurance to conservatives everywhere: the new federal government left the elite classes of the colonies-turned-states in charge of their own backyards, and simply gave them a new arena for their interminable bickering. (That changed, granted but it took a long time and went through a whole series of intermediate stages, from the Jacksonian era of the 1820s to the Obama era that ended so abruptly last month.)

The French Revolution started out in this same moderate fashion. After decades of spectacular mismanagement, the French monarchy and aristocracy between them had driven the nation into effective bankruptcy through uncontrolled deficit spending. The aristocrats used this to back King Louis XVI into a corner and forced him to call elections for the États-Généraux, the rarely convened national legislature of France, which alone could enact new taxes. Their goal was to get him to restore some of the privileges his grandfather Louis XIV had taken from them in exchange for support on his tax proposals.

What neither they nor he realized was that the French electorate, like ours last month, had its own agenda in mind. The États-Généraux had three houses—the first for the aristocracy, the second for the Catholic clergy, and the third for ordinary French voters—and the latter took the elections as a referendum on the entire French system of government. By big majorities, they packed the third house with advocates of radical change. Once the États-Généraux convened, the third house simply voted to proclaim itself the National Assembly, invited sympathetic members of the aristocracy and clergy to leave the two higher houses and join them, and declared itself the legitimate government of France. The national bureaucracies and the military, sick of the inept and dysfunctional royal government, sided with them, and the transfer of power happened very nearly before anyone quite realized it.

None of that happened by accident. French intellectuals had been laboring to bring it about for most of a century. The philosophes of the Siècle des Lumières (“Age of Lights”), to use the self-glorifying label of theirs adopted by later historians, were motivated by the craving for unearned power that so often corrupts Western intelligentsias. They had devoted all their considerable talents to stripping the French monarchy—one of the oldest continuously functioning political institutions in all of Europe—of the traditional legitimacy it had long held in the eyes of the people it ruled. Their motivation was straightforward: they convinced themselves that if only the monarchy could be overthrown, power would fall into their hands, since they believed as a matter of course that they were the smartest people in the room.

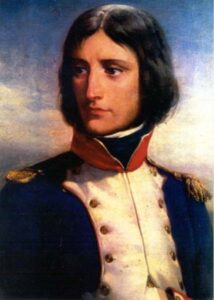

History shows how wrong they were. In times of crisis, power flows to men of action, not to intellectuals who only know how to deal in abstractions, and that’s what happened in France after 1789. Power passed from the National Assembly to ever more extreme and murderous factions, then to a series of fragile juntas, and finally to Napoleon Bonaparte, an ambitious army officer with a genius for tactics who seized power, proclaimed himself emperor, and plunged all of Europe into twenty years of war. By the time he was finally defeated once and for all and packed off to a barren island in the South Atlantic to live out a few dreary years of exile, France and Europe were changed forever, but not in the way that the philosophes had dreamed.

The behavior of the European intelligentsia during all these events bears close study. During the opening days of the French Revolution, the events in Paris were greeted by ecstatic cries in intellectual circles across Europe. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” the English poet William Wordsworth wrote in 1809, looking back on the enthusiasm of his younger days. Once the ruling classes of the rest of Europe realized the scale of the threat, though, that enthusiasm got muzzled in a hurry. The intellectual classes depended, as of course they still depend, on the support of the ruling classes for their wealth and influence. That was a leash that could be, and was, yanked good and hard if they got too far out of line.

Thus the intellectual classes found themselves in the same situation as Wotan, with their own machinations all too visibly on display and their plausible deniability in shreds. By and large—there were of course exceptions—they did the same thing that Wotan did: they turned on a dime, helped prop up the existing order of European society against the revolutionary impulses they had just been praising so exuberantly, and redefined the ideal of liberty into a distant abstraction. It was acceptable to exalt Napoleon himself into the pantheon of heroes, especially once he was safely out of the way, but the intelligentsia had to watch themselves very carefully for a while, as conservative forces across Europe did their level best to turn back the clock and reimpose the monarchical system the events of 1789 had fatally wounded.

Mind you, the intellectuals didn’t leave radical politics for long. By the 1830s they were back at it again, laying the foundations for the failed Europe-wide uprisings of 1848 and 1849; when those failed—well, the easiest way to describe it is to borrow JRR Tolkien’s phrase and note that always, after a defeat and a respite, the shadow of revolution took another shape and rose again. It’s interesting to note, too, that it didn’t matter in the least how many abuses were abolished and how many liberties granted, because the actual condition of the working classes or what have you was never much more than a excuse. Wotan’s craving for unearned power was the real force that set all the Siegmunds of Europe’s radical history on their foredoomed quests.

All these repetitions, though, have no place in The Ring. The nature of opera requires grand narratives to be compressed into a few vivid scenes, and so all those cycles of unrest stirred up by the intelligentsia appear in the opera once, in the form of Siegmund’s brief and tragic career. What interested Wagner was what would come next, now that the ideals launched into motion by the European intelligentsia had slipped decisively out of their grasp. That provided the central theme of the third opera in the sequence, where Siegfried—the child of Siegmund and Sieglinde—rises to his own brief, triumphant, and disastrous destiny.

Excellent post, JMG! I was looking forward to this!

The hardest part of the Valkyrie for me to understand is how Fricka can hold the Hunding-Sieglinde vow as sacred. All her other reasons and motivations are very reasonable, but that obviously coerced set of marital vows is weak grounds for her intervention – especially given that several of her statements are about how transparent and shallow Wotan’s plausible deniability scheme is. Is this just a plot convenience, or is there an additional Wagnerian commentary I’m missing?

Mr. JMG –

Thank you again for another great post! One of the magnificent aspects of this opera is the pacing of each act. In a line-by-line reading of the opera, no character indicates any of these great ideas to another character. Rather, these complex ideas are evoked over the course of each scene. I am impressed with the Wagner’s poetic ability.

One thing that I have been wondering as I have read this opera is whether I am missing out on some aspect of the performance. I understand much of the meaning of the opera can be gleaned from a close reading. I also understand there are visual and musical aspects of the opera. Commentariat, has anyone seen this opera performed live? What was the experience?

Hello JMG and kommentariat. It’s amazing to see Napoleon I entering Valhalla, I didn’t know that picture…By the way, I know you don’t like go to the cinema, but I went last year to see last Napoleon movie, and I didn’t like it much. John, you didn’t loose anything great…

This is very interesting, and certainly makes an interesting and plausible story. Do we have (direct or indirect) evidence that directly supports aspects of the interpretation, such as material from Wagner’s journals, letters, writings, and so on – especially with respect to the idea of Wotan as the intellectual class? I don’t ask this skeptically, I would just be interested to know about such evidence.

Greetings all,

Overall a rather pessimistic view of human nature and its inability to rise to any sort of ideals. The quest is bound to fail…

Sirustalcelion, that’s a measure of just how far Western ideas about marriage have changed since 1848, when the Seneca Falls convention launched feminism on its way. In Wagner’s time it was normal for young women to be coerced into marriage; under English law at the time, a woman was her father’s property until marriage and her husband’s property afterwards — until the abolition of slavery, she had exactly the same rights under the law as a slave — but she could be, and was, savagely punished if she broke the terms of a marriage contract that had been forced on her. That wasn’t true, interestingly, in the Middle Ages — women in feudal times could inherit and own property in their own right, and could rule a barony or a kingdom — but the 16th and 17th centuries saw the collapse of women’s legal rights across most of Europe. It’s an interesting detail of history that some American colonies and states allowed women to vote early on, but that right was eliminated by the 1820s and wasn’t regained for a century.

Mrdobner, of course you’re missing a huge amount by not taking in a performance. If you have the chance to attend a production of the Ring, I enthusiastically encourage you to do it — I’ve been to two cycles so far and I hope to do more.

Chuaquin, you didn’t lose anything by not knowing about Girodet’s painting, either. It’s pretty awful!

Michael, I encourage you to go back and read the earlier posts in the series, where I discuss the sources for this interpretation. Wagner explicitly identifies Wotan with “the intellect of the present day” in one of his letters, which I quote.

Karim, no, not at all! The mere fact that the intelligentsia of one rather peculiar civilization uses the manufacture of ideals as a tool for power-seeking doesn’t mean that all quests for the ideal are doomed — just that this one class, pursuing this one agenda, gets the results Wagner presents us.

JMG, If Trump represents a kind of soft revolution representing the working class and the entrepreneurial class then that of course portends a large recalibration for the intellectual class. If we assume that the intellectual class in the U.S. is primarily resident in academia and the media then that is where we should start seeing rapid change.

I would guess that the media will change most rapidly ( as it now seems to be doing) because the entrepreneurial class has the most direct levers of power over it. I expect the low hanging fruit in the mainstream media to be purchased on the cheap by Elon or others by money’d entrepreneurs and changed overnight. MSNBC say hello to your new bosses Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson.

But I think academia will be a tougher nut to crack as the levers of power there work more slowly. My personal opinion is that we will see a growing schism in academia between the hard sciences, engineering, ag. etc. and the arts favored by the intellectual class. The ” soft side” of the university establishment has had an outside influence on the campus climate. But the hiring and donating requirements of the new entrepreneurial class will require the ” useful” side to change more quickly and throw off the woke mind virus to have any hope of surviving.

This post got me reflecting on my own career.

As I have said before, I was (and am) your basic, “four-eyed”, Aspie, “walking encyclopedia” intellectual, from my childhood up.

I lived with my parents in Washington, D.C. and went to American University College of Public Affairs (which is basically the American equivalent to the French civil service academy). I might easily have become a member of “the Blob” myself, except for two things.

First, President carter froze Federal hiring at the start of his Presidency (just as I was close to graduating). So, I never got in to the Civil Service.

Second, I read Spengler at the age of 19 (followed by Toynbee at 21). Spengler did more than anyone to convince me that intellectuals have no place in positions of power, and cannot handle power safely or responsibly.

So, I “learned to code” (literally!) and spent 33 years in the IT industry, until my retirement.

Now, in the twilight of my life, I am a minor cleric in the Orthodox Church. Would Spengler have approved? Hard to say, but I am sure he would have expected it!

@JMG

Thanks for the answer. My mistake was thinking mostly about 21st century western civilization and the mythical dark age setting rather than 19th century cultural specificities. The immiseration of women as a class in early modern Europe was dreadful – a real theft of rheingold!

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Jennifer, whose pregnancy has entered its third trimester, have a safe and healthy pregnancy, may the delivery go smoothly, and may her baby be born healthy and blessed.

May Quin’s father Bob in Austin, whose aortic stent procedure went smoothly, heal quickly from the procedure, and may his health improve over the long term as a result.

May Charlie the cat, who has been extremely sick and vomiting but whose owners can’t afford an expensive vet visit, be blessed, protected, and healed.

May Scotlyn’s friend Fiona, who has been in hospital since early October with what is a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, be blessed and healed, and encouraged in ways that help her to maintain a positive mental and spiritual outlook.

May Annette have a successful resolution for her kidney stones, and a safe and easy surgery to remove the big one blocking her left kidney.

May Peter Evans in California, who has been diagnosed with colon cancer, be completely healed with ease, and make a rapid and total recovery.

May baby Gigi, who may be suffering from side effects of medication prescribed during pregnancy, be healed, strengthened and blessed. May her big brother Francis also be blessed and remain in excellent health.

May May Jennifer and Josiah, their daughter Joanna, and their unborn daughter be protected from all harmful and malicious influences, and may any connection to malign entities or hostile thought forms or projections be broken and their influence banished.

May Ram, who is facing major challenges both legal and emotional with a divorce and child custody dispute, be blessed with the clarity of thought, positive energy, and the inner strength to continue to improve the situation.

May FJay peacefully birth a healthy baby at home with her loved ones. May her postpartum period be restful and full of love and support. May her older child feel surrounded by her love as he adapts to life as a big brother and may her marriage be strengthened during this time.

May all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricanes Helene and Milton be blessed, comforted, and healed.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

I actually kinda like the idea of Napoleon soldier’s entering valhalla. After all wasn’t he some sort of frankish Wotan, leading his Wild Hunt of French, Poles and others throughout Europe? Though he used us and treated us as a tool we still like him….

“Brother-sister incest was a pervasive theme in 19th century European literature, more often hinted at than introduced as literally as Wagner did, but much less shocking in his time than it is in ours.”

So this is a very old topic in Western art…

Well, I’ve remembered this recent Swiss movie about brother-sister incest:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Brother,_My_Love

It’s curious that there’s nothing new under the sun, but we pretend we create something new every day to open a can of worms and “épater le bourgeois”.

“women in feudal times could inherit and own property in their own right, and could rule a barony or a kingdom — but the 16th and 17th centuries saw the collapse of women’s legal rights across most of Europe.”

John, that centuries (16th and 17th) are “casually” the same times of the cruel witch hunt across Western Europe. Were that inhumanous punishments against wise women a warning by “modern” governments against the “normal” women to be more submissive? Or…Am I seeing things?(where there wouldn’t be nothing related).

>but the 16th and 17th centuries saw the collapse of women’s legal rights across most of Europe

I wonder why they collapsed?

Mrdobner#2: It’s a pity, I haven’t seen this opera live never, only excerpts from youtube.

I wrote my master’s thesis on a lot of the subject matter Wagner runs through here, and I feel its worth noting that one thing about the aristocracy of the time is that when they look at the run of revolutions in their own time, they have something approximating our host’s diagnosis of the problem: the intelligentsia grasping for power and stirring up the public in order to get it. What’s interesting is that they feel that, for the most part, The People just want to be left alone to run their own lives and Metternich thinks that in the absence of pressure from the intellectuals they wouldn’t have done anything in the first place. Of course, Metternich is Metternich and his words on the matter should be taken with a grain of salt, so I think there’s something rather dragonlike about his sentiment. “If the people stay away from my den and just let me keep this ring, there don’t need to be any problems,” sounds good until you remember exactly what goes into creating a landed aristocracy in the first place.

The whole point of all the gimmickry he’s set in motion is to give him plausible deniability in his attempt to regain the ring: if it’s clear to everyone that the whole thing is a stage play Wotan set in motion, he loses that, and with it the contracts that give him his power.

I don’t think you could have planned the timing any better on this series. Our crowd of Dollar Store Wotans are still insisting that it’s not a stage play.

So this looks like the time to repeat the question I asked before you started: what happened to Loge? In Rheingold he’s a major player (and to my taste a very sympathetic character!). Here, Wotan calls on him to put the fire around Brunnhilde and it just appears – Loge doesn’t even put in an appearance. And then he’s gone. Is there any meaning to this?

Learned Sir,

Are there examples from non-Western civilizations where intellectuals also desire unearned power? I don’t know enough about, say, Confucian or Hindu philosophy to judge.

thank you,

Lothar von Hakelheber

Hi John Michael,

Thanks for the clear explanation as to where the characters fit into our current story. Sometimes, they’re all bad apples! 🙂

Ah, I see it’s that free will thing again. Doesn’t it make you want to sit the foolish Siegmund down and set him straight? Sure Arthur made some errors, but these characters and their antics are the entire next level…

They are terrified of that event, and they long for it. Is this a good example of what you contemplate, you imitate? Or do, they know deep down that they’ll have to face their worst fears? The ancient grand master of strategy, Sun Tzu, advised to never back an opponent into a corner. Such acts produce real world consequences, as we’ve (and the elites) perhaps learned today in the news. It’s rarely enough to say that you’re good, you actually have to embody good, whilst also being perceived as good – people can sniff out hypocrisy.

Eventually with all those shenanigans going on, the power of the ring will be diminished – and then where will all those characters be?

Cheers

Chris

Clay, the academic industry is vulnerable from a financial angle. If the incoming administration wants to clean house there in a big way, all it has to do is get the federal government out of the business of guaranteeing student loans, and change the law so that existing student loans can be discharged through ordinary bankruptcy. Once people who want to get student loans have to prove that they will be able to pay back the loan via a career, that’ll be the end of most of the ideological degree programs. It’ll also probably reduce the number of US universities by half, which will also help.

Michael M, I get the impression that a lot of us in the later part of the Boomer generation walked strange roads. I certainly did! It took me a little longer to get to Spengler, though.

Sirustalcelion, it was a very grim time in a lot of ways.

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Katylina, I suppose a case could be made for that!

Chuaquin, of course. As I recall, every sixty years or so somebody reinvents public masturbation as a form of “performance art,” and everyone forgets how many times it’s been rehashed before. As for the collapse of women’s rights and the witch persecutions, there may well be a connection.

Other Owen, it’s one effect of the pervasive “Islam envy” that spread through Europe while the Ottoman Empire was at its zenith. Notice just now much of Protestantism was an attempt to revise Christianity to look more like Islam, for another example.

Deoradhan, thanks for this! Is your thesis available anywhere online? As for the aristocracy, whether they were right or not, that does seem to be Wagner’s idea — and I’d suggest that it has some truth to it, though doubtless it’s not the complete truth.

Cliff, I’ve been watching that with some amusement.

Roldy, Loge is the independent intellect. In Wagner’s time, you saw less and less of that as politics elbowed independent thinking out of the way. If this reminds you of the present, why, I won’t argue.

Lothar, China’s the closest comparison, as the Confucian intellectual class spent more than two millennia convinces that it ought to run the empire because its members were the smartest guys in the room. The great difference is that Confucian philosophy is profoundly conservative in ethos, and so it was a lot easier for the giants to work out a modus vivendi with the gods; China’s Wotans wanted to keep everything stable, not to change everything.

Chris, what we might as well call the Wotan Syndrome — the tangled emotional state in which what a failing elite fears is also the subject of its most intense and secret longings — is a complicated thing. It’s partly a matter of imitating what you contemplate, but there’s much more to it than that. When you’ve wedged yourself into a lifestyle that you’ve been taught to want but you actually loathe, and you know at some level that you’ve cashed in all your ideals and turned your back on everything you once valued, the thought that somebody might bring your whole house of cards crashing down becomes at once your greatest fear and your greatest hope. We’ll see plenty of that as Wotan’s world continues to unravel.

JMG,

In re: ” it’s one effect of the pervasive “Islam envy” that spread through Europe while the Ottoman Empire was at its zenith. Notice just now much of Protestantism was an attempt to revise Christianity to look more like Islam, for another example.”

It wasn’t just Islam. In fact, I will say that it was not even primarily Islam.

Rather, I think it was Rabbinical Judaism. Notice how the Old Testament underwent a big revival in the 16th Century, with names like Abel, Sarah, Zachary, Joel, Joshua, Aaron, Jared, Ruth, Deborah, Isaac, etc. becoming much more popular than they were in the Middle Ages.

Many historians (particularly Sacvan Bercovich) have noted the Goethean “elective affinity” between New England Puritanism and Rabbinical Judaism. It was at about that time, that the role of the Virgin Mary began to be downplayed, with radical Protestants claiming that the veneration of Mary was “idolatry.”

The Protestant Reformation was quite explicitly misogynistic, and I think that such misogyny was an influence off rabbinical Judaism.

Yes, I know, anyone who questions the privileges and pretensions of AWFL’s (Affluent White Liberal Females) gets accused of “misogyny,” but there really is such a thing as hatred for women as such.

Once again I am in awe of your unique ability to present the lessons of history in ways we can relate to from where we are at currently. Very shareable–“You see, this is how human beings collectively react to the physical realities they by necessity confront, and which technology does very little to change. See the pattern repeating once again. Stand back and watch.”

About the loss of women’s rights – 16th and 17th centuries? I’d have thought, 17th and 18th. I know for a fact that after the American Revolution, in the early 1800s, before the Transcendentalists, there was what I’m sure was seen as a “cleanup” of some things that ha been tolerated before. For example, a harder line was drawn between the status of white indentured servants and African -descended slaves. And, yes, the liberties of women were cracked down on, too. As Abigail Adams said, prophetically, “Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could.” She had influence and agency; Quincy’s wife Louisa had far less. Now, in Britain, I’m not sure when the sweeping revision of the laws concerning women were passed, but I do remember it was considered to be a “reform.” A “setting things right.”

OT: In the 1940s, the ACLU defended the rights of Neo-Nazis to march through a Jewish suburb, they were that committed to free speech. Today, all I see in their literature is the pure Woke line. Likewise, the League of Women Voters used to be nonpartisan, so much so that they were the moderators for political debates up until the late 1980s. Now, they are so associated with the Woke Left that Republican candidates have refused to give them statements in the last several elections that I’m aware of, clear back at least to Obama. I have dropped my membership in both for that reason, a major reversal for me – I remember an old list of organizations I wanted to keep through the times ahead.; they’ve all been scratched off since -when? Certainly all this century. For what that’s worth.

As for women’s right and status and Wagner’s original source material: In the Nibelungenlied, a courtly German version of the tale, the maiden is essentially in purdah; many wives in in the Norse material were in Sieglinde’s position, but others are as free and active as Icelandic women generally were. (But then, Iceland was a frontier society. It’s no accident that the first state to allow women to vote was Wyoming.) Medieval wives were totally subject to their husbands by law, and daughters – like sons – could be and were married off as their fathers decreed, but a look at the records show that, say, a 15th century widow was a free as a man, and with as many responsibilities.

However, when those in power start thinking things are getting too sloppy, too free and easy, and crack down, women and peasants are the first to be reined in. A sorry fact of history.

JMG, I made the case a last week to someone last week that in 10 years 70% of the small private liberal arts colleges would be gone. In addition, I predicted that half the large state universities would be gone. This means that in most states outside of CA and TX there would only be one large public university left.

This particular person who went to a state university agreed about the private schools, but was totally aghast at the idea of only one public university per state. They were even willing to bet me $100 to be settled 10 years hence. The main reason they thought is it would be bad for traditional football rivalries. My guess is they had not thought much about the future of state budgets in the next decade.

Recently there was an episode of the Mel K show with author Richard Poe where he discussed the role of the British government in fomenting the French and Russian revolutions and then scapegoating the Jews. It might be just another attempt install the illusion of a guiding hand on a chaotic world so that reality doesn’t seem so intimidating, but I found it to be an interesting theory and was wondering if you had any thoughts on that.

Peter Abelard once said that he had a good mind to go and live in Spain because among the infidel he might be able to live a humble Christian life. Intellectuals tend to chafe at social conformism more than any other sorts of people. Bookish women simply can’t understand why they should waste reading time on fashion, cosmetics and hair styling; I have known intellectual, brilliant men who thought bathing a bother and nuisance. Some civilizations have kept such persons in institutions like monasteries and universities where they can be at hand when needed and left alone to pursue their researches at other times. I believe the proper role of such people in any society is to tell the truth as they see it, uninfluenced by fashion or the desire for popularity. No, Madam, you mustn’t build your guesthouse on that lovely bit of green because said green is a swamp which is 10 feet deep. Obviously, truth telling is a useful and necessary vocation, but truth tellers rarely have the judgement necessary for rulership.

Hello, JMG! I’ve been reading this blog for over a year now, and really like this series!

I read Spengler’s The Decline of the West a year ago because your sketch of his ideas seemed intringing. It weakened my faith in scientific materialism (since it isn’t “scientific” and yet its description of the Faustian soul resonates with me) and my political ideology (the passage on what he calls “Ethical Socialism” and how it really is about a lust for power).

About our society’s current Wotons, I read a blog post by a progressive the other day arguing for the cities– and just the cities– of the USA to secede and form their own union because conservatives are too intolerant.

Re incest: I recall reading that children reared in the communal nurseries of Israeli kibbutzim ended up feeling like siblings and therefore were not sexually attracted to one another and would frequently seek mates from neighboring kibbutzim. However, male and female children in a kibbutz were reared in much greater proximity than would have been allowed in 19th century Europe, sleeping in the same rooms and even showering together until 6th grade as the Israeli pioneers were dedicated to changing old roles and working for equality. Siblings in upper and middle-class families in 19th century Europe would have been in the nursery when very young and brothers and sisters close in age probably spent their waking hours together. But older children were educated separately: boys by a male tutor or at an all-male school, girls by a governess. In adolescence and until marriage brothers and sisters would have been able to walk in the garden, ride in a coach, sit in the parlor, play music, read aloud to the family or be read to, eat at the family table, and write to one another. Women of a family were also involved in nursing the ill or injured. Sisters as well as mothers would be sitting by a patient’s bed, administering medicines, wiping fevered brows (literally). I can see that this combination of a certain amount of intimacy with enough distance to allow idealization could lead to incest fantasies.

It looks to me like Biden was just putting on a show of wanting to forgive loans while knowing that the courts would likely reject the programs he proposed as outside his authority. Since he was involved as a senator in the writing of the current bankruptcy laws, he has to have known that a change in that law would have been an unassailable method to free borrowers. Somehow this option never seems to have been brought up. Of course, the entire subsidized loan program has been a huge giveaway to the banks–it doesn’t matter how much I owe; Citibank has been paid. And big bonus to the colleges as well, tuition rises to match loan limits.

Rita

A very interesting take on the Age of Revolutions! I do think the English Revolution, at least, had a considerable popular, even rural, bottom-up component, until the wealthier revolutionaries scurried back to the monarchy. But it was almost memory-holed. The 1830, 1848 and 1870 revolutions in Paris were also carried to an extent by small shop owners and artisans. However, their ramifications in Germany were much more strongly coloured by the educated classes – the German parliament elected in 1848 and convened in Frankfurt was known as “the professors’ parliament”. And that, after all, was where Wagner himself came into contact with revolution.

The loss of women’s rights from the 16th to the early 20th century surely has several reasons, and I would like to see “Islam envy” discussed at more length. Maybe it will still win a 5th Wednesday slot! However, I think urbanization itself also contributed. In Chinese history, nomadic invasions tended to give women more liberty, while the expulsion of the nomads confined them again. In the golden age of Pericles, Sophocles and Socrates, the wives of Athenian citizens were quite restricted in their movements, copying perhaps the cities of the Persian Empire, while rural Sparta gave them more rights. In the early Roman republic, women had personal names like Gaia and Lucia, while in later times, well-born Roman women were known in public only by their family names (think [Mrs.] Claudia). The early modern period was among other things a period of increased urbanization, too

Hi JMG and everyone,

Another great instalment JMG. Thank you!

I came across this recently, its sounds a bit ‘Wotanish” and sneaky to me, especially since the man’s family name isn’t actually this, but hey, It makes a great story!

He mustn’t have read Tolkien or Wagner…

“In my office in Jerusalem, there’s an ancient seal. It’s a signet ring of a Jewish official from the time of the Bible. The seal was found right next to the Western Wall, and it dates back 2,700 years, to the time of King Hezekiah. Now, there’s a name of the Jewish official inscribed on the ring in Hebrew. His name was Netanyahu.”

Regards,

Helen in Oz

ps it’s currently 38.2°C – not pleasant.

“After decades of spectacular mismanagement, the French monarchy and aristocracy between them had driven the nation into effective bankruptcy through uncontrolled deficit spending.”

That sounds oddly familiar. By no means is it limited to the French. I just checked and the US is $36 trillion, 170 billion in the hole.

Speaking of the French they are in an uproar again. No guillotines yet. The budget is blown and the government is broke.

“France’s government collapsed Wednesday following a vote of no confidence in the country’s prime minister, pushing the country’s political future into chaos and exacerbating its budgetary and looming economic crises.”

Michael, there’s been a sustained effort to downplay the immense cultural charisma the Ottoman Empire exercised over Europe while it was at its zenith. Very few people in Europe want to admit that Europe was a cold, grubby backwater at that time, contrasted with the rich, powerful, and cultured Ottoman sphere. Doubtless rabbinic Judaism also played a role, but the refocusing of Christianity from the sacraments to scripture was to my mind another reflection of Islam envy.

Patricia O, thank you, but this time it was really shooting fish in a barrel!

Patricia M, it was later in the US than in Europe — we always were behind the times.

Clay, I’ve occasionally thought about seeing if I could buy the campus of a failed liberal arts college one of these days and use it to establish some kind of Green Wizards’ institute. The way things are going, I’m far from sure that would be out of reach.

KVD, hmm. No, I haven’t seen that theory before and would have to research it before commenting. It seems unlikely, but we’ll see.

Mary, exactly. Intellectuals make good advisers to the powerful but they’re lousy leaders. If you want an archetype, think of Merlin, who was Arthur’s adviser and counselor, not a ruler in his own right.

Patrick, glad to hear you’re willing to open your mind. As for the cities, what a fine idea — I wonder what they’ll think when the rest of the country refuses to keep providing them with food, water, and raw materials…

Rita, yes, exactly on both counts.

Aldarion, every revolution has a large popular component, since intellectuals rarely want to do the fighting themselves! As for Islam envy as a 5th Wednesday theme, by all means bring it up when I next call for votes.

Helen, I’d wonder if the whole thing was cooked up for propaganda purposes.

Siliconguy, familiar indeed. As for the French, they haven’t had a proper revolution in too long. They need to stop being so lazy. 😉

JMG, would the distinction between this odius twisting of an ideal and ideals in general, correspond to the health of the grail quest and the failure of the Camelot project? Come to think of it, JFK is associated w Camelot…hmmm…by the way, other Owen and Michael Martin (too) Jacques ellul has an interesting chapter in The Subversion of Christianity on Islam’s effect on Europe, during the dark ages and medieval period. I’m not sure I agree w Spengler and the host in toto that the reformed period equates to the rise of Islam; the time scales are very different, for one thing. However I am certain there is a lot more there than generally acknowledged even in scholarly settings.

Lightbulb came on. Our elites are losing their shale: the first pseudomorphosis is over and lacking a connection to land, they get to choose between Islam, China or Russia. At least in their minds. Which not coincidentally are the three groups they are most hellbent on antagonizing, besides their own subjects of course, for the hat trick.

Sirustalcelion, JMG: The timing on the collapse of women’s rights in Europe suggests it was part of the same process symbolized by the forging of the Ring: just as Nature was transformed from someone to have a relationship with to a resource to be exploited, so too were women transformed from people into a productive resource to exploit. Does this sound plausible?

This is not meant as a rhetorical question, and not even necessarily a question anyone can answer, so much as we might have a conversation teasing out the implications, and never getting to the bottom of it.

But since the question of “unearned power” has come up, and the type of power in question is the power to rule over others (as opposed to the power to rule oneself, provide for oneself, and etc), it suggests that there IS some legitimate way to EARN the power to rule over others.

Personally, I struggle with this one, as, over a lifetime, I have become very firmly convinced that no one is BETTER at ruling a person than that person themselves. (Even when most people are bad at ruling themselves, almost anyone else would STILL be worse for any given particular person). However, I do see that there are public matters that need to be arranged and managed by more than one person so that all may benefit. I suspect that “earning” the power to so arrange and manage can never be more than a temporary thing before the power so earned is seen, and justified, as the power the earner is entitled to, and then things start to go downhill again, and round and round we go.

Still, I am very interested in your own thoughts, JMG, on how one may properly and legitimately earn the power to rule, and I am also very interested the thoughts of others on this question.

Thank you!

Hi John Michael,

That’s an interesting perspective, which is probably true. Hmm. I only bring this next matter up because of your observation, but I’ve spent a lot of time talking to different people randomly about their experience of the err, health matter over the past few years which seems to have sent a lot of people loopy. One of the most surprising admissions, and I’ve now heard it said often enough, was that people enjoyed the time immensely. And that stated opinion, differed so markedly to my own experience. I’ve been cogitating on what it all means ever since. Am I sensing an element of your observation as to the wanting someone to crash the edifice down, with what I’m hearing in that regard?

And yes, the historic French debt game is perhaps being played on a massive scale nowadays? As you’ve mentioned before, a difference in scale, is not a difference in kind. Now that’s another story I’m scratching my head wondering about. So strange that it would even be tried, given the historic evidence of how it generally works out, every single time.

Cheers

Chris

Very instructive. Very, very instructive.

In a recent comment you mentioned it would be better for intellectuals to feed ideas into society along the sidelines as it were. With regards to this installment, that makes a ton of sense. There really are better alternatives than trying to impose some kind of top down acceptance of a given ideal (all while failing to be an example of that ideal). We can get ideas into circulation without the kind of browbeating the current evangelical woke crowd uses to whip up saliva flecked invectives of aggressive resentful shame.

Stories are probably the best way to get them out there into the wild where they can feed the imagination of those who encounter them. Imagination > Culture > Politics

Do you have any thoughts on the transition between the current intelligentsia and the ones to come? I suppose we may be in a limbo for awhile. I see J.D. Vance and people who write at places like Unherd and County Highway as representatives of a nascent intelligentsia, coming into power with the entrepreneurial elite. The atheist woke will likely convert to Islam or join a convenient church, and some of the so-called intellectuals in that sphere will dissipate. As academia gets vulturized it will be interesting to see who and what sets up shop after its halls are vacated by the current tenured squatters.

The PCs and NPCs in the RPG of reality are changing alignments as the gods throw dice and move pieces across the board.

Remaining Lawful Neutral or True Neutral is difficult but I will continue to attempt a poise of equanimity amidst the Chaotic Good of the Changer swirling around us as the special snowflakes meltdown following the waning of the winter storm.

The assassination of the United Healthcare CEO also has overtones of the French Revolution, shaded with the slant of current crisis.

@JMG: Ah. Dion Fortune said, I think it was in Goat-Foot God, that “In any time, the intelligentsia is a generation ahead of their fellow Londoners,, who are a generation of the provinces, which are a generation ahead of the countryside, which in turn are a generation ahead of the really remote areas.” (i.e. – for Americans – “The backwoods”; for Australians, “the Outback.”) so that in any period you have that spectrum of public opinion. And of course, w.r.t. Europe, the most sophisticated American would have been a real hick from the sticks. Thanks for that elucidation.

Even today, someone born and bred British would have had a totally different definition of “civilized” than the high desert Westerners I spent 50 colorful years among. (Well, all right, in the state which was at the heart of MexAmerica-North-of the-Rio Grande. But the Anglo population was pure Mountain-and-Basin Western.) .

North-Central Florida is very close to being Georgia Cracker Dixie.

With regards to incest the novels of V.C. Andrews, TM, were very popular back in the day and still have a following. I guess that is part of the still unfolding working out of changes. There is a lot of lag time with these things when studying the historical influence of ideas.

I’m going to suggest another factor in the whole “Islam envy” issue and that’s the superior usefulness of an Islamized/Old Testament-focused Christianity to the colonial project. From the beginning, the leadership noticed that morale tended to be low among soldiers stationed in places where there was no town for them to visit for entertainment (such as the North Atlantic coast of North America with its tall trees, an enormously valuable military resource when battleships were made of wood) so getting those places settled had to be a high priority if the colonizing nation hoped to hang onto them. Maximizing the birth rate, genociding foreign peoples in order to take over their lands, a hierarchical authoritarian family structure with a certain amount of normalized domestic violence so that young men came out army-ready, all were part of optimizing the culture for expansion through conquest.

>That sounds oddly familiar. By no means is it limited to the French. I just checked and the US is $36 trillion, 170 billion in the hole.

That’s not what concerns me. What concerns me is the GROWTH of the interest on the debt. It has gone hockeystick. If this was a plane, it would be saying things like “sink rate” and “terrain” and “pull up”. But the people in charge are out to lunch. Nobody is flying the plane!

I guess we all put our heads between our legs and kiss something goodbye?

Re: Ottomans

The cultural pull of the Ottomans was that great?

I find it interesting these things go in cycles. Makes me think 2200 could see a surge in Islam again. Definitely all those little countries in the Levant have a tendency of getting rolled up into one empire or another. I’ve been maintaining the future belongs to those still willing to have kids, which pencils out to the Amish and the Muslims.

Nor exactly a future I get excited about but considering how miserable the present is for a lot of people, you’d be hard-pressed not to call it an improvement.

“As for the French, they haven’t had a proper revolution in too long. They need to stop being so lazy.”

One might perhaps say the ghost of revolution still prowls the Paris streets, down all the restless centuries, wandering incomplete. Nice lyric, but I’ve always wondered if there was much substance behind it. (The ghost of Charlotte Corday probably knows, but the wind took away the words she wanted to say.) What you’ve written is very illuminating.

Another lyric, “Marat, your days are numbered,” is a warning about seeking authority when unsuited for it that I personally take to heart.

Building on the Merlin (and Marat I suppose) examples, there are a couple of original Star Trek episodes that illustrate Science Officer/First Officer Spock making a poor Captain compared to Kirk’s quick-thinking man-of-action approach. One in particular, “The Galileo Seven,” has that as its main point. Of course, with changing times, that distinction was dropped and forgotten in the later movies and sequel series.

I know this post its not about History, so i will refrain from writing too long about the French Revolution, but as a Catalan i can’t resist comenting that you are right on spot about the event afecting the entire 19th Century. Napoleon was unable to conquer Spain, but Liberalism and the Revolutionary ideal were introduced to our country during the short reign of Joseph I, and , together with the epic idiocy of Ferdinand VII, was enough to totally destabilize Spain for the duration of THE WHOLE CENTURY, and i’m not exagerating. Anyone who doubts it will do well to read how many forms of government Spain tried from 1814 to 1931…

And by the way, i would love to know the name of the painting that depicts the taking of the Bastille, and the meeting of the third state.

Well Guillem 48, Napoleon Bonaparte even nowadays is, for most Spaniards,the evilest evil man, a proto-Hitler! Instead entering in Valhalla, spanish painters maybe had painted Bonaparte falling into Hell…However, I think not all in him was bad. He closed the worst excesses of 1789, he was a genious in war and politics, and he expanded classic Liberalism across Europe. Even he abolished the spanish Inquisition…

Hello Mr. Greer, you’ve linked Wagner operas and 1789 French Revolution very brightly! I suppose by the way, you don’t like very much the 1789 revolutionary epic, as good Burkean conservative. Am I fully right? Or maybe I’m wondering too much about your personal ideology. Am I wrong?

Mauve Zone,has a long and vital tradition of harboring working class intellectuals, of which Eric Hoffer might be the best known example. Also, our host in his early years.

Celadon, that’s an intriguing suggestion. The usual interpretation of the failure of the Arthurian dream is that it was driven by the personal inadequacies of those (Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot) most centrally entrusted with its fulfillment, rather than a fatal flaw in the dream itself, which is Wotan’s problem. Still, myths are flexible.

Kfish, I could definitely see a case for that interpretation.

Scotlyn, it’s a good question to wrestle with. The conclusion I reached is that earned power is the power that is freely granted to you by the people who follow you. Gen. George Patton is one good example. The US Third Army would have followed him to Hell and back, because they trusted him and knew he would lead them to victory if anyone could. He’d earned his power. The same is true these days, to turn to a controversial subject, of Donald Trump. Nobody had to support him in this last election campaign, much less pour out the enthusiasm and energy that brought him his victory; his followers feel that he’s earned their respect and support, and that makes his power over them legitimate.

Chris, a lot of people in the managerial class adored the Covid fiasco, since it allowed them to work from home and engage in vast amounts of performative virtue signaling. It was the people in the working classes who had a miserable time of it. As for the debt game, why, look at the history of speculative bubbles sometime. They’re always driven by the same mistakes and end the same way, and the fact that none of this ever stops a new bubble from taking off is to my mind one of the best disproofs of the myth of progress.

Replicant, good! The transition from one intelligentsia to another is always a chaotic time, driven as much by unpredictable vagaries in public taste as anything else. With any luck it’ll be a while before a new intelligentsia succeeds in solidifying, as the longer things stay unsettled in cultural and intellectual planes, the more likely it is that some of the ideas I support might find a foothold somewhere. Still, I’ll stay out here on the fringes dropping ideas into the vortex, and see what happens.

Patricia M, exactly — here in the US we’re all hicks from the sticks, and most of us are proud of it. 😉

Pseudopod, oh, there’s always a market for vaguely kinky Gothic novels. V.C. Andrews managed to tap into that market efficiently.

Joan, that’s an interesting hypothesis, but I’d want to see a little evidence that anything so deliberate was planned and carried out. The claim that culture is manufactured by elites doesn’t actually stand up well to the evidence of history, you know.

Other Owen, it was indeed. In 1500 the Sublime Porte, as the Ottoman government was called in the West, was far and away the richest, most powerful, and most civilized political establishment anybody in Europe had ever encountered. It ruled an empire far larger than all of Europe put together, and made no secret of its plans to conquer Europe — the two sieges of Vienna in the century and a half that followed were both near-run things.

Walt, you could indeed say that, given which album was playing as I was putting the post up! (Jumping songs a bit, I could note that France reached the age of reason, only to find there was no reprieve…)

Guillem, I simply did an image search online for “French revolution” and took the images from there. You might see what you can find.

Chuaquin, like Burke himself, I think the French had very good reason to overturn one of the most effete and incompetent governments in Europe, but I consider it a tragedy that they didn’t simply adopt a constitutional government and settle things that way. Remember that Burke strongly supported the American revolution — as of course do I.

I like Celadon’s observation that our intelligentsia’s old pseudomorphism is pat it’s sell-by date,and that they, titally disconnected from the land, are now going shopping for another one, with a very small menu to choose from. Poor suckers. OF course, it takes more than a few years in any one place t o really develop a connection to the land. I call myself a southwesterner now, after 50 years there, but it took me a long time to do so.

@Chuaquin

I dont know if any Spanish painter depicted Napoleon. Goya did paint about the Independence war and it’s horrors, though.

As for Liberalism, i think that’s the most deadly blow he inflicted to Spain, as it brought a lot of unrest, suffering, and the irreparable loss of many things.

As an example, the confiscation of the goods of the church, that was suposed to be a measure for the good of people created instead a phenomenon wich still exists today in modern Spain, called “Caciquismo”, where some very rich families of the Capital were able to buy enormous pieces of land for ridiculously low prices, including entire villages, that formerly were Church domains.

This created a huge problem, because the new owners were not interested in allowing the peasants to live there. They wanted profit from their new acquired lands, or else to be turned into private hunting grounds.

In addition to that, they “bought” (steal, after evicting the monks) many monasteries that were still working, and procedeed to sack and re-sell their riches, works of art etc.

It was a very bad century for Spain…

JMG, it is interesting that instead of using the intellectual ideal of Liberty the intellectual class in the modern U.S. had to modify it to be ” Democracy” . It seems a poor substitute as an ideal to motivate people in an inauthentic way, but I would guess that Liberty smacked too much of something a Maga dude would have on the flag in the back of his truck.

It was amazing to watch the way the media ( especially the so called high brow media like the NYT) flung around this term as if it was sacrosanct to the democrats. “Trump will destroy our democracy”, was the siren call. While at the same time the democratic elites and intellectuals were busy getting rid of anything resembling democracy anywhere they could find it.

I think the fact that they kept flinging around this tarnished ideal to try and control the masses while it was apparent to all ( except the professors and the editorial board at the Times) that this was the greatest show of hypocrisy modern times contributed to them losing the election.

On the 16th and 17th century decay of women’s social status, but specially in response to @Kfish, #36…

One hypothesis that comes to mind is that women’s work, being more spacely constrained due to the accommodations needed by the pregnant and the nursing, was first on the line to clash with the early industrial revolution, – you know, not the coal powered one, but the earlier one focused on wind and water mills. It is a common trope that Father will keep you fed and Mother will keep you clothed; and the lack of highly mobile engines meant that in those times the labor of lots of strong lads was crucial to keep the supply of the calories needed to keep society running (not to mention, to keep body and soul together). On the other hand, women’s work became increasingly commoditized: surely you could keep spinning and weaving at home… if you were too poor to afford the nice fabrics coming out of the the lord’s mill.

OK John, I understand your view, which isn’t manichean or simplist. Oh, I didn’t remember Burke was friend of American Revolution, thank you for reminding it to me. I’d like to read Burkean books, by the way.

Guillem M. #53:

I share your description of XIXth century in Spain as “bad”, but History never isn’t simple enough to find an only “bad man” as guilty.

I agree it was a pity the sacking of the Catholic Church goods.

However:

Liberalism in Spain was always weaker than its European equivalents; and it was divided in some factions like “Moderate” and “Radicals”. Then, if we want to see the complete picture of spanish disasters in the XIXth century, we must remember as part of that mess, the Borbonic Absolutism and Carlism…Carlist wars were cruel civil wars and they weren’t good and evil game: both sides commited atrocities.

If you didn’t know this news (maybe you knew it, maybe it was unnoticed for you).

In september the city of Dresde received an ambitious funding for a new academy. Its name, of course, is “Richard Wagner Academy”.

https://theviolinchannel.com/city-of-dresden-receives-funding-for-new-richard-wagner-academy/

@Scotlyn #37

“Personally, I struggle with this one, as, over a lifetime, I have become very firmly convinced that no one is BETTER at ruling a person than that person themselves. ”

I’d say that under optimal conditions a person is usually better at ruling themselves than at ruling others, just like under optimal conditions a man is usually larger and stronger than a woman. But conditions are rarely optimal and there are examples of rulers who might not have been good – but their outward performance of ruling others was still far better than their inward performance of ruling themselves and, say, living within a family. (Helmut Kohl comes to my mind, for example).

“how one may properly and legitimately earn the power to rule,”

I concur with what JMG has said. The foundation of “legitimately earned power” is trust. To be justified, this trust has to be earned by deeds and not by words.

Cheers,

Nachtgurke

“I’m far from sure anyone nowadays can even begin to understand just how vast a shadow the French Revolution cast over the century that followed it. Certainly those of us born and raised in America have less than no clue, unless we saturate ourselves in European history and then make a significant effort of the imagination.”

I learnt about this from, of all things, my study of elite historical garb from about the year 1400 onward. The dresses of elite women and formal (court) outfits of elite men were gorgeous things. My interest is on female garb mainly, and the dresses were amazing confections of abundant swathes of truly beautiful fabrics.

Then, the late 1780s and bam! It all goes away. The contrast in style before and after the revolution is hard to overstate. The dresses got downright ugly for a couple decades after, and only slowly ‘recovered’ after around 1820- oddly, right around when you said the intelligentsia started up their tricks again.

You can even see it in the museum collections. There’s a gap there, where lots and lots of lovely gowns got slashed down and resewn into the harsh new style, and nothing new was being made. I almost get a sense of panic from it, like they were desperate to conceal what they had worn before. When you’ve been immersed in centuries of glorious gowns, the suddenness and extremity of the change is startling, and quite stark.

@54

I believe the Dem leadership wanted to lose this election, and adopted a strategy they knew the TDS/”Vote Blue No Matter Who” crowd would embrace but the wider electorate would reject.

I think the timing of the leaked videos of Biden showing symptoms of dementia a few weeks before the Biden-Trump debate followed by the disastrous debate itself was an attempt at politically assassinating Biden.

After delaying their replacement of Biden for a while to increase the damage to his support, they chose a candidate they knew could not possibly salvage the election for Team Blue.

I think they want to have time to rebrand the Dem Party’s stale messaging while leaving most of its policies unchanged (people in the middle were starting to tire of anti-Trumpism & wokeism).

I could be wrong and higher-up Dems could be as out-of-touch as the liberal MSM pundits.

Clay, about demise of small LA colleges, what I wonder is what happens to their libraries? I suppose faculty get first pick, but then what?

JMG might want to buy a campus; I would like a fund to buy up the remains of college libraries and establish a lending library along the lines of the early Netflix.

JMG – Arthur and Merlin, Kirk and Spock, Washington and Franklin… pick your mythic duo! As I filled out some estate planning documents, there was a place to indicate how I wanted to be remembered. I’m too modest to write down “Franklin, not Washington”, too serious to say “Spock, not Kirk” (or “R2D2, not C3PO” in an alternate universe), but maybe “Merlin…”. Quietly competent at the tasks I attempt? That would be fine.

Scotlyn – How does one earn power? I wouldn’t know for sure, since I have very little, but I think that a leader who explained the scope of the possible, then how each faction in society could compromise within their constraints, would qualify. That would include explaining to the greedy that they would rest more easily in their beds if their neighbors did not envy their ill-gotten prosperity. Someone with enough insight into the local ecosystem to help each find work suited to the needs of the community, as well as to themselves, might be given increasing power to make such assignments.

So we’re finally here . All the preliminaries and backgrounds and prosaic prelude opera (Rheingold) have laid the groundwork for one of the pivotal moments in the entire history of art and civilization. The Valkyrie is where Wagner reaches the full measure of his greatness; in the process, as you pointed out, he tore away all the illusions that Europe had had about itself (the effects are not entirely benign; as his disciple-turned-opponent Nietzsche pointed out, we can’t do without illusions. The Birth of Tragedy and all that followed could not have been written without The Valkyrie.)

Among those illusions, as you note, the nature and roots of sexuality. At the very moment where Siegmund is at the depths of despair – the very moment where he has also been fully awakened to his sexual longings by Sieglinde’s beauty and character – he calls on his father. All his childhood trauma resurfaces. It is one of the most thrilling moments that it is possible to experience short of the act of love itself: to sit in a darkened theater and hear a great tenor (you do need a good tenor) with a great orchestra behind him (you also need a good orchestra) illuminate the heart of the human experience with the call on his father to show him the, um sword he’d been promised.. (Wagner would go on in Tristan to explore in yet greater depth the way childhood determines sexuality, but he did it first in the Valkyrie, Freud was really just systematizing Wagner.)