With this post we continue a monthly chapter-by-chapter discussion of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by Eliphas Lévi, the book that launched the modern magical revival. Here and in the months ahead we’re plunging into the white-hot fires of creation where modern magic was born. If you’re just joining us now, I recommend reading the earlier posts in this sequence first; you can find them here. Either way, grab your tarot cards and hang on tight.

With this post we continue a monthly chapter-by-chapter discussion of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by Eliphas Lévi, the book that launched the modern magical revival. Here and in the months ahead we’re plunging into the white-hot fires of creation where modern magic was born. If you’re just joining us now, I recommend reading the earlier posts in this sequence first; you can find them here. Either way, grab your tarot cards and hang on tight.

If you can read French, I strongly encourage you to get a copy of Lévi’s book in the original and follow along with that; it’s readily available for sale in Francophone countries, and can also be downloaded for free from Archive.org. If not, the English translation by me and Mark Mikituk is recommended; A.E. Waite’s translation, unhelpfully retitled Transcendental Magic, is second-rate at best—riddled with errors and burdened with Waite’s seething intellectual jealousy of Lévi—though you can use it after a fashion if it’s what you can get. Also recommended is a tarot deck using the French pattern: the Knapp-Hall deck, the Wirth deck (available in several versions), or any of the Marseilles decks are suitable.

Reading:

“Chapter Seventeen: The Writing of the Stars” (Greer & Mikituk, pp. 341-354).

Commentary:

Few aspects of Lévi’s writing show the immense gap between his time and the present than the idiosyncratic treatment he gives astrology in this chapter. In 1855 astrology was very nearly a dead science. In Britain and the United States it was still a living tradition, but it occupied a space far out on the fringes of society, pursued by a handful of oddball intellectuals interested in occultism and by thriving but isolated pockets in folk culture. In most other European countries it had been driven even further onto the margins of society, landing in the same purgatory of the imagination as geomancy, sacred geometry, and the Lullian art of combinations.

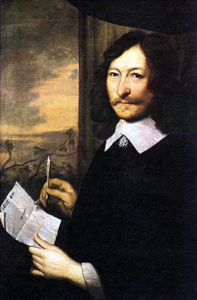

The difference in the reception of astrology between the English-speaking countries and the rest of the industrial world was caused almost entirely by one person, a man who lived some three centuries before Eliphas Lévi took up his pen. His name was William Lilly and he was an English astrologer and writer who lived in the seventeenth century. His most important work was a textbook of the science of the stars first published in 1647, and titled Christian Astrology—the adjective was there to reassure potential readers that the book wasn’t about devil-worship, which may tell you what kind of prejudices he faced. (It may also tell you just how little things have changed since his time.)

Unlike every serious work of astrological instruction before Lilly’s time, Christian Astrology wasn’t written in Latin. It was written in good readable English. Since ordinary men and women who didn’t know Latin could read and use it, it promptly became a bestseller, and inspired other astrologers in England to bring out books of their own in English. As a result, when the scientific revolution arrived on the scene and astrology stopped being popular among the privileged classes, there were plenty of people in less fashion-conscious corners of society who still knew how to cast horoscopes for paying customers, and kept at it. Their efforts alone kept the tradition going until it was picked up by the occult revival Lévi set in motion. That didn’t happen in other parts of Europe

In this chapter we see what would have been left of astrology if Lilly had done the usual thing and written his textbook in Latin. Lévi knew about the planets and the signs of the zodiac as symbols, but he apparently had no idea how horoscopes were cast and interpreted, nor even the slightest clue about the rest of traditional astrology. In our text, he sets out a typical nineteenth-century assortment of substitutes for astrology. In the corresponding chapter of the Doctrine, he described a set of simple predictive tools using planetary cycles: what happened four, eight, twelve, nineteen, and thirty years ago gives you some insight into what will happen now. I encourage my readers to try this out and see how well it works for them; my experience has been, well, underwhelming.

In the present chapter, he adds to this two more practices. The first is the ancient and highly traditional practice of using the phases and the days of the moon as a guide to timing. Most people these days know about planting by the moon, and half of this is a matter of knowing its phases and how they appear to affect plant growth and other matters. This half Lévi has encountered, and summarizes briefly but accurately. The second half of planting by the moon, which uses the elemental characters of the twelve zodiacal signs as a guide to action, our text does not mention and Lévi had apparently never encountered.

What he discusses instead is a far more ancient system, one that survived in European almanacs well into the moderm era but can be traced much further back. This is the tradition that assigns a specific fortune to each day of the lunar month. There’s a version of this in Hesiod’s Works and Days, one of the oldest surviving works of ancient Greek poetry; there are versions of it in very old Hindu writings; there are substantial traces of it in the only surviving ancient Celtic calendar, the bronze Coligny calendar, and in other archaic calendars from around the world. It may be one of the few surviving traces of the oldest of all systems of astrology, the purely solar and lunar system practiced before the five visible planets were identified as being something other than stars sometime before 5000 BC.

Here’s how it works. You begin the cycle when you see the first faint sliver of the Moon setting just after the setting sun—remember, this dates from before anybody thought of writing out a calendar, so the notional date of the new moon doesn’t matter. The night and day following that first sighting of the Moon is the first day of the moon, and each of the days that follows has its corresponding number. There are 28 or 29 days before the moon is no longer visible; then you wait until the first glimpse of the new moon begins the cycle again.

Lévi’s version of the days of the Moon is different from others purely because it assigns the days to the Tarot trumps and the seven traditional planets. The references he gives to Biblical events is straight out of medieval lunaries—that’s what you call a book of the moon’s days, signs, and phases. The “Book of Moons” mentioned in the lively old Elizabethan folk song “Tom o’ Bedlam’s Song” is a lunary:

“From the hag and the hungry goblin

That into rags would rend ye

The spirits that stands by the naked man

In the Book of Moons defend ye…”

I have no idea what kind of market there might be for an old-fashioned lunary these days, but Lévi apparently decided that it was a tradition worth trying to revive. For whatever reason, though, it doesn’t seem to have caught on.

This is not Lévi’s only contribution to ersatz astrology in our text. His other suggestion, though, is an example of his sense of humor, as what he describes as “a very simple way” of using names to work out some simulacrum of a celestial horoscope is anything but. Take a piece of black card stock, he says, and cut out of it the letters of the name of the person whose fate you want to know, so that each letter makes a gap in the card. Make a paper cone with the card over the wide end, look through the cone in the four directions at night, and count how many stars you can see. Write this down. Then convert the letters of the name to numbers, add them up, make another card with the number written on it and then cut out, repeat the operation, and count the stars you see this time.

Add this number to the number you got the first time, convert the total into Hebrew letters, repeat the whole process, but this time figure out which stars you are seeing in the four directions and look them all up in the book Lévi references, which gives the spirits corresponding to each star. Use this as a basis for predicting the fate of your client. All things considered, casting a natal horoscope—even if you do it by hand—involves considerably less hassle. (Yes, in case you’re wondering, I’ve calculated horoscopes that way; I wouldn’t describe it as “a very simple way” of doing the thing, but it’s not as forbidding as many people these days seem to think.)

These two methods of divination aren’t Lévi’s only contribution to the subject, but they’re the only practical methods he gives in this chapter. He also picks up the classic eighteenth- and nineteenth-century notion that the letters of ancient alphabets were derived from constellations, though he doesn’t really seem to do much practical with that belief. Even in his time, for that matter, philologists already knew that this wasn’t true. Instead, as they showed, the world’s alphabets and syllabaries (syllable-based writing systems) are derived, through the same kind of wear and tear that rocks undergo in a streambed, from older hieroglyphic writing systems.

Behind our current letter A, for example, lies a crude little sketch of the head of an ox—you can still see that if you turn it upside down—which was borrowed from Egyptian hieroglyphics by the Phoenicians to represent a glottal stop, and then borrowed from them by the Greeks and used for the “a” sound, since Greek doesn’t use glottal stops to communicate meaning. The Romans got it from the Greeks, and all the western and central European languages got it from the Romans, or more precisely from the Roman Catholic church, since literacy did the usual thing and dropped out of general use when the last round of European dark ages hit.

All in all, in terms of the specific practices and symbolism included in it, this chapter offers less to the modern student of magic than just about any other chapter of Lévi’s book. That doesn’t make it irrelevant; it simply points to the fact that in this area of occultism, modern students of high magic have far more useful options available to them than Lévi ever dreamed of having.

Astrology is perhaps the most dramatic example. The surviving tradition in Britain and America was picked up out of the gutter and put back on its feet by capable practitioners as the twentieth century dawned—the most important names here are Alan Leo in Britain and Evangeline Adams in America. The twentieth century as a whole was quite literally a golden age for astrological study. While there was no shortage of cheap popularizations and shoddy astrological work all through that century, with occultism as with brewing beer, it’s the froth of the surface that tells you that things are fermenting deeper down.

Of course that ferment ran to extremes in various directions; such things always do. The excesses of the psychological school of astrology in midcentury, which too often abandoned prediction in favor of navel-gazing, were balanced by the equal and opposite excesses of the traditionalist school of astrology at the century’s end, which too often went out of its way to pretend that nothing had been learned about the subject since the fall of Rome. In the wake of all this work, however, today’s astrologers have an astonishingly rich smorgasbord of analytical and interpretive techniques to choose from, and whole branches of astrology that had been completely forgotten in Lévi’s day are being revived and put to use as I write this.

The same thing is true in a smaller way of the divinatory method that Lévi called onomancy—literally “name divination.” These days, that’s been absorbed into the broader practice usually called numerology (the proper technical name is arithmancy, but nobody uses that term any more). Calculations based on personal names and birth dates got taken up by pioneering numerologists around the same time that astrology was hitting its stride, and the tentative fumblings Lévi displays in this chapter have long since given way to a body of precise and generally accepted technique. As with astrology, there’s no shortage of cheap inaccurate popularizations, but then the same thing is true of modern physics.

One of the great challenges in reading any really pioneering work well after the fact is precisely that its earlier readers will have gone beyond that first effort. It’s all rather reminiscent of the famous twelve-year-old who read Shakespeare for the first time and said, “Well, it’s pretty good, but it’s full of clichés!” It takes a certain sense of history to realize that it was Shakespeare who coined the phrases in question and made them clichés; that same sense of history is useful for similar reasons when reading our text.

Notes for Study and Practice:

It’s quite possible to get a great deal out of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by the simple expedient of reading each chapter several times and thinking at length about the ideas and imagery that Lévi presents. For those who want to push things a little further, however, meditation is a classic tool for doing so.

Along with the first half of our text, I introduced the standard method of meditation used in Western occultism: discursive meditation, to give it its proper name, which involves training and directing the thinking mind rather than silencing it (as is the practice in so many other forms of meditation). Readers who are just joining us can find detailed instructions in the earlier posts in this series. For those who have been following along, however, I suggest working with a somewhat more complex method, which Lévi himself mention in passing: the combinatorial method introduced by Catalan mystic Ramon Lull in the Middle Ages, and adapted by Lévi and his successors for use with the tarot.

Take the first card of the deck, Trump 1, Le Bateleur (The Juggler or The Magician). While looking at it, review the three titles assigned to it: Disciplina, Ain Soph, Kether, and look over your earlier meditations on this card to be sure you remember what each of these means. Now you are going to add each title of this card to Trump II, La Papesse (The High Priestess): Chokmah, Domus, Gnosis. Place Trump II next to Trump I and consider them. How does Disciplina, discipline, relate to Chokmah, wisdom? How does Disciplina relate to Domus, house? How does it relate to Gnosis? These three relationships are fodder for one day’s meditation. For a second day, relate Ain Soph to the three titles of La Papesse. For a third day, relate Kether to each of these titles. Note down what you find in your journal.

Next, combine Le Bateleur with Trump III, L’Imperatrice (The Empress), in exactly the same way, setting the cards side by side. Meditate on the relationship of each of the Juggler’s titles to the three titles of the Empress, three meditations in all. Then combine the Juggler and the Emperor in exactly the same way. Then go on to the Juggler and the Pope, giving three days to each, and proceed from there. You’ll still be working through combinations of Le Bateleur when the next Lévi post goes up, but that’s fine; when you finish with Le Bateleur, you’ll be taking La Papesse and combining her with L’Imperatrice, L’Empereur, and so on, and thus moving through all 231 combinations the trumps make with one another.

Don’t worry about where this is going. Unless you’ve already done this kind of practice, the goal won’t make any kind of sense to you. Just do the practice. You’ll find, if you stick with it, that over time the relationships between the cards take on a curious quality I can only call conceptual three-dimensionality: a depth is present that was not there before, a depth of meaning and ideation. It can be very subtle or very loud, or anything in between. Don’t sense it? Don’t worry. Meditate on a combination every day anyway. Do the practice and see where it takes you.

We’ll be going on to Chapter 18, “Potions and Magnetism,” on November 13, 2024. See you then!

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

To the extent that Providence allows between now and when it finishes passing through inhabited areas, may Hurricane Milton lessen in intensity and avoid harming sentient life.

May Mariette/Miow (whose recent surgery was a success) make a full recovery and regain full use of her body; may she heal in body, soul and mind.

May Rebecca’s new job position, the start date of which keeps being rescheduled, indeed be hers, and commence as soon as possible; may it fill her and her family’s needs, and may the situation be pleasant and free of strife.

May Divine help be granted to newlywed Merlin (TemporaryReality’s daughter), that she be guided to beneficial information and good decisions that lead to perfect health. May the lump in her breast resolve rapidly with no issues.

May Leonardo Johann from Bremen in Germany, who was

born prematurely two months early, come home safe and sound.

May all living things who have suffered as a consequence of Hurricane Helene be blessed, comforted, and healed.

May Audrey’s nephew John, who passed away on 10/1 after an extended illness, be given comfort and clarity during his transition.

May Kevin, his sister Cynthia, and their elderly mother Dianne have a positive change in their fortunes which allows them to find affordable housing and a better life.

May Tyler’s partner Monika and newborn baby Isabella both be blessed with good health.

May Erika be blessed with good luck and radiant health.

May The Dilettante Polymath’s eye heal and vision return quickly and permanantly, and may both his retinas stay attached.

May Giulia (Julia) in the Eastern suburbs of Cleveland Ohio be healed of recurring seizures and paralysis of her left side and other neurological problems associated with a cyst on the right side of her brain and with surgery to treat it.

May Corey Benton, whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer.

May Kyle’s friend Amanda, who though in her early thirties is undergoing various difficult treatments for brain cancer, make a full recovery; and may her body and spirit heal with grace.

Lp9’s hometown, East Palestine, Ohio, for the safety and welfare of their people, animals and all living beings in and around East Palestine, and to improve the natural environment there to the benefit of all.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

I thought onomancy was the divinatory parallel to what chaos magicians do with their sigils. Oh wait, that’s onanamancy. Never mind.

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Justin, nah, onanomancy would be using that particular practice to foretell the future. It works, too — the answer is always “You will always be a w@nker’.” The magical practice you’re thinking about, on the other hand, is onanurgy. Oddly enough, it has the same effect…

I guess that’s enough self indulgence for now…

It is nice, with this added historical perspective, to see just how much astrology and other things have come along since he set his own massive contribution to the revival in motion.

I hope everyone here has a good rest of the week.

Though I am not actually reading The Ritual of High Magic I always read and enjoy your commentary and learn something valuable. A few years ago at a used book fair I found a copy of Derek Parker’s book on William Lilly and sent it to you, knowing you liked his introductory book on astrology. You wrote back that one of the many projects on your drawing board was a work of historical fiction featuring Lilly as a prominent character. Am I remembering that correctly? If so, is it still in the pipeline? Your early paragraphs about him in this week’s post jogged my memory. Curious if you have Nicholas Campion’s outstanding two volume History of Western Astrology in your library? As always, deep appreciation for all you do.

Jim W

I suspect that, even if he’d had access to the more technical methods of divination, Levi would not have taken them too seriously, since in his understanding divination was a means of triggering intuition, rather than a technique for calculating texts (so to speak) that anyone who could read, could read in more or less the same way. He’s quite clear that discerning letter-shapes in the stars is an arbitrary and even question-begging procedure. His onomantic astrology is another good example, since it too is, as he says earlier, ultimately like reading shapes in clouds.

The main exception is his discussion of the lunar cycle, which was, as you point out, still a part of living lore at the time he wrote (as it is now). I haven’t done so, but it occurs to me that perhaps one could check to see whether and how well Yeats’ phases of the moon align either with Levi or whatever lunary lore was circulating in Ireland in Yeats’ time.

Hi John Michael,

Most human endeavours are constructed upon the shoulders of the great ones who came beforehand. Probably why attempts to resolve problems and uncover unifying theories never seem work, or get around to being completed. At best knowledge is a work in progress, and that’s a good reminder to tuck our egos away (thinking about the sciences there if you were curious), keep them in a safe place where they’ll do little harm, and then get on with the task at hand.

It’s funny, but over my life I’ve met and conversed with a whole bunch of people from all walks of life. It’s quite a humbling experience to see life as an unbroken chain stretching way off into both the past, and the future. Divination fits in there for sure, somewhere, and the currents, movements and eddies all swirl around and around. Discerning the patterns can reveal much, but then here’s the fine joke of it all: On a very practical note, I have troubles trying to convince people that the sun doesn’t shine at night. You’d think that would be obvious. A mystery! 😉 No doubts you’ve encountered such belief systems?

I very much enjoy your political readings.

Cheers

Chris

With regards to Levi’s Great Arcanum, my suspicion is that it is as simple as knowing that one day, perhaps billions of years from now, we will be as evolved as something we might consider a god. At Levi’s writing, something like that might have been too much to publicly state.

Esteemed Archdruid, on p. 351 of your Levi translation, the “…heiroglyphic book of Thoth…” is mentioned. I don’t recall it being mentioned previously (I certainly could have missed or forgotten it) but I’m wondering what work that specifically refers to. Thanks!

Re: reading works of ppl from long ago and experiencing the sense of dislocation from the effect of subsequent readers developing the work further. I had the best time this past several days at a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the agricultural lectures of Rudolph Steiner at the southeast biodynamic conference. For days, people gathered in person at a farm that is utilizing and experimenting with and fitting to context the content of those lectures. And now we got to get together face to face with good food and camping and listen to each day’s lecture read out and then, as before ‘discussion ensues’. How wonderful! And at night we did a couple of the lectures on karma and also the lecture to the youth and one of the medical lectures. With it being the 100th anniversary, somehow it was easier to transpose 1924 to 2024 and see how many of the tendencies he observed then are more strong in their pigheadedness than ever—about materialist science (it can only understand the corpse!) and about ‘cleanliness’ and about the source of life in the plant and in the soil. Because the folks at the conference all actually farm using these principles, but they are part of a ‘society’ built around the work, they face tension around preventing the work from ossifying (something I know you have commented on here) and also preventing the true insight from being watered down. But reading the full text aloud as it would have been heard, we could realize the space where Steiner had a laugh and be reminded in the Q&A (where we repeatedly as a group in 2024 asked the same questions as his 1924 audience and in the same order!) that he often answered that the experiments must be done. Funny his work is basically centered around balancing forces between ossification and mush, between reaching and rooting, between raying up and drawing down… and the same tensions must be properly navigated in the organizational structures. And same w any of these insightful old timers. In any case the experience of the reenactment of the lecture week was wonderful for placing the ideas in context, including the context of actually people actually physically together to learn! And especially with people experimenting by actually farming with sensitivity (as we must experiment with spiritual/occult practice and gain what the nichiren buddhists would emphasize over everything, ‘actual proof’). Again working on communal in person gatherings myself, see link in my name. The proof is in the pudding!

Meanwhile, also grateful for the unbelievable access to once hard to find esoteric knowledge. On the way to the conference ‘the algorithm’ kicked out recommendation of this interview with all sorts of ancient thinking gathered by Robert Gilbert which references the imago stage of the caterpillar when it is actually liquid and the metal paladium which both came up with odd specificity at the conference. The vast collection of old masters we can access is amazing and sorting through and choosing where to look within it is its own task. One of the reasons I appreciate this site and the magic pointed to by various synchronicities. Thanks!

I have no plans to try Lévi’s “very simple way” of celestial divination, but I’d love to learn the trick of cutting the lines of a letter o (or a, e, D, etc.; not to mention 6, 8, 9, and 0) out of a piece of card stock while leaving the middle part(s) suspended in place. Do occult stationery stores sell a special card stock for the purpose? (I suppose one can use a stencil-style typeface but that seems suitable mainly for casting the fortunes of soldiers.)

Justin, well, it provided me with a laugh, for whatever that’s worth.

Jim, you did indeed, and I still have the book. I haven’t proceeded any further with that sequence of novels yet, but I haven’t abandoned the project. No, I don’t own copies of Campion’s history.

LeGrand, I’ve looked into that aspect of A Vision and haven’t found any parallels of any importance. I think Yeats was quite correct to draw a hard line between his system and the behavior of the heavens.

Chris, funny.

Jon, that’s an aspect of it, but he had something much more immediately useful in mind…

Bryan, that’s one of the labels that Lévi uses for the tarot.

AliceEm, I’m delighted to hear this! Blessings to you and all the attendees at the event, if you will have them; Steiner’s agricultural work is among the most useful aspects of his oeuvre and it’s very good to hear that it’s still going strong.

Walt, granted. I have my doubts that Lévi ever tried it.

Thanks, JMG!

I am going to mark the astral light around me with the letters of each entity Levi mentions for the cube and see how things go. I understand that I am the ternary of each pair. If I can do this effortlessly, then it’s time to try going further.

@AliceEm

Thanks for the link to the Heritage Food Fest. It looks like it’s going to be a grand time. I wish I could make it!

A bit OT, but still in the wheelhouse… this is so cool, I had to share (even though I was planning on going into dark mode for the rest of the week):

It’s a Sun Ra Toy Figurine, celebrating 110 years of Sun Ra, and could be used for magical purposes easily:

https://www.strandedrecords.com/collections/newsletter/products/sun-ra-figurine-collectible-action-figure?mc_cid=1af8e8403b

If I had one, I’d surely burn some incense before it on a regular basis.

Anyway, back to work. Head down, hands busy, never mind the hungry ghosts.

Jon, it’s certainly worth trying.

Justin, ha! Among other things, it would make a fine focus for work with the energies of Saturn…

I learned how to hand calculate astrological charts too, as part of the course I took from the American Federation of Astrologers. For people like us old enough to have learned how to do arithmetic by hand and to use log tables, it’s not difficult in principle (AFA even allowed us to use calculators!), but as we both know it is time consuming because of the number of calculations which need to be carried out, which also means it is prone to errors. After having done it I understand why astrological software is a great thing! And why we need to keep printed copies of the ephemerides and tables of houses available through the decline, so that the hand calculations can be done accurately. Otherwise we’ll be in Lévi’s situation again someday: even though lots of books on astrology are available, without the numbers from which we can erect a chart and knowledge of how to do so, we won’t be able to do astrology.

Hearing about how astrological information was scarce for Levi makes me sad how things can be lost so quickly, it makes me grateful that I live in a time where I have easy access to information that occultists in previous generations would have a difficult time getting their hands on. It makes me feel galvanized to help preserve what we have. Unfortunately, easy access to information also means that it is easy to create garbage information, and the truth of a given piece of information has no bearing on how fast it proliferates. Related principle: Brandolini’s Law.

Great salutations to JMG and all the folks here,

I have long been interested in the occult and astrology, then wandered away from those interests for several decades. In years and now months, have become interested in all things Druid (thank you Archdruid for this!). And along with that came opportunities to do some farming / gardening and a growing interest in herbalism and making medicines from what I can grow. This has been life changing and very rewarding.

My question for you and all good folks here, is to help me understand the difference between astrology (classic? / traditional?) and evolutionary astrology and how this might relate to medical astrology and / or evolutionary herbalism?? And I may be asking the wrong question, but c’est le vie!

In gratitude,

Well, one can always hope that something unexpected will turn up. As I remember, there were a couple of astrological books about the lunar scheme of A Vision, but as I remember they were more attempts to apply Yeats’ phases to astrology than to discover or show prior astrological similarities.

By the way, Levi mentions Jean Belot. Belot’sbook, [ Les Œuures de M. Jean Belot [print] : curé de Milmonts, maistre aux sciences divines & celestes : contenant la Chiromence, physionomie, l’art de memoire de Raymond Lulle, Traicté des diuinations, augures & songes; les Sciences steganographiques, Paulines, Armadelles & Lullistes, l’Art de doctement prescher & haranguer, &c, 1640 and 1647] seems to cover a lot of the ground covered by Levi (grimoires, Lullian art, divination, etc), but from a rather more old-fashioned point of view, without Levi’s late 19th-century French sensibility. See https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/L33862 for a description.

The book is available at https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k96136617.texteImage, but I have been unable so far to get the PDF to download. The typography is quite readable, and as should be the case with a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, it has quite a few interesting illustrations. (Google Books has a different scan, but that one has more than a few problems.)

(The physical book itself can be found for sale in various places at various prices, and amazon,fr has a facsimile https://www.amazon.fr/Milmonts-professeur-Contenant-chiromance-physionomie/dp/2405629534 , for a mere 60,00€ .)

SLClaire, it’s a real risk. I encourage anybody who takes up astrology to learn how to do it by hand using log tables, house tables, and ephemerides — even if you only do it that way once a year, that offers some hope that the methods won’t get lost.

Enjoyer, fortunately, time does a fairly good job of getting rid of the crap. There was a fantastic amount of utter garbage marketed as occultism in the 1970s, and nearly all of it’s vanished at this point. In the same way, it’s cheering to remember that ten or fifteen years from now TikTok will have dropped out of fashion, and nearly all of what’s being splashed around on it will be utterly forgotten.

Hankshaw, I’ve never been sure what the term “evolutionary” means when tacked onto “astrology” or “herbalism,” or for that matter anything but “biology.” I think it’s just a brand name. Maybe one of my readers can enlighten both of us about this!

LeGrand, I recall those books. I forget just now which astrologer friend of Yeats tried to find some correlation between phase and horoscope on 300 charts and found none, but hope springs infernal and all that. Thanks for the heads up about Belot’s book — I’ll see if I can get it.

JMG, if it’s not out of line, I’d like to mention that on Monday night I was raised to the degree of a Master Mason. It was a very intense and emotional experience. 13 months have passed since I attended my first dinner. If I may, I’d like to recommend it to any interested men. Lodges have monthly dinners and you may dine at no charge and ask questions.

>it’s cheering to remember that ten or fifteen years from now TikTok will have dropped out of fashion, and nearly all of what’s being splashed around on it will be utterly forgotten.

Oh gods, I hope so! I was the last generation to be raised without constant internet access and unrestricted internet access. It’s really scary to see how bad parenting and predatory technology is melting the minds of children. My kids are not going to have access to iPads or to phones or any of that.

JMG —

I did manage to download it, finally; don’t know what the issue was, but the process was suddenly seamless. In the process, I discovered that the Prado also has a copy of another edition. The BnF is some 234000 kb; the Prado is some 134000 kb : ouch.

After all that, it wasn’t all that I’d hoped — for example, the angel magic turned out to be an exercise in steganography. Verbose, bloviating prayers, conjurations and sermons (full of sound & of fury) to conceal a message. Which made me entertain the idea that some contemporary academic prose might be the same sort of thing. (Could Hegel have been sending concealed messages to someone? Therein lies a tale.) What fun it could be to assemble a concordance or collocation dictionary, reverse engineer a code book, and then publish a paper showing that much of so-called theoretical writing is actually a corpus of steganographic exercises.

At any rate, more practically, I also stumbled across an item in the Beinecke collection — a ms book attributed to Abner Doubleday. (https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/32466186) It’s not completely irrelevant to this actual topic, so please forgive me for quoting a bit. It’s been digitized, so one can page through it, and download page images.

————————–

Autograph manuscript notes and translations from chiefly Italian sources on the subject of tarot probably compiled by Abner Doubleday, circa 1870-1886, including extensive discussion of tarot in relation to the Cabala

The volume includes material about tarot attributed to Alliette, Jean Belot, Thomas H. Burgoyne, Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, Antoine Court de Gébelin, Éliphas Lévi, R. Palmer-Thomas, Moreau de Dammartin, M. Le C. de M. (Louis-Raphaël-Lucrèce de Fayolle, Comte de Mellet), Ramon Llull (cited as Raymond Lulli), Thomas Moore Johnson, Papus, Guillaume Postel (cited as William Postel), and Louis Claude de Saint-Martin, as well as extracts from the Journal of the Theosophical Society, which later became The Theosophist, and The Platonist

The volume includes astrological charts and a group of 78 hand-drawn and colored copies of Italian tarot cards, including examples made by Farinone Battista in Varallo.

“Thus a Cabalist familiar with mystic hieroglyphs will see things in the stars which would not be discovered by a simple shepherd; but the shepherd, from his viewpoint, will find combinations which would escape the Cabalist.”

Levi’s thought here allows me to hook into some recent reflections about awareness and experience, the preamble to which will be clearer and less lengthy in this format:

1. As you outlined recently, Schopenhauer explains that ideas, emotions, sensations, and thoughts are representations (symbols) that humans cannot help filtering reality through. The ego is also a representation, if defined as being my idea of who I am.

2. Schopenhauer also explains that the only thing we can directly experience is the will. Everything else, including the interpretations of the constellations of stars Levi refers to above, is a representation.

3. Yet the experience of will is still an experience.

4. So both will and representation are different sorts of experience, and that an individual ‘experiences’ is more fundamental in a way than either sort.

5. Therefore, experience is more direct to, well, experience, than will is.

If this follows, and given the difficulty of using words to discuss this:

– The act of awareness is itself an experience; that is, it is impossible to get past experience, even if I am aware I am experiencing (and anyway: ‘past’ to where?).

But classing awareness as a type of experience is somehow meaningless as it is just an abstraction, because I cannot insert something in between the being which is now willing the writing of this comment, and the experience of writing it – it just is. I cannot get past it or around it. I CAN get around a representation by realizing it is just a representation, but I can’t do this with experience.

This would seem to be the border of the territory that is impossible to know.

– Based on recent experiences, it seems that one task that occultists and mystics can do is to see that the representations within them have a life of their own (including and especially the ego) and question of what is ‘me’ and what is not ‘me’ seems to bring about a sense of a difference between those deeply held ideas and something which can observe them. But even if awareness of these differences arises in this way, there is the danger of thinking that the result of this awareness is ‘truth’.

– Which in turn brought within me a realization (intellectual, not yet experiential; if that is possible) of the possibility that these truthful-seeming realizations, derived from awareness, are themselves also representations on some other as yet unknown layer! Basically: are experiences, mystical or otherwise, themselves representations? Or is this a word-game that is just the shuffling of abstractions? If the former, this inverts my logic above completely, but the logic seems necessary to arrive at this thought. And now it is unclear whether will still somehow ‘cuts through’ these layers. Essentially, I can’t seem to know ‘any further’ than this, but I’m maybe more aware of how precisely I cannot know.

To conclude: From Levi’s quote above, it is hard to tell whether he is mischievously pointing out that the Cabalist’s interpretation of the stars is just as ‘worthwhile’ as the shepherd’s, despite the learnedness of the Cabalist, and whether he is pointing out not to take the Cabalist’s representations too seriously as ‘truth’. I had arrived at these thoughts before I read this post, and after reading it now I’m less certain that he was being sly with his comment.

I was aware that the symbols Levi is using aren’t truths in the absolute sense, for the reasons above, but they are useful due to their practical value to humans, and there’s a feedback loop involved where, because mages use these symbols, they get charged, thus making them more useful. But this gives me a better idea of how these aren’t absolute truths.

I hope this makes sense!

@JMG

How do you think astrology works? Do you believe it involves some spiritual rays coming from the stars and planets, or is it something else? Also, what is your opinion on whether the stars compel, incline, or simply indicate the processes that are happening through some synchronicity-like mechanisms?

I think there’s another lesson a lot of people seem to miss from the near complete loss of astrology: who knows how many other things were lost, and left only vague and seemingly meaningless symbolism behind? By this point, had astrology been completely forgotten, I doubt that the planets and signs would see much use in occultism: without astrology, there’s precious little to make of the signs. But there are tons of other symbolic systems which seem to hint at something else deeper; and I wonder just how many remarkable things have been lost entirely…

Bro. Jon, congratulations!

Enjoyer, take a moment to remember what internet stuff was hot ten years ago, and twenty years ago. Where are they now? It’s a good corrective to the tyranny of the present.

LeGrand, I also downloaded it, and had a similar experience. Oh, well! As for Abner Doubleday, fascinating — so the guy who didn’t invent baseball also wasn’t a materialist.

Jbucks, interesting. The question is how far you want to push the regression into substrates. Is it really elephants all the way down? 😉

Ecosophian, I haven’t the least idea how astrology works. As for your second question, I’m quite sure the stars incline, they don’t compel — not least because I’ve explored the process of resisting their inclinations when those are inconvenient.

Taylor, good. Very good. A great deal of occult symbolism falls into that category — we have the symbols, but nobody knows any more what it once meant.

Hi JMG,

Have you ever come across an astrologer who uses a machine learning model to make predictions? Such as plugging the astrological data of some celebrities , and historical events that happened to them into an ML model, like neural networks?

@LeGrand Cinq-Mars (#24) & JMG (#28):

Doubleday was a well-known and highly respected member of the Earlier Theosophical Society in the United States (1875-1886), which he joined in 1888. He was regarded by its members as a knowledgeable occultist. See Michael Gomes, “Abner Doubleday and Theosophy in America, 1876-1884,” now available online at:

https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/sunrise/40-90-1/th-tsgom.htm

Note: I distinguish between the Earlier Theosophical Society in New York, which was not centered on Blavatsky alone, and the Later Theosophical Society was organized by Blavatsky and Olcott in India in 1879, which was very much centered on Blavatsky. They were two very different organizations, with different practices and emphases.

See, briefly, chapter VI in my small book om Emma Hardinge Britten, available gratis at: https://www.academia.edu/7254728/_65_The_Unseen_Worlds_of_Emma_Hardinge_Britten_Some_Chapters_in_the_History_of_Western_Occultism_2001_

The Earlier Theosophical Society contimnued more or less along its original lines until William Quan Judge took charge of it in 1886.

Oops:

“which he joined in 1888” whould read “which he joined in 1878.”

@jbucks, I have NOT read Schopenhauer, so this might be completely off base…

“But classing awareness as a type of experience is somehow meaningless as it is just an abstraction, because I cannot insert something in between the being which is now willing the writing of this comment, and the experience of writing it – it just is. I cannot get past it or around it. I CAN get around a representation by realizing it is just a representation, but I can’t do this with experience.”

I don’t think awareness is just a type of experience; I think it is the first conscious experience. Perhaps you cannot insert something between the being writing the comment and the experience of writing it, because the being and its experience are the duality of awareness (a unity and a trinity).

“Based on recent experiences, it seems that one task that occultists and mystics can do is to see that the representations within them have a life of their own (including and especially the ego) and question of what is ‘me’ and what is not ‘me’ seems to bring about a sense of a difference between those deeply held ideas and something which can observe them.”

This author INTERPRETATION OF GREEK MYTHOLOGY – Mythologie Grecque (greekmyths-interpretation.com) considers the ego a deformation of consciousness — “the deformation of a just will for a separate existence” (a separate existence from the Divine, individuation), which could be interpreted as awareness being our individual Kether.

Anyway, fun meditation fodder. Thank you!

First the disclaimer, I have no higher education in any of the sciences, I have little knowledge of astrology. But, as usual, it doesn’t stop me from having an opinion.

So, here it is, it seems that physicists, cosmologists, astronomers have been looking out into that great hall of mirrors they call the cosmos, and the more they see, the less they know.

That telescope out in space looks way back in time, to photons of light emitted close to the purported birth of the universe and sees galaxies when none should exist, at least according to current theory. They see masses of stars spinning faster than they should and so they figure there must be so-called ‘dark matter’ to account for it, except that despite decades of experimentation and sacks of money expended, no dark matter has ever been found. A couple decades ago, some observations convinced them that the universe is expanding at ever accelerating speed. And so they say there must something called ‘dark energy’ that explains it. They say that dark matter and dark energy account for the vast majority of what’s in this puzzling universe of ours. Can they tell us what either one is? They can’t.

At the other end of the scale, nobody understands the equations that explain the workings of the quantum world. Nobody has ever had sufficient intellectual horsepower to understand that thing that gives us wave-particle duality, nobody really understands entanglement, and we could go on and on. For all the equations that predict to ten decimal places, nobody has got an intuitive feel for what they’re talking about. And nobody can explain it in a way that makes sense. None of it comports with the everyday visible world.

They say that massive bodies bend space. Seriously? They have to explain what it is that’s bending. Can they? I don’t think that can. Has anyone heard it? I haven’t.

And yet they laugh at astrologers. Between gasps and wheezes, they say that astrology has no scientific basis, they claim that their own investigative method is superior, it is rigorous and systematic and logical. Yeah and they’ve consumed far more resources than the results as of late would justify. That’s just the first objection, the second being that despite the torrent of money and effort spent in barking up trees that haven’t coughed up so much as a squirrel, they insist on doing more of it.

Could it be that for all the supposed lack of rigor, astrologers have got the visceral grasp that cosmologists and other ‘respectable’ scientists don’t have? Entanglement? Correct me if I’m wrong, but what has astrology been about if not that, the relation between what happens on the earthly realm and what goes on up above? There’s greatly degreed people that tout mathematical formulations but they appear to have no real understanding.

String theory? Go stuff it. Quantum spin? That too.

“They say that massive bodies bend space. Seriously?”

Yes, seriously. The GPS system has to correct for bending of space caused by the earth.

On a much bigger scale is this,

https://www.universetoday.com/160353/jwst-sees-the-same-supernova-three-times-in-an-epic-gravitational-lens/

Straight lines are no longer straight if they pass close to a large mass. Since there is no ether (a fluid that light passes through in space, not to be confused with a chemical compound) it must be space that is bending because light has no mass even though light does have momentum.

“The momentum of a photon is directly proportional to its frequency and inversely proportional to its wavelength. If the wavelength of a photon is known, its momentum can be calculated using the formula 𝑝 = ℎ 𝜆 . If the frequency of a photon is known, its momentum can be calculated using the formula 𝑝 = ℎ 𝑓 𝑐 .”

Wave-particle duality makes everyone’s head hurt. A standard freshman physics problem is to calculate the wavelength of a moving bowling ball.

Don’t let the whimsy of physicists confuse you. The quarks are up and down, charm and strange, and top and bottom. They have to call it something. And my favorite is the barn, the unit of area for the cross section of an atomic nucleus to absorb a neutron.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barn_(unit)

A few weeks ago the question was asked about the limitations of Science. My answer was related to measurement. If you can’t measure it, like the life force or the presence of a soul, then there is really nothing for Science to work with. Astrology suffers from that problem. If a reading of the planets could predict inflation over the next year there would be no problem getting it accepted. If it could predict next week’s price for Bitcoin or Nvidia stock there would be rival supercomputers spitting out predictions around the clock.

But astrology can’t deliver fine grained results. As Zathrus said so eloquently, “This is wrong tool.”

@ SiliconGuy #34

“A standard freshman physics problem is to calculate the wavelength of a moving bowling ball.”

ie –

“A standard freshman physics problem is to calculate the wavelength of a moving [particle]”.

And so we have wave/particle duality right there.

This is an off-topic humorous note. I now have Trump🤗stigmata.

I overzealously scratched my right ear👂and got it bleeding🩸. The ear was itchy, so I scratched. I never realized how much an ear can bleed — turns out, a whole lot.

I can now join the Trump Stigmata Ear Society.

💨Northwind Grandma💨👂🩸

Dane County, Wisconsin, USA

Hi John Michael,

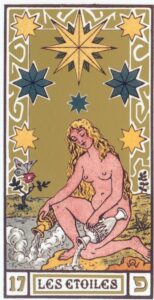

Hmm. Considering the card, it’s notable that the appealing looking young lady is pouring err, life from those two containers into what appears to otherwise be a very parched and barren land. Clearly near to the lady there are some flowers and a butterfly indicating that she herself alone is responsible for the source of life force. And yet, above are stars, and the label of the card translated into English literally means ‘a star or something shaped like a star’, and not the plural form. Also, I couldn’t quite work out why there were eight stars rather than the more expected seven. It occurs to me that there is a distinct possibility, with respect to divination, it could possibly be a two way relationship where the stars affect us, but we in turn ever so slightly impact the stars. Hmm.

From a nature magic perspective, to sit or stand, but otherwise be still in nature, and then open your senses to the goings on all around you, is also a form of divination. A good guide to knowing where to go in a metaphorical sense. Well at least it appears to be from my perspective. The climate is becoming highly variable, so such skills are not to be ignored, and more often I find myself asking the question: Does this action on the land, feel right?

It’s warmer here today, and I was wondering if the seasons are turning for you? There’s been a lot of weather drama in your part of the world lately, and it’s not good.

Cheers

Chris

Siliconguy I figured I’d be hearing from you, not that my post was meant to be a deliberate provocation because it wasn’t.

So, to cut to the chase, you bet, fine-grained as you say, and so you’re right about the fantastical accuracy and breadth and depth of physical theories especially Einstein’s, because no matter what, the thing stands up. Gravitational waves? Say what? And yet, there they are.

So, yes; satellites orbiting the Earth travel in a straight line through curved space, the plummeting object isn’t accelerating as it drops down a gravity well to the surface of a massive body, rather, it is moving at a constant velocity through increasingly compressed space.

But still, my commonsense of the world won’t have it. If space by definition is empty, and yeah, I read about virtual particles, then what is it that’s bending? What is it that’s being compressed? What are we missing?

I get the same feeling when I read about the quantum world. You have a spectacularly successful theory. I’ve read that there’s nothing like it in terms of efficacy. But, it’s like you said, it makes your head hurt. It does not make sense. Spooky action at a distance? How can it possibly be? Obviously it IS, but how?

So, to conclude before our esteemed host loses patience with this increasingly tangential discussion, it does appear to me that this universe has no obligation to make itself comprehensible. And so it also does appear that there are some really, really big holes to fill in terms of understanding what it’s up to. Fine grained yes, no doubt. But are they catching the minnows and missing the whales?

It’s a flaw in my own intellect, which is third rate on a good day, (which is why I went into business in university and not the hard sciences) that makes me think that if something sounds like gobbledegook, it probably is, and never mind that the mathematical formulas are bullet-proof and have stood up to a hundred years of intense scrutiny.

Hi Siliconguy,

Ooo, that’s a bit rough that line of thinking. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but your hypothesis is that because a tool cannot predict: “next week’s price for Bitcoin or Nvidia stock”, then the results can’t be measured, therefore presumably you’re suggesting that it isn’t a science?

Maybe my perspective of the world differs from yours, but humans are a tool using species, and science is simply just another tool in the human toolkit. It works for some things, but for others it’s simply not suited. And it can’t predict next weeks stock prices either. A good example of this methodology in action is that science is very poor at determining whether an outcome produces a quality result. You could equally say the same thing about ‘ethics’, does this scientific hypothesis take into account the ethics of the outcomes – man, they don’t rate a mention.

The natural world we all reside in, is probably way too complicated for a simplistic tool like science to really come to grips with it in any meaningful sense. After all, if it could, why do expert arguments about say pollution or resource depletion not carry any significant weight with the general population – and hey, even scientists take a dump in their own backyards, thus the serious moral and ethical dilemma involved in say, I dunno, making alarming claims about climate change, then jumping on the next commercial aircraft to go to far distant holidays and/or conferences – I heard a scientist a few days ago saying he was about to do just that. You don’t see me doing that act.

To me it looks like a rhetorical trick to demand a tool do something that it clearly can’t do, and then disparage it on that basis. Man, I use intuition all of the time as a guide, and it can’t be measured. Where do such thoughts come from? Who knows, but it’s a useful tool I can tell you. I’d urge you to not be so quick to judge.

Cheers

Chris

Getting rather OT, orbiting the Earth and being swung around on the end of a rope seem to be very different ways of traveling in a circle, but actually they’re not when you think about it.

If I put a belt around your waist and attach a rope to the belt and swing you around, what you experience is the differential pull, your waist being pulled one way, and the rest of you trying to fly away in the opposite direction.

But if I attach gossamer ropes to every atom in your body and swing you around (which mimics gravitational attraction), there is no differential pull. Every part of your body is being pulled at the same rate [Not strictly true. See later]. So you would not be aware of the gravitational force, just like someone in orbit on the ISS.

On the other hand, I could make you lie flat on a large plate, then swing the plate around on the end of a rope. In that case, you would be squashed against the plate by centrifugal force which you would experience as a push in the back, the same as if you were accelerating in a sports car. Which is why they say that being in orbit is a state of continual acceleration.

If the rope was 4,000 miles long, the approximate radius of the Earth, we’re not talking about a big centrifugal force. But if we shorten the rope to mimic increasing gravitational pull, tidal forces become important.

An object in orbit will tend to rotate about its axis because the part nearest Earth will want to orbit slightly faster than the part furthest from Earth. The body will experience this as a differential force trying to pull it apart which causes it to rotate. This is the tidal force. Around the Earth it’s not strong, but in an intense gravitational field such as near a black hole the tidal forces become so large the body gets stretched out and disintegrates. Even atoms will get pulled to pieces.

@Chris at Fernglade,

Re: Eight stars instead of seven: If you look at the stars, all of them are eight-sided, but the big one in the top middle looks like it is two layers… I think it is a duality that is a unity, which makes a trinity. That trinity, plus the seven other stars, adds up to ten.

I think the duality align to the gold and silver jugs of Soul and Spirit (Tiphareth + Yesod = our Kether), with the small dark star above her head being Malkuth. And then the other stars align to the left and right pillars of the Tree.

(And I very much like your idea that we can ever so slightly impact the stars. Maybe we become itty-bitty tiny stars when we complete the Great Work?) (Or maybe we are already itty-bitty tiny stars, but our impact tends to stay in our plane?) Something to go ponder. Thank you!

“A good example of this methodology in action is that science is very poor at determining whether an outcome produces a quality result. You could equally say the same thing about ‘ethics’, does this scientific hypothesis take into account the ethics of the outcomes – man, they don’t rate a mention.”

Quality and ethics are subjective. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Attempts to quantify beauty end up being measures of symmetry and external markers of good health. Ethics depend on the culture. When migration time came the plains Indians left those elderly not strong enough for the journey behind. As my sociology book put it, cultures have the ethics they can afford.

As for Science not being able to predict the stock market, there is a whole branch of stock market math called Technical Analysis. It’s not particularly reliable. But whether it’s wishful thinking or you only have to be close to right most of the time people follow the graphs. (I personally don’t, nor do I chase momentum. I favor the “value investing” model along with the long term compounding effects.)

If astrology works it’s by tilting the table or adding a catalyst to the mix to make certain outcomes more favorable than others. It will not say “advance your ignition timing two degrees for better fuel mileage until the new moon, then return to the original setting.”

In the Good (Expletive Deleted) Grief category of decadent excess,

https://www.hoffmanwest.com/the-wealthy-are-paying-big-money-to-pump-oxygen-into-their-mountain-homes/

Of course a system like that will also filter out the more dangerous radionuclides, and it has to run the house at a slight positive pressure. Hmm. I wonder how big of a fuel tank they installed for the generator?

Re: oxygenating the vacation home. If the power goes out, they’ll just have to relax and wait a few days to acclimate naturally. After a week in Denver at 5000′, I was able to cross-country ski up and down mountain trails at 10,000′, but my wife (who flew out just for the weekend) did not tolerate the altitude well. (This was about 30 years ago, when we were young and clueless.) “Food, drink, and supplemental oxygen; all part of being a gracious host in the Colorado mountains.”

I hope they don’t try to burn candles or oil lamps too close to the oxygen source!

Hi Siliconguy,

We seem to be on the same page here with science – good as tool for some things, useless when applied to others.

Of course you may have noticed a tendency for us humans to occasionally take things too far and try to use a round shaped tool head on a square peg?

Here we must politely disagree. When the market appears to be rigged in that new records are being reached on a semi-regular basis, any idiot can produce a model which suggests that the price of some stock will rise, and then look like a genius. All I can suggest is that if such increasing capital yields, exceed the price of money, then leverage will continue to increase. Eventually all strategies are subject to diminishing returns and there is an end point.

An old ignition light, or nowadays a diagnostic computer, would be used for such work, ignoring the moon cycles. It seems very arbitrary to me to suggest that because a tool cannot do some random test – which you get to decide – that the tool is clearly no good. For the record, I don’t burn a candle for astrology, but there’s no excuse for applying sloppy logic to a discussion.

Divination has long been associated with humans, and it is very applicable to the gentle art of warfare and/or hunting, just for two examples which spring to mind. The risk with having known patterns, is that they’re known, and either enemies or prey, are smart enough to be able to discern and interpret such signs. If you’ve ever pitted your wits against foxes and/or rats, and I have, it can be a humbling experience. Introducing the random element of divination is a strategic advantage, thus the billionaires quote.

How do you decide what actions and paths to take for your future?

Cheers

Chris

@hankshaw 19 re: My question for you and all good folks here, is to help me understand the difference between astrology (classic? / traditional?) and evolutionary astrology and how this might relate to medical astrology and / or evolutionary herbalism??

So, I must say I really like Brian coulter evolutionary astrology channel AND. I really like Sahjah popham (sp?) book evolutionary herbalism. Here’s what I think it means. 1) recognizing that the stars ‘incline’ things to happen, and that we all have certain inclinations, karma, skills and challenges, the point of checking what the stars are inclining to happen has the purpose in evolutionary astrology of identifying the energies of a moment, how they interact with one’s own tendencies, and ‘working with’ those energies to improve one’s balance and equanimity and generous love and happiness in this life, to bring ‘higher octave’ expressions of various astrological energies into one’s approach to being.

2) evolutionary herbalism name is a bit funnier to me. The important part of that *excellent* herbal/alchemical book is work identifying common threads in use of herbal energetics across many traditions (with alchemy being the Western European tradition’s expression of these common tools/messages/tones). He describes a good method for communicating directly w plants and then says ‘look, these varied cultures have common threads because they all talked directly with the local reps of the plant kingdom’. THEN the evolutionary part is that he wants to restore this body/mind/soul capacity to a wounded People Who Have Lost Their Way. It’s more of a return than an evolution in my perception. Tho there’s a truth about ‘returning to where one began and seeing with new eyes.’ Fwiw that phrase is in a series of seven Chinese line drawings, it’s the culmination of the journey and I used it on a business card of mine when I was younger and I can’t find the sequence ever again (so help me if you know where it is please!) and I only always have ‘returning to where one began and seeing with new eyes’. Which is a kind of evolution. A spiral in fact.

Noted only because horoscopes were unjustly maligned.

Kamala: What we see is so hard to see that we lose faith or a vision of those things we cannot see but must know.”

Reply:

Kamala Harris is a fortune cookie stuffed inside a magic eight ball and wrapped inside the horoscope page of your local newspaper.

Due to lack of local newspapers with horoscopes I can’t speak to how they are now, but I remember the advice being vague but clearly stated. “Be alert for financial opportunities” being an example.

@JMG: I wonder! I already seem to have my hands quite full with just a single elephant! Maybe the regressing hall of mirrored elephants is just a trick of this particular hall. 🙂

@RandomActsOfKarma: That’s interesting about your thought that awareness is itself a duality, and the first conscious experience. Hmm… I’ll need to ponder that. Thanks also for the link. That’s a useful way to see the nature of the ego, and it seems to fall in line with what I have been reading about it. And awareness as being our individual Kether makes sense, too, and that reminds me of John Gilbert’s writings on the tree, which I should review in light of this. I always appreciate the food for thought!

Minervaphilos, nope. The astrologers I know all prefer to learn things for themselves, rather than using some technogimmick or other as a crutch.

Robert M, thanks for this! I wish he’d invented baseball; it would be even better, as a way to get skeptics bent out of shape, than pointing out that America’s favorite author of children’s books, L. Frank Baum, was a lifelong occultist.

Smith, for what it’s worth, I understand how space can bend, though I’m not sure I can explain it. That said, you’re certainly right that astrology looks downright prosaic compared to the N-dimensional handwaving that’s being used to prop up the failed models of modern physics these days.

Northwind, all I can say is you might want to be careful around golf courses. 😉

Chris, well, John Gilbert used to say that the reason there are eight stars is that this card corresponds to the 8th sphere of the Tree of Life, but that was only true in his eccentric version of the Cabala. (Admittedly, it works, and it’s the version I use these days, but still.) As for weather, it’s a beautiful autumn day in Rhode Island right now, 51°F and sunny; the bad weather basically ignored us.

Siliconguy, maybe it’ll seep into their apparently oxygen-deprived brains and cause them to notice what’s right in front of their faces for a change. As for Kamala, um, most fortune cookies, magic 8-balls, and newspaper horoscopes make much more sense than she does.

Jbucks, “The regressing hall of mirrored elephants” should have been a painting by a neglected Surrealist artist named Ludo Malkovich. That, or the one hit song, #8 on the charts in 1972, by the otherwise forgotten acid-rock band Electric Gecko…