With this post we conclude a monthly chapter-by-chapter discussion of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by Eliphas Lévi, the book that launched the modern magical revival. Here and in the 43 months before this we’ve plunged into the white-hot fires of creation where modern magic was born. If you’re just joining us now, I recommend reading the earlier posts in this sequence first; you can find them here. Either way, grab your tarot cards and hang on tight.

With this post we conclude a monthly chapter-by-chapter discussion of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by Eliphas Lévi, the book that launched the modern magical revival. Here and in the 43 months before this we’ve plunged into the white-hot fires of creation where modern magic was born. If you’re just joining us now, I recommend reading the earlier posts in this sequence first; you can find them here. Either way, grab your tarot cards and hang on tight.

If you can read French, I strongly encourage you to get a copy of Lévi’s book in the original and follow along with that; it’s readily available for sale in Francophone countries, and can also be downloaded for free from Archive.org. If not, the English translation by me and Mark Mikituk is recommended; A.E. Waite’s translation, unhelpfully retitled Transcendental Magic, is second-rate at best—riddled with errors and burdened with Waite’s seething intellectual jealousy of Lévi—though you can use it after a fashion if it’s what you can get. Also recommended is a tarot deck using the French pattern: the Knapp-Hall deck, the Wirth deck (available in several versions), or any of the Marseilles decks are suitable.

Reading:

“Chapter Twenty-two: The Book of Hermes” (Greer & Mikituk, pp. 387-418).

Commentary:

We have reached the end of Lévi’s magnum opus, the book that redefined magic for the modern world and set the occult revival of our time on its way. It was standard in Lévi’s day, at least, for authors to refrain from introducing anything really new in the last chapter of a book, and our text follows that old and by no means outworn tradition. This chapter, lengthy as it is, is simply a summary of some of the essential points of the book, and serves as a virtual podium for one more tub-thumping oration of the kind that Lévi’s nineteenth-century readers expected and he himself was more than willing to provide.

Thus it is possible to sum up Lévi’s points, and his achievement, with a good deal less prolixity than he himself used. The essential themes of this chapter, and of the doctrine and ritual of high magic as Lévi understood them, are three in number.

The first is the existence of a secret language of number, letter, and symbol, embodied in the 22 trumps of the tarot deck, with which the great narratives of classical and Biblical mythology can be reinterpreted in terms more meaningful to modern minds than the literal interpretation imposed on them by the scholars and priests of Lévi’s time. The second is the existence of the astral light, the subtle substrate of life and consciousness, which can be directed by the human will and is responsible for the apparent miracles performed by the prophets, sages, and wizards of legend. The third is the Great Arcanum: the secret knowledge that brings mastery over the astral light and transforms the seeker into the adept, at once prophet, priest, and king, equipped with powers that represent the closest human approach to omnipotence.

This is what Lévi has been talking about all through the last forty-three chapters. This is the vision of individual and collective human possibility that fired his imagination, and transformed the minor literary figure and political rabblerouser Alphonse Louis Constant into the prophet of a new age of magic. The book we’ve read is the magical talisman he used in his attempt to make that vision a reality, with at least some measure of success. As we review this chapter, then, it’s appropriate to survey his three themes, and assess the successes and failures of the vision itself and its consequences in the 170 years since Lévi wrote.

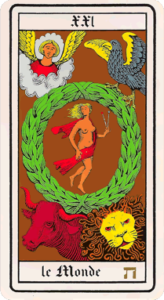

The tarot deck in Lévi’s time was just beginning the ascent to its modern role as the most widely used divinatory oracle in the Western world. In his day, to most people who had heard of it at all, it was an obscure card game played in various corners of Europe. Antoine Court de Gébelin started the tarot on its way to the big time by proclaiming it a relic of ancient Egyptian wisdom, and Jean-Baptiste Aliette, under his pen name Etteila, had introduced it to the French public as a divination deck. Lévi took these ideas, added a connection to the Cabalistic Tree of Life, and redefined the tarot not only as a universal key to the world’s mystery traditions, but also as one of the most important survivals of ancient magic, the secret oracle handed down from the priests and wizards of the legendary past.

It’s probably worth being frank here: in historical terms, he was wrong. The tarot was invented sometime between 1415 and 1425 by Marziano da Tortona, secretary to the Duke of Milan, as a clever game. (This has been documented for more than a century in European publications; it says little for the level of scholarship in occult circles in the English-speaking world that so few are aware of it here.) Taken up by the noble classes in a dozen northern Italian towns, it passed through various forms and variations before the specific deck used in Milan became the basis of the version nearly everyone uses today. Passed from Italy to the French town of Marseille, the tarot became the most popular card game among the sailors and dockworkers of that bustling port city. From there it spread to various corners of Europe, including Paris, where it came to the notice of Court de Gébelin and Aliette.

Does that mean that the tarot can’t be used for the purposes Lévi had in mind? Not at all. To begin with, as a product of the collective imagination of the late Renaissance, the tarot embodies the worldview of that era, which is for all practical purposes identical with the worldview of the modern occultist. Furthermore, once occultists took up the tarot, they went to work on it, changing the imagery and in some cases reordering the cards to fit the role that Lévi gave them. Whether the old tarot decks had any particular esoteric content, in other words, classic occult tarots such as the Oswald Wirth deck, the Knapp-Hall deck, or Pamela Colman Smith’s Rider-Waite deck are dripping with it. They are well suited to the kind of work that Lévi assigned to the deck, as generations of occultists have learned.

Very few of the writers and practitioners who followed Lévi’s lead, however, used the tarot for the core purpose he had in mind: the reinterpretation of the symbolic narratives of classical and Christian mythology as a new gospel of human freedom. I’m not at all sure why that project so rarely caught fire among students of Lévi’s work. Attempts were made, some of them highly elaborate, but few people were interested. Nor did many follow the hints Lévi dropped so liberally and connect the tarot with the ars combinatoria, the art of conceptual algebra launched by Catalan mystic Ramon Lull in the Middle Ages, which was practiced so enthusiastically by the mages and occult scholars of the Renaissance.

Instead Aliette, with his exclusive focus on divination, had the last laugh. Divination, for most people, became the be-all and end-all of the tarot, and retains that status today. It interests me to see that even among students of the old occult schools that preserve Lévi’s vision of the tarot, such as Paul Foster Case’s Builders of the Adytum, the magnetic pull of divination is a force to reckon with. It may be that the temptation to know the future in advance is just too strong; it may be that our culture tried so hard to slam shut the doors of perception that a backlash in the direction of prophecy couldn’t be avoided. Still, at least for me, reading what Lévi had to say about the tarot is a poignant glimpse of a road that could have been taken, and wasn’t.

Lévi’s advocacy for the concept of the astral light, on the other hand, was destined to have a much greater success. Partly he had the momentum of the age behind him. From the late eighteenth century onward to the present, the life force was constantly being discovered by European and American scientists. No matter how savage the suppression of the idea and its discoverers became—and it was often pretty brutal—the life force just kept revealing itself to unprejudiced researchers.

One consequence of this history is the plethora of names assigned to the life force. Franz Anton Mesmer called it animal magnetism, Carl von Reichenbach called it Od, Wilhelm Reich called it orgone, T. Galen Hieronymus called it eloptic energy, and the list goes on. Occult practitioners generally called it the astral light when they didn’t borrow the concept of ether from nineteenth-century science, or make use of Asian names for it such as prana and qi. Despite the fulminations of dogmatic materialists, this force of many names is recognized and understood throughout alternative culture today, as often as not veiled under the vague but useful metaphor of “energy.” To the spread of the concept of the life force, and its enthusiastic and productive application all through the alternative scene nowadays, Lévi made a significant contribution.

And the vision of adeptship through the mastery of the Great Arcanum? That had a longer and stranger road ahead of it. For a century after Lévi’s time, that vision remained firmly in place, not least because most occult schools all through that period claimed a connection with actual, living adepts of the kind Lévi wrote about. The Theosophical Society had its Mahatmas, the Golden Dawn had its Secret Chiefs, and so on; it was very rare for anybody to try to start an occult school without staking some kind of claim to sanction from such beings, no matter how thin or obviously fraudulent that claim might be.

Two things happened, however, as the years unfolded. The first was that the concept of adeptship got inflated to an absurd degree by devout but overenthusiastic believers, and turned into a way of avoiding the challenges Lévi hoped to encourage his readers to embrace. H.P. Blavatsky, the effective head of the Theosophical Society for most of its first twenty years, tried her best to insist that her Mahatmas were incarnate human beings living in southern Asia, whose unusual powers were simply the product of many lifetimes of spiritual practice; ordinary Theosophists blithely ignored her and reimagined them as world-ruling demigods unimaginably far above the mere human level. The same thing happened over and over again, as people tacitly rejected adeptship as something they could hope to attain and pushed it off on imaginary supermen of planes far higher than ours.

That led to the second thing I had in mind, which is that these supposed supermen failed to live up to the reputations foisted upon them. The classic example is the Krishnamurti affair of 1929, in which Jiddu Krishnamurti formally refused the role of World Teacher his Theosophical mentors expected him to act out, and dissolved the organization founded to glorify him; the result was a widespread crisis of faith from which the Theosophical Society has never really recovered. On the other end of the spectrum connecting high drama with low farce were the would-be Masters who turned out to have feet, or other bodily appendages, of clay. Quite a respectable number of self-proclaimed superhuman adepts turned out to have the same cravings and weaknesses as the rest of us—and then there were the ones who claimed to be immortal, and proceeded to refute their own propaganda by dropping dead.

By the end of the twentieth century, as a result of such antics, the only responses most esoteric teachers could expect for such claims were raucous laughter and a shortage of students. Less absurd forms of self-promotion accordingly became more popular. This is by and large a good thing. Somewhere in the rise and fall of fantasies of Secret Chiefs, however, Lévi’s far less extreme vision of adeptship got lost—and it may yet be worth recovering.

The crucial point here is that the Great Arcanum does in fact exist. In its simplest form, a form that can be practiced by the beginner, it can be pieced together without too much difficulty from Lévi’s own repeated allusions and hints. In terms of the Tetragrammaton, the fourfold name of the Divine that structures so much of his teaching, the י or Yod of the Great Arcanum is the will, trained, purified, and focused to a single point. The ה or Heh is the imagination, equipped for the task by the systematic study of a symbolic alphabet such as the tarot. The ו or Vau is the breath, used in a variety of ways, including those relatively simple methods of which Lévi gives quite adequate descriptions. The ה or Heh final, lastly, is the use of any of a number of specific material substances as a focal point for the astral light.

None of this is especially obscure. All of it is covered in the book we’ve just finished reviewing, and in fact our author gives a number of specific examples of the entire working of the Great Arcanum in action, though of course he is careful not to flag them as such. A few careful readings of this book, therefore, and a little delving into the literature of medieval and Renaissance magic that influenced Lévi, will be more than enough to reveal the method as well as the forms of training needed to master it.

Any reader of this book, in other words, can become an adept of the kind Lévi imagined, given a willingness to invest the necessary time, intelligence, and hard work in that process. The possibilities of his or her adeptship, in turn, will be measured precisely by how much of those inescapable ingredients each aspirant is willing to put into the work. Thus the doors of the sanctuary stand open to all those willing to enter. Will you be one of them? That, dear reader, you alone can decide.

Notes for Study and Practice:

It’s quite possible to get a great deal out of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by the simple expedient of reading each chapter several times and thinking at length about the ideas and imagery that Lévi presents. For those who want to push things a little further, however, meditation is a classic tool for doing so.

Along with the first half of our text, I introduced the standard method of meditation used in Western occultism: discursive meditation, to give it its proper name, which involves training and directing the thinking mind rather than silencing it (as is the practice in so many other forms of meditation). Readers who are just joining us can find detailed instructions in the earlier posts in this series. For those who have been following along, however, I suggest working with a somewhat more complex method, which Lévi himself mention in passing: the combinatorial method introduced by Catalan mystic Ramon Lull in the Middle Ages, and adapted by Lévi and his successors for use with the tarot.

Take the first card of the deck, Trump 1, Le Bateleur (The Juggler or The Magician). While looking at it, review the three titles assigned to it: Disciplina, Ain Soph, Kether, and look over your earlier meditations on this card to be sure you remember what each of these means. Now you are going to add each title of this card to Trump II, La Papesse (The High Priestess): Chokmah, Domus, Gnosis. Place Trump II next to Trump I and consider them. How does Disciplina, discipline, relate to Chokmah, wisdom? How does Disciplina relate to Domus, house? How does it relate to Gnosis? These three relationships are fodder for one day’s meditation. For a second day, relate Ain Soph to the three titles of La Papesse. For a third day, relate Kether to each of these titles. Note down what you find in your journal.

Next, combine Le Bateleur with Trump III, L’Imperatrice (The Empress), in exactly the same way, setting the cards side by side. Meditate on the relationship of each of the Juggler’s titles to the three titles of the Empress, three meditations in all. Then combine the Juggler and the Emperor in exactly the same way. Then go on to the Juggler and the Pope, giving three days to each, and proceed from there. You’ll still be working through combinations of Le Bateleur when the next Lévi post goes up, but that’s fine; when you finish with Le Bateleur, you’ll be taking La Papesse and combining her with L’Imperatrice, L’Empereur, and so on, and thus moving through all 231 combinations the trumps make with one another.

Don’t worry about where this is going. Unless you’ve already done this kind of practice, the goal won’t make any kind of sense to you. Just do the practice. You’ll find, if you stick with it, that over time the relationships between the cards take on a curious quality I can only call conceptual three-dimensionality: a depth is present that was not there before, a depth of meaning and ideation. It can be very subtle or very loud, or anything in between. Don’t sense it? Don’t worry. Meditate on a combination every day anyway. Do the practice and see where it takes you.

This concludes our study of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic. I want to thank all my readers for their attention and enthusiasm during the period of almost four years we’ve put into this project! Next month we’ll begin a new sequence of book club posts; stay tuned.

One curious example of someone who discovered the life force is Rupert Sheldrake.

In Morphic Resonance, Rupert Sheldrake distinguishes his “organicist” view from both the materialist and “vitalist” views — the latter being described as belief in a life force. When I read this, I thought this was strange, since his notion of morphic fields seems more akin to fleshing out what the life force is like than denying its existence, asserting that it has more structure to it than gravity or electromagnetism.

(William James made a similar comment about Bishop Berkeley’s philosophy of subjective idealism: Berkeley thought he was denying the existence of matter, but James pointed out that his ideas merely propose a different account of what matter is.)

Of course, Sheldrake surely felt the need to play scientific politics, and it’s probably benefited him. Despite his fringe status, I suspect he has a lot more supporters (both open and closeted) within the natural sciences than he would have had otherwise.

I’ve been quiet on the Levi book club posts for a while now, being caught up in other things, but I have been following along with them and reading the chapters in the book. Thank you very much for this series! I learned a lot from the book and your posts!

Slithy, I’ve been a fan of Sheldrake’s work since not long after A New Science of Life first came out. It’s not quite true to say that he’s simply a vitalist — rather, he’s rediscovered (or come up with a new name for) a different aspect of the occult worldview. His “morphic fields” are precisely equivalent to Dion Fortune’s “tracks in space.” Mind you, his theory is completely compatible with vitalism, it’s just that he’s exploring a different facet of the inner planes.

Jbucks, you’re welcome and thank you! I’ve just had the whole series accepted for publication in book form, so The Great Arcanum: A Commentary on Eliphas Lévi’s The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic will be in a more enduring form in a year or so.

@JMG(#3):

I’m really looking forward to this new book of yours!

JMG,

“His ‘morphic fields’ are precisely equivalent to Dion Fortune’s ‘tracks in space.'”

But since he’s focused on the tracks which physical matter most readily respond to, wouldn’t it be fair to say that those corresponding to living beings are laid down in the life force — the structure in the life force that I mentioned? And if animism is true, as pretty much all other cultures believe, is there really a difference in kind between the tracks for organic beings and the tracks for inorganic matter?

In other words, it seems to me what Sheldrake’s discovered is the etheric plane.

If there’s a difference I’m missing here, I’m happy to be corrected!

So Zelazny’s Amber series is doing the combinatorial method. Huh.

When will your book, compiled of your posts on Levi for the last four years, be out?

Thank you for being such a capable tour guide. Thanks also for your and Mikituk’s translation. It’s been a blast reading the book and your commentary while working the GSF material.

I think the vision of Adeptship is alive in some places still. I wonder if the other vision he had for the Tarot can be given another kickstart. Frankly, I like to study the tarot, but have learned that I prefer other forms of divination: I Ching, the Sacred Geometry Oracle, and Lenoramand have been less panic inducing in me than the tarot. Of course I have a lot less anxiety than I did in the time I was using tarot.

Part of the adepthood aspect of things, I think got scrambled too in the obsession of Crowleyites and those influenced by that end of things in the quest for the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel. It seemed that alone was all they equated with adepthood for so long, that other aspects of occult and magical development got ignored. Other teachers have since emphasized a gradual realization of this, rather than always focusing on the intense rituals.

Is Yeat’s A Vision, still going to be the next book for the book club? It has my vote anyway.

Firstly, thank you for this book club. Among other things, reading it in French as you suggested greatly increased my fluency (at first painfully slow) and has made other interesting studies available as a result. So this experience has been quite fruitful for me in many ways.

“ Very few of the writers and practitioners who followed Lévi’s lead, however, used the tarot for the core purpose he had in mind: the reinterpretation of the symbolic narratives of classical and Christian mythology as a new gospel of human freedom. I’m not at all sure why that project so rarely caught fire among students of Lévi’s work. ”

As a graduate of catholic school, I found this aspect of Levi quite interesting. Wirth and another French book “meditations on the tarot” continue the theme, and do it well to my reading.

In my opinion however, the reason these efforts died out was largely due to a deep permutation of that tarot interpretation with the older hierarchical catholic worldview (a universal church and Holy Roman Empire). I’m thinking that was the reason the tarot were quickly modified and adapted when brought to England (where catholic influences were suspect) – and then declined more generally along with that worldview and the church itself over the course of the 20th century.

Hello JMG and the commentariat. I hope you are well. I am currently re-reading Stars Reach and it is a fantastic book I can’t wait until my children are old enough to enjoy it.

JMG,

Thank you so much for guiding us through Levi’s book these past four years. You (and Sara) have had a huge impact on my life. For example, I have a genetic disposition to high blood pressure which I have been able to address by adopting a more-or-less vegetarian diet that started with Levi’s forty day fast. And I have become a serious student of Jewish mysticism which you referenced in one of your posts. Now that we’ve completed the course, I think I am finally ready to meditate on the combinations beyond the twenty two paths in the Kabbalah.

Cheers!

Robert M, thank you!

Slithy, I’m not at all sure that Sheldrake has discovered the etheric plane as such. Some of his experiments — for example, the one with the Japanese nursery rhyme — focus on astral plane phenomena. Thus, at least in the works of his that I’ve read, he’s succeeded in demonstrating that there are nonphysical realities that have a property corresponding to inertia, and that the effects of this property can be observed in life (in occult terms, the etheric plane) and thought (in occult terms, the astral plane). It’s an achievement of great importance precisely because he’s focused on a general property of the planes rather than one specific plane.

Bruce, Zelazny had a very solid background in occult thought. The experience of going through the Golden Dawn’s Neophyte grade is echoed in Corwin’s experience of walking the Pattern that I’m pretty sure Zelazny was a GD initiate.

AA, in the spring of 2026.

Justin, Crowley’s major problem — or one of his major problems — is that he never really got out from under the fundamentalist Christianity he grew up with. Thus his scheme of aeons was an echo of Christian Dispensationalist theology; in the same way, the Holy Guardian Angel was his surrogate Jesus, who was supposed to show up and save him. That’s not especially helpful as an approach to occult training, nor is the kind of intensive wallowing in emotion-packed ritual the only or the best way to achieve the state of adeptship. I think it’s high time for calmer and more certain methods to take the lead again. As for A Vision, yes — but we’ll talk more about that next month.

Paul, that’s quite a plausible explanation, I think. It’s still unfortunate.

Nelson954, delighted to year that you’re enjoying Trey’s adventure! (I’ve deleted the business about AI, since that’s entirely off topic.)

Claus, you’re most welcome and thank you.

Second sentence of the post is: “Here and in the months ahead we’re plunging into the white-hot fires of creation where modern magic was born. “, which uses the present continuous tense. Since this is the last post on the topic, perhaps a past tense would be more consistent?

Well said about Crowley. I never thought of the HGA as his surrogate Jesus, but that makes a ton of sense giving all the ways he backlashed his upbringing. The pendulum swings…

Thanks also to the commentariat for great discussions and much food for that as always. Off to go fishing again.

OT but I have a new essay up, and I like to think it embraces the notion that “The opposite of one bad idea is usually another.” For those who don’t care much for the narrow definition of family on offer by the far rightward end of things, or the complete abolition of family by the far leftward end of things, I offer my thoughts on “Stew Pot Families in a Stew Pot Nation.” Stew pots are a better metaphor than the homogenized goop of blended families, and a stew pot nation is one that encompasses a multitude of stew pots, as we move back to the extended family forms in the post-plutonian-post-nuclear family age.

https://www.sothismedias.com/home/stew-pot-families-in-a-stew-pot-nation

The book that launched the modern magical revival which has this goal – “the secret knowledge that brings mastery over the astral light and transforms the seeker into the adept, at once prophet, priest, and king, equipped with powers that represent the closest human approach to omnipotence.” I guess Aleister Crowley doesn’t fall into that category completely, Jack Parsons? Dion Fortune? Gareth Knight? Levi himself? Or does the true adept stay more hidden and anonymous? They walk among us unrecognized at large? Or you aware of anyone who became the type of adept described above as part of the modern magical revival?

Mr. Greer, do you review the comments before they are posted? I have a sensitive question. And also some of the questions I have may be off topic to this chapter 😓.

Is there like a forum for the previous chapters? Like the riddle in chapter 21, others in the comments said that the absolute value of aleph maybe 1. I believe I understand why and a table in the Sefer Yetzirah says one as well. My thinking lead me to a different answer.🥺

I apologize for being annoying, you’ve probably already answered these sorts of questions.

Thanks

Hi John Michael,

Always a good day when the vocabulary is enhanced. The word, ‘prolixity’ was entirely new to me, and at this point in the discussion I feel the need to veer off into an only barely related, but also rather amusing narrative digression. So, the story begins, way back when, maybe twenty years ago, although it could have equally been twenty one years now. The mind forgets these small details, and one often wonders in the small dark hours of the night: Where have these details gone? Philosophers have long debated these sorts of issues and come to no great conclusion at all, when in fact the simplest answer is that the detail fell behind the couch, or were stuck between cushions. Who’s to argue with such logic, and candidly nobody seems to have conducted the search. Anyway, so there… 😉

Yup, prolixity… A fine word. Thanks!

The book alone is a powerful act of will.

What a mystery and path you’ve proposed. Hmm. Do people genuinely want the freedom to exercise their will consciously?

Cheers

Chris

Re: ‘Life force’ relation to ‘astral light’

It kind of threw me that your summary feels like it’s pretty directly equating life force w astral light (tho you don’t *exactly* say that, more by association and proximity, ie “Occult practitioners generally called it the astral light when they didn’t borrow the concept of ether from nineteenth-century science, or make use of Asian names for it such as prana and qi.”). I have understood astral light acting on astral plane more as a thought-image-metaphor-correspondence-trackinspace force, while the qi or life force is more literally the vital spark which animates something to aliveness. Then riffing on sheldrake you said, “Thus, at least in the works of his that I’ve read, he’s succeeded in demonstrating that there are nonphysical realities that have a property corresponding to inertia, and that the effects of this property can be observed in life (in occult terms, the etheric plane) and thought (in occult terms, the astral plane).” Further emphasizing this distinction which I thought I had properly grasped. Am I imagining an inconsistency where there isn’t one?

JMG,

Thank you so much for leading this book study. I didn’t think any book could compare to the Cosmic Doctrine’s mind-blowing-ness, but the Doctrine and Ritual does. I very much appreciate your patience in explaining things.

Commentariat,

Thank you so much for all the wonderful discussions.

At this link is the full list of all of the requests for prayer that have recently appeared at ecosophia.net and ecosophia.dreamwidth.org, as well as in the comments of the prayer list posts. Please feel free to add any or all of the requests to your own prayers.

If I missed anybody, or if you would like to add a prayer request for yourself or anyone who has given you consent (or for whom a relevant person holds power of consent) to the list, please feel free to leave a comment below and/or in the comments at the current prayer list post.

* * *

This week I would like to bring special attention to the following prayer requests.

May Jennifer’s newborn daughter Eleanor be blessed with optimal growth and development, and may her tongue tie revision surgery on Wednesday March 12th be smooth and successful and followed by a full recovery.

May Mike Greco, who has a court case coming up on the 14th of March, enjoy a prompt, just, and equitable settlement of the case.

May Cliff’s friend Jessica, who is suffering from severe postpartum depression, be blessed and soothed; may each day take her closer to an outlook of joyful participation in the world.

May Other Dave’s father Michael Orwig, who passed away on 2/24, make his transition to his soul’s next destination with comfort and grace; may his wife Allyn and the rest of his family be blessed and supported in this difficult time.

May Viktoria have a safe and healthy pregnancy, and may the baby be born safe, healthy and blessed. May Marko have the strength, wisdom and balance to face the challenges set before him. (picture, update)

May Cliff’s friend Jessica, who is suffering from severe postpartum depression, be blessed and soothed; may each day take her closer to an outlook of joyful participation in the world.

May Peter Evans in California, whose colon cancer has been responding well to treatment, be completely healed with ease, and make a rapid and total recovery.

May Debra Roberts, who has just been diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer, be blessed and healed to the extent that providence allows. Healing work is also welcome.

May Jack H’s father John, whose aortic dissection is considered inoperable and likely fatal by his current doctors, be healed, and make a physical recovery to the full extent that providence allows, and be able to enjoy more time together with his loved ones.

May Goats and Roses’ son A, who had a serious concussion weeks ago and is still suffering from the effects, regain normal healthy brain function, and rebuild his physical strength back to normal, and regain his zest for life. And may Goats and Roses be granted strength and effectiveness in finding solutions to the medical and caregiving matters that need to be addressed, and the grief and strain of the situation.

May Kevin’s sister Cynthia be cured of the hallucinations and delusions that have afflicted her, and freed from emotional distress. May she be safely healed of the physical condition that has provoked her emotions; and may she be healed of the spiritual condition that brings her to be so unsettled by it. May she come to feel calm and secure in her physical body, regardless of its level of health.

May Linda from the Quest Bookshop of the Theosophical Society, who has developed a turbo cancer, be blessed and have a speedy and full recovery from cancer.

May Frank R. Hartman, who lost his house in the Altadena fire, and all who have been affected by the larger conflagration be blessed and healed.

May Corey Benton, who is currently in hospital and whose throat tumor has grown around an artery and won’t be treated surgically, be healed of throat cancer. Healing work is also welcome. [Note: Healing Hands should be fine, but if offering energy work which could potentially conflict with another, please first leave a note in comments or write to randomactsofkarmasc to double check that it’s safe]

May Open Space’s friend’s mother

Judith be blessed and healed for a complete recovery from cancer.

May Peter Van Erp’s friend Kate Bowden’s husband Russ Hobson and his family be enveloped with love as he follows his path forward with the glioblastoma (brain cancer) which has afflicted him.

May Scotlyn’s friend Fiona, who has been in hospital since early October with what is a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, be blessed and healed, and encouraged in ways that help her to maintain a positive mental and spiritual outlook.

May Jennifer and Josiah, their daughter Joanna, and their unborn daughter be protected from all harmful and malicious influences, and may any connection to malign entities or hostile thought forms or projections be broken and their influence banished.

* * *

Guidelines for how long prayer requests stay on the list, how to word requests, how to be added to the weekly email list, how to improve the chances of your prayer being answered, and several other common questions and issues, are to be found at the Ecosophia Prayer List FAQ.

If there are any among you who might wish to join me in a bit of astrological timing, I pray each week for the health of all those with health problems on the list on the astrological hour of the Sun on Sundays, bearing in mind the Sun’s rulerships of heart, brain, and vital energies. If this appeals to you, I invite you to join me.

On adeptship and the Great Arcanum:

The important of limits is a critical part of your philosophy, both ecologically and esoterically. What do you think are the hard limits of what a human being can achieve with magic?

Some would argue that there is no upper limit to what can be done with magic, others argue that nothing can be done at all. I am certain you choose the middle road.

Thank you much for this enlightening series JMG and congratulations on the forthcoming book! Very exciting news.

A much needed encouragement on my end was contained in this week’s post regarding Lévi’s hope for the reinterpretation of the Tarot as a new gospel of human freedom. Albeit not western nor Christian, I have been laboring to work out a system with the Tarot in order to present (and create an interest in) the genius of Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras. The Sútras were once titled “The Certainty of Freedom” by a very wise scholar and I believe that to be a truth I am attempting to share in my workings.

Much gratitude to you!

Yogaandthetarot Jill C

Thank you for being such a capable tour guide. – Justin #8

Amen to that. Have to be careful with what is said and how it’s said so the student doesn’t go way off course.

When I was a kid in Sunday school they taught us the Hail Mary prayer. I didn’t know what ‘hail’ meant.

‘Blessed is the fruit of thy womb Jesus’; I didn’t know what a ‘womb’ was and so I figured it was something for growing fruit that’s blessed. How did the fruit become blessed? I figured they used holy water to water the fruit. The thing is what did it have to do with Jesus?

‘Holy Mary mother of God, pray for us sinners’ is pretty straight forward and even I couldn’t mess that up, being a most heinous sinner myself according to the parish priest who told me at confession that I ought to be ashamed. I came out of the confessional shaking, convinced I was going to Hell.

And so for a long time I thought that there were two women named Mary, one that was ‘hail’ and one that was ‘holy’, the latter of which was the mother of God.

So God has a mother? Then that must be Jesus’ granny if Jesus is the son of God. To put it mildly I was immensely confused. And they never told us what a ‘virgin’ is.

And Mrs A, the upright and stern, never once smiling Mrs A, who was our Sunday school teacher and who was apparently put on this Earth to drink vinegar, did not welcome questions, especially from impudent snots like us.

Viking, duly corrected.

Justin, thank you for this.

BeardTree, the serious adepts are generally unknown to the public. I’ve been privileged to know a few.

Charlotte, I moderate all comments and delete anything off topic. No, there’s no forum for previous chapters — it’s as much as I can do to keep this blog running!

Chris, most people don’t want anything to do with that freedom. Some choose otherwise. Those latter are the ones that Lévi wrote for.

AliceEm, as I noted back a ways, Lévi wrote before the planes were differentiated. I’ve tried to bring that differentiation to bear on his teachings.

Random, you’re most welcome!

Quin, thanks for this as always.

Enjoyer, there are many hard limits to magic — enough of them that it’s difficult to enumerate them. Perhaps the easiest way to summarize them is to say that you can only do with magic things that nature does by herself — at most, you can arrange for those things to happen at times that are convenient for you.

Jill, you’re welcome and thank you. Best wishes for your project!

Smith, and the sad thing is that so many people thing that mindless repetition of stock prayers can accomplish anything at all…

On p.394 it states: “By adding each of the columns of the squares, you invariably obtain the number which is characteristic of the planet”.

For Saturn, the table on p392 has 3 columns each adding to 15. (I can’t see how to get from there to 8 or did P have a different number for Saturn?)

For Jupiter … 4 columns each adding to 34. (ditto for 3)

But for Mars (9?) on p393 it has 5 columns adding to 65, 65, 56, 62, 65 (is there an error here?)

Likewise for Sun (1?): 111, 101, 111, 111, 111, 84 (another error maybe?)

A thought, not being Catholic, but sufficiently interested in ritual that works, I wonder if the Tridentine Mass achieved the Great Arcanum, for its recipient. It would make a lot of sense, something being called down, passed around, then given back up, and during that moment of balance in the polarity working, something else comes through and is concentrated into the Host.

It’s a funny this this Arcanum, the closer you get to thinking you’ve cracked it, the more words fail, and perhaps the more you don’t actually have it at all 😉

Thank you again for the last 42 months. My mind remains blown by the Cos Doc, and this has just added to it. Can’t wait for the next book.

Ah, I apologize, I wasn’t clear enough.

When I spoke on the hard limits of magic, I wasn’t speaking of the limits of the effects of magic on the external, physical world. I understand those limits. I was asking about the upper limits of the internal, self-transformative potential of magic. That part is more unclear to me, although perhaps the answer is the same.

And so it finally comes to an end. What a ride it has been! Thank you so much, Archdruid, for this enlightening experience.

I have been thinking about mathematics recently. So we stare at a bunch of equations and diagrams, visualise something in our minds, and we need to put in some effort to focus our minds to do this visualising. This does seem a lot like the components of the Great Arcanum – the equations and diagrams are the symbols which direct our minds to visualize (in other words, use the imagination), via these visualizations we direct our willpower to tackle the problem we are trying to solve with mathematical tools. Am I overthinking this?

I adore the eternal chicken-or-egg paradox you left dangling so enticingly in your closing “The possibilities of his or her adeptship, in turn, will be measured precisely by how much of those inescapable ingredients each aspirant is willing to put into the work. Thus the doors of the sanctuary stand open to all those willing to enter.”

Since “the will, trained, purified, and focused to a single point” is one of those inescapable ingredients of adeptship, one’s success will ultimately be measured by one’s willingness (i.e. the unity of one’s will) to then masterfully train one’s will towards unity. Unity with what; from what exactly has one’s will been divided? What magical potency in the greater will have we managed to divide ourselves off from, by attempting to stake a feeble claim on some tiny piece we like to call ‘mine’? How delightfully, confoundingly simple, yet frustratingly, convloutedly elusive at the same time!

We are always each of us standing at a threshold that is precisely as open and as closed as we are willing it to be. We are always each of us expressions of divine will, utilizing that will to act out myriad dramas of unwillingness. When we are willing to enter, the doors to the sanctuary stand open. When we are willing to stay separate instead, the doors to the sanctuary quite naturally stand closed.

Whichever doorways to divinity we have defiantly closed, whichever thresholds we happen to find ourselves facing, that is precisely where we belong, learning whatever willingness or unwillingness may be needed to open or close the doors we’ve imagined separating us. The unity of will that we are not yet willing to put into the work, is always the gift of the threshold we’re currently struggling to cross. When viewed from its other side, its doors naturally stand wide open — so much effort expended in rediscovering how little effort was needed in the first place! We must amuse the gods to no end.

The fascination with divination to the exclusion of other worthwhile endeavors is an interesting phenomenon. I recently began enjoying a web serial called ‘A bright and shiny life’, which at first glance is a garden variety sword-and-sorcery story about a child soldier becoming an adult. It was only after I read a ways into it that I realized – despite divination being one of the most commonly practiced occult sciences in real life, very few fantasy authors include it in their settings. It’s nice to read a fictional account of a character who makes use of divination in a military context without it rendering him invincible.

I wonder whether folks imagine they always know the right question to ask, which makes them overestimate the usefulness of divination. Has anyone done daily divination practice with a one-two effort of asking what question to ask as one’s first divination, then divining the answer in the second? It seems like a slightly more interesting variation on the ‘what kind of day will I have?’ practice, but the obviousness of it makes me think it might not be widely done for a reason.

KN, we copied the squares out of the French edition as given; Lévi probably got them from an old printing of Agrippa. The numbers for Saturn in the old cosmology are 3. 15, and 45. The others? Errors, with which printed copies of the squares are riddled.

Peter, you can be sure that Lévi had that in mind.

Enjoyer, nobody knows. It’s entirely possible that we couldn’t understand the answer if we did know it.

Rajarshi, no, this is the kind of exploration Lévi wanted his readers to do.

Christophe, excellent! Yes, by all accounts the gods find us endlessly amusing.

Chris, that’s a good point about fantasy fiction. The debasement of fantasy magic into firepower is very widespread. As for your double question, the challenge would be interpreting the first reading. How exactly would a tarot deck, say, suggest that you need to ask about your maternal uncle’s health insurance?

@Chris H. #30 re: “Asking about asking” for Divination

Something that I’ve experimented with a bit is using “finger-testing,” a method of kinesiological divination I learned from the Modern Order of Essenes material shared by our host, to “vet” whether or not to ask a particular question of another oracle (like the Ogham or Runes), and to fine-tune the question. The method is that you make a loop with the thumb and index finger of each hand, with the loops interlocking, then think of the question and try to pull the apart. If both rings hold, the answer is “yes,” and if either breaks, the answer is “no.” In my own experience, it’s fairly reliable for sussing out how my subconscious might feel about things and what my body wants/needs (“should I eat X for this meal?” or “should I do Y workout this morning?”), but not so great at prediction or “bigger,” more complicated questions, though as I said, it seems to do alright at guiding me as to how to ask and interpret such questions of another oracle.

So, for example, I had a question this week about a course of action I was thinking about taking. I used finger-testing to ask yes/no questions about whether I should ask, what kind of time frame I should specify, and so forth, then when I had “what should I most know about [doing the thing] in the coming week?” I asked the Runes that question, got a very clear “don’t do it” answer, then used finger testing to explore a bit why not and how to understand what the Runes were trying to tell me.

Not sure if it would work for anyone else, but so far, it seems to be helpful to me, so that’s an option you might explore.

Cheers,

Jeff

” and the sad thing is that so many people thing that mindless repetition of stock prayers can accomplish anything at all…”

So, perhaps doing a discursive meditation session on the meaning of a prayer or mantra before reciting it a few hundred or so times might be a good idea?

It always stuck with me that in Learning Ritual Magic, you and the other authors stated that the Will exercise was the only exercise one needed. If I named it wrong, I’m referring to the exercise where you pay attention to your body while being conscious of your breath. It strikes me now that this is a form of the Great Arcanum now that I see you lay it so plainly.

Hey JMG

It was fun while it lasted, though you could kick the can down the road by discussing the supplementary material added after chapter 22, such as the “Nuctemeron”.

Apart from that, I am curious about this passage about the connection between the magic squares of the planets and the Tarot.

“By adding each of the columns of these squares, you invariably obtain the number which is characteristic of the planet, and, by finding the explication of that number through the hieroglyphs of the Tarot, you look for the meaning of all the figures, either triangular, square, or cruciform, that you shall find formed by the numbers. The consequence of this operation will result in a complete and profound understanding of all the allegories and of all the mysteries hidden by the ancients under the symbol of each planet, or rather of each personification of the influences, either celestial or human, that govern all of life’s events.”

I am a bit confused about what Levi is describing here, I get that he is suggesting that you can add up the numbers of a magic square and then find the tarot card corresponding to the answer for the purposes of understanding the planet of the square, but what is he talking about in regards to the “figures, either triangular, square or cruciform”?

Isaac, put it down to my exposure to Japanese esoteric Buddhism, maybe, but to my mind if you’re going to use a mantra, you need at the very least to know who it invokes and what your intention is in reciting it. Properly speaking — again, in Japanese esoteric Buddhism; I can’t speak to other traditions — the mantra isn’t used alone; there’s always a mudra, or position of the hands and body; there’s always a mandala, a symbolic visual focus for the gaze; there’s always a visualization — usually, you’re visualizing yourself as the being you are invoking — and there’s always a solidly formulated intention. Yes, discursive meditation would help; you can also get all this from a competent teacher.

Luke, good. Yes, exactly — all the other exercises are helps for those who can’t do that one right. (Very few of us can.)

J.L.Mc12, he’s being evasive as usual. There’s more than one number generated by the magic square; for example, the Saturn square has 9 squares, each row and column add up to 15, and the sum of all the squares is 45. 9 is the Hermit, 15 is the Devil, and 45 is the Empress (45 – 21 = 24, and 24 – 21 = 3). Lay out the cards in various patterns — say, three rows of 7, with the Fool left out, or 4 rows of 5, with the Fool and the World left out — and see what geometrical figures are formed by the positions of these three cards, as though by drawing lines connecting them with each other. Notice what cards are surrounded by them and what cards are outside. Meditate on all of it.

Hi John Michael,

Agreed, it’s hard work and sometimes deeply unpopular, even if it is the wiser path. Oh well.

Hey, just had a brain flatulence insight episode category two, and I’d be curious as to your thoughts. 😉 Anywhoo… It is precisely because many of the current crop of leaders in the west (not all, I shall say no more on the hot button topic…) aren’t exercising their will, plus refuting divination, that their responses are so easily predicted and neutered. The outcome is baked into the cake.

Even the very long dead Sun Tzu in his treatise ‘The Art of War’ recommended divination, for good reason. When caught in a tight spot, I make a habit of introducing random actions and elements.

Cheers

Chris

In the tradition I’ve learned mantra sadhana in, which is Hindu, some of that is used (not always mudras, or a mandala, but you’d use a picture or visualization of the deity to focus on after invoking the deity, and there’s other things like nyasas beforehand and so on), but simple mantras as remedies can be practiced without everything, though at least knowing the deity and the meaning of the mantra is important. Some mantras though, especially the longer ones like Savitur Gayatri and Maha Mrityunjaya have such powerful, subtle and complex meanings, and I was just struck with the idea of meditating on the meanings before practicing, because the meaning usually isn’t the primary focus, and sometimes when doing japa for a while, the meaning of the mantra is forgotten.

Riffing off Rajarshi’s comment on mathematics being a way to The Great Arcanum and my own observation I mentioned before that mathematics done with a calculator feels different, it’s striking to me that doing mathematics with a calculator is stripped away not just of much of the deeper meaning, but also of the imaginal component. It does not take nearly the same kind of imagination to press buttons on a calculator as it does to solve an equation. The willpower is still there, after a fashion, but without the imaginal component, it is not remotely the same.

More generally, it strikes me that in a lot of cases, working with a computer strips away at the very least the imaginal component, and in some cases the physical as well; one example that springs to mind is the difference between a natal chart hand crafted on paper compared to the ghostly image of one on a computer screen; or the difference between a budget in a spreadsheet and a budget in a paper book. What all of this implies is that in a good many cases, the digital way of doing things will not allow for The Great Arcanum, while analog methods will accidentally stumble toward it. They will not get all the way there, but in many cases they can probably get quite close.

Plenty of theories have been given for why so much of pop culture, political systems, and other aspects of society seem to have gotten stuck on an endless repeat of the worst aspects of the late 1980s and early 1990s, almost as if much of the world has lost the ability to have new ideas, but these speculations would seem to imply a metaphysical reason: the digital age prevents people from reaching toward the start of the Great Arcanum merely by living, and so stripped societies that adopted it of much of the vital energy that used to exist merely because engineers worked with mathematics, architects built models, astrologers cast charts, artists drew and painted, actors performed, musicians played, accountants dutifully maintained books, and so on.

I found a copy of The Gnostic Gospels at the bookstore. I absolutely must keep this away from my mother. She would blow an artery, or carry on until I did.

I do wonder what would have happened if the Gnostics had won. It would make an interesting alternate history.

Mary Magdalene, Thomas, and Mathew got special teachings, but Peter did not? And he carried the grudge to the end of his days? I did a bit of cross checking and see there is quite a modern effort to make Peter less of a misogynistic butthead than tradition would have it.

I may burn for this, 😉

“And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church,”

Calling someone a rock is also an insult to their intelligence. Was Jesus a bit peeved at Peter? Or was Matthew annoyed with the man? It’s Matthew’s gospel after all.

If the Gnostics had won out women might have gotten a better deal from the church.

In a more secular vein, I ran across this relentlessly cheerful piano piece should you need cheering up.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=rsSRpyxNJPc&pp=ygUHZ2FtYXpkYQ%3D%3D

I’ve been lightly following from afar, if that makes sense. Thank you for this group of posts and the Cos Doc before it. Was quite timely this week with ‘The World’ – a wise woman once pulled that card in a reading for me in 1994 and I never forgot it as it was so weird. This week it made it make sense. The Tarot is up there with the I Ching and certainly more colourful.

I’d just like to be a little esoteric here and remind that ‘Will’ can magically affect you from Higher Powers as well, with agreements that span lifetimes. Once you’re on this path you can wander a bit and take breaks but it seems that’s it. I’ve been looking at spiritual alchemy recently and with my name meaning, ‘Healer’ it suddenly dawned on me that anyone who does this right is in the healing business, whether this is healing below or the ‘Great Healing’ above. (Of course when I say ‘healing’ I’m looking at the etymology – ‘To Make Whole’ – that’s always behind worthwhile work to be done).

Jay Pine to any Argonauts that are listening

Hi John Michael,

Sorry, this is way off topic but things are moving so fast. In breaking news… Trump administration asked to explain after Australian universities told to justify US-funded research grants

I’d wondered about this topic for a very long while, and now we know.

Between you and I, what I’m hearing in the near to middling distance is a clarion call to get back to productive work. In some ways it saddens me that anyone could have thought that things could be otherwise. The Sirens sang a tuneful deceitful melody of luxuriating whilst others laboured long and hard in adverse conditions. I’d heard the song and knew it for wrongfulness. But what do you do?

Cheers

Chris

Thank you JMG, for this amazing ride through Levi’s book. It has had a profound effect on my change in consciousness. I went back to look for the first post, which was in May of 2021. How the world has changed since then.

Coincidentally, I’ve had several 22 synchronicities this week. When I noticed that this was chapter 22, it made me even more gobsmacked.

And thanks to all the others who participated in the comments. You’ve really helped me get through the book.

Thanks JMG for guiding us through this book. Without your help, I don’t think I would have even finished reading the book let alone understand anything of it. I will be looking forward to getting the book of your commentary next year.

While there are multiple reasons, I think one overlooked reason for the shift to Harry Potter magic in fantasy is because fantasy now has to provide the kind of “gee whiz” stories that were once the province of science-fiction: the trend in science-fiction for the past couple of decades has been to so-called “hard sf,” which allows authors to display their science chops and readers to suppose themselves sophisticated for appreciating it.

In its own way, this may be an indicator that it’s slowly sinking in that technological progress has hard limits, but it’s left a hunger for the kind of marvel that SF once provided (and which myths and legends provided earlier civilizations). Since the pretension to sophistication has hit fantasy as hard as science-fiction, and since most readers don’t know the first thing about real-world magic, the mantra “it’s magic, just go with it” still has power where “it’s science” doesn’t.

Hi John,

Last chapter already… huh? Thank you for the ride; couldn’t have done it without you!

JMG,

I also want to mention to mention that all the other exercises (besides the LRM Will exercise) are a lot of fun (and also powerful). That alone makes them worth doing. Which is part of the reason they are necessary for a lot of us. Regarding the Will exercise, most of Gurdjieff’s system is centered around a form of the Will exercise, called “Self Remembering”. I think there was something else I was going to say, but completely forgot, chalk it up to Friday beers. So I’ll simply say, thank you for this book club, it was great. Looking forward to the Yeats edition.

“What all of this implies is that in a good many cases, the digital way of doing things will not allow for The Great Arcanum, while analog methods will accidentally stumble toward it.”

Digital calculations have a discretization error. Every quantity must be represented as a power of two. The bits are on or off. See also TTL logic. You can get arbitrarily close to the Truth, but you can’t actually achieve it unless Truth happens to be a power of two or an integer. Then you have the register size to contend with. Remember single precision and double precision math from the days of the 80387 or 68882 math coprocessors? It’s good enough to throw a spacecraft at Pluto and miss it by the desired amount, but it’s not “exact”.

It’s the same as pi in decimal or the square root of three. Remember your algebra teacher making you carry the radical through the equation? The square root of three is exact. 1.732 is not.

Chris, cerebral flatulence or otherwise, that’s precisely correct. Since our current “leaders” have never had to develop any personal character at all — being born to rich parents and then getting very good at pleasing your superiors doesn’t give you that — they have no capacity to will worth noting, and since they don’t see the point in divination they can’t even inject some randomness into their decisionmaking process. Thus they’re as repetitive and predictable as a cheap sitcom.

Isaac, it’s a good idea! The more reflection you put into a spiritual practice, the deeper the effect will go.

Anonymoose, that’s an intriguing suggestion, and a plausible one.

Siliconguy, it would have been a very different world — to my mind, a better one, but your mileage may vary.

Jay, of course, but I don’t want to pile on the weirdness too fast!

Chris, let me get this straight. The US government was funding research at Australian universities, and now that the Trump administration is asking the recipients to justify their expenditures, the Australian government is throwing a hissy fit? I’m sure Trump would be happy to let your government pay for the research instead…

Jon and Kay, you’re welcome and thank you.

Slithy, hmm! Yeah, I could see that.

Inna, you’re welcome and thank you.

Luke, to Yeats! (clink)

I haven’t commented much on these posts, nor been able to pursue the associated meditations, but I’ve followed along from the start and have found it a fascinating and helpful supplement to the other occult/magical work I’m doing, so thanks very much!

Looking forward to A Vision, of which I was able to find a copy of the edition edited by Jeffares that you recommended for only a modest premium with some patience and frequent searches of multiple book-seller websites.

Cheers,

Jeff

Thank you to JMG for this Doctrine and Ritual series. Your essays each month were essential in making clear many of the concepts and examples in the book. Thanks also for everyone that commented. Even if my input was sporadic, I enjoyed the conversations.

“the serious adepts are generally unknown to the public”

From your experience you think that having a public personality (for instance, as an occult author) hampers becoming a serious adept? I don’t know you well enough to know how serious of an adept you are, but I imagine you’re at least a semi-serious one. 😉 The people I know personally who I would consider serious adepts don’t court fame, but don’t hide their lamp either. I sometimes feel the tension between these as a podcast host and author, but also to me, becoming an actually serious adept seems much more important.

Greetings all

JMG said: “BeardTree, the serious adepts are generally unknown to the public. I’ve been privileged to know a few.”

What can you partake with us about adepts while keeping their identities confidential, as it must I imagine.

Thanks and Regards

Hi John Michael,

Yeah, true. We have spoken in the past about this subject and I do wonder if the ability to perceive a vision, in whatever form, is linked to will? Presumably ‘will’ is part of the doing process for enacting a vision which results in action?

Re-reading the article I couldn’t quite grasp if it was the university sector which was upset, or the government. The lady in the photo really reminded me of those socialist posters you see plastered on walls every year in trendy inner urban suburbs.

It’s not unreasonable to ask what the funds are being spent on, and who are they being granted to.

It seems really weird to me that all these smart people genuinely appear to believe that sinking the US dollar or creating inflationary stresses through sheer debt excess was a good idea. Somehow they can divorce their actions from the consequences, and that’s quite a remarkable feat. I’m just left scratching my head about this story, it’s not like it is complicated.

Cheers

Chris

Jeff, glad to hear it.

Scotty, you’re welcome and thank you.

Isaac, I’m not an adept. In the jargon of the old occultism, I’m an initiate, which means I’m at least potentially on the way to adeptship but not there yet. Yes, being a public personality is a significant burden to the practitioner; it can be a necessary task, and in my case is required for karmic reasons, but it’s always a distraction.

Karim, the ones I’ve known seem very ordinary at first glance. They dress in whatever clothing is customary where they live, and do nothing to draw attention to themselves At most, you might notice a quality of calm good humor even in difficult situations, and a tendency to precise, unhurried action. They don’t advertise themselves in any way, quite the opposite, and they — not you — decide when it’s time to let you know a little of what they’re up to. Nor are they looking for students; if they decide you need to learn something they’re as like as not to point you to some public or semi-public organization where you can learn it. Their own work is solitary and specific to themselves, and they don’t discuss it.

Chris, oh, granted. One of the most astonishing things about the current leaders of the corporate-bureaucratic state is their utter inability to think beyond the present moment and notice what kind of future their own actions are creating.

Hey JMG

It just so happens that awhile ago I did some tarot meditations that had a similar geometric basis, but had nothing to do with the planetary magic squares. Instead I think I derived it from the tree of life, but I don’t remember the details on the top of my head.

Would this meditation Levi described still work well with the Rider-Waite deck, or must it only be done with the marseille?

Hi John Michael,

That’s a pretty common issue right across society, and probably one of the most important questions that only a few people out on the fringes are even asking: What kind of world are we leaving for the future?

In many ways it gladdens me to see a controlled demolition going on. I was of the opinion that a wild unpredictable downwards lurch would have been much worse if history is any guide.

For the life of me, I fail to comprehend why the leadership down here (which faces a poll in less than two months) is getting behind the European adventure. It’s of no strategic interest to Australia, none at all. At least the opposition party are pointing this out now. As an investment we’re talking all costs and no benefits in that endeavour when there are local issues to consider. And the same numpties are putting a bloke in front of your President who has publicly slammed him, and somehow they’re lamenting the poor outcomes from negotiations. We talk about a lack of vision, but all that’s either stupid at best, or incompetent behaviour at worst. I don’t really know what to make of all this. None of this story is complicated, it’s just like the future question posed above, everyone’s pretending it’s not there, when it is.

Cheers and baffled!

Chris

@ Chris at fernglade re: random elements, ‘When caught in a tight spot, I make a habit of introducing random actions and elements.’ — that’s why I only Love backgammon of the intense two person games; thanks to the Turks for game with strategy AND dice 🙂

@jill #22 and JMG and all and my own response to the call to reimagine Christianity ‘the reinterpretation of the symbolic narratives of classical and Christian mythology as a new gospel of human freedom.’

Man, this majorly came up as the grail quest post overlaid my watching of this series ‘ascension keepers’ by William Henry, who sees Jesus as an adept and great initiator much in the vein of Lévi and then says ‘we’re supposed to be trying to put down our baggage and follow him.’ Having also recently aligned with the Christian church in my neighborhood, after rejecting the church as narrow-minded pagan-crushers previously, this feels like really central work for me.

BUT, it seems like the issue is not lack of esoteric symbology to help inner circle seeker type Christians along, it’s that every time these sorts group up they get massacred and/or driven out! Even the mystery teachings which Jesus connected with when he was here, the precursors to the essenes in one reading, there they were using graven images perhaps in various ways in the old wisdom traditions, worshiping some Sophia-like queen of heaven, mother or consort to god the father. Maybe they are making talismans charged with intentions, using relgious art to enter ecstatic states of communion with the divine at their ashara poles in soloman’s temple. Josiah discovers Moses’ lost book of deuteronomy apparently (I’m getting this from sources who see the next events in two entirely different lights but I haven’t done a ton of research) and proceeds no smash every holy thing, to forbid looking at the stars, to burn and then pulverize and then scatter the remains of the ashara divine feminine image from the temple, to then *level the high places so there is no where to put an unapproved altar in the future* and I have seen mountain top removal strip mining so I know the level of violence we are talking about here, then drive out or kill all the elders and priests of this tradition, replacing their old doctrine of community power and freedom in relation to the gods with a book of LAWS.

I go and look up a modern like mega-church type normie Christian leader talking about these events and he calls his talk ‘CLEANING HOUSE’?!?! And makes like ‘yeah bros it just like we have to clean the urge for sin from ourselves and shout out to the single moms out there who are raising godly kids like Josiah cause his dad was bad and then assassinated and then he took the throne at 8 and did this purge when he was like 16’. He did not say ‘wow, this 16 year old was empowered to centralize power by destroying millennia of history of his land’s, his people’s wisdom traditions and he was a traitor and a fool with way too big a hammer.’ The main line accepts that this transition to the law was the historical precedent for the modern tradition and it was good.

I tend to forget this as the first Presbyterian where I’ve been blessed to find fulfilling group practice very near my home is thinking much more deeply about what we are saying and has its heart in the right place. And otherwise I’m on the internet typically getting confirmation-bias in that I’m seeking out and reading other deep thinking seeking types.

So the ‘assignment’ to wonder about why fewer people had taken levi up on reworking the myths of Christianity into a doctrine of freedom pushed me to do some useful work out of my norm. But basically the purge/massacre of the essenes and the cathars follows the pattern: where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in your midst, but get a church on fire with the Holy Spirit for real for real and you will raise the authorities.

J.L.Mc12, you’d have to try it and find out!

Chris, it intrigues me to watch the global intelligentsia remain stuck in the fantasy that Europe is somehow the wave of the future and we (or they) all have to ape whatever delusions of adequacy European upper middle class intellectuals are stuck in. It’s just as common here as on your end of the planet — American liberal upper class intellectuals all fantasize about becoming European in their next incarnations or something, just as their equivalents have since colonial times. Meanwhile the rest of us roll our eyes, recognize that Europe as presently constituted is gasping out the last of a misspent existence, and turn our efforts to our own very different trajectory through history.

AliceEm, I know. As one of the last bishops standing in a Gnostic church, I’ve inherited the legacy of some of the groups that suffered from the pervasive Christian habit of slaughtering anyone who tried to rise above the lowest common denominator of blind belief. How do you deal with the history of a faith that proposes a high ideal of wisdom and love, and then proceeds to express it far too often by way of mass murder? It’s a tangled issue.

@JMG,

Any chance you could give the group a few thoughts and background on some of the practical practices given in the Supplement to the Ritual, especially the Nuctemeron of Apollonius of Tyana which may be the precursor to planetary hours, but using personified virtues instead of planets?

I haven’t made a first read on the country magic and shepherds section yet but it does look interesting.

@JMG,

Even though you mentioned translation issues ( both in the book and during the conversations) is there anything you’d think the group would find interesting concerning your translation project or surprises revealed to you?

AliceEm,

I’m seeing the same thing as I wade through the Gnostic Gospels. The orthodox belief system (the winners who became the Catholics, not the later church) was much more suited to the very hierarchal system they set up. The Gnostics were all over the place.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irenaeus

Irenaeus of Lyons was on the winning side. The article has a decent overview and links to articles about the other side. Why there were so many Christians in Lyons France that early is something I haven’t seen explained yet.

I’d like to build further on the idea I mentioned earlier of the possibility that certain skilled crafts and trades accidentally stumbling towards The Great Arcanum and thus providing a metaphysical energy. This idea provides a possible explanation for the odd cultural shift of the late 1970s, as well as explaining why the digital revolution went unchallenged for as long as it did in the Western World, and why suddenly so many of the institutions and organizations that were being adversely affected by the digital revolution suddenly realized they did not actually like the internet around the middle years of the 2010s. The digital age got started in the 1930s, but for a while it was just ideas floating around. Computers only really took off in the 1940s and 1950s, but there was a lot of opposition in popular culture, politics, and society in general for decades, until this resistance collapsed rather suddenly during the last few years of the 1970s and the early 1980s. The timing here has long seemed odd to me: this was too late to be related to the rise of computers, and too early to be related to mass adoption. Mass adoption of computers only happened well after social attitudes had changed, while the basic possibilites were visible by the 1950s.

This is, however, around the time that computers began to become cheap enough that it made sense for people such as astrologers, and writers to start using them, around the time calculators became viable, and so on. In other words, this is the point in time when computers began to replace skilled crafts on a large scale. If this has the effect of cutting off access to some form of the Great Arcanum, then it follows that this would be the key point in time on the inner planes, and the fact that so much of the cultural shift of those years can be put in terms of a change in the basic understanding of what it means to be human, bringing us towards an image of humans as computers.

The dream of the digital age was still getting charged, because coding is a skilled craft of the kind that can accidentally stumble towards the Great Arcanum, and so with everything else losing charge, the digital age won by default. This lasted until 2014, when advances in AI started to allow people to automate part of the process of creating software, with a rapidly growing percentage of the tasks associated with maintaining computer systems shifting over to these AI systems in the years since. This would have the effect of reducing the number of programmers accidentally stumbling toward the Great Arcanum, and thus reducing the power that they were giving to the dream of the digital future.

The fact that opposition to the digital and the internet went from extremely uncommon and usually considered slightly insane to suddenly quite common in large segments of society during the second half of the 2010s is thus directly related to the rise of AI behind the scenes. The fact that advertisers suddenly started noticing just how much of a mess so much of the internet was, at the same time that the corporate media suddenly got around to noticing that the internet broke their bussiness model, at the same time educators suddenly started having serious discussions about the mess social media and cellphones caused for children and teenagers, and so on through the long list of odd ways that there was a rather sudden cultural shift then is a direct result of the way in which the tech world embraced machine learning during the last decade or so.

On a different note, I have not been able to access dreamwidth enough for it to be useable in more than a day now. Even when I can get it to load, I have not been able to get it to work long enough to sign in and respond to comments/messages. I’m not sure if others are having issues, because it seems the dreamwidth problems have had a very strange geographical distribution to them, but I think it’s worth reporting this issue.

Severo, my son, (after forswearing synthetics for lent) has clearly taken some bad synthetic something and is in a long paranoid state. Please pray to bring him back from this trip mentally strong and clear-headed and with the deep understanding born of experience that synthetic drugs (gummies, vapes, carts all being pushed freely on the youth today) are not worth the risk.

@jmg and silicon guy and also Robert mathessian writing to Clark about Margaret barker in the last grail post, thanks, and following up on interesting references

Hey JMG

I’ll definitely give it a try, seems interesting.

On the subject of the Tarot being used to reinterpret the bible, would I be correct in assuming that you could generalise this and use the tarot for reinterpreting any myth, or at least any western myth?

Hi John Michael,