A little while back I attended an open house at the newly founded What Cheer Writers Club across the river in Providence. Half coworking space, half social center for the busy Rhode Island writing scene, it’s a fine example of the kind of voluntary social institution American society used to be so richly stocked with and needs so badly nowadays, and I’d encourage any of my local readers who happen to be authors, poets, playwrights, journalists, or content creators in other settings to consider checking it out. I spent a pleasant couple of hours there that evening.

While there, I had a conversation with an illustrator, a very good one. He’d attended the prestigious local art school, but went veering away from the normal avant-garde trajectory after one of his classes went to visit the studio of a big name painter (hereafter, BNP) down in New York City. One of the BNP’s many assistants walked the students through the process whereby the BNP produced his art. First the assistants came up with ideas and sketched them out, and the BNP glanced at the sketches and approved them. Next, the assistants prepared canvases the way the BNP liked them, and roughed out the paintings on the canvases. Once the BNP glanced at the canvases and approved them, the assistants then painted the paintings. The BNP then picked up a pen and signed each of the canvases, and away they went to be sold, as the BNP’s work, to rich collectors for jawdropping prices.

The illustrator-to-be was unimpressed by the prospect of going to work in this sort of artistic sweatshop, and even more unimpressed by the way that everyone else treated it as perfectly ordinary. The consequence was that he started asking the questions about art he’d been taught not to ask, and as soon as he graduated he ditched the kind of art that so often these days gets manufactured by the process just outlined, and launched what I suspect will turn out to be an impressive career outside the official art world. We talked about that, and about a number of other things relating to the art world, and one of the things he said has been circling in my mind ever since: “The reason so many people are into abstract art is that it’s impossible to fail.”

Let’s take a moment to unpack what’s being said here. Every artist in every medium has had the experience of having an artwork fail to measure up to the creative vision that inspired it. In that sense, sure, abstract art can fail. Every artist in every medium has also had the experience of having an artwork fail to communicate its creative vision to its audience. In that sense, too, abstract art can fail, and in fact does so far more often than not, though museumgoers are by and large too polite to point this out.

Compare a work of abstract art to a work of representational art, though, and there’s a dimension of risk that the representational artist accepts and the abstract artist shirks. Let’s say you set out to paint someone’s portrait. When you do that, your creative vision is no longer the only thing that matters. You’re not just expressing yourself, you’re expressing something that is not you, and you can succeed at that or you can fail. You can, for example, try to paint a likeness of someone and make something that doesn’t resemble the sitter closely, or at all. You can also paint a likeness of someone’s face that fails to catch any trace of that person’s character and personality and life—the things that a good portrait can express better than any photograph, and a great portrait can express better than a three-volume autobiography. What’s more, if you fail in either way, the failure is something that most people can see at a glance.

That’s the kind of failure from which a purely abstract approach to art protects you. Here as in the rest of life, of course, if you shut yourself off from the risk of failure you shut yourself off just as effectively from the chance of success; there are things you will never accomplish, things that are very much worth doing, if your sole criterion is that you’re not willing to fail.

This same sort of evasion has been taken much further outside the world of the fine arts. I hope no one will mind a reference to one of the subcultures I know best, the subculture of contemporary Druidry. In recent years there’s been a simmering disagreement among Druids about the handling of bardic arts such as poetry and music in Druid practice. Nobody argues that they don’t have a place—quite the contrary, the historic commitment of Druid organizations to the bardic arts, which goes straight back to the earliest days of the 18th-century Druid Revival, is more than matched by the present-day Druid scene.

No, the difference of opinion relates to the role of craft—that is to say, technical skill—among Druids who practice the bardic arts. In recent years, even fairly mild proposals suggesting that the development of craft should be encouraged by Druid organizations have come in for quite a bit of pushback. The substance of the pushback, based on the essays and blog posts I’ve read, is that it’s bad to encourage novice poets and musicians to develop their craft, since the only thing that matters is making them feel good about their creative activities, and talking about technical skill makes them uncomfortable. Therefore they should receive unconditional praise for their creative work, irrespective of its quality, and the huge and challenging issues surrounding the development of skill are casually dismissed on the easy assumption that the novices will pick up some degree of know-how by osmosis as they go.

There’s a lot of this sort of thinking in American alternative spirituality these days. That’s one of the reasons I stopped going to Pagan festivals. Too much of the poetry presented at your common or garden variety Pagan bardic circle can vie for banality and gracelessness with the worst verse in the history of English literature, and let’s not even talk about the droning of badly played guitars, the drummers with a severe case of arrhythmia, and the voices—dear gods, the voices, like cattle trapped belly deep in drying mud!

That is to say, the performers are not the only ones whose interests matter when it comes to the bardic arts. There are also the listeners, who deserve considerably more mercy than they’ve been accorded in recent years. One of the reasons that so many bardic circles are so awful is precisely that people who’ve put in the time and effort to develop technical skill in any art usually end up becoming sensitive enough to its absence that they won’t sit through two or three hours of sustained mediocrity. Think of it as Gresham’s Law of aesthetics: bad art drives out good.

Behind this whole phenomenon, though, is the same flight from risk discussed earlier. To contend with the development of craft in the bardic arts is to wrestle with something that is not you, and thus to run a twofold risk of failure. On the one hand, your poem or your song may be trite and stumbling, or fall into one of the other traps that lie in wait for the poet and composer; on the other, your performance may be clumsy or lifeless or just not quite good enough to reach your audience. You can flee from that risk by insisting that every work and every performance is as good as every other, and refusing to give craft its traditional place in the artist’s life—but if you do that, you pretty much guarantee that you will never be more than mediocre.

This same flight from risk appears all through contemporary life, but I’ve chosen to pick on the arts here, and that’s not simply because the conversation that launched this train of thought was focused on the arts. It’s fair to say that the rigorous, sustained, passionate pursuit of mediocrity is perhaps the most significant trend in the art world today.

The prestigious local art school where my illustrator acquaintance got his degree has an art museum attached to it, and that’s a good place to see that trend in action. For a small museum in a modestly sized east coast city, it’s got some amazing things on display—a huge and vividly crafted wooden statue of Dainichi Nyorai, the Great Sun Buddha of the Japanese esoteric Buddhist traditions, dating from the late Heian period; a fine collection of 18th- and 19th-century landscape paintings; a good assortment of other works from various high points of human cultural history. You have to pass through a gallery or two of modern works to get to the real art, but that’s just one of the things museumgoers generally have to put up with these days.

Before you get to the gallery or two of modern works, though, you pass by the space where temporary and traveling exhibitions have their home. Very often, this contains brand-new works, sometimes by senior students or recent graduates of the art school, sometimes by other artists on what passes for the cutting edge these days. The works on display there by and large have certain things in common. They’re technically crude—it’s rare, for example, to see anything in one of the cutting-edge exhibits that couldn’t have been made by a reasonably enterprising sixth-grader who’d taken a few art classes from the local parks department summer program. They’ve all got artist’s statements couched in a vaguely pompous prose style, so indistinguishable from one another that I’ve wondered more than once if every young artist on the east coast gets theirs ghostwritten by the same middle-aged hack in New York City. Aside from occasional nods to whatever social or political causes might be fashionable at the moment, they’re utterly self-referential, little bubbles of inaccessible meaning cut off from the rest of the cosmos. Oh, and they’re bland. Despite the mandatory parade of edgy iconoclasm, they’re stunningly bland.

All this makes perfect sense if you remember my acquaintance the illustrator and his encounter with the BNP and his artistic sweatshop. In today’s world, the fine arts exist solely for the purpose of manufacturing expensive collectibles for the rich. (The fine arts have always had this as one of their functions, of course; what makes the present distinctive is that currently, that’s their only function.) Thus it’s no surprise that the products of today’s art industry are as formulaic and interchangeable as decorative plates from the Franklin Mint. Nor is it any surprise that the producers of the collectibles in question, while acting out the traditionally edgy and iconoclastic role of artist, are careful to follow some currently fashionably formula to the letter, avoiding anything that might cause their products to be thought unsuitable by collectors, because that way they have some hope of paying off the loans that put them through art school. They cannot afford to fail—but this also means, of course, that they cannot afford to succeed.

Walk past the bland and self-referential collectibles with their bland and self-referential artist’s statements, and come with me to the sixth floor and the statue of Dainichi Nyorai, the Great Sun Buddha. The artist who carved it from great masses of cryptomeria wood didn’t leave an artist’s statement, but then he didn’t need to, as his work speaks powerfully for itself. We don’t know his name, or anything about his biography or his mind. It’s a safe bet, though, that he wasn’t interested in expressing himself. What he was trying to express, and did so magnificently, was the tremendous vision at the heart of Japanese esoteric Buddhism—a vision in which the manifested universe in all its awkwardness and ignorance is itself the play of infinite enlightened mind, symbolized by Dainichi Nyorai. Photos don’t do justice to the result; to sit in the presence of the statue—and the museum has sensibly provided benches to encourage museumgoers to do just that—is to brush against the edge of a serenity as vast as intergalactic space.

Walk past the bland and self-referential collectibles with their bland and self-referential artist’s statements, and come with me to the sixth floor and the statue of Dainichi Nyorai, the Great Sun Buddha. The artist who carved it from great masses of cryptomeria wood didn’t leave an artist’s statement, but then he didn’t need to, as his work speaks powerfully for itself. We don’t know his name, or anything about his biography or his mind. It’s a safe bet, though, that he wasn’t interested in expressing himself. What he was trying to express, and did so magnificently, was the tremendous vision at the heart of Japanese esoteric Buddhism—a vision in which the manifested universe in all its awkwardness and ignorance is itself the play of infinite enlightened mind, symbolized by Dainichi Nyorai. Photos don’t do justice to the result; to sit in the presence of the statue—and the museum has sensibly provided benches to encourage museumgoers to do just that—is to brush against the edge of a serenity as vast as intergalactic space.

The artist who carved the statue of Dainichi Nyorai could have failed, and in fact there are other statues of the Great Sun Buddha that failed, that are trite, formulaic, sentimental, vapid. He, like his less successful peers, was trying to express something that was not himself, and that decision required him, and them, to embrace the inevitable risk of failure. Because he did that, and only because he did that, he was able to succeed.

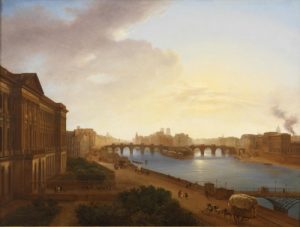

Let’s go down to the fifth floor, and walk into one of the rooms of European art. Here’s a large luminous painting of Paris in morning sunlight as seen from one of the windows of the Louvre. The sun shines down across 19th-century roofs; the Seine flows placidly past; in the middle distance is the little neglected gravel bar where Jacques de Molay, the last grand master of the Templars, was burnt at the stake seven hundred years ago, and the towers of Notre-Dame de Paris rise against the morning sky. Again, photos don’t do justice to the painting; sit in front of it—and the museum has again provided a convenient bench to encourage this—and morning in Paris springs inescapably to life.

Let’s go down to the fifth floor, and walk into one of the rooms of European art. Here’s a large luminous painting of Paris in morning sunlight as seen from one of the windows of the Louvre. The sun shines down across 19th-century roofs; the Seine flows placidly past; in the middle distance is the little neglected gravel bar where Jacques de Molay, the last grand master of the Templars, was burnt at the stake seven hundred years ago, and the towers of Notre-Dame de Paris rise against the morning sky. Again, photos don’t do justice to the painting; sit in front of it—and the museum has again provided a convenient bench to encourage this—and morning in Paris springs inescapably to life.

Unlike the artist who carved the statue of Dainichi Nyorai, Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont, the painter of this vivid and meticulous landscape, is well known to art historians. Her works are found in a great many art museums, her biography can be looked up online, but like that earlier artist, she set out to portray something that was not herself. Failure was always an option; trite, formulaic, sentimental, vapid paintings of Paris can be found by the metric ton; but she took the risk, and so accomplished something that’s powerful and moving in a way that the collectibles downstairs can never be.

I could go on, but I think the point is made. Now it’s time to draw all this together into a shape from which we can go further.

Many years ago, a Seattle architect of Hungarian origins named György Doczi published an intriguing book on form in nature titled The Power of Limits. It’s an extraordinary and richly illustrated work, well worth close study, but one of the most important things in it is a simple passage of text defining a new concept, that of dinergy. Dinergy is the relationship between a force and a resistance that creates form. Think of a grass blade bending in the wind: the wind is the force, the structural integrity of the grass blade provides the resistance, and the result is the exquisite curve that marks the balance between the two.

Many years ago, a Seattle architect of Hungarian origins named György Doczi published an intriguing book on form in nature titled The Power of Limits. It’s an extraordinary and richly illustrated work, well worth close study, but one of the most important things in it is a simple passage of text defining a new concept, that of dinergy. Dinergy is the relationship between a force and a resistance that creates form. Think of a grass blade bending in the wind: the wind is the force, the structural integrity of the grass blade provides the resistance, and the result is the exquisite curve that marks the balance between the two.

Doczi spends much of the book showing the way that the geometries of nature—the shapes of leaves and shells, the proportions of tree branches and animal limbs—unfold from dinergic interactions between force and resistance. He then went on to show that the same thing is true of the products of human art and craft. I’m looking at images of several basketwork hats of the kind traditionally made by Native American peoples along the northwest coast. Their shapes, as Doczi demonstrates, follow classic dinergic lines. Deliberately? Yes, in part—the First Nations in question have richly developed artistic traditions—but there’s another aspect that unfolds naturally from the interplay between the resistance of the cedar bark and beargrass of which the hat is made, and the force exerted by the maker’s skilled hands.

As this suggests, handicrafts made using simple tools or no tools at all tend to follow dinergic patterns, so long as the maker is skilled enough to push the limits of his or her material without going too far. That’s one mode of dinergy as it applies to human creativity. A second mode comes into play when the maker tries to represent something—something experienced with the senses, such as the bear on a Tlingit totem pole or a spring morning from a Paris window, or something experienced the mind, such as the monstrous bird-spirits of the Hamatsa dances of the Kwakiutl people or the infinite enlightened mind of Dainichi Nyorai, it doesn’t matter, so long as it’s something distinct from the artist’s own creative impulse, something the artist can succeed in expressing, or not.

Alternatively, of course, you can flee from dinergy and avoid the risk of failure. All you have to do is refuse the interaction with something that is not you. That’s pervasive in today’s industrial societies, especially but not only here in the United States. Look at the cratered wasteland of our national politics, to cite a very different example, and what do you see? Groups of people who all insist in shrill terms that it’s utterly unreasonable to suggest that they should take into account people who are not them.

You’ve got Democrats braying at the top of their lungs that anyone who questions any of their preferred policies must by definition be an evil racist Nazi, and Republicans who trumpet just as loudly that liberalism is a mental illness. (This in itself marks an ironic shift; not that long ago, it was the Democrats who liked to insist that their opponents needed therapy and the GOP who reliably claimed that their opponents were morally evil.) Listen to both sides trying to claim they won the recent midterm election, and you can hear the terror of failure trembling in every word. Neither side can admit that the other side fought them to a draw, because that admission would force them to deal with the fact that the success of their cause depends on making their case to people who are not them.

It’s the same refusal of dinergy, the same flight from failure, and it produces politics just as ugly and irrelevant as the avant-garde collectibles you can see at the art museum of your choice. As art and politics, so every other aspect of our collective life: the frantic attempt to avoid the risk of failure by refusing to interact with anything you don’t control absolutely is a pervasive pattern in contemporary industrial society. A long time ago, philosopher of history Giambattista Vico pointed out that the arc of history, “the course the nations run,” begins with necessity and ends in madness. The particular shape that madness takes in the present instance isn’t hard to glimpse; what a return to sanity might look like is something we’ll discuss in later posts.

Beautiful and humorous post. I think that the concept of dinergy explains the interesting variation but fundamental similarity found in traditional martial arts around the world, across both cultures and history. Regardless of the time or place, there are only so many ways that a human body can move effectively against another resisting human body, variations in weapons notwithstanding.

Which brings up a somewhat related point: how is the re-working of The Spirit and the Sword coming along? I found the training principles very useful, and got to try some of it out in a recent HEMA tournament in a friendly but spirited series of saber bouts.

JMG, today’s essay hits home for me. In my work as an antiquarian I regularly have to do woth exhibition catalogs of more-or-less abstract art; what most of them have in common is their utter boringness. But there seems to be a bit of a drift back toward representational art.

The phenomena, that bad drives out good, is something which I have also experienced: workshops and other learning events around art, literature and other subjects are often sufficiently geared toward a relatively low common denominator that these things can’t relly hold my interest, or that I can learn much about them, and so there are things that I simply do for myself. And yes, the bland and pompous language, that you describe, is something which I have occasionally seen myself. And do I need to add that publications of current fashionable art often are quite undecipherable (for example, small grey typefaces)?

Dear JMG, Thank you for this post and I cannot agree more. And of course the opposite is also true in that the buyers of these dreary modern works don’t have to worry about failure to appreciate a work either. Having had the misfortune to visit the HQs of several large corporations these offices are often full of the most anodyne artworks (bought I assume as investments and a show of what passes in their minds as ‘culture’). Not having to worry if a representational view of Paris is a masterpiece or tourist trash is presumably a great relief to todays harassed executive or billionaires personal secretary. I also assume this is why works that already have the status of ‘masterpiece’ command such absurdly high prices nowadays. Nobody has to argue about there worth, the ‘experts’ have already done that. All in all a sad state of affairs. Dare I say that a similar lack of aesthetic confidence might be a contributor to the current state of poetry, prose and music in the pagan/druidic scene..?

I hope that bit about bardic mediocrity at poetry wasn’t a slight on that most unrefined genius, William McGonagall. There’s no improving on perfection.

JMG, what is a good example of past politics in the United States of America that more closely resembled dinergic patterns than the politics of our current day?

Good Morning Mr.Greer,

At the beginning of this post you mention that the illustrator in question had “started asking the questions about art he’d been taught not to ask” (3rd paragraph). In this post, you discuss two main themes: the need to practice the technical skills of your craft and to think of failure as a learning experience.What other “questions about art” had the illustrator asked or discovered?

Thank You,

Felix W.

John–

A few random thoughts, hopefully no too far a-field. Politics first, then an anecdote.

With respect to the notion of conformity and the us/them dynamic, it has been interesting to watch the simmering rebellion develop over the pending election for Speaker. I’ve been lurking of late on the old political fora and the shift in the discussion has been notable. In the immediate aftermath of the election, the issue of these freshmen who’d sworn not to support Pelosi was met by and large with a “who cares?” kind of attitude, but as the resistance (!) has crystalized, the rhetoric has become increasingly shrill (“who do they think they are?” and other far less mentionable assessments of their character and intelligence). Several threads have devolved into blistering name-calling by various factions. While I am not of the belief that the rebellion will succeed, I *am* encouraged that it has proven as powerful as it has and the old guard of the party has been forced to deploy more of its strength to contain it. The idea that the newly-elected freshmen might have different notions of how to proceed seems to be confusing to the established powers. Perhaps this push-back is a sign that a much-needed shift in our political dynamics may actually occur at some point?

Secondly, an anecdote (somewhat humorous, in a geeky sort of way) from my own life re flight from failure that was brought to mind by your post:

Many moons ago, I had to stand before my doctoral committee and undergo the oral defense of my dissertation as well as a general oral examination. The latter, of course, had me rather nervous, as it consisted of random questions from the five professors from any topic in the field of industrial engineering that I was to answer on the spot. It was over-all not a bad experience, but I was very jittery nonetheless.

At one point during the questioning, one of the professors pointed to the chalkboard and said “Draw me a concave function.”

It was the simplest of questions, but I was so on edge that I couldn’t tell you at that moment which way was up, much less remember which direction a concave function was oriented. Then, deep in the recesses of my mind, I recalled that the mathematical definitions of convexity and concavity both included the equality (“greater than or equal to” and “less than or equal to”, respectively). So I went to the chalkboard, picked up a piece of chalk, and drew a straight line.

The professor who’d asked the question looked at me, puzzled, then pointed out, “But a linear curve is both concave and convex.”

I looked right back at him, nodded, and said, “Yes. I know.”

I passed my oral exam.

There’s a lot to mull over here, I think.

One thing that I think there is not enough of is the understanding that standards and “inclusion” for lack of a better word, are not mutually exclusive.

My example:

I was fortunate enough to study ballet at an excellent ballet school that understood the difference. There was a professional track for children who could meet the standards, and also an amateur track for people of any age who wanted to study ballet, but who understood that they were doing it as a learning experience for themselves, not as something they would ever achieve mastery in. The tracks were similar in that the same basic technique was taught to both tracks, with the understanding that everyone was to focus and work hard in class to the best of his or her ability, whatever that might be. But a key differences between the two tracks was that the amateur track did not perform. We just studied the technique and learned some combinations in class and tried to get better at ballet, while knowing we would never be professional dancers. It was fun, it was good exercise, and it taught me a lot about ballet that I could not have learned without actually doing (or trying to do). As a result, I can appreciate ballet much better than I otherwise would have. But we in the amateur class did not inflict ourselves on audiences; we knew better, and so did the teacher.

I feel like that is what is missing in a lot of arts education and practice: the fact that having standards does not mean that people who cannot meet them have to be excluded. They just have to understand that they are not good enough at something to do it professionally or to inflict it on others. There’s nothing wrong with failing, as long as you understand that you are failing, and can get better with study, but may never be good enough to move past the “doing it for yourself as a learning experience” phase so that you can better-appreciate the true masters.

If those untalented bards could understand that there is nothing wrong with writing bad poetry and prose, and work at getting better, but do it just as a learning exercise to help them better-understand the art form, without feeling the need to inflict their lack of talent on others, I think everyone would be better off. Ditto for people who lack artistic talent; the art world would be better if they were happy to fail in private, learn from it, and leave professional art to people who can meet professional standards, rather than ditching the standards altogether.

Perhaps it’s our culture’s refusal to let people fail gracefully (and privately), and understand that there is nothing wrong with that – in fact, it’s a wonderful way to learn, just don’t inflict it on others! – that has resulted in this insistence that nobody “fail”, and a resulting loss of all public standards.

@Synthase:

“Along the wires the electric message came:

‘He is not better; he is much the same'”.

Great post John, and reminds me of something I learnt from the OBOD course, we learn wisdom from our failures not our successes. There is massive fear of failure in the modern world, something that I have to learn personally. And I’m glad I have.

Lovely read — thank you for saying what so many will not!

Your thoughts reminded me of a quotation I found a few years back and saved, from Keith Johnstone in his book, Impro:

>We have an idea that art is self-expression — which historically is *weird*. An artist used to be seen as a medium through which something else operated. He was a servant of the God. Maybe a mask-maker would have fasted and prayed for a week before he had a vision of the Mask he was to carve, because no one wanted to see his Mask, they wanted to see the God’s.

Also on this note, Ralph Keyes in his book The Courage to Write asserts that unclear, pompous, supercilious writing arises from a writer’s own mix of fears — including the fear that one has nothing worth saying. Moreover, Keyes points out how many such writers — especially in academia and the literary world — set themselves up with a self-defensive, self-anointing “out”: dismissing anyone who “doesn’t get it” as uncouth, uncultured, missing the “greater” point, and so forth.

Yet as you note with your portrait-painting and poetry examples, quite possibly the trouble lies (gasp!) in the would-be artist’s failure to communicate!

I am currently working toward a Master’s Degree in Middle East Studies and am noticing the same phenomenon. Everything is interpretation now. We barely drill our language skills or learn objective information about our target countries. Instead of learning languages we interpret texts by irrelevant writers. Instead of learning about our countries we make a trite observation about some social phenomenon, bury it in a mountain of theory lingo and call it a paper. We produce texts that are too boring and irrelevant for anyone to read, and I suspect a lot of people prefer it that way. If nobody reads it nobody can criticize you.

Middle Eastern languages and cultures are my passion, but I’m seriously considering quitting and getting a degree in mathematics instead. With maths you always know when you’re failing, and I happen to like it that way.

The disappearance of craft … as a musician, this is exceptionally painful to me. I practice a lot. I don’t want to play with people who don’t. And I don’t want to listen to people who don’t. I take pride in providing music that’s in tune, that sounds clear and beautiful in its tone, that has a tempo both solid and fluid so that those who want to dance can find the beat and dance with it.

Today, there are too many people who think music is something we do for communal purposes only, and I do not agree. It’s not all craft, but unrestrained creativity for creativity’s sake is play. Strumming a few chords on the guitar in your living room beats the heck out of watching TV, but I sure don’t want to have to listen to it.

I heard a band at a nice venue last night in which the guitar player had not tuned his guitar. SMH, as the kids like to say.

OT, get your copy of The Great Crash 1929 and read chapter and verse, the bitcoin bubble is bursting! This will be another test for Trump: if he lets the tech bubble implode w/no assistance, despite shrieks of economists imploring him to do something for “the economy”, we’ll know it’s a whole ‘nother ballgame.

https://smartereum.com/42910/popular-doom-economist-says-bitcoin-bubble-has-busted-is-this-true/

“Interenational Art English” and the existence of online Artist Statement generators is a bit of a rabbit hole, but this is too good not to point out:

https://www.widewalls.ch/artist-statement-generator-500-letters/

I was struck by the drive towards mediocrity ( or, as Yves Smith at NC puts it: the crapification of everything™) at a fine furniture show last week. Most of the work was of very high quality, and there was also an exhibition of furniture by students from two local schools: the Prestigious Local Art School; and the North Bennett Street School in Boston, (which teaches traditional crafts, including cabinet making, bookbinding, violin making and others). The difference between the two was a perfect example of your point: the NBSS students made traditional furniture that looks beautiful and functions well today, and will look beautiful and function well 100 years hence. The PLAS students made chairs that look uncomfortable and are ugly, (although the joinery seemed good) and won’t be around 100 years hence to be judged. At least the PLAS still teaches the furniture students the value of craft.

The experience of your illustrator acquaintance with the BNP brings Warhol to mind: he knew he was selling overpriced crap to the rich, and he named his studio the Factory for exactly that reason.

The joy of doing something well will stay with you forever: I still remember the day, 20 years ago, when I was bringing a boat into dock under the eyes of an experienced pilot. I was new at it, and he fully expected me to clang into the dock. I brought the boat in perfectly and just kissed the dock. Before and since, I have clanged into the dock too hard, jerked the boat around when I should be smooth, run aground where I can see it’s too shallow, and generally failed. The failures are fewer now, though.

Whenever I walk past the sign for the What Cheer Writers Club, I half expect to see you emerge.

@Tom Welsh

Those gems really do have the power to move the soul in directions it does not expect to go, don’t they?

“Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv’ry Tay,

I must now conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay,

That your central girders would not have given way,

At least many sensible men do say,

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses,

At least many sensible men confesses,

For the stronger we our houses do build,

The less chance we have of being killed.”

John, I don’t know if this was your intent but I’m seeing a connection between the modern worlds “flight from failure” and its refusal to accept limits. Also that we can control what is really beyond our control, e.g. that we can control terror by waging a war on terror, or that we can control nature when we separate ourselves from it, objectify it and regard it as a limitless resource we can exploit endlessly. I’m reading a book by Stephen Jenkinson called “Come of Age”, in which he argues that we have a lot of old people but very few elders, a direct result of our culture’s denial of death and its refusal to accept limits. He writes: “…there is something about limit and ending that conjures elderhood from age.” He goes on to say that a culture dedicated to “personal growth” is a culture that “no longer believes in wisdom and ancestry”. Your thoughts?

The concept of dinergy resonates a great deal — like a natural path of growth as opposed to the regimens prescribed by society. It leaves me wondering about those who fall outside the norm and how differently they evolve from those who fit in. Being gay, I often feel like I’m constantly confronted with those who aren’t me, and navigating that experience has definitely forced me to grow in different ways.

I did some art classes online ten years ago or so, when I had it in mind I wanted to become an artist in representational realism (with a dash of fantasy illustration for good measure.) I took classes from two schools, one which took advantage of people who wanted to be artists and the other which was an actual brick-and-mortar art school in a major city with some standards to uphold. Although the curriculum was definitely more advanced at the second school and the instructors more critical, I didn’t find much difference in the students’ progress or, more telling, the students’ attitudes. Everyone in every class was already an “artist” — whether or not they progressed to a degree was more the responsibility of the art school; they just had to show up and submit their work, whatever it was. As you mention with the musicians, I got frustrated with the mediocrity (and the money pit) and went off on my own, only to eventually find the force I was personally working against was a dose of innate dysgraphia I’d never overcome to the extent of being able to draw the way I needed to in order to create what I wanted.

Massive feeling of failure in the end, but the whole experience certainly shaped my growth more than anything I encountered in those art classes.

Knowing most people have at least some personal struggles, I can’t quite believe that our society as a whole has so lowered standards and accepted mediocrity that most people have little to struggle against and therefore little to encourage real growth — I know a great deal of people struggling against a lot of different factors. But they seem to accept the struggle and bend to one extreme or another, instead of trying to grow against those forces and create that lovely bend in the wind.

I have a confession to make: I have failed at playing the saxophone. It took me a long time to get past that special kind of failure where the instrument won’t make a sound. It’s taken me an even longer time to get past the point where if I try to play softly, it doesn’t work. Sometimes I still fail to play the right note. I keep playing though: it’s called practice.

I wonder how much of the mediocrity of life around us is related to the utter unwillingness to practice anything that so many people seem to have these days.

I think you’ve also touched on one of the key weaknesses of Faustian culture: it’s not just our shape of time that can’t handle failure: it’s hardwired into our entire culture. Faustian humanity has none of the usual tools available for handling failure, since it’s one of the key aspects of human existence we deny. Is it any wonder then that we run screaming from anything that reminds us that it exists?

Hi JMG, I have mentioned to you the issues I see, here, working at the “war factory” that are in line with your posts and “Twilight’s Last Gleaming.” I see the flight from failure everyday in inaction, delegation, and finger pointing, and most often, nothing gets done.. Heading down hill quickly.

Thanks for another good essay,

Mac

Bnp=julian shnable

Are you familiar with John Minahand’s book on the filid of Ireland, The Christian Druids? Their dedication to the poetic craft was rather intimidating, although I’m not sure if many of their stylistic conventions would be worth resurrecting…

@El: Absolutely agreed. And I would furthermore note that everyone learns at their own pace, and some people just aren’t interested in hitting the “right” milestones.

One of the reasons I haven’t gotten back into martial arts, for instance, is that both classes I went to regularly seemed to take it as read that of course we all wanted to be black belts and teachers, of course we all wanted to get there in a certain time limit, and we thus wanted to be ready for tests at regular intervals–and I didn’t, and wasn’t. I’d have been happy practicing front kicks for years. (See also: tournaments.) Likewise, I’ve had friends who stopped taking voice lessons because they just wanted to sing well enough for karaoke and Christmas carols, and the instructor didn’t know how to teach without aiming at operatic solos.

(Fanfic gets a lot of flak for being “not real writing” along similar lines, and I think the people complaining really miss the point: most people in that field are hobbyists of a particular sort, and almost none of them are looking to go pro.)

The tricky part comes with “inflicting it on audiences,” granted: for example, where cooking is concerned, my dad is not a professional chef, but he can and does cook for company, whereas I enjoy cooking and baking, but my skills (and, honestly, my taste–I like things a lot sweeter and a lot blander than most people I know) are really not up to a fancy dinner for guests. (You come over to my place and, unless you like scrambled eggs or spaghetti a lot, we’re ordering out.) So there’s a grey area.

I think that area is one a lot of laypeople occupy with regard to politics, too. There are definitely some mainstream-ish opinions whose holders I don’t want to be close to, and whose well-being I don’t particularly care about (other than a vague notion that society should look after everyone to a certain extent), but I can have a relationship of businesslike and/or familial civility with them when I have to, and I frequently have to. (Goes for interpersonal relationships in general, too. One of the best pieces of advice I ever got was “You don’t have to like your friends’ friends.”)

@JMG: “Too much of the poetry presented at your common or garden variety Pagan bardic circle can vie for banality and gracelessness with the worst verse in the history of English literature,”

Ugh, so true. Pagan poetry (I do not recommend that any of my fellow English majors ever search for spells/incantations on Google–it’s a fetid swamp of twee passive voice and sentence mangling that would put the rack to shame) vies with fantasy poetry (including a fair amount in books published by major houses) for the top example of Sturgeon’s law in action–at least in my experience. I’m told that Christian rock/lit stuff is even worse*, but mostly I haven’t had the nerve to look.

My general maxim re: art is that, when intention/message gets prioritized over technique, the results are going to be mediocre at best.

* Though actual hymns, as I think we discussed, are fine–as long as everyone knows how to sing them. The tiny local church here in PA, sadly, combines a total lack of baritones and an extremely decrepit organ with a strange enthusiasm for hymns nobody’s ever heard of. The result resembles a drawer full of crickets more than anything else.

It’s past midnight here in Beijing, so this is going to be a bit scattered. Still, I’m fascinated that you wrote this, since it’s been on my mind a lot recently.

One of my lifetime-favourite authors has been Rosemary Sutcliffe, whose books I first read in primary school, and which I still enjoy today, forty years later. Her best-known sequence of novels follows different generations of a Roman military family through the centuries when they live in the province of Britannia. It begins with Rome in her prime, an ascendant empire only recently arrived in Britain. It ends with the Arthurian period; the legions have left, the island’s cities are semi-derelict, and the shores are under furious assault from the building Saxon invasion. The remaining elites – educated Romano-Britons who still identify with Rome and her culture, allied with the remnants of the pre-Roman Celtic tribal aristocracy, refer to themselves as “lantern-bearers”; they know they have lost much, maybe most, of what their forefathers knew, but they dedicate themselves to preserving what they can for their descendants, hoping that their culture will flourish again one day.

In terms of Druidry, I rather think we are midway on that journey. It’s a problem I have with the OBOD course, which refers to the 20 years’ education of the classical Druidic colleges, and breezily reassures us that our contemporary education covers most of it anyway… except that it doesn’t. Readers of your blogs know that our education today is unfit for any purpose; through TADR, I discovered the Trivium and Quadrivium, and was appalled by how much higher the standard of education was in the past in my own case – and, truthfully, I had an exceptionally good education compared to many in the UK. A recent gwers told me not to worry, that we couldn’t be expected to remember everything we were taught: but we know that memory was the foundation of druidical education.

In short, we today cannot, in almost any case, approach the educational standard of the old druids. The very best we can do is, in humility, to try to preserve the tools that have come down to us, to strive to master them as best we can, and to pass them on to the next generation in the hope that they will surpass us. To tell ourselves that all effort is good, and none better than others, is to betray both the past and the future; we have an obligation to attempt excellence. Some will succeed, and some will fail, and all need to acknowledge the difference.

Here, of course, you have firmly entered Jordan B. Peterson territory. I know you say that you don’t read him, but one of his key maxims is that hierarchy is both natural and desirable, because in any and every field of endeavour, some people will be better than others, and that this needs to be acknowledged.

This is part of what drives the fury against Peterson: it’s the rage of those who cannot bear to be told that they aren’t special, or outstanding – that they are, in fact, mediocre. Once upon a time, our society had value structures that allowed people to deal with this, and which prompted them to strive to be better. One challenge that Green Wizards, and Druids, and anyone else concerned for the future, needs to be doing is contemplating how such structures can be re-established, and soon. I propose that this is one area where contemporary Russia – but not China – is succeeding, and that this is another reason why the elites of the Anglosphere are raging so vehemently against a culture which accepts that life has losers as well as winners.

I’ve always followed what I call the Unwritten Law of the Art Museum – the bigger the write up regarding a work, the worse the work is.

Small essay this week with huge implications. Thank you.

To your point, I think the fear of failure endemic today is related to the lack of practiced craft among most people. In earlier times or poorer places most worked at least some times on projects that gave clear and often immediate feedback: mending clothes and maintaining roofs, cooking and entertaining for friends and family, managing small enterprises, almost everything we used to do either took dinergic forms, or failed right there in our face and in front of the world.

Failure is our greatest teacher, and learning to manage and harness it used to be an integral part of becoming a healthy adult. Not so much anymore, especially among the elite. The emotional fragility and pervasive unhappiness that’s shot through our civil society right now looks due in large part to this.

Every kid should learn to do well something difficult that others judge honestly and publicly. Barring physical injury, private failure is a poor teacher.

Is this a divergence from the “sobornost” vs. “tamanous” posts? If so, are we going to pick back up on that, or is that done like the post on education back on the ADR?

Interesting! I’ve failed many times in every medium I’ve been involved in. I’ve failed at making music, at acting, as a playwright, as a draughtsman, as a photographer, as a short story writer, screenwriter and as an essayist. I’ve made so, so much bad art, mountains of bad art that so earnestly failed, some of it quite publicly! And with some mediums I feel I have made some qualified successes, and they have felt real to me because failure is always an option.

Reading Hesiod’s lovely Theogony, he makes the point early that the Muses gave him the divine voice from which he sang. Point being that he served as a vessel to the goddesses. The inspiration in no way was his. Whenever I’ve really gotten into a piece of art that has succeeded, I felt I was carried by something outside of myself. Indeed, it can be a mystic experience, and Evelyn Underhill points out the similarities between the mystic and artistic temperaments many times in her books.

Perhaps the rigors of practice, of study and of refinement could be conceived as of the making of the vessel; being sure there are no holes and the shape is correct to receive the divine flow of inspiration from the Muse.

I wonder if this is part and parcel of the fashionable insistence the people should be “nonjudgmental”–that no one should ever judge anyone or anything. I’ve often been on the receiving end of a tirade when I calmly tell people that, no, I’m not “nonjudgmental”, that I think it is impossible for one to be “nonjudgmental” and conscious at the same time, that you may judge things differently and have different values than I do (and that’s okay), but that’s not being “nonjudgmental” which is, again, impossible (to have a functioning mind and be “nonjudgmental” at the same time.) I guess it’s b/c I don’t validate their virtue signaling that I get on the receiving end of the tirade, but I simply will not tolerate this “nonjudgmental” about face and foolishness. It is so liberating to allow yourself to judge and to judge freely and w/out reservation. I often tell the “judgement police” that my judgments only matter so much as they give credence to them, and I’m more than willing to let them disregard my judgments so long as they allow me to disregard theirs in kind.

Wonderful post, Mr. Greer!!

We don’t treat our artists of any stripe very well; it’s almost impossible to make a living in the arts, unless you teach. But for those who taste the water, and find it irresistible, art holds them for life. Art circumvented in one field will crop up in another. For me, the other was Music, and after 65 years of picking it up and putting it down but never forsaking it, Guitar and Voice have become old and patient friends, faithful mirrors, and demanding in terms of technical prowess.

The musician (any artist) faces this truth; The more you play, the better you get and before you know it, you have become a Music (Art, Lit, etc) Snob, eh? in that you recognize excellence and are only just tolerant of trite and predictable execution. Of course, in the long view, the looong view, we’re all beginners, so the teacher mind becomes involved with those who actually want to pursue the craft more than they want to display for everyone. Anyone who pursues a craft knows that thousands of hours go into mastering it, and almost all of those hours are private. When a craft of any kind is honed to that level of technical skill, it is a worthy medium for the revelation of content; expression, emotion, tapping the universality of understanding. To hone craft and yet retain spontaneity of presentation and depth of maturity, this is mastery.

Thanks again, JMG!

The fear of failure as a phenomenon in our society is widespread as you say, and the fine arts example is the tip of the iceberg. The education system feeds it (and then feeds off it at the higher end) with the focus on standardized testing which can only measure things which are “right” or “wrong.” The schools that don’t test well are labeled as “failing,” and are largely full of students from poor families, which reflects our collective fear that poverty (otherwise known as failure) might be contagious.

Thus what you’ve written largely makes sense and seems worth reflection to me, with one minor quibble. Describing the recent election as a “draw” seems a bit of a stretch. On one side you’ve got a net gain of 2 senate seats (which is not nothing, of course, but the Republican party couldn’t have asked for a more favorable set of contested seats), while on the other there’s a net gain of 38 house seats and control of the legislature, 7 governorships, over 350 state legislative seats, and a net gain of control in 5 or 6 state legislatures. Granted, it’s certainly not the Blue Wave ™ that was bandied about in the media, but it looks a little lopsided to be a draw.

Still, it’s your living room, and I’m curious to see where you take the discussion of our society possibly returning to sanity from the current madness. Thanks for the food for thought, and a Happy Thanksgiving to you and all of the other US readers and commenters.

One thing that really sets off the “nonjudgmental” set is when I tell them that, IMHO, “nonjudgmental” people, more often than not, are doing things that go against their conscience, that they know in their heart of hearts to be wrong, according to their values, and that when others notice that and point it out to them, it rubs them raw and they go off on a “nonjudgmental, who are you to judge?!” tirade. Who am I to judge? A person who judges w/every breath in and out, just like every other living person.

so the “everyone gets a trophy” principle has been adopted by druidry? i guess i shouldn’t be surprised. one question though: my understanding is that the bardic tradition originated in the era before widespread literacy. the bard was therefore the repository of the oral history and culture of the people, making a good voice and poetic sense secondary to a prodigious memory. are today’s druid bards the inheritors of that oral tradition or merely modern equivalents of the bad bob dylan clones of my youth?

@ Bogatyr

If you don’t mind, what is the name of that sequence of novels you mentioned (Roman to Arthurian Britain)? I’d be interested in hunting those down.

@ Shane

Re judgement

What many fail to distinguish properly, I’d argue, is the difference between judgement (which, as you point out, everyone does by virtue of being sentient) and respect. I can disagree with you, judge something according to the values I hold, and yet be polite and respectful. Not all judgement is rude. I can say, “I don’t care for that” or “that stance goes against my values” while being respectful to others’ assessments. People who insist that *any* judgement (that is, disagreement) is inherently wrong are, to my mind, peddling a worldview of enforced conformity.

I just want to make the obvious point in the modern west, very especially America, “loser” is the fundamental insult.

Interesting essay. The bit about the big name painter was an eye-opener to me. Having an assistant paint the finer details of a lace ruff — okay. Having him paint the whole thing — not okay.

Doczi’s “The Power of Limits” appears to follow in the footsteps of an earlier work by D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson, “On Growth and Form”, which explored patterns in nature, and growing things, and much else besides.

Which makes me think. These two books are anchored in nature. Classical art, and some modern art like my favourite Impressionists, is anchored in nature. But abstract art has no anchor. Perhaps politics based on an abstract ideology is anchor-less, compared with politics which responds to the hopes and fears of flesh-and-blood people.

John–

Okay, I’m afraid this may be coming from far left field (as in beyond the fence-line and well over the horizon), but how do the contending forces of dinergy which create form — which I immediately link as well to Ring-Cosmos and Ring-Chaos in their interaction with one another — relate to the contending forces of Thaumiel (or not)? What got me going down this particular rabbit-hole was the pondering of the perpetual political contest — there will always be an opposition and therefore “both sides” will suffer from perpetual frustration, much as the two rings dynamically interact with one another and cannot exist in the absence of the other — and I thought to myself, how does this differ from the nature of Thaumiel? Do the Qliphoth denote some degree of truth in terms of the nature of things?

I like that dinergy bit, and it figures well to make sense of my experiences. I am going to give some cases.

I am a (more or less deliberately) decidedly mediocre player of the two chamber North American flute. Check it, I figured about a decade ago that I would do well to have some music experience in my life, but I also knew that I only wanted to put a modest amount of energy in that direction. So I chose to play an instrument that had an intentionally limited variety of sounds, and which makes pleasant sounds with modest skill. Hence the native flute, 6 notes built around a pentatonic scale, and a hand full of ornamentation techniques to spice it up. Because it works with such a limited pallet the early swing of the learning curve is pretty sweet. That being said, I am a mediocre player, because beyond learning a handful of basic ornamentations and a small handful of songs, I haven’t accepted the limits of the musical craft other than those that the physical nature of the resonance chamber imposes. It sounds pleasant and on a good handful of occasions I have stumbled into performing a bit of music which, by the accounts I receive, really touched a person in a positive way; most vivid cases being from some homeless veterans I used to jam with who found the flute soothing. At the same time, I cannot reliably produce even decent music, and as often as not I go to play and the just ain’t any spark or jingle in the tune; a true master of the instrument can call forth a sublime serenity with overwhelming effect, that my efforts only occasionally touch on the lower range of. More practice would help, so would learning a little more craft… maybe getting a couple more classic songs dialed in. I cannot fail or succeed at playing my own little free styles, but I can very much succeed or fail playing House of the Rising Sun. But, at the same time I am only slightly interested in being more than a dabbler in music, fairly content to accept the resistance in my own life and the form it gives when acted upon my the mostest force of my desire to make music.

Farming, is also a place where the will to mastery meets the resistance of life, and in that case gives me the shape of a specialist. Long story short, I have found that the various things I will in life do not fine well with the restrictions of owning or running a farm. But by accepting those limits, and then directing my energy along the path of least resistance, I now have an arbitrary supply of work as a helper / advisor for other successful organic market farms in my area. Allowing me to to work more diversified that I could ever successfully manage by my own hand, and to profit from the superior business craft of my clients who run their market gardens.

Poetry is another domain where this dynamic meets, but in my experience it is two forces that resist and swirl around each other, then tied together by a third and harder to name thread. I like the kind of poetry currently approaching the maturity of it developmental form in lyrical rap. Now I ain’t a rapper, but I like playing with the form in casual poetry. Those two forces I am on about are on one hand the many poetic tools of various kinda or rhyme, pun, and meter one can bring in and on the other the vision to tell a story. These forces limit each other, the first force demands the story be told creatively, to use pattern of rhyme that are fixed realities in the English language; the second force limits the effort to weave sophisticated rhyme schemes by the need to convey a certain amount of content. This art form is modestly young and the craft is still evolving quickly.

A sidenote: artistic sweatshops are nothing new under the sun: e.g. Cranach the Elder and Rembrandt come to mind.

The art museums and mainstream publications are just catching up to the resurgence of representational art that’s been developing for several decades as a movement dubbed Pop-Surrealism. The “godfather” of the movement is painter, Mark Ryden. If you’re not familiar he’s worth a search, I think you’d be impressed by his craftsmanship and amused by his symbolism.

Btw, yesterday I enjoyed your latest podcast with The Higherside Chats. I had to fanboy out and become a member to hear the whole conversation. Taking notes. Thx!

One craft about which I do know something is quilting and I regret to have to say that we have passed Peak Quilting at least a decade ago. I see two influences at work here; cost and status.

The revival of this wonderful craft began in about the early to mid-70s, when older practitioners were still alive and every town had a fabric store. Innovations in technique–rotary cutting–were not at first as corrupting of good workmanship as they later became. Much good work was done in the research, reviving and recreation of historic piecing and quilting patterns, and for several decades the standard of workmanship in most quilt shows remained very high. Then came the free arm quilting machine, which inscribes an ugly pattern of squiggles all over your carefully constructed quilt top; it was Fast, it was Easy and it made and makes a lot of money for quilt shop owners.

Meanwhile, cost of fabric and tools has risen dramatically as has the social status of quilters, and the quality of design AND workmanship has declined equally dramatically, IMHO.

I’m convinced the persistence of abstract or conceptual art is due to the fact it places the critics, collectors, and elite socialite types at the centre of the process and not the artists. An artist creates some vague art assemblage and then the intelligencia get to swoop in and determine it’s meaning, importance and value.

With no standards or craft to ground the work the level of quality can be whatever the gatekeepers claim it to be. It’s like looking at a Rorschach test and insisting your interpretation is the correct one.

Much to do about nothing.

Makes me think of a intense and highly passionate conversation about peoples Christmas plans I overheard the other day. One couple were very intensely describing the abstract Christmas they were going to have. This went on for a insane length of time followed by a discussion about a recent art purchase of a BNA. It was a crumpled peace of paper that went for several thousand.

My partners a composer, the examples are endless there as well. I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s not worth thinking about this level of retardation. It becomes like disaster porn. At some point we need to stop looking as it’s too much of a distraction from the real work that needs to be done. BNP or BNA, why not? If someone else is going burn money let them. Good hussle if you can find it imho.

Hi Everyone,

I have seen the result of this sort of thing in university theatre. Quite a few of the plays are excruciating despite the lovely and talented young actors because the Profs pick plays they like and they are dogs. The Profs don’t have to worry about bums on seats. They are paid no matter who turns up.

The youngsters graduate and what saves more than a few of them is an insistence on acting in the theatre of the real world; the Fringe Festivals and the local theatre where the audience is directly critical. The Fringe performers rely on word of mouth advertising to make their show profitable. This means they can and have to change scenes up, do drastic rewrites, work with the lighting and other effects until they have the audience loving their performance. This is the way all the great actors and playwrights learned their craft.

The same is true in the world of journalism. The universities produce journalism graduates who cannot write intelligible prose and have never seen a style guide, I kid you not! Old lags in the journalism world say journalism can no more be taught in school than lovemaking (that is not the word they use) can. They insist journalism can only be learned under the lash of a sub-editor and I am inclined to agree despite not enjoying the violently insane editor of my youth.

Wonderful article.

PS Druid magic has opened up my interest in and pleasure of creating representational art.

Maxine

I am minded of an excellent art teacher of my acquaintance. What makes her an excellent teacher, is her ability to teach students who have no particular aptitude. How she does it is the very opposite of praising mediocrity, but rather she teaches the techniques and disciplines of craft.

I saw this at work in one of my sons, who would be gifted in the bookish sense, but whose relationship with art in primary school was one of profound dissatisfaction. Many days included assignments that went “here are some crayons, draw a picture of this or that, oh yes that’s wonderful” – but the “that’s wonderful” part just grated with him, because he knew there was such a huge gulf between what his mind saw and what his hand produced.

Enter his secondary school art teacher. At the start of his first year his class did six week “tasters” with all the subjects, before deciding on the ones to stick with. I know that if she had not engaged his attention in those six weeks, he would not have stuck with the subject of art. But one day, during the “taster”, he came home and showed me the shading technique she had showed them that would turn a 2-d circle into a 3-d sphere. I could see the excitement in him (almost a TSW moment!).

That got him interested and he stuck with three years of very hard work at perfecting the craft of art. I would say that, as a child with no special aptitude for art, that class was the one he worked at the hardest throughout any part of his schooling. There were drawing exercises that he had to do every single school day throughout those three years. And he did them, and ultimately gained a quiet satisfaction when he could see his own improvements.

The end of this story is that he did not become an artist. It’s possible he may never touch another drawing pen or paintbrush. But he still remembers an art teacher who succeeded in drawing out of him, a student with little natural aptitude or talent, a yearning for excellence, and a dedication to working at the crafting of art. To me, that is a real sign of excellence in a teacher, because teaching a student who already has aptitude and talent is not nearly as challenging. To him also, she still rates as one of his very best teachers.

Anyway, this story is by way of adding a wrinkle to the “can’t fail them” ideology. The fact is that it is hard to fool yourself as to whether you have succeeded or failed at what you set out to do, even if your teachers and other authority figures are conspiring to hide that hard truth from you.

Thanks JMG for another look at modern culture through a different lens.

As I was reading this, I began to wonder whether another factor besides fear of failure might be driving the observed lack of quality.

I would agree that art, music composition, fine woodworking, literature – “the arts” – reached a peak in quality in the 1600s-1800s and have been declining ever since. Similarly, it seems that automobiles reached a peak around 1950-1980 and computer technology reached a peak around 2000-2010, and both have been declining in objective indices of quality (i.e. user experience and longevity) since those peaks. At the same time, I would argue that there has been no observable decline in the quality of top athletes, chefs, and musicians. If anything, thanks to a global playing field and a growing population, the level of performance and commitment to craft at the top has gone up a bit.

The difference here, to my mind, is that live performers are always compared in the present – we can’t compare a meal prepared by a top French chef to one from the 1700s – whereas durable products and works of art are easily compared to the past. I might make a case that a loss of quality arises not so much from fear of failure but from commitment to the myth of progress, the idea that what is new (and endorsed by the right influential people) must also be better. As a field or technology is developing, changes are most often improvements, but once it becomes mature and subject to diminishing returns, our commitment to progress dictates that we must not be satisfied with a stable state of the art but must instead pursue dramatic “new and improved” changes, which more often than not push the pendulum away from objective quality.

I teach woodworking. My client/student wants to build a 16″ x 20″ wet plate camera from wood. I have no experience building cameras. She has no experience in woodworking. We have a few examples of smaller format cameras from the late 19th and early 20th century. They’re well built, but don’t scale up. Because of budgetary constraints we can’t afford to use complicated mechanisms like rack and pinion gears. Neither of us are machinists. It has to be inexpensive, simple, rugged, and it has to work. It also has to succeed as an object of craft. The fit and finish of all the pieces must be spot on or it will look ridiculous and amateurish. The operation must be smooth and direct. I’m still not exactly sure how we’re going to do this.

“n which he argues that we have a lot of old people but very few elders, a direct result of our culture’s denial of death and its refusal to accept limits.”

The Greatest Generation was the last generation to fully mature to adulthood, and I felt the loss profoundly w/their passing, knowing that there were no adults left, only children.

Mr Greer,

Well thanks so much for the humorous screed on modern art. Most enjoyable and unfortunately so true. As a retired Artist (that is, one who does it for the money) I have long recognized the veracity of a couple of maxims common to the art industry. Namely; There is art, stuff that looks like art and garbage. If you cannot produce art, make what you do very big. If you cannot do it big, make it red. Yeah, I know, it’s a cynical view, but some 40 years in the game has had a twisting effect on me.

Now that I no longer engage in the mind numbing pursuit of money I can happily call myself an artist (no longer capitalized). It’s quite delightful to paint representational images, portraits mostly, with no thought as to whether they will sell. I just finished a portrait of a recently deceased friend as a gift for his family. It’s actually the only piece I have done since retiring that has left my immediate possession. Believe me when I say this is something for which I am truly grateful. I cannot tell you how many people have told me I could easily sell what I do. To not have to do so is a real blessing.

For those who would paint or sculpt well, in a classical sense that is, all I can say is it’s a lot of work. I attended art school in the mid 60s just as some of the changes were taking place. As a youngster I loved my avant-garde professors and could not stand the old schoolers. Darn, that has so changed. While I can recall no wisdom from the with-it profs, I still use and revere the teachings of the classical teachers. I particularly remember a class (several over the years, actually) by an older professor (name long forgotten) who taught life drawing. He came to class in a tan smock and used a metal pointer to emphasize the things he thought important in drawing the body in a realistic and believable manner. I can still see the wince on the faces of the models as he would poke a fleshy place to demonstrate the way light and shadow defined form. (The wince came from the fact that the pointer was cold.) His approach was so measured and steeped in doing it well that at the time I just was beside myself with impatience. But his teachings have served me far, far better as a professional than any others I encountered in that venue.

I approach a painting now much like you recommend when discussing the task of writing. First, it’s a daily process. For a new painting, I get it down right away, without the editing. It’s all about the structure, the ideas, the big picture (pun unintended but enjoyed). Then it’s time to edit. Keep in mind that a period of rest can be essential to the editing process too. Sometimes I literally cannot see what I have painted until I have set the canvas face to the wall for a few weeks or even a few months. And then I edit and edit and edit again. I’m going to lift an idea (possibly verbatim) from Jordan Peterson where he describes his writing process; I’ll say that when I get to the point where further editing, further changes, do not improve the image, I am done. It’s not perfect but it’s as good as I am capable of doing at this time. I am at the very limit of my ability.

I have been asked by people who have seen my work how I manage to capture so much of the character of my subjects. I honestly don’t know. It just seems to happen. I paint what is in front of me. The character is there all along. The magic for me is being the agent of transfer from real life to a piece of canvas. It’s called creativity but I think that is just a shorthand word for something much more enigmatic. (Kudos to whoever said, up thread, that we are just channeling the divine.) Even back in my art-for-money days I would thoroughly define the limits of what I wanted to do and then take a break from thinking further about it. Usually within a couple of weeks the answer to an artistic problem (project) would pop up all by itself. I irreverently called it the lazy man’s way to creativity.

By the way, your words about the young illustrator brought to mind the work of Simon Stalenhag. He’s a young artist and I find his work quite refreshing. For an example of his work take a peek at his book: The Electric State. Easy to search for him online.

My heartfelt thanks and very best wishes to you and to all who bring so much refined thought and insight to these pages.

Aged Spirit

There must be something deeper going on than the “refusal of dinergy” by an awful lot of people. We as a civilization seem no longer capable of profound artistic expression. Even those who attempt to make “honest” art more often than not turn out something derivative or simply mediocre. For example, in classical music, the fad for atonal and highly experimental music has long since passed and there are plenty of neo-romantic, neo-classical, neo-whatever-you-want composers plying their trade these days. But very few (if any) are really doing anything interesting. Very little of it will be heard in concert halls in fifty years, let alone two hundred.

By the way, didn’t Spengler predict this as a consequence of entering the “winter” phase of decline? In any case, I can’t quite understand why it has all dried up. There are more art schools than ever, more wealth and comfort (theoretically conducive to making a better product), more exposure to other ideas, more tools, a much more egalitarian society (meaning more opportunities for more people to study art) — and yet so little quality. This is a cliched question, but why can’t we produce a Mozart?

@David,

an extension of that is everyone’s oversensitivity. Everyone needs everyone else’s approval for what they are doing, otherwise: meltdown. To the “nonjudgmental”: why do you need my approval for what you are doing? Why should my judgment matter one whit as to what you do, unless you care about it? I certainly don’t care about others approval of what I do, and it doesn’t affect my choices unless I value their opinion.

The opposite of dinergy i guess is the wildly popular corporate buzzword ‘synergy’ which implies a merging together to achieve a mass – multiplier effect, as opposed to the delicate dance of the dinergy which you outline here. Am reading Teilhard de Chardins ‘Future of Man’ at the moment, where he saw the comng Anthroposcene as a dinergestic unfolding of a developing ‘universe’, in the form of the collective and spiritual impulse ,striving to itself become reflectively conscious in tandem with Gods will. This got me thinking we may have counterfeit this impulse with the internet and the culture of insitutionalised narcissism currently du jour. Chardin was coming at this from the perspective of a Jesuit holy man, i am surprised they didnt burn him at the stake. He is often portrayed as the grandaddy of the internet.

Google ‘synergy’ and what comes up is a plethora of corporations striving to be identified with the term, which gives one a clue as to the inner nature of the corporate ethos.

Besides abstraction, some people also refuse to engage with “not them” by taking an avant garde approach to something pedestrian. I’m thinking of artisinal food such as pizza or burgers. It’s true that a burger or a pizza are not abstractions, but by taking the artisinal approach there is also a certain isolation from failure. If I don’t happen to like the toppings on my artisinal pizza it’s not a failure on the part of the chef. It’s simply that I fail to share his vision of what a pizza should be. The same is true if I don’t like the exotic cheese on my chesseburger. Left unsiad, probably, but obvious to all parties, is that I may be too plebeian to appreciate his masterpiece and maybe I’d be happier at Micky D’s. I have more respect for the few remaining Mom and Pop burger joints that make an honest, but simple, burger. They could fail in a way that the avant garde chef can’t. At the same time they rise above the mediocrity of the fast food chains.

I’m not suggesting that all avant garde efforts (food or anything else) can’t be good. I’m just suggesting thaat by doing something highly unique the artist/chef/architect is avoiding engagement with “not them” and thus saving themselves from the possibility of failure. At least sometimes, this is what’s going on. They’re kind of running away from the problem in the opposite direction, but ending up in the same place.

@Will J – I think you are on to something; lack of practice is as much to blame as the notion that some people ‘will just never be good artists.” Sure, there are some people who can’t carry a tune in a bucket, but there are other’s who have flashes of talent that, I suspect, never take the time to get better.